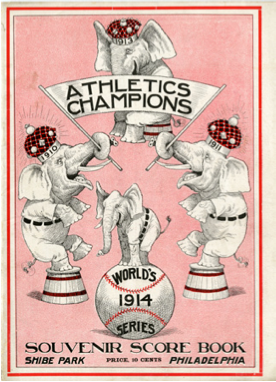

October 12, 1929: A’s stage historic World Series comeback with 10-run inning

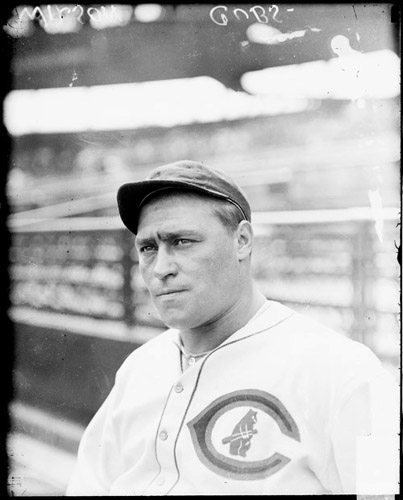

The Chicago Cubs’ Hack Wilson jogged out to his position in center field to start the home half of the seventh inning. Turning toward the diamond, he again took note of the late afternoon sun, which had descended to a point almost directly above Shibe Park’s double-decked grandstand behind home plate. The dazzling orb’s slanting rays were now aimed straight into his eyes. It had already made trouble for Wilson. Two innings earlier, in this fourth game of the 1929 World Series against the Philadelphia Athletics, he had dropped a fly ball after losing it in the October brightness. But he made a spectacular running, leaping grab of a deep fly off the bat of Joe Boley, the next batter. To many observers, it was one of the finest catches they’d ever seen in a World Series. Then, in the sixth, he had trouble with another ball because of the sun, but was able to corral it.

The Chicago Cubs’ Hack Wilson jogged out to his position in center field to start the home half of the seventh inning. Turning toward the diamond, he again took note of the late afternoon sun, which had descended to a point almost directly above Shibe Park’s double-decked grandstand behind home plate. The dazzling orb’s slanting rays were now aimed straight into his eyes. It had already made trouble for Wilson. Two innings earlier, in this fourth game of the 1929 World Series against the Philadelphia Athletics, he had dropped a fly ball after losing it in the October brightness. But he made a spectacular running, leaping grab of a deep fly off the bat of Joe Boley, the next batter. To many observers, it was one of the finest catches they’d ever seen in a World Series. Then, in the sixth, he had trouble with another ball because of the sun, but was able to corral it.

Luckily for the Cubs, Wilson’s struggles had not resulted in any damage. Their starting pitcher, Charlie Root, winner of 19 games in 1929, was cruising, having allowed only three hits. Chicago’s vaunted offense, meanwhile, had taken an 8-0 lead. It simply was not the Athletics’ day.

Nine more outs was all Root needed. Nine more outs, and the Series would be tied at two games apiece. Just two days ago, the Series had seemed all but over, the Athletics having won the first two contests at Wrigley Field, including a 13-strikeout gem by seldom-used journeyman Howard Ehmke. Chicago took Game Three, however, in a hostile Shibe Park, behind Guy Bush’s tough pitching. Now, the momentum seemingly had shifted back to manager Joe McCarthy’s Cubs. They had 22-game-winner Pat Malone ready for Game Five, and the final two would be back at Wrigley, where Chicago had been nearly unbeatable that summer, at 52-25. Only the Athletics, at 57-16, had had a better home record in the majors in 1929.

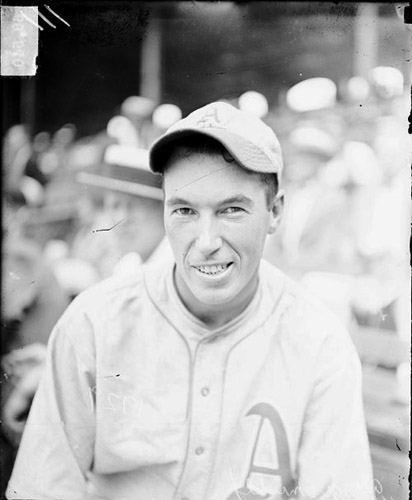

Al Simmons, Philadelphia’s slugging left fielder, led off the seventh. On Root’s third offering, “Bucketfoot Al” hit a home run to left that cleared the roof. The shutout was lost, and the home crowd finally had something to cheer about. Root took a new ball from home plate umpire Roy Van Graflan.

Jimmie Foxx singled, and Bing Miller hit a fly ball to center. The staggering Wilson lost it in the sun, and it fell in for a single, with Foxx taking second. Singles by Jimmy Dykes and Boley scored Foxx and Miller to make it 8-3.

With runners on first and third and nobody out, George Burns pinch hit for pitcher Eddie Rommel. He was quickly dispatched on a pop fly to shortstop Woody English, the runners holding.

Max Bishop, who had hit only .232 during the regular season but had also led the league with 128 walks, singled to left, scoring Dykes, sending Boley to third. Suddenly, the Cubs lead had been cut in half. McCarthy headed to the mound, took the ball from a frustrated Root, and waved in lefty Art Nehf from the bullpen to face the left-handed-hitting Mule Haas.

In center field, Wilson adjusted his cap and dark sunglasses, the better to peer in against the blinding beams of the sun. At 29, Wilson had led the National League in home runs three of the previous four seasons. Born in the steel mill town of Ellwood City, Pennsylvania, he was the illegitimate son of an alcoholic steelworker and a teenage mother who died when he was seven.

Wilson didn’t appear athletic at 5 feet 6 inches tall, 190 pounds, with an 18-inch neck, spindly lower legs, and size 5 1/2 feet that only a ballerina could love. Yet he could hit a baseball a mile. He began his big-league career with the New York Giants. But manager John McGraw, the dinosaur disciple of small ball, wasn’t won over by the top-heavy Wilson, despite his .295 average in a limited role in his rookie year of 1924. The Giants traded him to the Toledo Mud Hens in August of 1925. Following that season, the Cubs, in an unnoticed transaction, acquired Wilson in the Rule 5 draft.

Wilson and Jazz-Age Chicago were partners in perfect pitch. In awe of his clouts onto Waveland Avenue, Wrigley Field’s denizens cheered him in the afternoon, and then toasted him late into the night as he made the rounds of the Windy City’s numerous speakeasies. In 1930, his annus mirabilis, Wilson whacked 56 home runs, and established a major-league single-season record with 191 RBIs, one of baseball’s most enduring numbers. 1931 was Wilson’s annus horribilis, with only 13 home runs and 61 RBIs; within three years his career was finished, the fall precipitated by alcohol and riotous living. He gained induction into Cooperstown in 1979, 31 years after his death. But on the late afternoon of October 2, 1929, at the corner of 21st and Lehigh in the City of Brotherly Love, Hack Wilson was about to engage in combat one too many times with Hyperion the sun-god, and end up getting burned.

One out, runners on first and third, 8-4 in favor of Chicago. Mule Haas, who had hit 16 home runs in 1929, sent Nehf’s first fastball on a line toward center field. Wilson drifted back. Despite his sunglasses, he again lost the ball in the glare. It soared over his head and rolled to the fence. The desperate outfielder ran the ball down, Boley and Bishop scoring. Haas, defying his nickname, sprinted like lightning around the bases. Wilson heaved a late throw in, and Haas slid into the home dish in a cloud of dust. Safe, declared Van Graflan.

One out, runners on first and third, 8-4 in favor of Chicago. Mule Haas, who had hit 16 home runs in 1929, sent Nehf’s first fastball on a line toward center field. Wilson drifted back. Despite his sunglasses, he again lost the ball in the glare. It soared over his head and rolled to the fence. The desperate outfielder ran the ball down, Boley and Bishop scoring. Haas, defying his nickname, sprinted like lightning around the bases. Wilson heaved a late throw in, and Haas slid into the home dish in a cloud of dust. Safe, declared Van Graflan.

The Cubs had blinked, and the score was suddenly Chicago 8, Philadelphia 7, with only one out.

The 36-year-old Nehf, winner of 184 games over 15 seasons, walked Mickey Cochrane. McCarthy, for the second time in the inning, marched out to the mound, and Nehf, for the final time in his big-league career, marched off of it.

Enter pitcher John Frederick “Sheriff” Blake, who failed to lay down the law. Al Simmons, back in the saddle for the second time that inning, singled to left. Foxx did the same, scoring Cochrane to tie it. McCarthy yanked the badge off Blake and tried his luck with Pat Malone, who plunked Bing Miller with his first pitch. Jimmy Dykes doubled, driving in two more to put the Athletics up by a deuce.

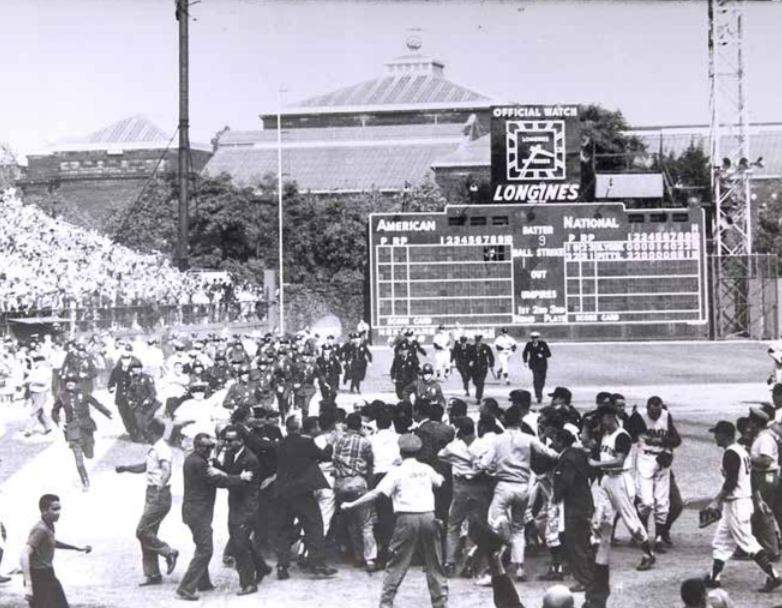

The Shibe Park crowd was delirious with delight. Strikeouts by Boley and Burns brought the frame to an end, but the book had already been written.

Athletics manager Connie Mack brought in Lefty Grove, winner of 20 in 1929, to start the eighth. He fanned four of the six batters he faced. At 3:42 pm, Rogers Hornsby flied to left for the final out of the game. Wilson was left on one knee in the on-deck circle.

What had looked like a 2-2 Series tie had suddenly become a three-games-to-one Athletics lead. Chicago never recovered. They lost the Series the following day in equally heartbreaking fashion, when Philadelphia scored three runs in the bottom of the ninth to wipe out a 2-0 Cubs lead.

Declared Mack to his men after Game Four, “I’d just like to be able to express to you the things I feel. But I can’t. I’ll have to let it go at that.” To reporters he gushed, “I’ve never seen anything like that rally. There is nothing in baseball history to compare it with. It was the greatest display of punch and fighting ability I’ve ever seen on a field.”1

In the dejected Cubs clubhouse, McCarthy mumbled, “You can’t beat the sun, can you?”2 Then, in an effort to deflect blame from his star center fielder, he pointed out, “The poor kid simply lost the ball in the sun, and he didn’t put the sun there.”3

Ed Burns of the Chicago Tribune wrote, “The greatest debacle, the most terrific flop in the history of the World Series. We’ve been looking at our score book for an hour now, thinking there must have been some horrible mistake, but ten she is folks.”4

“Couldn’t see the balls,” Wilson clarified.5 “I’m a big chump, and nobody’s going to tell me different.”6

Wilson and his four-year-old son Bobby departed the park together in a taxi. “The devil with them, Daddy,” he remarked. “We’ll get them next year.”7

Sources

Chastain, Bill. Hack’s 191: Hack Wilson and His Incredible 1930 Season (Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press), 2012.

Kashatus, Bill. Connie Mack’s ’29 Triumph (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland), 1999.

Notes

1 Roberts Ehrgott, Mr. Wrigley’s Ball Club: Chicago and the Cubs During the Jazz Age (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013), 200.

2 Ibid., 201.

3 Clifton Blue Parker, Fouled Away: The Baseball Tragedy of Hack Wilson (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000), 85.

4 Ehrgott, 201.

5 Ibid.

6 Parker, 85

7 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Athletics 10

Chicago Cubs 8

Game 4, WS

Shibe Park

Philadelphia, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.