May 18, 1875: Boston rivalry with Hartford heats up in Red Stockings’ win

In the 1870s it was Hartford, not New York, that was Boston’s biggest diamond rival. As with the Yankees-Red Sox rivalry of recent vintage, a dislike existed between the Hartford and Boston clubs and charges of buying the pennant were alleged against each. The pinnacle of this rivalry occurred on May 18, 1875, when the Red Stockings and Dark Blues entered the game with perfect records. Hartford had 12 wins in as many tries, while Boston was even better, with 16 wins against no losses.

In the 1870s it was Hartford, not New York, that was Boston’s biggest diamond rival. As with the Yankees-Red Sox rivalry of recent vintage, a dislike existed between the Hartford and Boston clubs and charges of buying the pennant were alleged against each. The pinnacle of this rivalry occurred on May 18, 1875, when the Red Stockings and Dark Blues entered the game with perfect records. Hartford had 12 wins in as many tries, while Boston was even better, with 16 wins against no losses.

Boston’s manager, Harry Wright, wanted the game (and its accompanying big payday) to take place in Boston, but since the National Association did not have a predetermined league schedule, this was open to negotiation. Hartford’s corresponding secretary, Ben Douglas, felt the game should be played in Hartford, since the clubs’ first match, in 1874, was played in Boston. When Douglas informed the venerable Wright of his position, Wright scoffed at his boldness.1

Douglas held firm, though, and when the big day arrived, fans from all over New England and New York arrived in Hartford, not Boston. A holiday atmosphere prevailed in the city as Connecticut baseball enthusiasts believed this would be the year their team would snatch the pennant from the mighty Red Stockings, champions three years running. Nearly every business in the city displayed a team photo in the window and many stores were selling a new brand of cigars called the “Captain Bob,” featuring a picture of Hartford’s Bob Ferguson on the label. Many local factories, including the Colt gun factory, closed shop early to give employees the rare opportunity to watch a game. The enthusiasm even reached the State Capitol, where the House and Senate adjourned early so as not to miss the contest.2

Shortly after noon, Hartford streets were deserted, as those who had tickets — and many who did not — headed for the ballpark. By 2 P.M., every general-admission seat was occupied. Those too late to find seats stood in the outfield grass, corralled behind long ropes. As the mass of humanity swelled, the skimpy ropes had no hope of retaining the crowd and scores of fans spilled onto the playing field as overmatched policemen attempted in vain to push them back. Twelve thousand spectators, reportedly the largest crowd ever in New England, filled the grounds, which seated about 4,000. Most of Hartford’s most prominent residents, including Samuel Clemens, a/k/a Mark Twain, were in attendance.3 The spectators weren’t all Hartford supporters, though: More than 200 men had made the trip from Boston to see their club defend its championship.4

Polite applause greeted the ballplayers as they appeared on the field. The last to enter was Dark Blues Captain Ferguson, and the Hartford crowd welcomed him with a tremendous roar. The throng was especially partisan this day, knowing that Al Spalding had recently belittled their hometown club in a preseason newspaper interview. In the article Spalding acknowledged that Hartford had an excellent collection of talent, yet dismissed their chances of taking the pennant from his Boston team, saying, “They are an unruly set of fellows. They want more of the qualities which carry us on to glory every year. I mean brains. …”5

Boston won the coin toss and sent Hartford to bat first. Leadoff batter Doug Allison selected one of Spalding’s offerings and looped what looked to be a sure base hit over second base. Ross Barnes had other ideas, however, and to the chagrin of the huge crowd, Boston’s speedy second baseman made a fine running catch. Jack Burdock aroused the crowd with a clean single to center, but the joy was short-lived as he was immediately cut down attempting to steal second. Tom Carey followed with another base hit, but was quickly retired after failing to return promptly to his base after a foul ball. (In 1875 a foul ball became live again when it was returned to the pitcher’s hands. If a runner had not returned to his base by that time, he could be put out.6)

Hartford then sent William Arthur “Candy” Cummings, all 120 pounds of him, and his “terrible parabolic curves” to the pitcher’s box.7 George Wright found one to his liking and stroked a single. Barnes then launched a long drive to right field that was neatly run down by Tommy Bond. Connecticut’s own Jim O’Rourke followed with a single. But Cummings retired Andy Leonard on a comebacker to the box. It appeared the game would remain scoreless when Boston slugger Cal McVey tapped an easy groundball to shortstop Tom Carey. The smooth-fielding shortstop gathered the ball in cleanly and fired straight and true across the diamond. The Hartford crowd cheered loudly when first baseman Everett Mills caught the ball, believing the side was retired. But before the last “hurrah” had expired, Al Spalding was jawing with the umpire, claiming Mills had not touched first base. “Helping” the umpire was nothing new for the Boston club. Their champion status and Harry Wright’s extensive knowledge of the rules often allowed them to intimidate an unsure umpire. Sure enough, umpire Alphonse Martin, a former pitcher known as “Old Slow Ball” in his playing days, ruled McVey safe and Wright was home. The huge Hartford crowd loudly let Martin know what they thought of his decision. It was never good policy to give the powerful Red Stockings extra outs, and this occasion was no exception. Spalding followed with a base hit, plating two more runs and giving Boston a 3-0 lead.8

Two innings later, another controversial call by Martin had Hartford fans jeering again. Andy Leonard made an infield hit that scored Ross Barnes and advanced Jim O’Rourke to third. During the play, Martin quietly called time out and then just as quietly called time back in. But no one, including O’Rourke, heard him. Martin ruled O’Rourke out for failing to retouch second after time had been called. Spalding immediately reappeared on the field and the two men spent 15 minutes thumbing through the rulebook while the impatient Hartford crowd shouted, “Read it out loud!” and “Pass it around and let us all read it!” In the end, Martin let O’Rourke reoccupy second base as if nothing had happened. The mood in the stands turned ugly, especially when McVey singled to center, scoring O’Rourke and giving the champs a 5-0 lead.9

The protracted dispute seemed to rouse the Dark Blues. Doug Allison led off the fourth inning with a single. Jack Burdock then sent a slow grounder to third. Jim O’Rourke fielded it cleanly but his throw to second flew wildly into right field, leaving runners on second and third with nobody out. Carey popped out, but Cummings broke the shutout by scoring Allison with a long fly ball. Two more hits and another Boston error cut Boston’s lead to 5-3 and Hartford still had two men on base. Ev Mills then made up for his earlier miscue with a single over George Wright’s head, driving in his two mates and knotting the score, 5-5. As Jack Remsen crossed the plate with the tying run, the crowd was delirious; men tossed their hats in the air, women waved handkerchiefs, and young boys jumped about and shouted wildly.10

The score remained tied until Boston added a pair of runs in the seventh inning on consecutive hits by Jack Manning, George “Jumbo” Latham, and George Wright. Spalding had no trouble holding the lead, and when Hartford was retired in the top of the ninth, the vast crowd streamed onto the field despite the best efforts of the police. Once the field was cleared, Boston added three superfluous runs to make the final result 10-5.11

When news of the Red Stockings’ victory reached Boston, team headquarters were flooded by fans who were “nearly frantic with delight.”12 On the train ride home, the ballplayers got wind of the impending celebration and remained alert for the first signs of a welcome. At about 10 P.M., about 400 revelers, including a 20-piece German band, marched to the train station to greet their conquering heroes. The Red Stockings disembarked to loud cheers while the band serenaded them with “Hail to the Chief.” The crowd escorted the team back to its headquarters, where a large banquet was served.13

This article was originally published in “Boston’s First Nine: The 1871-75 Boston Red Stockings” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin. To read more articles from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Photo caption

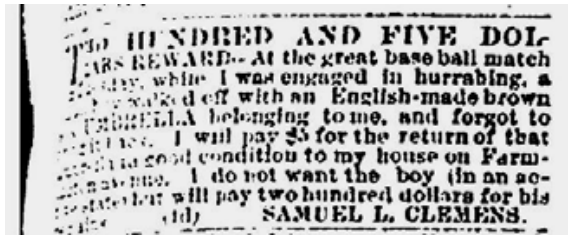

This ad from Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) appeared in the May 20, 1875 Hartford Courant, offering a $205 reward for the return of his umbrella and the remains of the boy who took it during the game.

Notes

1 Wright’s stinging reply to Douglas dated April 20, 1875: “As the champion club we consider ourselves entitled to the first game of the series on our grounds. … In arranging with you we were willing, as friends and neighbors, to comply could we mutually agree on dates, but we did not expect that it would be compulsory for us to accept dates named by you under the plea that they were ‘the only ones left.’ If that is the case they must certainly be of great value to you, particularly so when they ‘are being rapidly taken up.’ We would be sorry to deprive you of the ‘last of the lot’ to replete our stock, nor will we be compelled to accept remnants.” Harry Wright Correspondence, Albert G. Spalding Collection, New York Public Library.

2 Hartford Courant, April 21 and May 19, 1875; Meriden Daily Republican, May 18, 1875.

3 While he was at the game, Twain’s umbrella was stolen and the following classified ad appeared in the May 20 Hartford Courant: TWO HUNDRED AND FIVE DOLLARS REWARD — At the great base ball match on Tuesday, while I engaged in hurrahing, a small boy walked off with an English-made brown silk UMBRELLA belonging to me and forgot to bring it back. I will pay $5 for the return of the umbrella in good condition to my house on Farmington Avenue. I do not want the boy (in an active state) but will pay two hundred dollars for his remains. SAMUEL L. CLEMENS. Twain’s humorous ad nearly backfired on him when a local medical student reportedly had some fun at his expense. The imaginative student left one of his case studies — the corpse of a boy — on Twain’s porch, along with a note claiming the reward money. A nervous Twain was concerned he’d be suspected of murder, until the janitor of the medical college came to claim the subject and clear the author’s name. Brooklyn Eagle, August 18, 1875; Seaside Gazette (Vineyard Grove, Massachusetts), August 17, 1875.

4 Hartford Courant, May 19, 1875; Hartford Times, May 19, 1875; Chicago Tribune, May 19, 1875.

5 Arthur Bartlett, Baseball and Mr. Spalding — The History and Romance of Baseball (New York: Farrar, Straus and Young, Inc., 1951), 48.

6 Hartford Courant, May 19, 1875; New York Clipper, May 29, 1875.

7 Hartford Times, May 19, 1875; Hartford Post, May 19, 1875.

8 Ibid.

9 William Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings: A History of Baseball’s National Association, 1871-1875 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1992), 205–207; New York Clipper, May 29, 1875.

10 Hartford Courant, May 19, 1875; Boston Herald, May 19, 1875.

11 Hartford Courant, May 19, 1875.

12 Hartford Courant, May 20, 1875.

13 Boston Herald, quoted in Hartford Courant, May 20, 1875.

Additional Stats

Boston Red Stockings 10

Hartford Dark Blues 5

Hartford Base Ball Grounds

Hartford, CT

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.