June 6, 1894: Pirates crush Beaneaters 27-11 at Congress Street Grounds

Less than one calendar year since winning the National League pennant, the 1894 Boston Beaneaters had been dealing with a couple of issues. The team was playing well through the beginning of June, almost exactly as well as they had been playing at that point in the prior season, but things were slightly different this time around. The clubs from Baltimore, Pittsburg, and Cleveland were sitting higher in the NL standings on June 6, with Philadelphia and Brooklyn right below.

Less than one calendar year since winning the National League pennant, the 1894 Boston Beaneaters had been dealing with a couple of issues. The team was playing well through the beginning of June, almost exactly as well as they had been playing at that point in the prior season, but things were slightly different this time around. The clubs from Baltimore, Pittsburg, and Cleveland were sitting higher in the NL standings on June 6, with Philadelphia and Brooklyn right below.

This provided a contrast to June 6, 1893, when only Pittsburg was ahead, and third and fourth position were a few games back. Aside from having lost a competitive step to some opponents since the previous year, the Beaneaters had to deal with the literal loss of a major asset: their ballpark. During a game against Baltimore in early May, a small fire that had begun under the bleachers at the iconic South End Grounds escalated into a full-scale conflagration.1 In what was eventually dubbed “The Great Roxbury Fire,” flames had quickly turned the ballpark (and many nearby buildings) into ashes and rubble.

The team was rendered homeless, and needed somewhere to play while its place was being rebuilt, so it took up temporary residence at the Congress Street Grounds. Congress Street had been the Players’ League, then American Association teams home in 1890 and 1891, but since 1891 it had been used only intermittently for baseball, and only on a minor-league level. Presenting what seemed an indication of either neglect or as a general insight into the struggles of nineteenth-century ballpark maintenance, one writer described the park’s field simply as “rough.”2 Slightly more expansive than the South End Grounds in some ways,3 Congress Street’s dimensions held one eye-catching exception: The left-field fence was about 125 feet beyond third base, or just 250 feet from home plate.4 One reporter believed that most home runs hit there “would be easy outs on any other grounds in the country.”5 The quirk in distance may have aided Bobby Lowe in becoming the first major leaguer to hit four home runs in one game. It may not have been the preferable stadium to play at, but the team did hold a 9-2 record there.

It was here that the Pittsburg Pirates came for a three-game series from June 4 to 6.

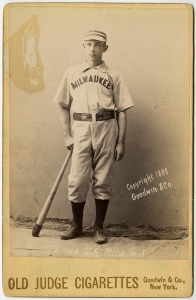

Pittsburg’s prior season had been its best yet in the National League. Surviving a rough stretch during June, the Pirates set team records for total hits, total runs, and, more importantly, total wins. They finished the year as runners-up, five games behind Boston. Going into the 1894 season, there was a great deal of optimism among the Pirates that 1894 would be their year to attain the pennant.6 After an inconsistent beginning of the season, the team reached first place by late May. The Pirates were in a three-way tie for first with Baltimore and Cleveland after games of June 2, but after splitting the first two games of the Boston series, they fell back to second, tied with the Spiders.

For the rubber match between the clubs on the 6th, Boston manager Frank Selee gave the pitching duties to a young, green southpaw named Henry Lampe. A small amount of relief work against Baltimore just before the Roxbury disaster was the extent of Lampe’s NL experience. About 2,000 fans showed up to witness what would be his first start.7

A scoreless first inning was followed by a burst of runs in the second for both sides. Boston started by logging two scores through the contributions of a walk to Billy Nash and singles by Jimmy Bannon and Charlie Ganzel. Pittsburg’s counter in the bottom of the inning was the only home run hit that season by Connie Mack, a hit that scored three runs after it flew over the left-field fence.8 Boston’s third-inning response comprised a double by Hugh Duffy and a single by Tommy McCarthy, which evened the score at 3-3.

Pittsburg’s bottom of the second inning was but a slight warmup for what happened in their half of the third. It began well for Boston, as Lampe struck out the first batter he faced, Jake Beckley. However, the next batter, Jake Stenzel, hit a home run beyond left field. After that, Denny Lyons legged out a double, and he was followed by singles by Jack Glasscock and Louis Bierbauer, the latter scoring Lyons. Lampe bested Mack by forcing him to fly out to McCarthy.

With two outs, a crucial opportunity presented itself for Boston to end the inning while keeping the damage to a minimum. Lampe’s pitching nemesis that day, Tom Colcolough, hit a grounder toward Herman Long, but when Long attempted to field the ball, it “bounded badly away,” and all runners reached base safely.9 Frank Scheibeck contributed to Pittsburg’s effort with a single, driving in Bierbauer. Patsy Donovan then hit a ball in the direction of Bobby Lowe. Lowe was another fielder having an off day, as he mishandled the ball and failed to get Donovan out, allowing Colcolough to score. Tim Murnane in the Boston Globe criticized the unfortunate defensive duo in the next day’s recap, saying, “Long and Lowe are fielding about as well as some of the glass arm boys are pitching.”10

Beckley’s double brought in Scheibeck and Donovan. Then Stenzel brought Beckley and himself back to the dugout with his second home run of the inning, increasing Pittsburg’s lead to 12-3. Lyons followed by hitting a home run to nearly the same spot beyond left field as Stenzel’s.

Another chance to end the inning came and went for Boston when Glasscock hit a grounder at Tommy Tucker, Tucker’s throw to first was fumbled by the embattled Lampe, and the runner was called safe. Bierbauer caused further consternation to the home fans as he hit his team’s fourth home run of the inning (also to left field). By the time Mack flied out to end the inning, Pittsburg held a 15-3 lead.

At this point, Selee had seen far too much of his young pitcher’s abilities. The fans likely agreed; they gave Lampe an “ovation” during his at-bat in the fourth, which one can only figure was of the mock cheer variety.11 In the bottom of the fourth, Tom Smith replaced Lampe. Smith was making his big-league debut. It showed. In the fourth inning, Pittsburg logged nine more runs through a variety of methods: four walks, one hit batsman, one single, two doubles, an error by Long, and another home run over the left-field fence (Scheibeck’s second and last of a 390-game major-league career).

Once the fourth inning ended, the pace of scoring slowed down … somewhat. Pittsburg mustered only three additional runs for the remainder of the game. Meanwhile, Boston logged a bevy in the fifth (a Lowe homer over the left-field fence), sixth, and ninth innings off Colcolough. However, it wasn’t enough to come close to Pittsburg’s total.

In the end, the 27-11 final score was brought about by a number of key factors. The strong offense of the visitors, the poor fielding of the home team, the novice pitchers, and the ballpark’s unique field dimensions all played roles in the drubbing that took place. The Globe‘s story on the game wondered why Selee didn’t opt for one of his team’s three capable pitchers who sat on the bench with better (or in this case, some kind of) experience.

Pittsburg’s seven home runs in a game weren’t matched again by the franchise until 1947, when the team was led by the power numbers of Ralph Kiner and Hank Greenberg.12 Pitcher Tom Smith played in one more Beaneaters game before being released on June 20. As for Henry Lampe, called by Murnane “in a class by himself, one of the very weakest men ever presented in a league game,” his stint with the team was over.13 He was released the day after the game.

The next few years saw both Lampe and Smith return to the major leagues with various clubs, but they toiled mostly in the minors. Coincidentally, once their ballplaying careers were over, they each became Boston city policeman.14 As for the Congress Street Grounds and its abbreviated dimensions, the Beaneaters’ tenure there lasted two more weeks. During the 27 games they played there, teams hit a total of 86 home runs, including a game-winning, send-off blast by Hugh Duffy on June 20.15 After a 23-game road trip that wrapped up in the middle of July, the team moved back to a rebuilt South End Grounds.

Sources

In addition to the sources in the notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com, retrosheet.org, and sabr.org.

Notes

1 sabr.org/gamesproj/game/may-15-1894-it-was-hot-game-sure-enough.

2 T.H. Murnane, “Lampe Goes Out,” Boston Globe, June 7, 1894: 3.

3 Robert D. Ross, The Great Baseball Revolt: The Rise and Fall of the 1890 Players League (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016), 130.

4 “Base Ball Notes,” Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph, June 6, 1894; Philip J. Lowry. Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Co, 2006), 25.

5 “Diamond Flashes,” Baltimore Sun, June 20, 1894, cited in Richard Tourangeau, “Remembering the Congress Street Grounds,” The National Pastime, 2004: 78.

6 Norman L. Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 101-102.

7 “Was Simply Awful,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, June 7, 1894.

8 Tourangeau, 76.

9 Murnane.

10 Ibid.

11 “Charleston’s Boy,” Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph, June 6, 1894.

12 baseball-almanac.com/box-scores/boxscore.php?boxid=194708160PIT.

13 Murnane.

14 Tourangeau, 76.

Additional Stats

Pittsburg Pirates 27

Boston Beaneaters 11

Congress Street Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.