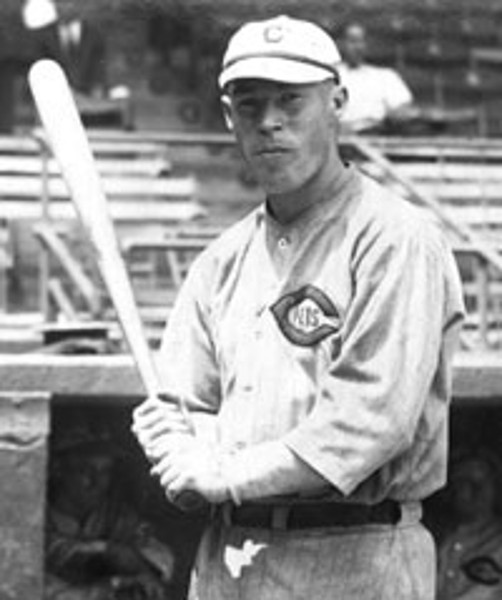

Bubbles Hargrave

It was one of the most bizarre batting races in National League history. Three players on the same team were competing for a batting championship, none of whom today would qualify for the honor. Not until December of 1926, nearly three months after the season ended, was it decided whether Bubbles, Cuckoo, or Rube had won the coveted honor. That Bubbles Hargrave rose to the top in winning the title made baseball history. He was the first catcher in the modern era (post-1900) to earn this distinction.

It was one of the most bizarre batting races in National League history. Three players on the same team were competing for a batting championship, none of whom today would qualify for the honor. Not until December of 1926, nearly three months after the season ended, was it decided whether Bubbles, Cuckoo, or Rube had won the coveted honor. That Bubbles Hargrave rose to the top in winning the title made baseball history. He was the first catcher in the modern era (post-1900) to earn this distinction.

However, there was more to Hargrave than this statistical achievement. In an era when catchers like Mickey Cochrane and Gabby Hartnett played their way into the Hall of Fame, Hargrave more than held his own as a quality backstop.

Eugene Franklin Hargrave was born on July 15, 1892, in New Haven, Indiana, the son of Franklin and Rebecca Hargrave. Franklin, a North Carolinian, was a veteran of the Civil War, having served in the 121st Ohio regiment, a unit that saw continuous action in engagements which included the battles of Chickamauga, Lookout Mountain, and Atlanta.1 The elder Hargrave’s military service was ingrained into family history. Eugene’s oldest brother Robert was a veteran of the Spanish-American War; another brother, Harry, served in the Army during World War I.2

Despite a heritage of military history in his family, young Eugene showed an early interest in becoming a professional baseball player. His father opted for a more stable career for his son, however. As young Hargrave later reminisced, “So I went into the upholstering business. I didn’t like it because there was too much dust.”3 His career in this line of work apparently was short, as he began his professional baseball career at just 18, catching for the Class B Central League, Terre Haute Miners in 1911. He played 91 games and hit .285 for the unaffiliated ballclub. He played the next two seasons there before his contract was purchased by the Chicago Cubs in August 1913. Hargrave appeared in three games at the end of the season for the Cubs.

Over the 1914 and 1915 seasons, he backed up the likes of solid veteran Jimmy Archer and future Hall of Famer Roger Bresnahan. As a third-string catcher, Hargrave’s appearances and impact were minimal—he appeared in just 38 games, mostly as a late-inning replacement, while batting a meager .200 over the two years. Although both Archer and Bresnahan were on the downsides of their careers, Hargrave failed to make headway and was sold to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association to begin the 1916 season. After 1916 and 1917 with the Blues, he landed with the St. Paul Saints. His acquisition was engineered by Mike Kelley, who managed the Saints. Kelley had a 30-year career as manager and owner within the American Association, his longevity due in part due to a sharp eye for talent.4

The Saints won the American Association championship in 1919 and repeated in 1920 with a 115-49 record, 28 ½ games ahead of the Louisville Colonels. An extremely talented team, 16 of the 22 players on the 1920 Saints roster played in the majors at one time or another. For his part, Hargrave had a breakout year, hitting 22 home runs, second in the league, and batting .335, narrowly missing the batting title. His accomplishments earned the attention of several major league teams including the Yankees. Cincinnati won out, bidding $10,000 for his services. Hargrave had been recommended to Cincinnati by former Reds pitcher Charlie Hall early in the 1920 season.5

The Cincinnati Enquirer’s comments on his purchase also made note of Hargrave’s earlier history with the Cubs, that he “did not develop enough consistency in his work at that time to become a regular.” The writer felt that he had “married and settled down and is taking his work more seriously than he formerly did.” This was in reference to Hargrave’s having married Hester Wolf on May 20, 1918, in Allen County, Indiana. The marriage lasted 50 years and produced a son, Eugene Neiland, in 1921.6

In coming to the 1921 Reds, Hargrave was joining a team that just two years earlier had won the World Series. Ivey Wingo, a ten-year veteran, at 30, was a solid backstop but had not mastered left-handed pitching, a deficit Hargrave was expected to fill. Going into the season he faced a major challenge. Was he major league material and had he matured from his earlier, ineffective days with the Cubs?

All references to the newly-acquired Hargrave referred to him as “Bubbles.” How he actually acquired that nickname has been lost over time. One version shared by Hargrave was that a teammate bestowed it on him because he was effervescently offering suggestions and guidance.7 Still another version concerned his tendency to stutter, especially when pronouncing the letter “b” which somehow caused him to be referred to as Bubbles.8 His stuttering manifested itself in another form at least once on the ball field.

Apparently when he became excited his jaw tightened. Arguing with umpire Ted McGrew late in his career, he couldn’t get any words out. McGrew told Hargrave, “Never mind, Bubbles. I’ll help you out. I’ll say what you want to say. McGrew, you’re the lousiest umpire in the world. You never was any good. You’re blind and dumb. You ought to be in some other business.” Hargrave, jaw now relaxed could only say, “You win.”9

Cincinnati disappointed in 1921, tumbling from third to sixth, the decline based on an anemic offense caused in part by the loss of playing time from holdouts Heinie Groh and Edd Roush. That disappointment did not attach itself to Hargrave, who batted .289 as part of a platoon with Wingo, demonstrating he could hit in the big leagues. Although he only hit one home run (the team total was a league-worst 20) his 17 doubles and eight triples contributed to a .426 slugging average, second only to Roush on the team. Hargrave was on his way toward establishing himself as one of the best catchers in the league. Not only was his offense solid, but The Cincinnati Enquirer characterized him as having a “powerful and accurate arm and is a bulwark in blocking runners at the plate. No one is going to slide around or past him when he has the ball in his hand.”10

Over the next several seasons Cincinnati improved, often in contention but never good enough to take the pennant. Hargrave was a major part of the upturn. Beginning in 1922, Hargrave batted over .300 six consecutive seasons. A look back at his career from today’s 2017 vantage point must consider the prism of time. Hargrave’s batting and slugging marks for catchers during this era ranked near the top. His hitting ability did not lend itself to home runs, but rather line drives that produced doubles and triples. Regardless of measuring in average, slugging, or on-base percentage—metrics used nowadays to measure a player’s worth—Hargrave’s career numbers were on a par with later Cincinnati catcher (and Hall of Famer) Ernie Lombardi.11

While renowned for his offensive skills, Hargrave had defensive capabilities that were less well defined. From a perspective of nearly 80 years from the end of his career, the rating of his defensive skills based on then-existing data is, at best, a murky endeavor. Although no less an authority than Bill James rates Hargrave as “just a fair defensive catcher,” contemporary accounts reflected a better-than-satisfactory assessment of his abilities.12 He had a powerful throwing arm and he was savvy in his handling of pitchers.13 No less a personage than John McGraw described him in 1926 as “the greatest catcher in the game.”14

Paradoxically, Hargrave found catching in the majors easier than in the minors. Reminiscing on his career, he observed, “I remember when I was in the American Association. I found it much harder to work there than in the majors. Big league pitchers have much more experience and a catcher doesn’t have much to do. In the minors I had my hands full with those inexperienced pitchers. I don’t know of anything more discouraging than catching a green pitcher.”15

Hargrave’s career was often interrupted by injury or illness. In May 1924 he was hit on the hand by a pitch. A resulting broken bone kept him out of the lineup for nearly a month.16 Less than a year later, Hargrave was injured by a foul tip that kept him out of the lineup for several weeks early in the season.17 When he came back his play reflected his worst showing since joining the Reds. Appearing in just 87 games in 1925, Hargrave batted an even .300, with a slugging average of .414 both, below prior production. He was 33, and as a catcher, there was cause for wondering whether his best days were behind him.

Hargrave’s injuries and their impact on his play were on the mind of Cincinnati’s club president August Hermann when he initiated correspondence with Hargrave in January 1926. The communications between them, found in Hargrave’s player file at the Hall of Fame, open a window on the relationship between owner and player in the 1920s.

Herrmann wrote asking Hargrave if he had recovered from his injury of the previous season (1925). Hermann wanted to know what Hargrave’s “ideas are with reference to your contract for 1926.”18 Hargrave said that he was fully recovered and wished to discuss a “substantial increase.” 19 Hermann quickly replied that “it is entirely out of the question to give you . . . any increase at all.” He enclosed two copies of Hargrave’s new contract asking they be signed or Hargrave advise otherwise, “so we can make other arrangements.”20

Hargrave returned the unsigned contracts, advising, “I cannot convince myself that I am being unfair in asking for an increase. … ”21 A week later Hermann returned the contracts repeating his earlier comment about making other arrangements.22

Hargrave had no leverage but he still tried to get Hermann to pay his wife’s expenses to accompany him to spring training. Hermann denied the request, advising unless the contracts were returned signed, “negotiations will be called off.”23 What in the correspondence led Hermann to think he was negotiating with Hargrave remains unseen. Without a choice in the matter, Hargrave subsequently signed for no increase.

On the eve of Opening Day in 1926, Hargrave experienced another setback when stricken with appendicitis.24 Although seemingly dire, it proved a lucky break for Hargrave in the long run. After it was determined he would not have to undergo surgery, Hargrave was placed on a liquid diet, mostly buttermilk, and lost fourteen pounds in the process. He later claimed this regime improved his vision.25

Whether due to diet or not, his recuperation was rapid and effective. Appearing for the first time in the 10th game of the 1926 season, he went on a tear. By the end of May, Hargrave was batting .432; the last day of June his average stood at .424. Meanwhile, Cincinnati was making a run for the National League pennant. Led by standout pitching from Pete Donohue (20 wins), Carl Mays (19 wins), and solid years from Edd Roush (.323) and Wally Pipp (.291), the Reds remained in the pennant race all season long with the Cardinals. As the season rolled into September, the race generated great interest. St. Louis was the only major league city (Browns or Cardinals) that had never captured a league championship during modern times. This, and Cardinals’ playing manager Rogers Hornsby’s inspired leadership, contributed to the excitement.

Although he was providing effective leadership, a host of various ailments had reduced Hornsby’s effectiveness at the plate during the year. After having batted an aggregate .397 the previous six seasons, giving him six consecutive batting titles, Hornsby entered September 1926 with an un-Hornsby-like .314 mark. He stood considerably below players like Pittsburgh’s George Grantham and Pie Traynor, as well as St. Louis’s Les Bell—each of whom were among the league leaders with averages in the .330 range.26

Sportswriter and former American League umpire Bill Evans picked up on this development in “Billy Evans Says,” his nationally-syndicated column. Evans mused on the expected change in batting leaders. “… [W]ith the end of the chase but five weeks away, there doesn’t seem much possibility of Rogers Hornsby overhauling the pacesetters.” Evans cited Traynor, rookie Babe Herman of the Dodgers and Cincinnati’s Rube Bressler as likely candidates to unseat Hornsby as lead batsman.27

Evans, in mentioning Bressler among the batting leaders, thought he would soon return to action from an appendicitis attack and “take part in more than 100 frays, the number usually necessary before a player is figured a regular.” Evans was citing an unwritten rule that a player must appear in 100 games to qualify for the batting title. Bressler, batting .357 when forced out of the lineup in late August, never did return to action and appeared in just 86 games. Meanwhile Hargrave was hitting at a .369 clip although had appeared in only 83 games through August.

The Cincinnati Enquirer, in observing Hargrave leading all batters, hedged by commenting, “ . . . although none of the leading Red performers have played as many games as the regulars among other contenders.”28 A mention of Cincinnati batting leaders also included Reds’ rookie outfielder Walter “Cuckoo” Christensen, whose .350 mark has put him in the thick of the race. He had played in 89 games through August.

Individual statistical developments were mostly ignored as the pennant race roared into its final month. As late as September 15, Cincinnati was ahead of St. Louis, but a six-game losing streak doomed them. The Reds ultimately finished second, two games behind Hornsby’s Cardinals, giving the Gateway City its first pennant in the 20th century.

After the season ended, league statisticians went to work compiling the years’ numerical achievements. The final sifting of numbers for batting in the National League confirmed Bressler’s .357 in 86 games. Hargrave batted .353 in 105 games, with Christensen compiling a .350 mark in 114 games. With statistics confirmed, the question came up as to who led the league in hitting. The matter was still unsettled in mid-December, partially because the issue of what determined a batting leader had never been examined.

Nap Lajoie had hit .329 in 1905, well above Elmer Flick at .308, yet Flick was declared champion since Lajoie had played just 65 games because of injuries. Bill James notes Billy Southworth in 1918 achieved the highest average in the National League. While there was some sentiment for awarding Southworth the title, the consensus was that his having played in only 64 games disqualified him.29

Playing in a minimum of 100 games had credence in the minds of many. Evans had noted it in his article, while Jack Ryder vaguely touched on this standard in an article for The Cincinnati Enquirer. When discussing Hargrave, he mentioned that the catcher had “played in 105 games, or more than two thirds of all the championship contests.”30

The matter came to John Heydler, president of the National League. He tried without success to establish a uniform standard for a contender to qualify, and then announced his decision that Hargrave should be recognized as the batting leader. And there the matter stood. Plans to set a standard were squelched as “no arbitrary limit would work out satisfactorily,” to the agreement of all.31

Failure to set a standard would prove to be a statistical thorn in the side of baseball for the next 30-plus years until the present standard of basing qualifications on plate appearances came into being in the 1950s. During the interim, at least four batting titles were questioned for lack of a qualifying standard.32 Under today’s qualification standards, the 1926 title would have been awarded to Pittsburgh rookie Paul Waner, whose 618 plate appearances more than met the minimum standard. Waner hit .336 in 1926 and, had he won, would have been the first rookie to win a batting title.

Hargrave’s accomplishment carried distinction, however. Long-time observers of the game pointed out that Hargrave was the first catcher to win a batting title since Mike “King” Kelly took the crown in 1886.33 Hargrave was the first catcher to achieve this in the 20th century. It would take 12 years for another catcher to repeat Hargrave’s accomplishment. Ironically, Ernie Lombardi, another Reds’ catcher, won the 1938 title. Lombardi would win again in 1942.34 Hargrave’s performance in 1926 was not lost on those within the game; he finished sixth in voting for the Most Valuable Player award, which went to another catcher, Bob O’Farrell of the pennant-winning Cardinals.

Given the tenor of the times, how Hargrave felt about winning the batting title went unrecorded. Winning the title allowed him to do something he was not able to do prior to the 1926 season—hold out. As the 1927 season rolled around, he failed to report to spring training. After several weeks the Cincinnati press reported that his holdout ended—this time Hargrave received a raise.35

The Reds’ near miss in 1926 proved their high water mark of the decade. In 1927 they dropped to fifth, and didn’t return to the first division until 1938. Hargrave was one of the few Reds to have a respectable year in 1927, finishing at .308, best on the team. However it was an effort devoid of power, as the 34-year-old receiver had no home runs and a slugging average of just .387, the first time Hargrave had slugged below .400 since joining the Reds.

After the 1927 season, the 68-year-old Herrmann retired as president of the Reds.36 His successor, C. J. McDiarmid, did not look favorably on players who had a history of holdouts.37 Hargrave’s age and salary made him expendable. Prior to the 1928 season rumors circulated that the Giants were interested in obtaining Hargrave but McDiarmid had nixed the deal as unsatisfactory.38 The trade would have involved sending Hargrave and shortstop Hughie Critz to the Giants for Hornsby.39 At 35 years old, Hargrave remained with Cincinnati in 1928 but began to show his age, hitting .295 after topping .300 for six straight seasons.

After the season Cincinnati put him on waivers. Surprisingly, Hargrave cleared and was sold to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association to become a playing manager. After the transaction was announced, it was revealed that Dodgers’ manager Wilbert “Uncle Robby” Robinson had claimed Hargrave but was dissuaded by Reds’ manager Jack Hendricks. Hendricks reportedly explained to Robby that this was a way to give Hargrave some consideration for his service to Cincinnati and was a deal that would benefit Hargrave. The transaction was strongly supported by Saints’ owner Bob Connery. Only then did Robby relent. Hargrave, just two years removed from having led the National League in batting, was moving back to St. Paul where he had enjoyed great success during the 1919-20 seasons.40

Managing a team that featured 18 former or future major leaguers including the likes of shortstop Bill Rogell and pitcher Russ Van Atta, Hargrave guided the 1929 Saints to second place.41 Along the way, Hargrave caught most of the games and hit .369 on the year. His performance gained the attention of the Yankees who were seeking to shore up their catching ranks behind Bill Dickey. That St. Paul and the Yankees made a deal was no accident. Yankees’ manager Miller Huggins was a silent part owner of the Saints. His last baseball transaction before passing away at the end of the 1929 season was to obtain Hargrave for the 1930 campaign.42

Hargrave came to a Yankee team in transition managed by Bob Shawkey. They had finished second behind the Philadelphia A’s in 1929 after having won six American League pennants from 1921 through 1928. Hargrave did reasonably well, batting .278 in 45 games, sharing reserve duties with Benny Bengough. But an injury sustained in late July limited Hargrave; he appeared in only three games thereafter, his last on September 6 when he started a game, only to depart in the first inning after splitting his finger on foul ball. Although his 1930 appearances were limited, they afforded the opportunity for Hargrave to play in two games against his younger brother Pinky—first on May 12, then on July 20. Pinky, then with the Tigers, was in the seventh season of his ten-year major league career.

As 1930 ended Shawkey was let go, replaced by Joe McCarthy. Within a few weeks both Bengough and the 38-year-old Hargrave were released. Hargrave’s lack of power and speed made him expendable.43 His major league career was over. Over 12 seasons he appeared in 852 games, compiling a lifetime batting average of .310 with a .452 slugging percentage. In addition to winning the batting title in 1926, Hargrave led the National League in fielding in 1927 and for his work in Cincinnati he had earned a reputation as one of the senior circuit’s premier catchers.

He caught on with his former manager, Mike Kelley, as backstop for the Minneapolis Millers for the 1931 season, appearing in 117 games and batting .305 on the year. In 1932 he moved to the Buffalo Bisons in the International League. The old-timer proved he could still hit, batting .372 in 83 games. Since he had signed a one-year contract with the understanding he would be given his unconditional release at the end of the season, Hargrave found himself looking for employment for 1933. An article in the Enquirer during the early spring of that year mentioned he was applying to manage the Grand Forks, North Dakota, team of the newly formed Northern League.44 Nothing came of it.

Out of baseball for a year, in 1934, Hargrave again appeared on the field, this time as playing manager for the Cedar Rapids Raiders in the Western League. Late in the season he stepped down a as a player due to failing eyesight. He was hitting .254, mostly as a pinch-hitter when he resigned.45 With that, the 41-year-old’s professional baseball career ended.

Subsequently, Hargrave’s name appeared in connection with various endeavors. It was the story of many former players who tried to stay connected to the game but were also seeking a way to support themselves and their families. An article in The Sporting News in 1939 described him as manager of the Cincinnati team in a newly-formed softball league called the National Professional Indoor Baseball League, where Tris Speaker was league president.46 The league folded in a few months due to poor planning and dismal attendance.47 Thereafter Hargrave opened a tavern, Hargrave’s Hammond Tavern in Cincinnati.48 Still later he managed a semi-pro baseball team in Middletown, Ohio.49

During World War II, Hargrave worked at a Cincinnati defense plant, while his wife Hester ran the tavern “until it could be sold.”50 Eventually wartime food shortages led to sale of the tavern.51 Hargrave later went to work for the Powell Valve Co. Plant No. 2 in Cincinnati, eventually becoming a supervisor.52

In the early 1950s Hargrave reminisced about his career and baseball. He thought “catching is the best job in baseball. . . . You’re in on every play. If you like to play baseball, what more could you ask? You last longer too. There used to be a lot of good catchers but not so many any more.” His remaining connections with the game rested at the amateur or semi-pro level. “If some kid’s playing I know. I seldom go out to see the Reds. I can’t sit still long enough. I still want to get in every play and it makes me nervous.”53 Asked about his career, Hargrave was proud of his hitting, “Well if we didn’t hit .300 we didn’t feel right.” The interview ended with Hargrave telling the reporter, “Just remember I could hit.”

Eugene “Bubbles” Hargrave died in Cincinnati on February 23, 1969, at age 76 from the effects of a cerebral hemorrhage. He was the vanguard for a series of standout Reds’ hitting catchers like Lombardi, Smoky Burgess and Johnny Bench.54 Not bad for a young man whose father wanted him to get into the upholstery business.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Joel Barnhart and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 121st Ohio Infantry, http://www.ohiocivilwar.com/cw121.html

2 Robert A. Hargrave, https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=51022677&ref=acom and Harry H. Harper, ( – 1943) Find A Grave Memorial. https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=37687018.

3 Obituaries: Eugene (Bubbles) Hargrave, The Sporting News, March 8, 1969, 45.

4 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, “Top 100 Teams: 1920 St. Paul Saints,” http://www.milb.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=6

5 Sport Reminiscences Stories, The Cincinnati Enquirer, November 21, 1920, 3

6 Ancestry.com, http://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=60281&h=2267478&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=Olw55&_phstart=successSource and https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=18793395

7 Obituaries, Eugene (Bubbles) Hargrave.

8 Weiss and Wright, “Top 100 Teams: 1920 St. Paul Saints.”

9 Obituaries, Eugene (Bubbles) Hargrave.

10 “Baseball All Sorts, The Cincinnati Enquirer, April 10, 1921, 23.

11 Lombardi was posthumously inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1986.

12 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 422.

13 “…still a great batter and possesses a strong arm,” Even after his major league career was over, his throwing ability was still lauded as being effective, Irvin Rudick, “Millers Need Pitchers Only To Complete Team,” The Sporting News, February 5, 1931, 3.

14 J. E. O’Phelan, December 27, 1928, untitled article, unknown publication in Hargrave’s Hall of Fame file.

15 Obituaries: Eugene (Bubbles) Hargrave.

16 Thomas S. Rice, “Hargrave Put Out of Red Lineup With Broken Hand; Rain Keeps Superbas Idle,” unknown, undated publication in Hargrave’s Hall of Fame file.

17 Jack Ryder, “Cincinnati’s Patched-Up Team Goes Well Till Final Inning, The Cincinnati Enquirer, April 27, 1925, 12.

18 Hermann to Hargrave, January 8, 1926, Hargrave Hall of Fame file.

19 Hargrave to Hermann, January 18, 1926, Hargrave Hall of Fame file.

20 Hermann to Hargrave, January 20, 1926, Hargrave Hall of Fame file.

21 Hargrave to Hermann, January 28, 1926, Hargrave Hall of Fame file.

22 Hermann to Hargrave, February 8, 1926, Hargrave Hall of Fame file.

23 Hargrave to Hermann February 10, 1926, Hermann to Hargrave, February 12, 1926.

24 Tom Swope, “No Standing Room With Pipp Around,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1926, 1.

25 James, Baseball Abstract, 422.

26 C. Paul Rogers III, “Rogers Hornsby. SABR BioProject, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/b5854fe4

27 Billy Evans, Billy Evans Says, “Many New Leaders,” Santa Ana Register, September 1, 1926, 16.

28 Major League Batting Averages,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, September 5, 1926, 6.

29 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract – The Classic – Completely Revised, (NY: The Free Press, 2001), 154. There was also the matter of Ty Cobb’s being acclaimed batting champion in 1914 despite appearing in only 98 contests. The sentiment that year was most likely that 1) he had already won seven batting titles, 2) he was 24 points higher than his closest competitor Eddie Collins and 3) he was Ty Cobb. # In searching for precedent, Cobb’s being awarded the 1914 title never seemed to come into play. At that time Cobb was recognized as winning seven straight titles. Years later controversy over the 1910 batting race reflected Lajoie not Cobb was the rightful winner. For more see Rick Huhn, The Chalmers Race, Ty Cobb, Napoleon Lajoie, and the Controversial 1910 Batting Title That Became a Nations Obsession, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2014)

30 Jack Ryder, “Pittsburg will oppose Reds April 12, in Opening Game,” The Cincinnati Enquirer,” December 13, 1926, 14.

31# Hargrave Entitled To Batting Crown, in Heydler’s Opinion,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, December 28, 1926.

32 These include but are not limited to Dale Alexander’s title in 1932, Debs Garms in 1940, Ernie Lombardi’s in 1942 and Bobby Avila’s title in 1954.

33 “Only Three Backstops Have Won Hitting Title,” unidentified news clipping, Hargrave Hall of Fame file. The third catcher alluded to in the title of the piece refers to Jake Stenzel. The author of the article refers to Stenzel having led the league in hitting during the 1893 season when in fact he only appeared in 60 games.

34 Since then Minnesota’s Joe Mauer became the first American League catcher to take a title, wining the first of three in 2006. San Francisco’s Buster Posey earned the honor in 2012.

35 Jack Ryder, “Ain’t Life Wonderful? – – Pipp Hargrave in Reds Fold,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, March 8, 1927, 15.

36 John Saccoman, “Garry Herrmann,” SABR BioProject, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/d72a4b39

37 Dewey and Acocella, 199.

38 “Kelly’s Contract a Plague to Cincinnati,” The Sporting News, February 9, 1928.

39 Redlegs Refused to Trade Hargrave and Hughie Critz For Hornsby, Says McGraw,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, January 13, 1928, 13.

40 “Welcomes Return to Minor League,” undated article and unidentified publication, Hargrave Hall of Fame file.

41 Steve Steinberg, “Bob Connery,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/f15fa49e.

42 Ibid and B. G. W. “McCarthy Starts Yankee Shakeup; Bengough Let Out,” undated article and unidentified publication, Hargrave Hall of Fame file.

43 Daley, “McCarthy Starts Yankee Shakeup.”

44 Jack Ryder, “As Jack Ryder Sees It,” The Enquirer, February 8, 1933, 12.

45 “Raiders Await Cardinals Action,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1934, 7.

46 “Observation Tower and Pottery Plant Cincy Meccas For Ladies,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1939, 2.

47 https://miltonhooper.com/2017/02/10/friday-flashback-national-professional-indoor-baseball-league/ and Timothy N. Gay, Tris Speaker: The Rough and Tough Life of A Baseball legend,” (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), 265-266.

48 “Cincinnati Doubts Wilson-Cub Report,” The Sporting News, November 14, 1940, 3.

49 ,Various untitled clips from Hargrave Hall of Fame file

50 “In The Service, The Sporting News, January 28, 1943, 9.

51 “Bubble Hargrave Still Itches to Get Into Every Play; Can’t Sit Through Game, undated @ 1952, Cincinnati Post, from Hargrave Hall of Fame file.

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid.

54 Bench, Burgess, Hargrave, and Lombardi are in the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame.

Full Name

Eugene Franklin Hargrave

Born

July 15, 1892 at New Haven, IN (USA)

Died

February 23, 1969 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.