Ross Barnes

“No matter how great you were once upon a time – the years go by, and men forget,” wrote W. A. Phelon in Baseball Magazine in 1915. “Ross Barnes, forty years ago, was as great as [Ty] Cobb or [Honus] Wagner ever dared to be. Had scores been kept then as now, he would have seemed incomparably marvelous.”1 One might be shocked at such a lofty judgment, or simply brush it off as empty hyperbole from a sportswriter for whom everything was better a generation or two earlier. But was it accurate?

A pioneer of baseball, the right-handed Ross Barnes was one of the best hitters over a six-year stretch (1871-1876) that the sport has ever seen. He was the undisputed master of the fair-foul hit, a speedy and innovative base stealer, and a daring second baseman with a rifle arm in an era when fielders did not wear gloves. A cornerstone of the great Boston teams in the first professional baseball league, National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (1871-1875), Barnes batted over .400 in three out of five seasons helping his club capture four consecutive championships. In the inaugural campaign of the National League the following season, Barnes topped the circuit in almost every offensive category, including hitting (.429) to lead the Chicago White Stockings to the title. Barnes’s end came quickly. Struck with a debilitating illness at the height of his career in 1877, he played only three more, mostly ineffective seasons and retired in 1881 as a shell of his former self.

Testimonials about Barnes’s accomplishments abound in the sports pages of the late 19 th and early 20th centuries. In 1887, the Chicago Tribune reported that Bob “Death to Flying Things” Ferguson, a longtime former player and respected manager in the NA and NL, regarded Barnes as the “best batter and ball player that ever lived” and also noted that the generation of players following Barnes drank too much.2 The Sporting Life, in an 1898 article, considered Barnes, along with George Wright and Cap Anson “one of the fellows who built the foundations of the game as it is played.”3 Barnes was the “king of second baseman, as well as the finest batsman and run-getter of all time” pronounced former NA ballplayer-turned-nationally-syndicated sportswriter Tim Murnane in 1903.4 Mike Scanlon, a Washington, D.C. baseball institution who wrote about the sport for 50 years beginning in the 1860s, opined in the Washington Post in 1906, “I believe [Barnes] was a greater player than [Nap] Lajoie is to-day.”5 Hall of Fame pitcher and sporting goods pioneer Al Spalding, whose transformation from a sandlotter in a Midwestern town to the era’s most acclaimed hurler was closely tied to Barnes for about a decade, named Barnes the second baseman on baseball’s all-time team in multiple issues of the Spalding Guide prior to World War I.6 A more impartial arbiter, William Connelly, writing for Baseball Magazine in 1914, selected Barnes to baseball’s third all-time team, after Nap Lajoie and Eddie Collins.7

Phelon’s observation about fading memories was prescient. Barnes’s accomplishments and contributions to the game gradually began to a fade as those with memories of him passed. By the 1950s Barnes had been consigned to a footnote in baseball history. In light of renewed interest in 19th century baseball and with the efforts of the Society for American Baseball Research, Barnes’s legacy has attracted more attention. In 2013 SABR’s Nineteenth Century Baseball Committee selected Barnes as the “Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legend.”8

Roscoe Charles Barnes was born on May 8, 1850, in Mount Morris, a small town in upstate New York, about 45 miles southwest of Rochester. For many decades well after his playing career ended, Ross Barnes was often misidentified as Roscoe Conkling Barnes. The mistake arose because of his middle initial and the name of a well-known US representative and later US senator from New York from 1867 to 1881, Roscoe Conkling. Ross Barnes’s parents were Joseph, a farmer, and Mary (Weller) Barnes, both native New Jerseyians, who married in 1832 and subsequently welcomed at least eight children into the world between 1834 and 1854 (five boys, John, Fletcher, Joseph, Ross, and Franklin; and three girls, Lucy, Sara, and Martha). According to the 1860 US Census, the family resided in Lima, about 20 miles northeast of Mount Morris. By 1865 or 1866, the Barnes clan had relocated to Rockford, a fast growing industrial city of about of about 8,000, located 90 miles west-northwest of Chicago.

During four unimaginably destructive years of civil war which claimed approximately 620,000 lives (about 1 in every 25 males), many Union and Confederate soldiers were exposed to baseball. When they returned to their respective towns across the country after the war, they brought “base ball” with them, thereby increasing its popularity. No longer just a sport played predominantly in the East, baseball was emerging as a national pastime. The New York Times described Rockford of the 1860s as “the cradle of the great American sport in the West.”9 Though it is difficult to determine when young Ross began to play baseball, by 1866 he was a member of the Pioneers, a local 16-and-under amateur team on which another famous Rockford resident, Al Spalding, also played. By late 1866 or early 1867, the Rockford Forest Citys, an adult amateur team signed both Barnes and Spalding, whose fates would be linked for the next decade.

Playing shortstop for the Forest Citys from 1867-1870, Barnes established a reputation as one of the best all-around, young players in the game. Three games deserve mention. Barnes, Spalding, and the Forest Citys gained national exposure in what baseball historian John Thorn considered among the most, if not the most important, games in baseball history.10 Rockford upset the seemingly invincible National Club of Washington, which had embarked on one of the first tours in baseball history, 29-23, on July 25, 1867 in Dexter Park, Chicago. The Forest Citys subsequently enjoyed “phenomenal success” and also toured nationally.11 On June 24, 1869, the Rockford amateurs were on the verge of handing the Cincinnati Red Stockings, the first openly professional baseball team, their first loss in a game described by the Chicago Tribune as “the most exciting and hotly contested game of base ball ever played” in Cincinnati.12 Trailing 14-12 after eight innings, Cincinnati, led by player-manager Harry Wright, his brother George, and Charlie Gould scored three runs in the ninth to win and thus preserve the first and only undefeated season in professional baseball history. Rockford avenged the loss the following season when the defeated Cincinnati 12-5 on October 15, handing the professionals one of their six losses in 74 contests.13

Harry Wright did not forget Barnes or Spalding when he was hired to form the first professional baseball team in Boston in early 1871. In addition to taking several of his own players from Cincinnati, notably his brother, Gould, and Cal McVey, as well as the club’s name, the Red Stockings, he traveled to Rockford and signed Barnes and Spalding. The core of the club that would eventually dominate the National Association was in place.

Founded on March 17, 1871 in New York City, the National Association was the first professional baseball league; however, neither Major League Baseball nor the Baseball Hall of Fame (as of 2016) considers it one. Over the course of its five-year existence, the NA was marred by franchise instability. The league consisted annually of eight to 13 teams; however, there were at least 23 different clubs, but only three, the Boston Red Stockings, New York Mutuals, and Philadelphia Athletics fielded a team for all five seasons. The league also lacked a central authority, like the National Commission (1903-1920) or its replacement, the Commissioner of Baseball, to oversee baseball and ensure its integrity. Consequently the NA was plagued by contact jumpers as well as gamblers.

Boston, considered among the favorites to win the NA’s inaugural championship, got off to a rough start, winning just seven of its first 15 games (one tie), which were often scheduled just days in advance. Signed as a second baseman, Barnes moved back to shortstop when George Wright, widely regarded the best player in the county at the time, was injured. Once Wright returned, the Bostons went on a roll, winning 13 of their last 16 to battle the Chicago White Stockings and the Philadelphia Athletics in what proved to be the only pennant race in the NA’s history. A crushing 10-8 loss to Chicago on September 29 ended Boston’s hope for a title. Though Harry and George Wright, as well as Spalding grabbed most of the attention, Barnes was arguably the most exciting offensive player in the league. The 21-year-old scored the most runs (66 in 31 games) and totaled the most bases (91). He also ranked second in extra-base hits (19), third in batting average (.401), and tied for fifth in RBIs (34).

Boston dominated the National Association over the next four years, running away with the title each year with records of 39-8, 43-16, 52-18, and 71-8. Unlike other teams, Boston benefitted from uncharacteristic continuity among its players. Barnes, George Wright, McVey, Andy Leonard, and Harry Schafer started for all four seasons; Spalding notched an unfathomable 185 of the team’s 205 victories. In 1873, Boston acquired catcher Deacon White, perhaps the best offensive and defensive catcher in the NA.

In his second season in the NA, Barnes gradually emerged from George Wright’s shadow to become the league’s most feared hitter. In this era, pitchers stood 50 feet from the mound and threw underhand; batters, known as strikers as in cricket, called for either low or high balls, and were not penalized for fouling pitches (unless they were caught). Described by William Connelly of Baseball Magazine in 1915 as a “demon with the bludgeon,”14 Barnes batted a league-high .430 and .431 in 1872 and 1873 respectively, as well as pacing the circuit in slugging percentage, extra-base hits, and total bases in both seasons; in 1873 he scored a league-record 125 runs in 60 games. After missing 19 games in 1874, yet batting .340 and finishing sixth in runs scored (the top six and eight of the top 10 run scorers were from Boston), Barnes returned in 1875 to set the NA record for hits (143) and led the league in runs (115). He owns the career record for a number of offensive categories in the NA, including batting average (.391), runs scored (459 in 265 games), doubles (101), and slugging percentage (.518), while batting primarily in the leadoff position.

What made Barnes a feared hitter? At 5-foot-8 and 145 pounds, Barnes was of average height and weight, and about the same size as George Wright. Spalding, for example, was the tallest at 6-foot-1. Barnes excelled by taking a cerebral approach to the game, augmenting his natural athletic abilities. During his career and in the few decades thereafter, Barnes was often described as a scientific hitter, for example by the New York Clipper in 1878.15 Barnes was “not of the class of chance hitters who, when they go to bat simply go in to hit the ball as hard as they can without the slightest idea where it is going,” wrote the Boston Globe. “He studied the position and made his hits accordingly.”16

As a scientific hitter, Barnes mastered the art of hitting “fair-fouls,” a legal hit during all five years of the NA and the first year of the NL. According to Peter Morris in his ground-breaking study A Game of Inches, Dickey Pearce is credited for having developed the practice in the 1860s.17 Fred Cone, a native Rockford resident who played with Barnes on the Forest Citys, and with the Boston Red Stockings in 1871, provided an excellent description of the fair-foul hit in Baseball Magazine in 1899. “The trick was to cricket the ball with a hard swing so that it would strike fair and bound off into foul territory,” said Cone. “If the ball could be cut hard down near the base line, it would get away from the fielder and roll on for two or three bases.”18 Some researchers have dismissed Barnes’s batting accomplishments, suggesting that he took advantage of a loop-hole. Bill James, for example, argued in the Historical Baseball Abstract that Barnes is not among the 125 best second basemen in the history of the sport because he was primarily a fair-foul hitter.19

A closer examination of Barnes career might suggest a different conclusion. Robert H. Schaefer, in his insightful article on fair-foul hitting in the National Pastime, provided a compelling argument that players in the 1870s did not consider a fair-foul a “second-rate means of attaining first base or that it was a cheap hit” on the contrary, “it was universally regarded as requiring exceptional finesse. Only the most highly skilled strikers were able to execute it with consistency.”20 The fair-foul was almost impossible to defend against; however, few batters were able to hit them hard like Barnes. Far from being a one-trick pony capable only of fair-foul hit, Barnes was a complete hitter who sprayed balls to all fields as attested by countless game summaries from Boston and Chicago newspapers. If anything, Barnes took advantage of defensive shifts. If the third baseman played close to the bag in an attempt to defend against the fair-foul, Barnes hit the ball in the gap between second and third base. When the National League banned the fair-foul prior to the 1877 season, few players, managers, or executives felt Barnes, widely hailed the best hitter in the sport, would suffer. “I don’t think it [new rule] will affect his average in the least,” said Charles E. Chase, vice president of the Louisville Grays. “He can bat equally well to any portion of the field,” but also added, “He undoubtedly gained many runs for his club last year by his scientific fair fouls.”21

In addition to his hitting exploits, Barnes might have been the NA’s most dangerous player on the base paths. According to Tim Murnane, who played against Barnes in both the NA and NL, Barnes “had no superior as a baserunner.”22 Barnes holds the single-season stolen base record (43 in 1873) as well as the career-record (103) in the NA. Murnane, whose 30 steals in 1875 were one better than Barnes’s 29, also noted that Barnes was the “first player to throw himself wide of the base and hold onto the bag.”23

Teammate Fred Cone claimed that Barnes’s “fielding was the cleverest ever seen.”24 Barnes played during an era when fielders did not wear gloves (they became standard equipment in the 1880s), and infielders and catchers (who wore no mask) were especially prone to injury. Fielding errors were a major part of the game. Games averaged approximately 14-16 errors during the five years of the NA; and more than two-thirds of all the runs scored were considered unearned. The second baseman was arguably the most active infielder; he covered all of the ground from second to first, short center and short right field, and second base on steal attempts. The New York Clipper lauded Barnes’s “shrewd judgment” as a fielder and considered him a “base-playing strategist” with no equal.25 Once described as the “Johnny Evers of his day,”26 Barnes teamed with George Wright to form the most formidable infield in the NA. Barnes “could cover more ground than any man I ever saw,” wrote Tim Murnane. “He had a long reach and could pick up ground balls when on the dead run from either side.”27 With his strong, whip-like throws, Barnes led second basemen in assists for four consecutive seasons (1872-1875), and in double plays three times. Perhaps most tellingly, Barnes led all second sackers in fielding percentage from 1872-1874, and again with Chicago in the inaugural season of the NL.

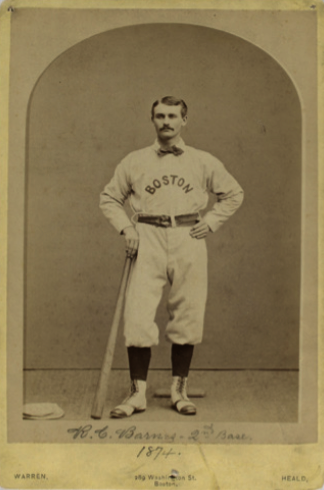

Throughout his playing career, Ross was described as honorable and a gentleman, good-looking, well-dressed, and concerned about his appearances.28 He had a medium complexion, with dark hair and dark eyes, and typically sported a fashionable moustache, often a thick walrus one. Despite his outwardly aristocratic appearance, Barnes supposedly had a prickly personality and gave the impression of a prima donna. William Ryczek, in his study on the history of the National Association, noted that Boston manager Harry Wright often used harsh words to keep Barnes in his place.29 During Boston’s four-year stranglehold on the NA championship, the club was anything but a harmonious group. According to Al Spalding, “there was a time when the whole infield wouldn’t speak to Ross Barnes.”30 The Chicago Tribune reported that for the entire 1872 season Barnes and first baseman Charlie Gould “never exchanged a word, and glanced at each other like opposing game chickens,”31 leading some to conclude that their feud led to Gould’s retirement at season’s end.32

In 1874 Boston and the Philadelphia Athletics, the most prominent baseball clubs of the NA, interrupted their season on July 16 to depart on a historic good-will trip to England to foster interest in the sport by playing exhibitions among themselves and against English cricket teams.33 Discovering little interest for baseball in Old Country, the teams finally returned stateside on September 9, and resumed play in the NA. But the mood in Boston was not as jovial as when they departed.

During Boston’s almost eight-week absence, speculation had arisen that the club might not field a team the following season. Rumors persisted through the offseason and into the 1875 campaign when the Chicago Tribune made an earth-shattering announced in mid-July that the Chicago White Stockings’ president William Hulbert had signed Barnes, Deacon White, Cal McVey, and Al Spalding.34 Boston, which had largely been spared of debilitating contract jumping, was dealt a death blow. The signings “shook the baseball world by its very centre” and were “greatest sensation in the history of baseball” wrote Harry Palmer in Outing.35 Some wondered if the “Big Four,” as they were described thereafter, would depart in midseason, but they didn’t, and led Boston to what proved to be the last title in the NA.

Hulbert’s signing of the “Big Four” was a calculated move in an effort to stack his own team in what he hoped would be a new professional league, organized and run by business men for the sake of earning profits. The result was the founding of the National League on February 2, 1876. The eight-team league consisted of six teams (Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, Hartford, St. Louis, and Mutual of New York) from the NA and two new teams (Cincinnati and Louisville). No longer was the Eastern seaboard the epicenter of the baseball world.

Playing a prearranged schedule of 66 games from late April to late September, Chicago cruised to the championship. Barnes led the league in practically every offensive category, including batting average (.429), slugging percentage (.590), runs scored (126), hits (138), doubles (21), triples (14), extra base hits (36), and total bases (190), while playing in every game. Had there been an MVP award, it would likely have been a toss-up between Barnes and Spalding who won 47 games in his final, full season.

Barnes made history on May 2 at Avenue Grounds in Cincinnati when he hit the first home run in the history of the National League in Chicago’s 15-9 defeat of the Reds. With two outs in the fifth inning, Barnes smashed what the Chicago Tribune called “the finest hit of the game, straight down the left field to the carriages for a clean home run.”36 In his next at-bat Barnes almost repeated his feat by lining one to the fences for a triple.

In the offseason, team owners engaged in a heated discussion about fair-foul hits and bunting. According to the Chicago Tribune, there were several proposals for rule changes: eliminate bunting altogether; require a batter to take a full, hard swing at the ball; ban fair-foul hitting completely; or a combination of all three.37 There is no proof that rule changes were directed at Ross Barnes. The Tribune noted that requiring batters to swing forcefully at the ball would almost certainly curtail bunting, as well as fair-foul hitting (which were often hit like a bunt); however, Ross Barnes would not be affected by such a change. Indeed the daily offered yet more proof of his overall hitting ability. “[Barnes] always hits [the fair-foul] with a full swing of the bat, and just as hard as he strikes any other kind of ball.”38 Ultimately, the fair-foul hit was banned.

A career .399 hitter over his first six seasons in professional ball (1871-1876), Barnes’s batting average dropped precipitously to .272 in 1877 leading many researchers in the latter half of the 20h century and beyond to conclude that Barnes was indeed just a fluky fair-foul hitter who was unable to adjust to the rule change. That judgment seems incorrect.

The 27-year old Barnes left the Chicago White Stockings in mid-May 1877, suffering from a mysterious illness. On May 19 the Chicago Tribune reported that “Barnes has been physically incapable of exertion; he is as weak, debilitated and worn as would be any strong man after six month’ sickness.”39 He returned to his home town of Rockford to recover, and was expected back in June.40 However as June came and went, and Barnes was unable to play, rumors also spread. The Tribune refuted claims by their rival paper, the Chicago Times, that Ross was fabricating his illness and should be released. “The slam at Ross Barnes is scandalous and utterly unfounded,” wrote the Tribune. The paper also published a telegram purportedly from Barnes, “I seldom leave the house now. I don’t feel badly, but I grow weaker every day.”41 When Barnes showed up at Chicago’s ball park, the Twenty-Third Street Grounds, on August 7 for the first time since his last game on May 17, the crowd gave him a “hearty round of applause.”42 However, “the King of the Game” could not rekindle his old magic. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that Barnes “showed the effects of sickness” upon his return;43 and subsequently, that Barnes “seemed to have lost all of his former vim, and played without energy or life.”44

SABR member Robert H. Schaefer has argued compellingly that Barnes suffered from the ague, a malaria-like chronic disease which caused fevers, chills, and debilitating muscle aches and pains.45 Contemporary newspapers reported about rumors that Barnes never fully recovered from the illness which apparently sapped his natural athleticism and speed, prematurely ending his professional baseball career after two more ineffective seasons (1879 and 1881).46

Chicago did not offer Barnes a contract for the 1878 season; however, the ball player was not yet finished with business in the Windy City. In early 1878 he became the first professional ballplayer to file a lawsuit against the club to redress a contract grievance. Barnes claimed that he was not paid for three months of his $2,500 salary when he was sick and could not play. According to the Chicago Tribune, the “case is a new one in the experience of ball clubs, and the outcome will be looked forward to with the interest of the professional ballclubs.”47 Ultimately Judge M. B. Loomis in the Cook County Courts ruled against Barnes later that year.48

Barnes was a baseball nomad in his final years as an active player. In 1878 he signed as a player-manager with the London (Ontario) Tecumseh of the International Association. Some researchers consider the IA to be the first “minor league” or even a rival to the NL. In 1879, Barnes joined his former teammates Cal McVey and Deacon White on the Cincinnati Reds. Barnes batted .266 for the fifth-place club in an eight-team league. Out of baseball the following season and reported to be a “commercial traveler for a Western wholesaler” according to the Chicago Tribune, Barnes’s career came full circle when he accepted manager Harry Wright’s offer to rejoin Boston.49 Now 31 years old, Barnes played primarily shortstop (as he had for Cincinnati). Described as “useless as a fifth leg on a horse,” Barnes batted .271 and tied Tom Burns to lead all shortstops with 52 errors while the Red Stockings finished in sixth place.50

After the 1881 season with Boston, Barnes returned to his home in Rockford. He occasionally played in amateur games with the Forest Citys, and even contemplated a few comebacks, but the most prolific hitter in the first few years of baseball never donned another uniform. In nine professional seasons, Barnes batted .360, collected 860 hits, and scored 698 runs in 499 games.

Barnes was apparently in good financial position after his playing career. The extended Barnes family was well established in Rockford. Brothers John, Fletcher, and Franklin became successful industrialists and bankers. Newspapers reports in the 1880s claimed that Ross Barnes had a net worth of $100,000, and was a successful member of the Chicago Board of Trade.51

Barnes returned to baseball in 1890 as an umpire in the newly formed Player’s League. Founded by baseball’s first union, the Brotherhood of Professional Base-Ball Players led by John Ward, it lasted only one season, but included many of the stars on the NL. Barnes soon discovered that “umpiring isn’t as pleasant as he expected it to be” and “came in for a regular kicking roast at the hands of the players.”52 The experience was a bitter one for Barnes, who felt as though he had been manipulated into becoming an umpire.53

A bachelor, Barnes spent the rest of his life in the Windy City, as well as maintaining a regular presence in Rockford.54 He was reportedly involved at one time in the hotel business and also worked as an accountant for the Peoples Gas Light and Coke Company. On May 5, 1915, Barnes died at the age of 64 in his apartment in the Hotel Wicklow on 666 N. State Street in Chicago. The cause of death was reported as both a dilation of the aorta and stomach problems.55 He was buried in his parents’ plot at Greenwood cemetery in Rockford.

According to the rules of the Baseball Hall of Fame (as of 2016), only players with a minimum of 10 years of major-league experience are eligible for induction. Barnes falls one year short. Unlike some of his teammates, Barnes was not involved in the game as a manager, owner, or organizational pioneer which would allow him to be considered for induction as a non-player. For example, teammate Harry Wright played only four full seasons (all in the NA), but is considered the father of professional baseball by many; and Al Spalding pitched only six full seasons, yet went on to found a sporting goods empire, and served as an executive of the Chicago White Stockings. There have been efforts, led by social media sites like Facebook, urging the Hall of Fame to reconsider its rules in light of Barnes’s contributions to baseball in its earliest professional phase. Perhaps one day, Ross Barnes, will join his teammates, the Wright Brothers and Spalding, and those to whom he was so favorably compared, such as Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Nap Lajoie, and Eddie Collins, and be enshrined with baseball’s best in the Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 W. A. Phelon, “The Month’s Parade,” Baseball Magazine, April 15, 1915: 123.

2 Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1887: 13.

3 The Sporting Life, May 23, 1898: 14.

4 Tim Murnane (1903) quoted from “One of the Greatest Players of All Time Was ‘Ross’ Barnes,” Boston Globe, February 6, 1915: 5.

5 ”Old Fans Recall Days of Nationals Triumph,” Washington Post, June 10, 1906: 2.

6 See for example, Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide. 1907. Henry Chadwick, ed. (New York: American Sports Publishing, 1907).

7 William Connelly, “The Greatest Baseball Team of All History,” Baseball Magazine, May, 1914.

8 “SABR 43: Ross Barnes Selected as Overlooked 19 th Century Baseball Legend for 2003,” SABR.org. http://sabr.org/latest/sabr-43-ross-barnes-selected-overlooked-19th-century-baseball-legend-2013.

9 “Diamond Find Veterans,” New York Times, April 12, 1896: 3.

10 John Thorn, “July 25, 1867: The most important game in baseball history?,” SABR.org. http://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/july-25-1867-most-important-game-baseball-history. And “Base Ball. The Great Tournament. Opening Game Between the Nationals and Forest City Club – A Close and Exciting Outcome,” Chicago Tribune, July 26, 1867: 4.

11 “Diamond Find Veterans,” New York Times, April 12, 1896: 3.

12 “Base Ball. Rockford Boys at Cincinnati,” Chicago Tribune, July 25, 1869:1

13 “The Sporting World. The Rockford Amateurs Defeat the Cincinnati Professionals,” Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1870: 3.

14 Connelly.

15 “No. 4 – Roscoe C. Barnes, Second-Baseman,” New York Clipper, 1878. [Undated article].

16 “One of the Greatest Players of All Time Was ‘Ross’ Barnes,” Boston Globe, February 6, 1915: 5.

17 Peter Morris. A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations that Shaped the Game (Guilford, Connecticut: Ivan R. Dee, 2006).

18 E.G. Westlake, “Baseball Thirty Years Ago,” Great Bend (Kansas) Weekly Tribune, July 21, 1899: 6.

19 Bill James, New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Free Press, 2001), 533.

20 Robert H. Schaefer, “The Lost Art of Fair-Foul Hitting,” The National Pastime, Number 19, 1999: 5.

21 Chicago Tribune, March 4, 1877: 7.

22 Tim Murnane (1903) quoted from “One of the Greatest Players of All Time Was ‘Ross’ Barnes,” Boston Globe, February 6, 1915: 5.

23 Ibid.

24 The Sporting Life, May 23, 1898: 14.

25 “No. 4 – Roscoe C. Barnes, Second-Baseman,” New York Clipper, 1878. [Undated article].

26 “Barnes was the Johnny Evers of his day,” Arizona (Phoenix) Republic, July 28, 1911: 12.

27 Tim Murnane (1903) quoted from “One of the Greatest Players of All Time Was ‘Ross’ Barnes,” Boston Globe, February 6, 1915: 5.

28 Sam Crane “Sam Crane Writes Series of Stories on Fifty Greatest Ball Players in History.” Undated article. Player’s Hall of Fame file.

29 William J. Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings. A History of Baseball’s National Association, 1871-1875. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1992), 26.

30 The Sporting Life, January 15, 1898: 7.

31 Chicago Tribune, January 19, 1879: 12.

32 Ryczek, 26.

33 John W. Bauer, “Summer 1874: New game in the Old World. US teams tour England,” SABR.org, http://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/summer-1874-new-game-old-country-us-teams-tour-england.

34 “Base Ball. The Nine Next Year,” Chicago Tribune, July 20, 1875: 5.

35 Harry Palmer, “America’s National Game,” Outing, July 1888,:354.

36 “Sporting News. Fourth Game and Victory of the Chicago White Stockings,” Chicago Tribune, May 3, 1876: 5.

37 “Base-Ball. More About the New Rules,” Chicago Tribune, November 26, 1876: 7.

38 Ibid.

39 “Base-Ball,” Chicago Tribune, May 19, 1877: 2.

40 “Base Ball Topics,” The Times (Philadelphia), May 31, 1877: 2.

41 Chicago Tribune, July 22, 1877: 7.

42 “The Six league Clubs Engage in Championship Contests,” Chicago Tribune, August 8, 1877: 5.

43 Cincinnati Enquirer, August 29, 1877: 7.

44 Cincinnati Enquirer, October 8, 1877: 5.

45 Robert H. Schaefer, “The Lost Art of Fair-Foul Hitting,” The National Pastime, Number 19, 1999: 6.

46 See Cincinnati Enquirer, January 11, 1879: 6 and Chicago Tribune, June 15, 1879: 7.

47 Chicago Tribune, November 10, 1878: 7.

48 Ibid.

49 Chicago Tribune, December 5, 1880: 7.

50 Cincinnati Enquirer, October 2, 1881: 9.

51 Pittsburgh Daily Post, April 20, 1887: 6 and Pittsburgh Dispatch, February 1, 1889: 6.

52 Sporting Life, May 3, 1890:10.

53 Sporting Life, January 3, 1891: 2.

54 It appears as though Ross Barnes was married for 14 months. According the marriage indexes in Cook County, Illinois, Barnes married Ellen F. Welsh on August 14, 1900. The couple was granted a divorce in October 1901. “Mrs. Barnes is divorced,” Rockford Morning Star, October 22, 1901.

55 Sporting Life, February 13, 1915 and March 6, 1915.

Full Name

Charles Roscoe Barnes

Born

May 8, 1850 at Mount Morris, NY (USA)

Died

February 5, 1915 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.