June 30, 1921: Pirates’ Moses ‘Chief’ Yellow Horse defeats Reds’ Adolfo Luque

All major-league franchises have had their share of noteworthy moments concerning the racial aspects of the sport’s chronicle. The Pirates, for example, have participated in one of the most renowned events in this narrative, with the game on September 1, 1971, a prime example. On that evening at Three Rivers Stadium, manager Danny Murtaugh wrote out a lineup card that featured the first all-minority starting nine in major-league history.

All major-league franchises have had their share of noteworthy moments concerning the racial aspects of the sport’s chronicle. The Pirates, for example, have participated in one of the most renowned events in this narrative, with the game on September 1, 1971, a prime example. On that evening at Three Rivers Stadium, manager Danny Murtaugh wrote out a lineup card that featured the first all-minority starting nine in major-league history.

Pittsburgh was also enmeshed in a lesser known racial episode — the first time an African-American managed in the majors. That mostly ignored happening occurred on September 21, 1963, when Murtaugh and coach Frank Oceak were both tossed for arguing a call late in a contest against the Los Angeles Dodgers. The man who skippered the Bucs over the last two innings of that game, Gene Baker, not only broke down the managerial barrier (albeit but briefly) at the highest level, he was also the first man of his background to manage a minor-league squad for a major-league organization (when the Pirates signed him to manage Class-D Batavia in 1961). The story described here falls into this second, less well-recognized, category; though it is no less significant. On June 30, 1921, for only the third time in major-league history, both starting pitchers were nonwhite: one Latino (Adolfo Luque) and the other Native American (Moses Yellow Horse, a Pawnee).

A review of the careers of both men demonstrates the stereotypes so prevalent for Latinos and Native Americans at play during these years. The Cuban-born Luque was a “hothead,” and the Native American competitor was someone who could have triumphed if only he had not been (genetically, it would have been argued then) susceptible to liquor. The two previous occasions for such a matchup took place that same season, when the Luque faced off against Cubs hurler Virgil Cheeves (Cherokee) on May 5 and June 25. The right-handed Luque also pitched in another historic start, on September 2, 1918, when he and fellow Cuban Oscar Tuero became the first Latino tandem to oppose each other on a major-league mound.

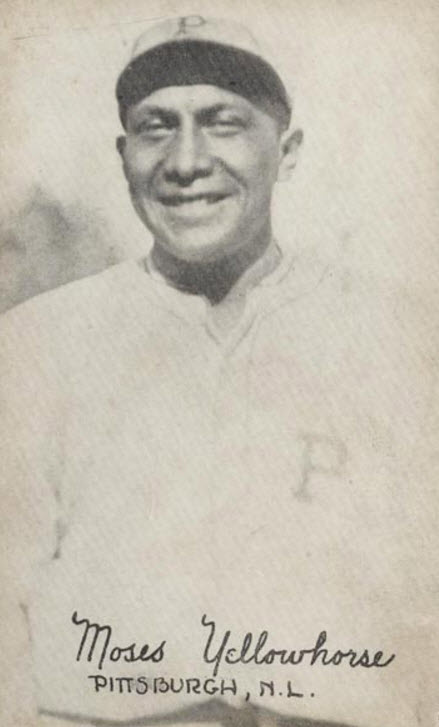

Moses Yellow Horse had a brief but significant, career with the Pirates, playing in only 38 games, starting eight and finishing with eight victories, four defeats, and one save. Overall, he toiled for 126 innings and finished his time in the majors with a 3.93 ERA. Yellow Horse’s story has been covered in various works, but the most important rendering comes from Jeffrey Powers-Beck in his 2004 book, The American Indian Integration of Baseball.1 Not surprisingly, Yellow Horse and other Native Americans endured “verbal and physical abuse both on and off the diamond” as he made his way up to the majors.

He started in the sport “late,” given the paucity of equipment and facilities at the Pawnee Agency. In Oklahoma, Yellow Horse started by playing for the Chilocco Indian School team in 1916, and also played for Ponca City in the “Horseback League.” He subsequently came to the attention of Des Moines of the Class-A Western League, which signed him in 1918. After success in that circuit, a former teammate with Chilocco recommended him to the Arkansas Travelers, where Moses helped the squad win the Class-A Southern Association pennant in 1920 by going 21-7. This was where Yellow Horse came to the attention of the Pirates, who bought his contract for $8,000. Powers-Beck argues that “although he lasted only two big league seasons, the sale was a bargain for Pirate fans.”2

The young hurler made an immediate impact with the Pirates. On Decoration Day of 1921, for the first time, the fans at Forbes Field shouted out what would become a rallying cry for the team’s aficionados: “Put in Yellow Horse!” On that holiday, May 30, the Pawnee pitcher cemented his status with fans by going 7⅔ scoreless innings and helping the Pirates to a 6-3 game-two victory over the Chicago Cubs to sweep a doubleheader. His response to the adulation was “restrained and gentlemanly,” and he soon befriended other players, such as Drew Rader and Rabbit Maranville.

Unfortunately, as many players of this era did, Yellow Horse (and particularly, Maranville too) imbibed quite a bit, and the rabble-rousing eventually led team owner Barney Dreyfuss to rid his team of the presence of what many in the majors considered to be nothing more than a “drunken Indian.” The Pirates sold Yellow Horse to Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League for 1923. There, he continued to shine, sporting a 22-13 mark for the Senators.3 Local papers did not note any behavior problems (alcohol-related or otherwise) that would have kept Yellow Horse from returning to the majors. But a shoulder injury in 1924 in a game against the Salt Lake City Bees created control problems and decreased the speed of his fastball, making a return to the big leagues impossible. Subsequently, “depressed and with a badly aching arm, Moses resorted to liquor as his painkiller of choice.” As Powers-Beck noted in his work, on cue, The Sporting News played up the “drunken Indian” stereotype, stating that “Chief Moses Yellow Horse has gone the way of all bad Injuns. The Chief would not keep in condition, and was no longer of use to the team.”4

All the negative events noted above lay in the future, however, as one month beyond his Decoration Day heroics, Moses Yellow Horse had the fans in Pittsburgh once again voicing their acclaim of his pitching prowess after he took the mound and went the distance in a contest against the Cincinnati Reds.

The Pirates hurler was sharp from the opening frame, with a quick first, striking out Sam Bohne, inducing a fly out from Jake Daubert, and walking Heinie Groh, who was then caught stealing. The Pirates broke through in their half of the frame, with singles by Carson Bigbee, a fly out by Max Carey , a single by Maranville, a fielder’s choice by Clyde Barnhart, and a triple by Ray Rohwer plating two tallies. Cotton Tierney popped out to third to end the rally.

The score remained 2-0 until the top of the fifth. In that inning, the Reds broke through after two outs on walks to Larry Kopf and Rube Bressler and a two-run double by Luque that tied the score. The Pirates put the game away, and knocked out the Latino hurler, scoring three in the bottom of the seventh with a double by Charlie Grimm , a single by Walter Schmidt, a single by Bigbee, a double by Carey, and a single by Maranville. This flurry chased Luque, who was replaced by Lynn Brenton on the hill for the Reds. Cincinnati scored a final run in the top of the eighth on a walk to Ivey Wingo, a wild pitch by Yellow Horse, and a single by Pat Duncan. In the ninth, the visitors went down in order with Bressler grounding out, Bubbles Hargrave (who batted for Brenton) doing likewise, and finally Bohne flying out to end the game.

While his record with the Pirates was excellent, it appears that team management, swayed in part by the stereotypical perception of Native Americans extant at that time (and also some inappropriate behavior by Moses as well), gave up on Yellow Horse too quickly. Here was a pitcher who had a decent 2.98 ERA in 1921 and won twice as many games as he lost (8-4) over a truncated two-season major-league career. Perhaps if the Pirates had not been so quick to pull the trigger on getting rid of him, Yellow Horse might have contributed to other squads during the 1920s and even beyond. Yellow Horse returned to Oklahoma and lived out the remainder of his life on the agency, passing away in 1964.

For Yellow Horse’s opponent on the mound this day, there were also examples of how the broader American society stereotyped Latinos; for example, an incident that took place in Cincinnati in 1923 in which Luque charged outfielder Bill Cunningham of the Giants after enduring numerous “remarks” about his Cuban heritage. Even though he was a member of two World Series winners (the 1919 Reds and the 1933 Giants), Luque’s nearly 200 major-league victories are often overlooked in lieu of characterizing him as a “hot-headed” Latin. Thus, on this day at Forbes Field, two pitchers who overcame great odds to make their way to the majors squared off and pitched well. Their mere presence on the mound that day was a challenge to the racial/ethnic status quo. This is yet another historically significant moment in Pirates history that deserves to be remembered.

This article appears in “Moments of Joy and Heartbreak: 66 Significant Episodes in the History of the Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2018), edited by Jorge Iber and Bill Nowlin. To read more stories from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited below, this essay also utilized information from Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PIT/PIT192106300.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1921/B06300PIT1921.htm

Notes

1 Jeffrey Powers-Beck, The American Indian Integration of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004).

2 Powers-Beck, 143-144, 148-149.

3 Powers-Beck, 156-158.

4 Powers-Beck, 159.

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Pirates 5

Cincinnati Reds 3

Forbes Field

Pittsburgh, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.