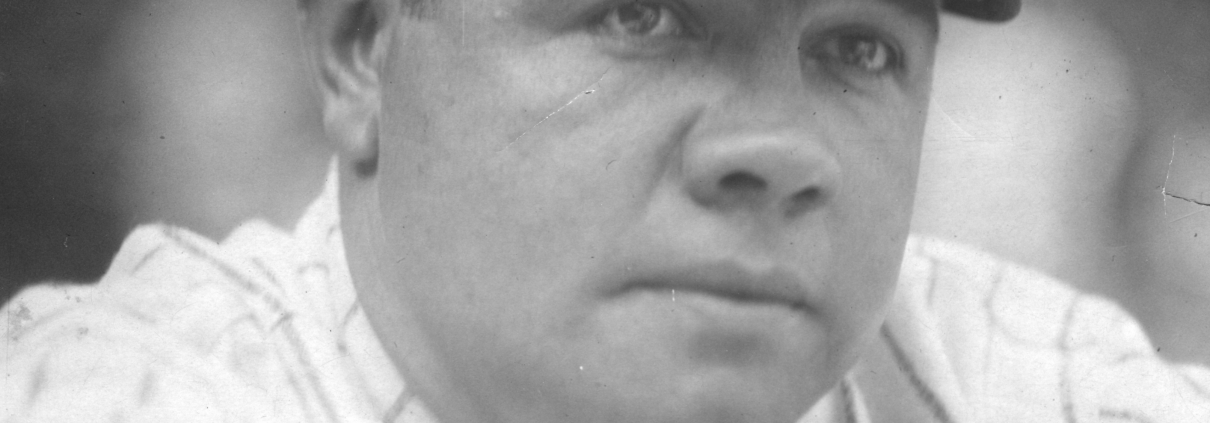

July 19, 1920: Babe Ruth breaks his own record with 30th home run

With two months left in the 1920 season, the New York Yankees and the Chicago White Sox were both in the thick of the American League pennant race. The Yankees began the day in second place, 1½ games behind the front-running Cleveland Indians. The defending AL champion White Sox lurked in third place, 5½ games off the pace.

With two months left in the 1920 season, the New York Yankees and the Chicago White Sox were both in the thick of the American League pennant race. The Yankees began the day in second place, 1½ games behind the front-running Cleveland Indians. The defending AL champion White Sox lurked in third place, 5½ games off the pace.

The Yankees and White Sox were in the middle of a six-game series on Monday, July 19. The series included two doubleheaders on July 19 and 20 to make up for weather postponements during Chicago’s previous visit to New York in May. The Yankees had taken the first two games of the series over the weekend, but the bigger story was that Babe Ruth had not hit any home runs, his last circuit clout having come against the Browns’ Bill Burwell on July 15.

The Monday doubleheader between the Yankees and White Sox attracted a packed house to the Polo Grounds,1 although the pennant race was a secondary concern to many of the fans. The “two games were mere incidents. They were waiting for the breaking of the world’s record, so they could say that they were there when the Colossus of Swat swung and hid the achievements of the Ansons, the Delahantys, the Brouthers[es], the Freemans and all the others further in the dim mists.”2

The Yankee faithful had some anxious moments prior to the game when a localized burst of rain showers struck northern Manhattan about a half-hour before the scheduled 1:30 P.M. starting time, and it appeared that the two teams might be able to squeeze in only a single contest that afternoon. After assessing the state of the grounds, Yankees manager Miller Huggins determined that the doubleheader could begin at 2:00 P.M.

The Yankees won the first game, 8-2, behind the stellar pitching of Bob Shawkey, who made his first start since suffering an injury in St. Louis on June 23. Ruth, however, disappointed the crowd by failing to homer in the Yankees victory.

In the second game, the Yankees sent left-hander Herb Thormahlen to the mound to oppose the White Sox’ diminutive southpaw Dickey Kerr. The throng at the Polo Grounds was again frustrated as Kerr walked Ruth in the scoreless first inning and the wait for home run number 30 continued.

The White Sox scored the game’s first run in the second with their own slugging star, Shoeless Joe Jackson, clouting a home run into the right-field stands. “This made some of the spectators a little impatient,” reported W.O. McGeehan of the New York Tribune. “They began to inquire when the Babe would give them a home run for their price of admission.”3

Ruth finally rewarded the patience of Yankees rooters when he came up again in the bottom of the fourth inning. After a single by first baseman Wally Pipp led off the inning, Babe put the Yankees on the board. Kerr tried to sneak a curveball past the big slugger and “there was a resounding smack as bat met ball and the noise from the stand swelled in volume before the ball started its descent. Every last fan knew that this was the much awaited punch. Nemo Leibold, playing a deep right field for the Wizard of Wallop, backed until his shoulders rubbed against the fence of the right field bleachers and then he gazed upward as the ball sailed over his head. It wasn’t the longest hit Ruth has made into this section, but it was longer than any other ball player ever has hit at the Polo Grounds.”4 Baseball scribe William Hanna commented, “It was a drive worthy of the creation of a new record and of the longest and hardest hitter since time was.”5

The Bambino reveled in his home run and egged on the raucous crowd, according to the New York Times. “While the fans howled in glee, tossed hats around the stand in reckless abandon and made the big stand a mass of waving arms, Ruth completed his journey to the plate and then beamed back with a smile that spurred the crowd on to great exertion, if that were possible. Doffing his cap, the conventional response which usually stills a cheering crowd of fans, had no effect here. Several times on his way to the bench Ruth bowed his acknowledgments, but the din continued after he disappeared in the dugout. His march to the left field at the close of the inning was the signal for another outburst, and the applause was renewed when he came in after the White Sox had been retired in the fourth inning.”6

Then Yankees tacked on another run in the bottom of the sixth when Roger Peckinpaugh led off the inning with a single and was plated by a triple from second baseman Del Pratt. Ruth was unable to score Pratt from third, as Kerr got a measure of revenge by striking out the slugger, but the home team still held a 3-1 lead going into the seventh and seemed well on its way to sweeping the doubleheader.

Things began to turn south for Yankees starter Thormahlen in the top of the seventh. He opened by walking Hap Felsch, then gave up a single to right field by Shano Collins. Swede Risberg promptly drove in Felsch with a single. One out later, Risberg stole second base, and with men on second and third, Dickey Kerr hit a grounder to third, but catcher Truck Hannah dropped the throw from third sacker Aaron Ward, allowing Collins to score the tying run. A double-steal attempt fizzled when Risberg was called out but Nemo Leibold extended the inning with a scratch single past Ward and Eddie Collins followed by singling home Kerr with the go-ahead run.

The White Sox used “small ball” tactics again in the eighth inning to great success and broke the game open with an assist from some more Yankee miscues. Singles from Jackson, Felsch, and Shano Collins loaded the bases to start the inning, prompting Miller Huggins to summon Ernie Shore from the bullpen to try to put out the fire. Shore uncorked a wild pitch that allowed Shoeless Joe to score Chicago’s fifth run. One out later, Shore misplayed Ray Schalk’s bunt when the pitcher’s “feet became entangled, throwing him for a big loss.”7 The result was Schalk safe at first with Felsch scoring on the play. Kerr laid down a sacrifice bunt, and a double steal scored Collins when Hannah’s attempt to nail Schalk at second base went to center field. Leibold singled home Schalk to cap the four-run inning and the White Sox held an 8-3 lead.

The Yankees’ Roger Peckinpaugh responded with a leadoff homer in the bottom of the frame, although “the assassins of Murderers Row did not follow him”8 and the Yankees went into the ninth trailing 8-4.

Ruth’s final chance at individual glory game in the bottom of the ninth, and Babe cracked a solo shot into the lower tier of right-field stands for his 31st homer of the season “although the homer only added to the string of the Babe and did not take the Yanks anywhere.” The Times described an almost melancholy scene, reporting “there was no joy for Babe as he jogged around the bases and back to the bench on the second homer. It arrived when the Yanks were defeated, and that always serves to take interest out of the circuit hits for Ruth, much as the fans revel in such performances, whether the Yanks are winning or losing.”9

The Yankees would continue to experience plenty of wins in 1920, and Babe would continue to raise the bar for the season’s home-run record. The team remained in a three-way pennant chase with Cleveland and Chicago until the end of the season, and eventually finish third behind the Indians and White Sox. Babe took the home-run mark past 40, then 50, finally finishing the season with 54.

W.O. McGeehan of the Tribune reported that The Babe’s 30th home run earned Ruth a film contract worth $100,000,10 and indeed Ruth would make his movie debut that fall in the silent film Headin’ Home. Babe was well on his way to becoming an American pop-culture icon.

The Chicago White Sox went on to become icons of a sort as well. Late in the following season, reports would link them with gamblers and a conspiracy to throw the 1919 World Series. Eight members of the club would go down in history as the Black Sox.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the following:

Crusinberry, James. “Ruth Breaks His Record Twice as Sox Split Even, Chicago Tribune, July 20, 1920: 5.

Hanna, William. “Ruth Hits Two More Home Runs, Increasing His Total to Thirty-One and Setting a New High Record, The Sun and New York Herald, July 20, 1920: 11.

Somerville, Charles. “Ruth Gets Two Homers, Breaking World’s Record, but Yanks Lose Game,” New York Evening World, July 20, 1920: 19.

Notes

1 Reports of the attendance vary. Retrosheet and Baseball Reference box scores cite 20,000, while contemporary newspapers pegged the attendance higher. The Chicago Tribune reported 25,000, the New York Tribune 26,000, the Sun and New York Herald 27,000, and the New York Times, 28,000.

2 W.O. McGeehan, “Ruth Breaks Home Run Record, Wins $100,000 Film Contract,” New York Herald, July 20, 1920.

3 Ibid.

4 “Babe Sets Record, Then Adds Another,” New York Times, July 20, 1920: 8.

5 McGeehan.

6 “Babe Sets Record, Then Adds Another.”

7 McGeehan.

8 Ibid.

9 “Babe Sets Record, Then Adds Another.”

10 McGeehan. Jane Leavy reports that the contract was for $50,000 and, further, “He got $15,000 up front and got stiffed for the rest when the producers went belly-up.” Jane Leavy, The Big Fella (New York: Harper, 2018), 228, 229.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 8

New York Yankees 5

Game 2, DH

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.