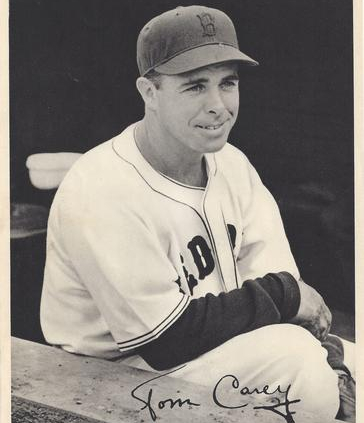

Tom Carey

A “flashy infielder” known for his fancy defensive work rather than his bat, Tom Carey played eight major-league seasons with the St. Louis Browns and the Boston Red Sox, retiring with a .275 batting average, 2 home runs, and a .972 fielding percentage in 466 games. According to St. Louis sportswriter J. Roy Stockton, the infielder was “agile as a cat, with nimble fingers, an accurate arm and the ability to throw quickly from any position.”

A “flashy infielder” known for his fancy defensive work rather than his bat, Tom Carey played eight major-league seasons with the St. Louis Browns and the Boston Red Sox, retiring with a .275 batting average, 2 home runs, and a .972 fielding percentage in 466 games. According to St. Louis sportswriter J. Roy Stockton, the infielder was “agile as a cat, with nimble fingers, an accurate arm and the ability to throw quickly from any position.”

Thomas Francis Aloysius Carey was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, on October 11, 1906. Carey understated his age during his playing career, shaving two years by claiming he was born in 1908 rather than 1906. (1) According to the 1910 Census, his father, Patrick, was a laborer who emigrated from Ireland to the United States in 1889, a year after Tom’s mother, Mary, arrived from Ireland. Patrick married Mary about 1892, and they had seven children, five of whom survived, Annie (born in July 1893), William (December 1896), Patrick (May 1899), Peter (1904) and Thomas, the youngest. The father died while Tom was a child, so he lived with his brother-in-law, his sister, and their three children. In 1920, Patrick, Peter, and Thomas were living with their widowed mother at 807 Willow Avenue in Hoboken. In 1930, Patrick (by then a policeman), Peter, and Thomas were living with their mother at 1118 Park Avenue. After attending Hoboken’s Our Lady of Grace grammar school, where he played basketball as well as baseball, Carey went to work in one of the city’s industrial shops, but he continued to play ball.

Known as “Scoops” or “The Hoboken Harp,” the 5-foot-8, 170-pound right-hander began his professional baseball career in 1928, sticking briefly with Jersey City in the International League before he was released. The next year, Carey caught on with the West New York and New Jersey semipro club, a strong team that played the Bushwicks, the Cuban Giants, and Philadelphia Giants.

Carey was playing semipro ball in New York in 1930 when Yankees scout Paul Krichell signed him to play shortstop for the pennant-winning Chambersburg (Pennsylvania) Young Yanks of the Class D Blue Ridge League. Carey hit .306 with 10 home runs in 107 games. Near the end of that season, he was transferred to Scranton of the Class B New York-Pennsylvania League, where St. Louis Cardinals scout Charley Kelchner acquired him to play with Houston in the Texas League the following year. At Houston, Carey starred at shortstop behind Dizzy Dean (Paul Dean, Billy Myers, Tex Carleton, and Joe Medwick were also on that team), batting.240 with 15 doubles and 8 triples. In 1932, he played in 142 games for Houston and 20 for Columbus in the American Association. His average with Houston jumped to .270 but in his 68 at-bats for Columbus, he hit only .191.

In 1933, Scoops was transferred to Rochester of the International League, where he had three strong seasons. After he hit.297 and .287 in his first two seasons, the Cardinals took him to spring training in Bradenton, Florida, in 1935, but sent him back to Rochester, where he became the team captain. In July 1935, Carey, batting .301, was purchased from Rochester by the St. Louis Browns to replace the disabled Ollie Bejma at second base. (2) A Browns publicist described Carey as “the outstanding prospect among minor league infielders.” Although he was a light hitter, Carey “never failed to sparkle on defense,” and he was regarded as “an aggressive, fighting player who will go after any ball and run out the weakest of pop flies.”

Carey’s major-league debut on July 19 with Rogers Hornsby’s Browns came as a surprise. When the 28-year-old infielder reported to the Browns manager at Yankee Stadium, Hornsby growled, “You were supposed to be here yesterday,” and told the rookie that he would play second base. In the minor leagues, Carey had played only shortstop, but he became adept at the new position after committing a league-high 25 errors in 1936. (3)

He broke in nicely, going 2-for-4 with two doubles and a run batted in as the Browns beat the Bronx Bombers, 7-6. Carey’s most productive day that year was probably the August 11 doubleheader, when he was 1-for-4 and 4-for-5. Although the Browns finished seventh in 1935, Carey hit .291 in his rookie season, with 22 extra-base hits (no homers) and drove in 42 runs, while playing second base in 76 games.

He had two productive seasons in St. Louis: In 1936, he played a career-high 134 games, hitting .273 with 27 doubles, 6 triples, 58 runs scored, and 57 runs batted in; the next year, he hit .275 with 24 doubles, 54 runs, and 40 RBIs in 130 games. He hit two home runs in his career, both solo shots, on August 2, 1936, and June 16, 1937. Even though Hornsby had played only occasionally since the 1931 season, his biographer nonetheless noted Carey’s arrival on the scene in the spring of 1937: “Hornsby …sat down in favor of Tom Carey, and from then on, regardless of front-office wishes, he was willing to play only when it wasn’t cold and the ground was dry.” (4)

The Browns had a new manager in 1938, Gabby Street, and after two seasons as a full-time player, Carey was optioned to the Pacific Coast League’s Hollywood Stars, where he played shortstop and batted .297 in 157 games. During the 1938 season, the Browns acquired Don Heffner from the Yankees to replace Carey at second base, and on December 6, 1938, St. Louis traded Carey to the Boston Red Sox for pitcher Johnny Marcum. In Boston, Scoops served as a utility infielder; manager Joe Cronin called Carey “an excellent infield insurance policy.” During spring training, Edwin Rumill of Boston’s Christian Science Monitor commented, “Tom Carey played a sparkling defensive game at second base. …Too bad he doesn’t hit.” (5)

Backing up second baseman Bobby Doerr and shortstop-manager Cronin in 1939, Carey appeared in only 54 games—the most he ever played in a single season with the Red Sox.

Carey accumulated 161 at-bats (he averaged .242) and drove in 20 runs. In 1940, he had only 62 at-bats, mostly filling in when Bobby Doerr pulled a muscle in early June and when Cronin benched himself with a severe head cold in mid-July. Carey drove in seven runs (one of them a single in the 13th inning to win the September 10 game), and batted .323, but there just wasn’t the room for him to play more regularly. With the addition of utility man Skeeter Newsome to the Red Sox in 1941, he hit .190 in 21 at-bats without an extra-base hit and without driving in a run – though he scored seven.

Carey saw his already limited playing time dwindle to two innings in 1942, leading one newspaper wag – exactly who is uncertain because the newspaper article is incomplete — to label him “baseball’s Forgotten Man” and note that Fenway Park patrons saw him play only during infield practice: “A member of the Red Sox in good standing, he has spent 99 44-100 per cent of his time on the bench.” During his brief appearance on the field that year, the Forgotten Man had one hit in a single at-bat, drove in a run, and fielded one chance cleanly—a perfect 1.000 performance. Nevertheless, the Associated Press (which called him “Boston’s $5,000-a-hit player”) argued that Carey’s “backstage activities” — warming up pitchers and throwing batting practice to the regulars, earned his $5,000 salary.

With Johnny Pesky in the Navy after the 1942 season, it looked as though Carey would get a shot at shortstop, but on the very day — Valentine’s Day — that he received his contract for 1943, he also received notice of reclassification as 1A in the draft and was ordered to report for his physical.

Carey served in the Navy from 1943 to 1945, primarily as baseball coach at the Sampson Naval Training Base in upstate New York. He returned to the Red Sox briefly as a player for their pennant-winning 1946 season. Rosters were swollen in the first year after the war to permit clubs to accommodate returning servicemen, but many saw little playing time. It would not be surprising if Carey, then 37 and having lost three years of major-league-caliber baseball, were a little rusty. But Tom declared himself in better shape than ever, having lost weight and kept fit. “I don’t see any reason why I couldn’t go for five more years,” he said. “I mean that.” The Monitor’s Ed Rumill observed that Carey “has been out-playing, out-hustling, and even out-hitting most of the younger infielders in camp.”

Carey had experience at second, third, and short and offered a steady backup. From spring training, Rumill praised him in print: “A more popular team ballplayer has never had a locker at Fenway. And he is a good hustler. A man who fits in with your team spirit and can step in and play three of the four infield positions is a handy weapon when you are on the prowl for the pennant. History insists that a contender is no stronger than its reserves, and Carey has, in the past, been an ideal reserve.” Rumill foresaw another possible role: “If Cronin feels that he no longer has room for Carey on the varsity … he has the experience and intelligence to fill a coaching or even a managerial berth.”

After the opening bell, Carey got little playing time. He had just one single in five at-bats, usually as a late-inning substitute during games that had become lost causes. In midseason, Rumill wrote, “Cronin had so many infielders, even before the arrival of [Don] Gutteridge, that some of them had to dress in the room adjacent to the regular Sox clubhouse.” (6) Carey was indeed made a coach on the team. “I’d like to stay in baseball, naturally,” he said. “But that’s up to the Red Sox. I’m ready to take any job they give me.” (7)

On October 30, 1946, Boston released the 40-year-old Carey, along with Mace Brown, Mike Ryba, and Charlie Wagner, hiring all four in other capacities. Carey was sent to Wellsville, New York, where he managed the Red Sox’ farm team in the Class D PONY League in 1947 and 1948. In 1949 and 1950, he coached for the Red Sox Birmingham, Alabama, affiliate in the Southern Association.

We know almost nothing about Carey’s life after baseball. He died from liver disease on February 21, 1970, at Highland Hospital in Rochester, New York. He is buried in Rochester’s Holy Sepulchre Cemetery. He was survived by his wife, Grace M. Carey, who died in 1998.

Notes

1. Tucker, Walter Dunn. “How Old Is That Guy, Anyway?” Baseball Research Journal 36 (2007): 94-98.

2. Alexander, Charles. Rogers Hornsby. New York: Henry Holt, 1995: 199.

3. Shatzkin, Mike, ed. The Ballplayers. New York: Arbor House, 1990: 158.

4. Alexander, op. cit.: 211.

5. Christian Science Monitor, March 30, 1946. Carey’s playing weight may have increased by the time he got to Boston. Rumill dubbed him a “chubby veteran” when he signed his 1942 contract and later a “pleasant-faced New Yorker, on the roly-poly side.”

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

Sources

Alexander, Charles. Rogers Hornsby. (New York: Henry Holt, 1995)

Ancestry.com.

Baseball-reference.com.

Carey, Thomas. Clipping File. National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Shatzkin, Mike, ed. The Ballplayers. (New York: Arbor House, 1990)

The Sporting News.

Tucker, Walter Dunn. “How Old Is That Guy, Anyway?” Baseball Research Journal 36 (2007): 94-98. This article asserts that Carey claimed a 1909 birthdate, but since all other sources – including contemporary ones — cite 1908, we have elected to keep that date.

Full Name

Thomas Francis Aloysius Carey

Born

October 11, 1906 at Hoboken, NJ (USA)

Died

February 21, 1970 at Rochester, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.