June 8, 1934: Flying Reds, Public Enemies, and Baseball

Times were tough in June 1934. It was in the midst of the Great Depression. A Dust Bowl drought ravished the Midwest during one of the hottest summers on record. Rogue bank robbers pervaded the heartland. But with the World’s Fair under way on the lakefront, Chicago was a happening place to be. A place where one could revel in the hoopla or sink into anonymity.

Times were tough in June 1934. It was in the midst of the Great Depression. A Dust Bowl drought ravished the Midwest during one of the hottest summers on record. Rogue bank robbers pervaded the heartland. But with the World’s Fair under way on the lakefront, Chicago was a happening place to be. A place where one could revel in the hoopla or sink into anonymity.

The Chicago Cubs were scheduled to begin a 19-game homestand with a Friday afternoon game against the Cincinnati Reds on June 8. Friday meant it was ladies day at Wrigley Field.1 Women over 16 years old were admitted for free and free was attractive in the thin times of the ’30s. The Chicago Tribune estimated that “12,000 noisy women guests and 6,000 who paid” were in attendance.2

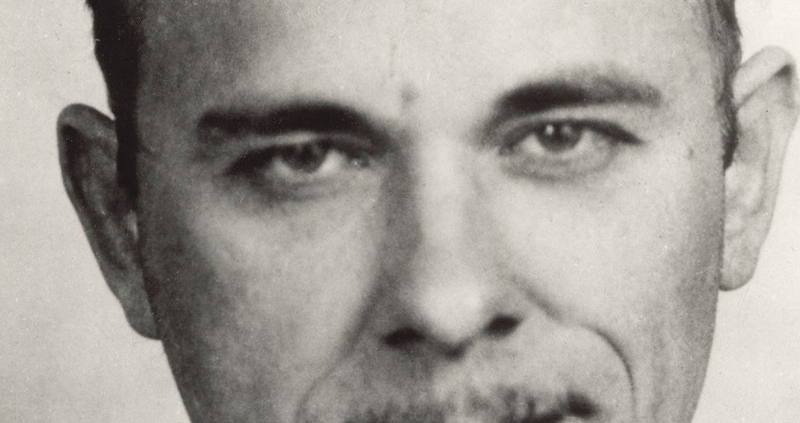

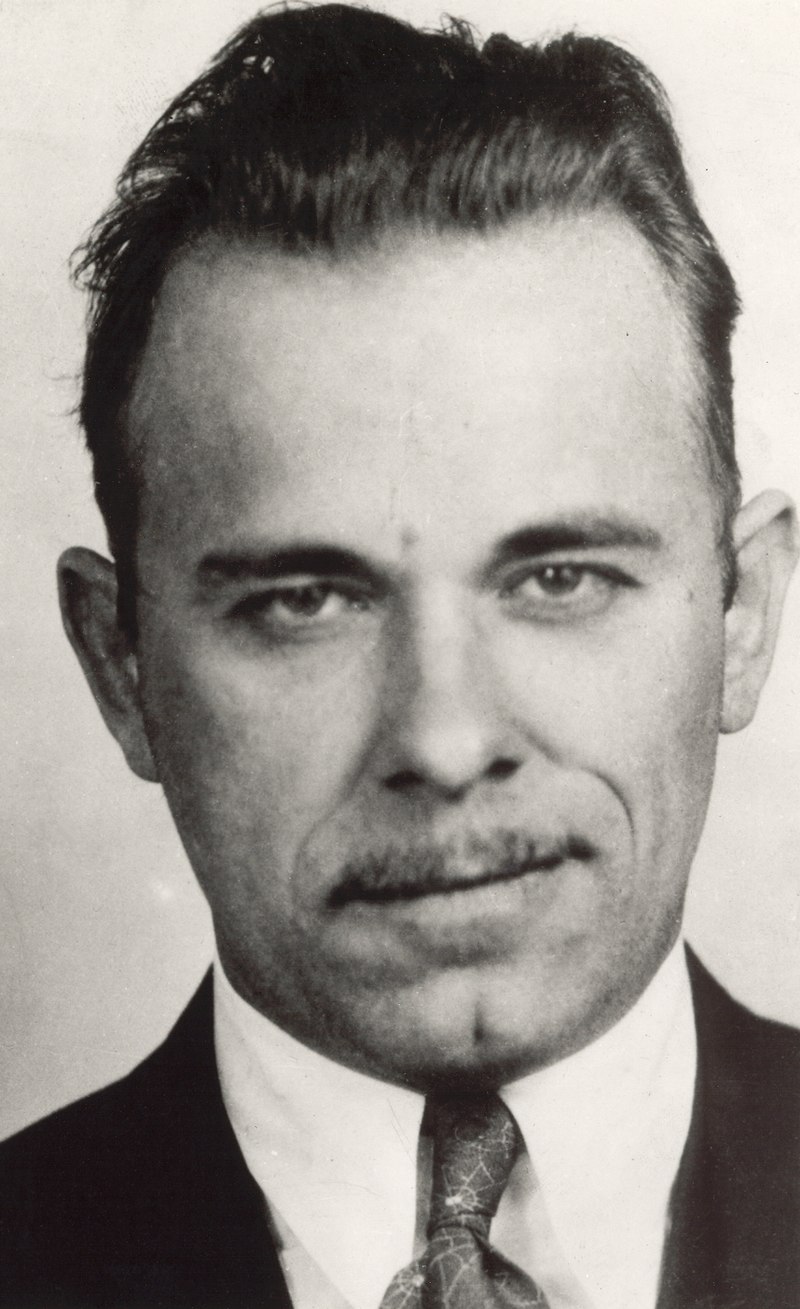

One of those who paid – likely with stolen currency – was a notorious bank robber, outlaw, and soon-to-be FBI’s Public Enemy Number 1. John Dillinger was hiding out on the North Side of Chicago that sultry summer and was an ardent Cubs fan. He was reputed to be an above-average baseball player before he turned to a life of crime.3

Perhaps Dillinger was trying to test whether recent plastic surgery sufficiently altered his appearance to help him maintain his anonymity. Maybe he just wanted to attend a ballgame where there were “two girls for every boy.”4 Whatever the motive, Dillinger made his way to at least a couple of Cubs games that hot summer. This was one of them, though it is likely that he left early when he was tipped off that members of law enforcement were also in attendance.

About a month and a half later, on July 22, Dillinger met his demise at the hands of FBI agents outside the Biograph Theater, about a mile and a half south of Wrigley Field.

As for June 8, going into the day, the Cubs had a 29-18 record and were in the thick of a four-team pennant race. Along with the Pirates and Cardinals, they were chasing the league-leading Giants.

The Reds finished dead last in the National League from 1931 through 1933 and were again at the bottom of the heap, well on their way to a fourth straight season in the cellar with just nine wins in their first 41 games.

The Cubs had won 1-0 in St. Louis a day earlier. Most likely, they returned home after that game on a late-night train, as was the custom for major-league teams in 1934.

But the Reds did something different – and their journey to Chicago heralded the future of baseball and all of America’s major sports. Cincinnati became the first team to utilize airplane travel to get to an away game.5

Hot and dusty train travel in the midst of the record heat wave surely made a team get weary, so the Reds chartered two American Airlines Ford Tri-Motors to counteract the heat of rail travel.6 As the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum put it, “General Manager Larry McPhail believed that the quicker air travel would give the players more rest between games.”7

Not every player opted to fly. There was trepidation since air travel was still eschewed by many. On a Thursday evening, all but six of the Reds (whom the Cincinnati Enquirer hailed as “a smart group of fellows”) took the 6:15 flight from Cincinnati slated to arrive in Chicago at 8:30 P.M.8 The others took the midnight train to Chicago.

It was a sweltering 91 degrees for the first pitch at 3:00 P.M. as the sun approached its western descent, making play in right field a blinding challenge.9 Just two umpires officiated the contest (the norm at the time) and there were no ivy-covered outfield walls at Wrigley Field. This was 1934.

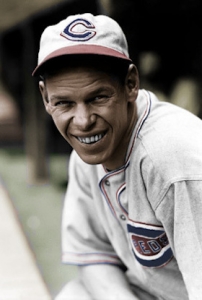

On the hill for the Cubs was Big Bill Lee in his rookie season for the North Siders.10 His opponent for the Reds was Si Johnson, an inning-eating journeyman from nearby Ottawa, Illinois.11

The Cubs survived a two-hit Reds first inning and came to the plate in the home half of the inning before an enthusiastic crowd.

Billy Herman led off with a single to center field. Two outs later, lefty Babe Herman launched a home-run rocket to deep right field for a 2-0 lead.12 Kiki Cuyler followed with a double to right field but was cut down trying to stretch it to a triple, ending the inning. It wasn’t the only basepath blunder for the Cubs that day.

The Reds broke through in the third, scoring a run to cut Chicago’s lead to 2-1. Mark Koenig hit a one-out single to center field and reached third on Chick Hafey’s double to left. Jim Bottomley grounded to second base to drive in Koenig.

Scoreless innings ensued until the sixth. Lee was more or less rolling to that point, allowing one run, scattering four hits, striking out three, and inducing eight groundouts. “In the sixth, however, his cunning vanished and the Reds were quick to prove they noticed the change.”13

Hafey singled to left to start the inning and continued to second when left fielder Chuck Klein fumbled the ball.14 Bottomley flied out to Cuyler in center for the first out, but Harlin Pool drew a walk. Adam Comorosky doubled to left to score Hafey; Pool moved to third. Gordon Slade singled up the middle, scoring Pool and Comorosky. When the dust settled, the Reds had a three-run inning and a 4-2 advantage.

The Cubs struck back with a run in their half of the sixth. Babe Herman doubled to left field with one out. Cuyler grounded a single to deep short; when Koenig threw the ball into the Cincinnati dugout for an error, Herman scored and Cuyler took second.15 Cuyler represented the tying run, but Johnson retired Gabby Hartnett and Billy Jurges to strand him on second base.

Chicago threatened again in the seventh. Dolph Camilli led off with a single to center, advanced to second on a sacrifice, and reached third on a grounder to second. He seemed destined to score when Woody English hit a smash between first and second. But Bottomley robbed English of a hit, diving to catch the ball and flipping it to Johnson covering first for the final out.16

Neither team scored again. In fact, neither team even tallied a hit in the eighth or ninth inning, as Johnson closed out the Cubs for his third win of 1934 against eight defeats. The time of the game was 1:46.

The Reds recorded only their 10th win of the season. Was their fortune a product of arriving early by air in Chicago? We can never be certain. But it makes for a solid circumstantial case. On the field, the Reds did seem refreshed by an early air arrival.

The Cubs, by contrast, looked sleepy on the basepaths with blunders in each of the first four innings. “Altogether, you would term their base running slightly stupid,” the Chicago Tribune asserted.17

In the first, Cuyler was cut down trying to stretch a double to a triple. An inning later, Billy Jurges reached first on a bunt single but was caught napping and picked off by a snap throw from catcher Ernie Lombardi to Bottomley.

In the third inning, Billy Herman led off with a single to right field, “but erred in thinking it was a double”; Pool threw him out at second base.18 In the fourth, Babe Herman led off with a double and advanced to third on Cuyler’s sacrifice. After an intentional walk to Hartnett, Jurges hit a grounder to first base. Herman was retired on Bottomley’s throw to Lombardi – “killed off trying to get home from third when the chances were about 50-1 against him.”19

The Chicago Tribune noted that two of the Cubs’ erased baserunners “were cut down trying to sneak an extra base on fluke hits caused by Pool’s trouble with fly balls.”20 Pool played right field and apparently “lost” two balls in that sinking sun. Or was he crafty? Pool recovered in time for two assists that day.

Meanwhile, the Reds appeared alert and adept in the field and scored the win that day (and the next).21 It took nearly two decades until baseball began to embrace air travel as the norm, but the genesis was this day.

Sources

The author referenced Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet.org for box scores, play-by-play information, and other pertinent data.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHN/CHN193406080.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1934/B06080CHN1934.htm

The author also accessed SABR.org, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Notes

1 https://baseballhall.org/discover/shortstops/ladies-day-promotions-gave-women-the-chance-to-cheer.

Ladies day was a big attraction after being introduced to Wrigley Field by Bill Veeck the elder. A ticket stub from May 9 in the Baseball Hall of Fame confirms the deal. “This ticket will ADMIT ONE WOMAN sixteen years of age or older to WRIGLEY FIELD” and adds NOT GOOD IF PRESENTED BY MAN OR BOY.”

2 Irving Vaughan. “Reds Beat Cubs, 4-3: Bunch Hits Off Lee.” Chicago Tribune, June 9, 1934: 17.

3 Frank Jackson. “The Ultimate Die-Hard Cubs Fan.” The Hardball Times, February 8, 2018. There are several references to John “Jackrabbit” Dillinger’s baseball prowess, even to the extent of his being transferred to the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, Indiana, because their team needed a better shortstop. This link is one of the more comprehensive articles on the subject: https://tht.fangraphs.com/the-ultimate-die-hard-cubs-fan/.

4 A nod to a Jan and Dean lyric from the 1963 song “Surf City.”

5 “Notes of the Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 8, 1934: 19. “It was the first trip of the kind ever taken by a National League club. … The team went in two large American Airlines cabin planes hoping always for the best.”

6 “With Bob Newhall broadcaster on station WLW Cincinnati on the ground and Red Barber announcer in the air Cincinnati Reds fans were kept informed of the first air trip ever … via a portable short-wave radio transmitter.” “On the Radio,: The Sporting News, June 21, 1934: 8.

7 “On June 8, 1934, nineteen members of the Reds boarded two American Airlines Ford Tri-Motors for a three-game series against the Chicago Cubs. (The Tri-Motors could carry ten to twelve passengers.) Six players opted to travel via train. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/fly-ball.

8 “Notes of the Game.”

9 “Temperatures in Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, June 9, 1934: 1.

10 Lee started 297 career games for the Cubs, completed 153 of them, and garnered 139 wins before retiring in 1947.

11 Johnson pitched for half of the original eight National League teams in his 17 seasons and lost more games than he won (career record 101-165).

12 The Cubs lineup featured two Hermans, Billy and Babe. Nicknames flourished in those times. Floyd Caves Herman was known as Babe Herman. William Jennings Bryan Herman was simply known as Billy.

13 Vaughan, “Reds Beat Cubs, 4-3.”

14 Vaughan, “Reds Beat Cubs, 4-3.”

15 Vaughan, “Reds Beat Cubs, 4-3.”

16 Vaughan, “Reds Beat Cubs, 4-3.”

17 Vaughan, “Reds Beat Cubs, 4-3.”

18 Vaughan, “Reds Beat Cubs, 4-3.”

19 Vaughan, “Reds Beat Cubs, 4-3.”

20 Vaughan, “Reds Beat Cubs, 4-3.”

21 “MacPhail Starts Something,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1934: 1. “The Pacific Coasters have long envisioned (transporting baseball teams by airplane) as an offspring of their desire for major league membership.” Air travel was validated that day and California celebrated, since their wish was to lure a team to the West Coast. But fruition of that dream was still 23 years away. Progress often is a slow-moving train.

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Reds 4

Chicago Cubs 3

Wrigley Field

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.