May 9, 1919: Pete Alexander’s return from World War I spoiled by Ray Fisher, Reds

There died a myriad of them,

And of the best, among them,

For an old bitch gone in the teeth,

For a botched civilization, …

— Ezra Pound, Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920)

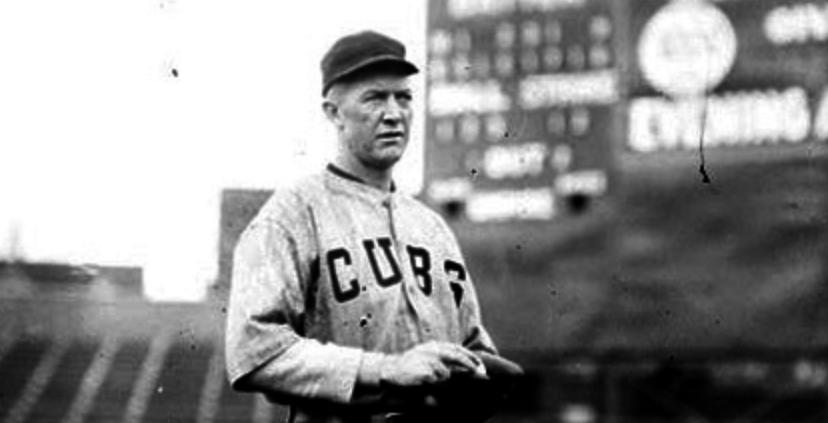

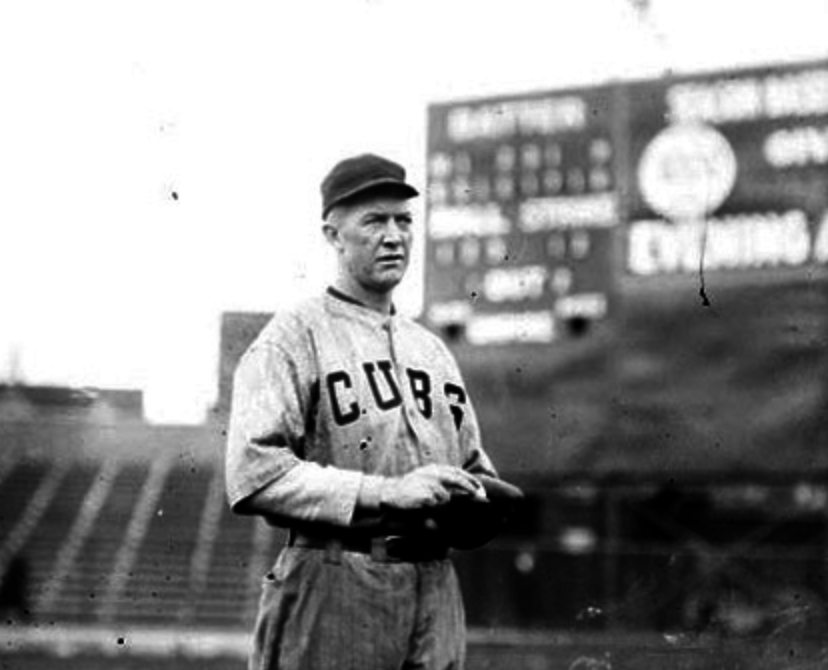

Friday, May 9, 1919. The Armistice ending the Great War was nearing its six-month anniversary. The Spanish influenza pandemic hadn’t loosened its death grip. The Reds and Cubs had returned to Chicago from their series in Cincinnati. And Grover Cleveland Alexander, back from his stint in France with the 89th Division and 342nd Field Artillery, was ready to take the mound for the first time since April 26, 1918.

Friday, May 9, 1919. The Armistice ending the Great War was nearing its six-month anniversary. The Spanish influenza pandemic hadn’t loosened its death grip. The Reds and Cubs had returned to Chicago from their series in Cincinnati. And Grover Cleveland Alexander, back from his stint in France with the 89th Division and 342nd Field Artillery, was ready to take the mound for the first time since April 26, 1918.

Alexander was one of another “myriad” of men — those who survived the war but never recovered from it. He had spent seven weeks at the front. “[R]elentless bombardment left him deaf in his left ear. Pulling the lanyard to fire the howitzers caused muscle damage in his right arm. He caught some shrapnel in his outer right ear, an injury thought not serious at the time but which may have been the progenitor of cancer [necessitating its amputation] almost thirty years later. He was shell-shocked.”1 Even worse, he was facing the onset of alcoholism and epilepsy.

Facing Alexander was Ray Fisher, described by The Sporting News in its May 15 issue in an encapsulation of the game as “an American League discard.”2 Having been drafted into the Army in 1918, he had spent the war at Fort Slocum near New Rochelle, New York.3

As games go, the Reds’ 1-0 victory in front of 5,000 spectators at Weeghman Field (now known and loved as Wrigley Field) showed little out of the ordinary — just a wild double play in the Cubs’ fifth that was scored catcher to pitcher to second to catcher. Slightly unusual perhaps was that three of the Cubs’ four hits were doubles (two by Charlie Hollocher, the other by Charlie Deal). That the doubles led off the fourth, fifth, and sixth innings and produced no runs may be fodder for Retrosheet. Otherwise, the game consisted of two pitchers exchanging zeroes until one of them broke.

Indeed, the only number that might jump off the box score is Alexander’s surrendering of five walks. According to Retrosheet, he walked eight batters in a game once, six in a game five times (all early in his career, from 1911 to 1913), and five in a game 20 other times.4

Alexander was in trouble for much of the game; five hits and five walks over eight innings will do that. (Had the Pirates’ longtime announcer Bob Prince been on the scene, he would have said, “Alexander’s been running through the raindrops all day.”) Only in the first and fifth innings did he retire the Reds in order. Trouble began in the second when Wally Rehg and Sherry Magee singled. Alexander retired Jake Daubert and Larry Kopf but walked Bill Rariden to load the bases. Fisher struck out, leaving three on. In the fourth, Alexander walked Daubert and Rariden but escaped by forcing Fisher to ground out. He survived walking Magee in the sixth. One of the many clichés of baseball is that “Walks come back to haunt you,” and that’s what happened in the eighth. Alexander walked Heinie Groh. Rehg sacrificed Groh to second, and Magee doubled him home for the game’s only run.

On the other hand, Fisher’s performance (four hits, two walks, no strikeouts) was reasonably typical for him.5 He shut things down when he had to, surviving threats in the fourth (a leadoff double by Hollocher followed by a walk to left fielder Turner Barber before retiring the next three batters); fifth (a leadoff double by Charlie Deal, a fly out by Bill Killefer, a single by Alexander, and right fielder Max Flack flying into the odd double play); and sixth (another leadoff double by Hollocher, Barber’s sacrifice getting him to third, the opportunity ended by center fielder Dode Paskert hitting into a double play going pitcher to first to home). Fisher breezed through the final three innings, walking Paskert with two out in the ninth.

Sometimes an apparently ordinary, routine game becomes more significant in light of its aftermath, and the game featuring Alexander’s return is one of them. At the end of play on May 9, not quite 10 percent of the way through the 140-game season, the Reds were 10-3, a half-game behind the Brooklyn Robins (9-1-1). The Cubs, defending National League champs, stood at 7-5 in fourth place. The Robins faded to 69-71, good only for fifth place at the end of the season. The Reds finished atop the NL at 96-44 and went on to defeat the Chicago White Sox in the most controversial World Series ever. The Cubs’ 75-65 slate brought them in third, well out of contention.

For Alexander, the 1919 season was an up-and-down affair. Pitching seven times in May (five starts), he lost all four of his decisions and finished the month with an ERA of 4.24. Starting five games through June 17 (two shutouts and four complete games) and winning four, he appeared to be back in his groove. But he didn’t pitch again until July 15, apparently because of arm trouble. According to the late SABR historian Jack Kavanagh, “Cubs trainer Fred Hart massaged Pete’s arm and back daily. He soaked in hot tubs and stood under icy showers. The diagnosis was that he was muscle bound, having pitched too soon.”6 Intriguing diagnosis aside, he went 5-3 in August, put together a modest four-game winning streak, and dropped his ERA to a season-low 1.69. Alexander lost three in a row to start September but finished the month strong with four straight wins, the last two being shutouts. It all added up to a 16-11 mark, far off his accustomed prewar 30-win seasons but softened by getting his control back (121 strikeouts against 38 walks in 235 innings pitched), a league-leading nine shutouts, and a league-leading 1.72 ERA, the lowest ERA by a Cubs pitcher since the team started play in Wrigley Field in 1916.

Though early in the season, Fisher boasted a 4-0 record with a barely visible ERA of 1.00. He struggled a bit through the rest of May and all of June, then didn’t pitch from June 29 until July 14, mopping up in an 8-1 loss in Philadelphia. He pitched again on July 31, shutting out the Boston Braves, 5-0, starting a seven-game winning streak that led to a 14-5 finish with a 2.17 ERA. He pitched well in Game Three of the World Series but lost to Dickey Kerr, 3-0.

For Alexander and Fisher, the future couldn’t have been more different. No longer a great pitcher but still a very good one, Alexander pitched through the 1920s with three 20-win seasons (with 1920 proving reminiscent of his old brilliance) and the legendary bases-loaded strikeout of Tony Lazzeri in Game Seven of the 1926 World Series. Fisher pitched in 1920. In 1921, in a series of machinations and miscommunications involving Reds manager Pat Moran, Reds owner August Herrmann, National League President John Heydler, and Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, Fisher landed on the Ineligible List and then baseball’s Permanent Ineligible List.7

Life after baseball for Alexander — except for induction into the Hall of Fame in 1939 — was a hell comprised of alcoholism, epilepsy, divorce, and demeaning work until his death on November 4, 1950. Life couldn’t have worked out better for Fisher. He became head baseball coach at the University of Michigan, serving from 1921 to 1958; under his tutelage the Wolverines went 661-292, took 14 Big Ten titles, and won the national championship in 1953. During the summers he returned to his native Vermont and occasionally pitched and managed semipro ball. He lived to be 95, dying on November 3, 1982.

A trio of footnotes, as it were, emerged from the game. It was Wally Rehg’s next-to-last game; the next day he drove in the last two runs of his career in a 4-3 loss to the Cubs’ Jim Vaughn. Sherry Magee’s near-Hall-of-Fame career was winding down just a year after he’d led the NL in RBIs. His game-winning hit was his fourth double of the young season and two-thirds of his total for 1919. Missing was Cincinnati star center fielder Edd Roush, who had injured his shoulder on May 5 trying to make a diving catch in a 7-6 loss to the Cubs; he returned to action on May 14.

Friday, May 9, 1919, was undoubtedly a big day in the lives of some people in Weeghman Field. The game changed little, not even the NL standings because all the other scheduled games were rained out. The Armistice was still holding. The Spanish flu was still claiming victims. But Grover Cleveland Alexander was back.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Bill Nowlin, Alan Cohen, Michael Huber, Carl Riechers, and Len Levin for their encouragement, editing, fact-checking, and suggestions. They made this story better.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, BioProject biographies of some of the participants, and a manuscript of a forthcoming book by Jim Leeke with the working title Shadows and Ghosts: Grover Cleveland Alexander and Baseball’s Artillerymen during the Great War, to be published by University of Nebraska Press in late 2020 proved useful.

Notes

1 Jan Finkel, “Pete Alexander,” SABR BioProject. sabr.org/bioproj/person/79e6a2a7.

2 “National League. Game of Friday, May 9,” The Sporting News, May 15, 1919: 6.

3 Chip Hart, “Ray Fisher,” SABR BioProject. sabr.org/bioproj/person/2ab8da34.

4 Alexander’s reputation for pinpoint control is borne out by his 951 walks in 5,190 innings pitched, making this game an aberration and possible evidence of some rustiness.

5 In 174⅓ innings pitched in 1919, he struck out 41 batters and issued 38 walks.

6 Jack Kavanagh, Ol’ Pete: The Grover Cleveland Alexander Story (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, Inc., 1996), 73.

7 Chip Hart provides the details in “Ray Fisher.” The central issues appear to be (a) whether Fisher had or had not received permission from the Reds to interview for a coaching position at the University of Michigan, and (b) whether Fisher remained under contract to the Reds or had been released when he interviewed and entered negotiations for the position.

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Reds 1

Chicago Cubs 0

Weeghman Field

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.