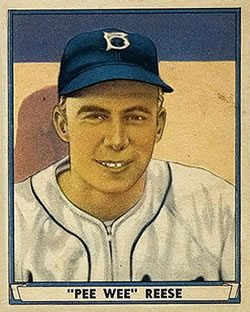

June 1, 1940: Pee Wee Reese gets beaned by Cubs, leading to bleacher changes at Wrigley

Babe Ruth joined the Brooklyn Dodgers as they traveled by train to Chicago for three games at Wrigley Field in the first half of the 1940 season. A baby-faced rookie shortstop known as the Little Colonel was likely in awe of the stardom. But the game’s most famous player could not have advised Pee Wee Reese on the park’s “10th Man” that lurked in the outfield bleachers,1 as those bleachers were constructed after Ruth’s playing days in 1937. What happened in extra innings on June 1, 1940, would go on to influence how batters could protect themselves in the batter’s box and help add a distinct element to the outfield bleachers at Wrigley Field.

Babe Ruth joined the Brooklyn Dodgers as they traveled by train to Chicago for three games at Wrigley Field in the first half of the 1940 season. A baby-faced rookie shortstop known as the Little Colonel was likely in awe of the stardom. But the game’s most famous player could not have advised Pee Wee Reese on the park’s “10th Man” that lurked in the outfield bleachers,1 as those bleachers were constructed after Ruth’s playing days in 1937. What happened in extra innings on June 1, 1940, would go on to influence how batters could protect themselves in the batter’s box and help add a distinct element to the outfield bleachers at Wrigley Field.

A crowd of 8,855 entered Wrigley Field that Saturday to watch the skidding Dodgers (21-10, two games behind Cincinnati), and Cubs (18-19, eight games back). It was the Dodgers’ Tex Carleton on the mound, fresh off a no-hitter, going for Brooklyn. He would roll through the early frames, going up 3-0 against the Cubs’ Ken Raffensberger. The sixth inning saw the Cubs tie the game, 3-3. It remained stalled at 3-3 into extra innings.

With two out and no one on in the top of the 12th inning, the Cubs pitcher, right-handed-throwing Texan Jake Mooty, delivered a pitch to Reese. Reese lost sight of the pitch among the white shirts worn by spectators in the center-field bleachers. The white ball struck Reese just behind his unprotected ear, dropping him limp on his back. The Dodgers dugout quickly sprinted to tend to the likable shortstop.2

Conscious but disoriented, Reese was put on a stretcher and ambulanced to nearby Illinois Masonic Hospital. Reese mentor and Dodgers manager Leo Durocher pinch-ran and took his place at shortstop. But the Dodgers’ spirit was deflated and the first Cub to bat in the bottom half, former Dodger Al Todd, hit a 400-foot home run to win the game.

There was a Sunday doubleheader the next day, but the Dodgers were more concerned about the results at the hospital. Reese was their promising new 20-year-old shortstop coming at a high cost of $75,000. Reese had the skills and the demeanor to lead the Dodgers franchise into the future. Larry MacPhail, Brooklyn’s general manager, took a big risk with Reese. The Boston Red Sox has seen him as so important that they bought the Louisville Colonels team to ensure that they got him. But now he was a Dodger and the seasoned baseball man MacPhail called him “the most instinctive baserunner I have ever seen.”3

Reese spent 10 days at the Chicago hospital before spending more time back home in Louisville recuperating from the “severe concussion.”4 The day after Reese was pegged, the Chicago Tribune reported that 23-year-old Lyle Neuman of Wilmot, Wisconsin, had died days after getting beaned in a Wisconsin Rural League game.5 Reese returned on June 21 to hit a single, double, and triple. Neuman could not.

To make matters worse, three days before Reese’s return, his teammate Joe Medwick was knocked unconscious at Ebbets Field from a blatant beaning by Bob Bowman to finish an argument that began at a hotel.6 The constant baseball visionary MacPhail took note. Although there had been flirtations with designing batters’ helmets since Ray Chapman’s death in 1920, baseball leaders and players were still hesitant regarding the idea.

On June 29 NL President Ford Frick and other league brass met in St. Louis to discuss the increasing problem, citing the Reese and Medwick incidents. These head injuries became a rallying point for McPhail and Frick to “galvanize the targeted development of protective headgear.”7 MacPhail partnered with orthopedist Dr. George E. Bennett of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

The 1941 season saw the Brooklyn Dodgers utilize an early form of the batting helmet with Reese and Medwick the first users. Dubbed a “beanball hat,”8 it was a regular baseball cap with plastic plates sewn into the side interiors. It earned the praise of MacPhail, who in 1941 called it “the biggest thing that has happened to the game since night baseball — which he also helped create. By the end of the 1941 season, four teams had adapted the new gear.9

In June 1941, with the Reese scare still fresh in Brooklyn, the New York Daily News penned a letter to Cubs owner Philip Wrigley in Chicago demanding that he do something to assist the batters’ vision at Wrigley Field.10 The letter cited the most recent victim of the “white shirt problem,” Cubs All-Star Hank Leiber who was severely injured at Wrigley on June 24 from a Cliff Melton pitch — lost in the shirts as usual. Chester Smith of the Pittsburgh Press passionately expanded upon it, calling it “one of the most unusual letters ever written to a club owner.”11

Smith added, “For years now, both Cubs and visiting players have complained of poor visibility by the low bleachers. It is the worst background for judging a pitched ball in the majors. Lieber didn’t see the pitch that hit him until the last second. Even the umpire, Babe Pinelli, lost sight of the pitch. Lost it because the ball came out of the shimmer of the white shirts of fans seated in those bleachers in direct line of home plate. Pee Wee Reese suffered the same experience last year when felled by Jake Mooty.”12 Smith’s article was accompanied by a cartoon captioned, “Ahh Forbes Field. You never get beaned at this park!”13

With the “White Shirt Problem” now exposed, it would pick up steam. Research indicates that complaints from National League players about the batting background at Wrigley increased with regularity as the 1940s moved on, and especially as baseball normalized after World War II. When Boston Brave Tommy Holmes’s 37-game hit streak in 1945 was broken at Wrigley Field, he said, “[L]ooking out into that white background was tough. A couple of [Hank] Wyse’s pitches were at my chin before I knew it.”14

Although reluctant, Cubs owner Wrigley started to experiment, eventually adding a shade screen for right-handed hitters to the center-field bleachers during the 1947 season.15 Likely due to the increased criticism received around the 1947 All-Star Game at Wrigley Field,16 a cartoon poking fun at the Cubs’ “much discussed white shirts” appeared in the Boston Globe in June 1947.17 After the All-Star Game, with American Leaguers now stepping in at Wrigley, Joe DiMaggio said, “It’s bad, they really ought to do something about it.”18 Detroit Tiger George Kell said, “It’s rough.”19

In 1951 Cardinals manager Ed Stanky demanded that the center-field bleachers (1,200 seats) be roped off while his team was there.20 That process finally became permanent for the 1952 season,21 due part to efforts by Hank Sauer22 and Ralph Kiner23 among others. Sauer would ignite at Wrigley to win the 1952 NL Most Valuable Player Award, perhaps aided by the new hitter’s advantage. The bleacher seats would remain in place to be used for Chicago Bears games until the 1970s, but were fenced off during baseball season. The space would eventually be converted into green juniper shrubbery in 1997.

Baseball, with its spirit largely based on tradition, can be slow to change. This 1940 game and its one errant pitch served as a catalyst toward providing momentum to solve one of the game’s safety issues and give one of its parks some much needed refining.

Sources

https://baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHN/CHN194006010.shtml

https://retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1940/B06010CHN1940.htm

Shea, Stuart. The Long Life and Contentious Times of the Friendly Confines (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014).

Spatz, Lyle, ed. The Team that Forever Changed Baseball and America: The 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press/SABR), 2012.

Notes

1 Hy Turkin, “Cubs Beat Dodgers 4-3; Pee Wee Reese Beaned,” New York Daily News, June 2, 1940: 79.

2 Tommy Holmes, “Reese in Hospital, Injured as Dodgers Bow to Cubs,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 2, 1940: 1C.

3 Tommy Fitzgerald, “Brooklyn in $75,000 Deal for Reese, Who ‘Didn’t Want to Be a Dodger.’” The Sporting News, July 27, 1939.

4 Irving Vaughn, “Todd Breaks Up Dodger Opener, 4-3; Reese Hurt,” Chicago Tribune, June 2, 1940: Section 2, 2. “Pee Wee Reese Quits Hospital, Returns Home,” Chicago Tribune, June 11, 1940: 23.

5 “Kenosha Ball Player Dies; Beaned in Game,” Chicago Tribune, June 2, 1940: Section 2, 1.

6 “Dodgers Seek Ban on Bowman as His Pitch Fells Joe Medwick,” Chicago Tribune, June 19, 1940: 23.

7 “The Neurosurgeon as Baseball Fan and Inventor: Walter Dandy and the Batter’s Helmet,” in Neurosurgeon FOCUS 2015, Department of Neurosurgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

8 Bob Hurte, “The Story of the Beanball Hat,” Seamheads.com, February 22, 2013, seamheads.com/blog/2013/02/22/the-story-of-the-beanball-hat/. Accessed May 21, 2019.

9 “The neurosurgeon.”

10 “N.Y. Writers Give Wrigley Bean Ball Tip,” Chicago Tribune, June 26, 1941: 19.

11 Chester L. Smith, “The Village Smithy — ‘Bean Ball’ Parks Are Menace to Players,” Pittsburgh Press, June 28, 1941: 7.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Jerry Liska, “Cubs Park Is ‘Hardest,’ Says Tommy Holmes,” Allentown (Pennsylvania) Morning Call, July 15, 1945: 9.

15 “Wrigley Field Experiment,” Decatur (Illinois) Daily Review, July 23, 1947: 8.

16 Harold C. Burr, “Batting Background Plays Villain Role,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 3 1947: 23.

17 Gene Mack, “Wrigley Field, Scene of All-Star Game,” (cartoon), Boston Globe, July 9, 1947: 14.

18 “Pitches Resemble those Discs with Blackie and Hal on Hill,” Syracuse Post-Standard, July 7, 1947: 15.

19 Ibid.

20 Sauer Big Reason for ChiCubs Pace,” Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News, June 10, 1952: 24.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Al Yellon, “A History of Wrigley Field Changes,” bleedcubbieblue.com/2013/4/15/4226660/wrigley-field-renovations-history, accessed April 26, 2019.

Additional Stats

Chicago Cubs 4

Brooklyn Dodgers 3

12 innings

Wrigley Field

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.