October 1, 2006: Devern Hansack throws an ‘unofficial’ no-hitter for Red Sox

When does a pitcher throw a complete-game shutout without giving up even one base hit, leaving the game with a win, but somehow that’s not a no-hitter? It sort of defies logic. You pitched. You were the only pitcher for your team. You won the game. It’s in the record books as a complete-game win. And you never gave up a hit.

When does a pitcher throw a complete-game shutout without giving up even one base hit, leaving the game with a win, but somehow that’s not a no-hitter? It sort of defies logic. You pitched. You were the only pitcher for your team. You won the game. It’s in the record books as a complete-game win. And you never gave up a hit.

The answer is fairly well known, however unsatisfying it may be. According to an edict from Major League Baseball, if you pitch fewer than nine innings, a game such as that is not a no-hitter. Even though there were no hits. And it is counted as a complete game.

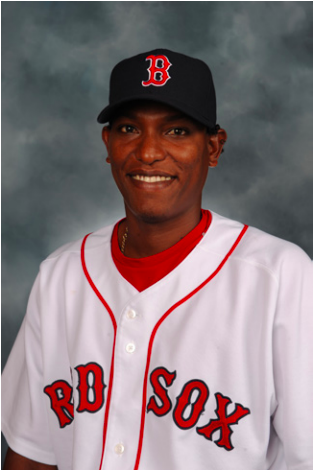

Pitching in only his second game in the majors, Nicaraguan righty Devern Hansack of the Boston Red Sox faced the Baltimore Orioles at Fenway Park. It was Sunday, October 1 — the very last game of the 2006 regular season.

The Orioles were solidly in fourth place with a record of 70-91. The Red Sox were in third place but just one game behind the Toronto Blue Jays (Boston was 85-76 and Toronto was 86-75). If Toronto lost its game against the New York Yankees and Boston won its game, the two teams would be tied at 86-76. Neither had a shot at a wild-card berth, however.

Hansack hadn’t even been in Organized Baseball at the beginning of 2005. He was on the Nicaraguan team, playing at an international tournament in The Netherlands, when a tip to Red Sox international scouting chief Craig Shipley resulted in a $3,000 offer for Hansack to sign a contract with the Red Sox. He enjoyed a very good year at Double-A Portland, helping the team to the postseason and being named the team’s MVP. He had been brought up to the majors in the waning days of the year. At Fenway Park, he was working out of a temporary locker in the Red Sox clubhouse. Hansack lost his first start, 5-3, in Toronto on September 23. Now, with little on the line, he was asked to pitch the last game and close out the season. Pitching for the O’s was right-hander Hayden Penn.

The game was delayed for quite a long time by bad weather, a mere 3-hour and 23-minute rain delay. Both teams wanted to get the game in. It didn’t get underway until 5:28 P.M. The game time temperature was 56 degrees, with a 12 mph wind coming in from center field. There was a continuous drizzle, and the field condition was wet. But home-plate umpire Rob Drake set himself behind Boston catcher Jason Varitek and gave Hansack the signal to start the game.

The attendance was purportedly 35,826. In reality, most of those who had purchased tickets never showed up. A groundout, a strikeout, and a fly ball to center, and the O’s were set down in order on 11 pitches.

Even though David Ortiz popped up foul to the catcher, the two batters before him had gotten on base and Mike Lowell hit a three-run homer. Red Sox, 3-0.

With one out in the top of the second, Hansack walked Fernando Tatis, but two pitches later retired the side on a double play. Tatis was the only Orioles batter to reach base in the game. Hansack retired the side in order in the third.

In the bottom of the third, Penn imploded. He got two men out, but two walks sandwiched around a single loaded the bases. Then he walked Carlos Pena, forcing in the fourth Red Sox run. And on the first pitch he saw, center fielder Gabe Kapler hit a bases-clearing double to left. It was now 7-0 in favor of the Red Sox, and Baltimore manager Sam Perlozzo called in Julio Manon to take over for Penn. Manon did his job and secured the third out.

In the fourth Hansack had another 1-2-3 inning. Manon gave up a solo home run, hit over the Green Monster, to Mark Loretta. With an 8-0 lead, and the weather still very unpleasant, the Red Sox replaced Ortiz, Loretta, and Trot Nixon. For Nixon, it was his last game for the Red Sox, and manager Terry Francona had sent him out to right field, only to call him back in so that the fans could give him a final round of applause.

Two strikeouts and a fly ball to center field, and Hansack retired the Orioles in the top of the fifth. Given that the Red Sox held the lead, it was now an official game. Hansack had walked the one batter, and struck out six, but not given up a hit. In fact, none of the balls the Orioles hit was even close to a base hit.

But the umpires hadn’t given up on the game, so the Red Sox batted again in the bottom of the fifth as Hansack tried to keep as warm and dry as he could sitting on the bench in the Boston dugout. Eric Hinske hit a solo home run for Boston, off new Baltimore pitcher Russ Ortiz, and the score stood 9-0. Pena reached first on a base on balls, but this time Kapler hit into a double play and Alex Cora grounded out to end the Red Sox fifth.

At this point, play was halted due to a worsening of the weather, and the tarp pulled over the infield in the vain hope that the game could be resumed.

Had he been aware that he was pitching a no-hitter, as it was in progress? “Well, in the beginning, I didn’t take notice until I came out after the fourth inning.”1

It proved impossible to continue and after another 41-minute rain delay, the game was called. Those present had seen a no-hitter. But not according to major-league baseball. Back in 1991, the powers that were — the committee for statistical accuracy — had decided to issue a definition of a “no-hitter.” It wasn’t a game in which one team failed to get a hit. According to the committee’s edict, “A no-hitter is a game in which a pitcher or pitchers complete a game of nine innings or more without allowing a hit.”2

Perhaps the game that prompted someone feeling the need to define “no-hitter” was the six-inning, rain-shortened no-hitter at Yankee Stadium on July 12, 1990, when Melido Perez no-hit the Yankees, 8-0. It was a no-hitter the day he threw the game. A year later it was not. Perez was deprived of his no-hitter because of a committee ruling.

It wasn’t just Perez who lost his no-hitter. So, too, did 35 other pitchers, some of whom had gone to their graves believing they’d pitched a no-hitter (something everyone else had believed, too). A half-dozen or so of the pitchers who in effect had to turn in their honors were still among the living. For years, some of them had “no-hitter” on their résumé, maybe a ball signed by the umpire or by their catcher or teammates — only to wake up one day and been told they had no longer earned that distinction.3

Not only did all those pitchers lose their distinction, but so did their catchers.

Jason Varitek of the Boston Red Sox didn’t lose the honor, because he never had it. The definition of a no-hitter had been changed (in 1991), years before Varitek caught Hansack’s game. But the consequence of the edict deprived him of what would have been a unique accomplishment — the only catcher in major-league history to have caught five no-hitters.

Varitek had previously caught “official” no-hitters by Hideo Nomo (in 2001) and Derek Lowe (2002), and later caught ones by Clay Buchholz (2007) and Jon Lester (2008). Working in sync with your pitcher and calling a no-hitter is in very large part an accomplishment by the catcher as well, and Varitek holds the record with four. As Buchholz told Dirk Lammers, “Pitchers put a lot of trust in their catchers, whether it’d be knowing you can bounce a curveball with a runner on third and know if they’re going to block it and pitch calling. That was really early in my career, so I didn’t really have any idea who I was throwing to, what they hit well, what they didn’t hit well.”4

Carlos Ruiz has subsequently caught four “official” no-hitters as well — two by Roy Halladay in 2010 (the first one a perfect game), one in 2014 (a combined effort involving four pitchers), and one in 2015. So Ruiz has now tied Varitek, but had Hansack’s no-hitter not been ruled a “notable achievement,” Varitek would have five.

Hansack’s complete-game shutout was the first one a Red Sox pitcher had thrown since Pedro Martinez had done it on August 12, 2004.

“I wasn’t disappointed because nobody can stop the rain,” Hansack said after the game. “That was fun, wasn’t it, seeing him change speeds with the rain dripping off his cap,” manager Francona said. “The way he was able to throw strikes, he was really something special.”5

This article was published in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin. To read more Games Project stories from this book, click here.

Sources

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BOS/BOS200610010.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/2006/B10010BOS2006.htm

Notes

1 Author interview with Devern Hansack, September 23, 2016.

2 The committee was prompted by Commissioner Fay Vincent. Another determination made by the committee was to reaffirm prior practice (since 1968) that no asterisk needed to be placed next to the names of players like Roger Maris, who had hit 61 homers in a 162-game season, surpassing Babe Ruth‘s 60 struck when the seasons were 154 games long. The decision was that “Rain-shortened games or others … of fewer than nine innings will be considered ‘notable achievements,’ not no-hitters, and will be listed separately.” Murray Chass, “Maris’s Feat Finally Recognized 30 Years After Hitting 61 Homers,” New York Times, September 5, 1991.

3 Dirk Lammers, in his enjoyable and comprehensive book Baseball’s No-Hit Wonders lists the 36 pitchers and provides dates and details of their games. In sequential and not alphabetical order, they were nineteenth-century pitchers Larry McKeon, Charlie Geggus, Charlie “Pretzels” Getzien, Charlie Sweeney, Henry Boyle, Fred “Dupee” Shaw, George Van Haltren, Ed Crane, Matt Kilroy, George Nicol, Hank Gastright, Jack Stivetts, Elton “Ice Box” Chamberlain, and Ed Stein. (Sweeny and Boyle had pitched a combined no-hitter.) Those twentieth-century pitchers who had their honors scrubbed from the books were Red Ames, Rube Waddell, Jake Weimer, Jimmy Dygert (who joined Waddell in a combined no-hitter — making Rube a two-time “loser”), Stoney McGlynn, Lefty Leifield, Ed Walsh, Ed Karger, Howie Camnitz, Harry “Rube” Vickers, Johnny Lush, Len “King” Cole, Carl Cashion, Walter Johnson, Fred Frankhouse, John Whitehead, Jim Tobin, Mike McCormick, “Toothpick” Sam Jones, Dean Chance, David Palmer, Pascual Perez, and Melido Perez. See Dirk Lammers, Baseball’s No-Hit Wonders (Lakewood, Colorado: Unbridled Books, 2016), 381-387.

4 Dirk Lammers interview with Clay Buchholz, May 20, 2015. Ibid., 261.

5 Howard Ulman, Associated Press, October 1, 2006. A blogger noted that with the win, Hansack became the “sixth-winningest Nicaraguan pitcher in MLB history” (see smoaky.com/forum/index.php?showtopic=59716):

1. Dennis Martinez, 245.

2. Vicente Padilla, 66.

3. Albert (DeSouza) Williams, 35.

4. Porfi Altamirano, 7.

5. Oswaldo Mairena, 2.

6. Devern Hansack, 1.

Additional Stats

Boston Red Sox 9

Baltimore Orioles 0

5 innings

Fenway Park

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.