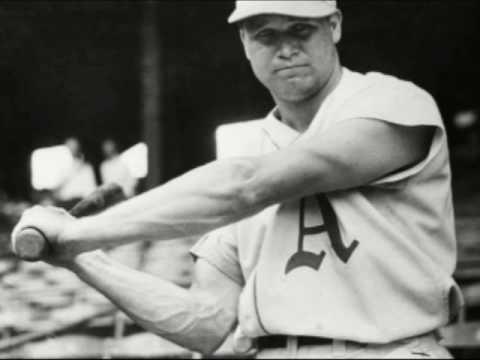

October 6, 1930: Jimmie Foxx’s ninth-inning homer puts A’s on verge of a championship in Game 5

Of all seasons, the least likely in which to expect a pitchers’ duel in the World Series would have been 1930. That year major-league teams scored an average of more than 5½ runs per game, the most for any season since 1896, and nearly 10 percent more than the height of the “steroid era” of the late 1990s and early 2000s. And the offenses of the World Series participants were even more robust: The Philadelphia Athletics averaged nearly 6.2 runs per contest, while the St. Louis Cardinals led the National League with an average of more than 6.5 runs per game and posted a .314 team batting average — pitchers included!

Of all seasons, the least likely in which to expect a pitchers’ duel in the World Series would have been 1930. That year major-league teams scored an average of more than 5½ runs per game, the most for any season since 1896, and nearly 10 percent more than the height of the “steroid era” of the late 1990s and early 2000s. And the offenses of the World Series participants were even more robust: The Philadelphia Athletics averaged nearly 6.2 runs per contest, while the St. Louis Cardinals led the National League with an average of more than 6.5 runs per game and posted a .314 team batting average — pitchers included!

But neither team performed to that standard in the spotlight of the fall classic. The Cardinals scored a total of three runs in losing the first two games of the Series in Philadelphia, and the A’s scored just one run while losing the next two games at Sportsman’s Park.

“It’s the strain of the big show that stops us,” said Cardinals center fielder Taylor Douthit, who hit .303 during the 1930 regular season and .083 in the World Series. “A batter goes up to the plate gripped, trying to bear down, with the result he is not free. A ballgame is different during the season. If we miss we feel we’ll get even the next day. In a World Series we try to get a safe one each time we go to the plate, and we are too tight.”1

Game Five saw both teams struggle at the plate. The Cardinals’ Burleigh Grimes and Philly’s George Earnshaw hooked up in a classic, each allowing just two hits through the first seven scoreless innings.

The Cards had the first scoring opportunity of the day in the third inning. Charlie Gelbert led off with a walk and advanced to second on Grimes’s sacrifice bunt. Douthit hit a groundball to A’s third baseman Jimmy Dykes, whose error the previous day had cost his team the game. Gelbert was halfway to third base and stopped when Dykes fielded the ball. “Dykes chased Gelbert back to second and a throw to [second baseman Max] Bishop would have retired him,” James C. Isaminger wrote in the Philadelphia Inquirer, “but Jimmy, for some reason, never threw at all and charged after Gelbert to tag him. As [Dykes] reached to put the ball on him, Gelbert dived into the keystone and was safe as Dykes sheepishly realized his error of judgment.”2

Douthit reached first on the fielder’s choice, giving the Cardinals two baserunners, but Earnshaw got out of the jam. Sparky Adams popped out and Frankie Frisch was retired when A’s first baseman Jimmie Foxx made a nice play on his sharply hit groundball close to the foul line.

Neither team advanced a runner past first base again until the bottom of the seventh when, with two out, the Cardinals’ Jimmie Wilson got a base hit to center field and stretched it to a double when Mule Haas held onto the ball too long after fielding it and was slow throwing to second. Earnshaw intentionally walked Gelbert to pitch to Grimes, who was not an automatic out; Burleigh batted .263 with the Cardinals in 1930, stroked two hits off Lefty Grove in the first game of the Series and posted a .248 average in his 19-year major-league career. But Grimes was retired on a hard-hit ball to right-center field that Haas tracked down, and the game remained scoreless going into the eighth inning.

That’s when the A’s threatened to finally put a run on the scoreboard. With one out, Haas put down a bunt toward third base and reached on a single when Grimes mishandled it and threw late to first. With Joe Boley at bat, Haas took off for second; Wilson’s throw was in time to retire him and umpire Harry Geisel called him out, but Frisch dropped the ball and Geisel reversed the call, putting a Philadelphia runner on second base for the first time in the game. Frisch threw the ball to the ground and argued that he had held onto the throw long enough, but to no avail. Boley then hit a chopper over Grimes that the pitcher fielded. Haas slid into third ahead of Grimes’s throw, Boley was credited with a single, and the visitors had runners on the corners with one out.

A’s manager Connie Mack then surprised many of those in attendance by removing Earnshaw — who was working on a two-hit shutout and had thrown only 83 pitches — for pinch-hitter Jimmy Moore, who walked on five pitches to load the bases. With the infield in, Bishop hit a groundball to first baseman Jim Bottomley, who threw home to retire Haas on a force out. Dykes followed with a grounder to Gelbert at short for the final out, leaving the game scoreless.

Mack’s choice to pitch the bottom of the eighth was his ace, Lefty Grove — who had thrown 107 pitches the day before in winning Game Four.3 Frisch reached base with a two-out single, but cleanup hitter Bottomley followed with a strikeout, his third of the game. A .304 hitter during the regular season (and .310 lifetime) who was the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1928, Bottomley managed just one hit in 22 at-bats during the Series.

Grimes’s first pitch to Mickey Cochrane leading off the top of the ninth was a ball, but then a called strike and a foul put Grimes ahead in the count 1-and-2 before Cochrane worked out a walk. That brought the dangerous Al Simmons to the plate. Simmons had led the American League with a .381 batting average during the regular season, with 36 home runs and 165 runs batted in. Grimes decided to taunt the slugger.

“When [Simmons] went through a lot of fussy motions, adjusting his cap and sticking his uniform shirt down into his uniform trousers … Grimes gave him the horse laugh,” J. Roy Stockton wrote in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “He gave him more than that. … Grimes openly made fun of Simmons.”4 (An Associated Press account said Grimes had “engaged in a running exchange of insults” with the A’s throughout the game.5)

If Grimes was trying to get into Simmons’s head, it seems to have worked. Simmons swung hard at the first pitch and missed, and then hit a popup into shallow left field that shortstop Gelbert caught. That brought another fearsome hitter to the plate: the 22-year-old Foxx, who had hit 37 home runs and driven in 156 runs during the regular season. When he retired after the 1945 season, Foxx had 534 home runs, second only to Babe Ruth.

Grimes said his first pitch to Foxx was a curve; Foxx said he didn’t see any curve to it. He swung and connected. “The ball soared toward left center,” Stan Baumgartner wrote in the Inquirer. “From the moment it started on its way there was no question as to where it was going to land. [Left fielder] Chick Hafey and Taylor Douthit gave it a half-hearted chase for a few steps, praying that some miracle, some air pocket would halt its flight and bring it down. But they were futile hopes. The speeding apple landed far up in the left center bleachers.”6

Having finally scored against Grimes, the A’s turned the pitcher’s taunts back on him. “As he rounded third, scoring ahead of Foxx, Cochrane put his hands to his ears and waved them derisively at Grimes,” E. Roy Alexander wrote in the Post-Dispatch. “Earnshaw, sitting near Connie Mack on the bench, waved his hand at the Cardinal pitcher in a gesture of contempt. Joe Boley and Bing Miller ran out from the bench and danced a few steps, concluding their performance by giving Grimes a Bronx cheer.”7

Back in Philadelphia, A’s fan George McQuilkin heard Foxx’s home run on the radio broadcast of the game just as his wife, Adelaide, was delivering an 8-pound boy. In honor of the occasion, the McQuilkins named their son James Foxx McQuilkin.8

Given a two-run lead, Grove didn’t squander it. Pinch-hitter Ray Blades walked with one out in the bottom of the ninth, but Grove retired Wilson on a groundball and struck out Gelbert to give the A’s a three-games-to-two lead in the series. The Cardinals never got a runner as far as third base in the game.

The A’s won their second straight championship two days later back in Philadelphia, when Earnshaw — pitching on one day’s rest — beat the Cards, 7-1. (Earnshaw had also started consecutive games in the 1929 World Series. No pitcher did that again in the fall classic until 2018.) One year later Grimes and Earnshaw would meet again at Sportsman’s Park, this time in Game Seven of the World Series — and with a different result.

This article appears in “Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis: Home of the Browns and Cardinals at Grand and Dodier” (SABR, 2017), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. Click here to read more articles from this book online.

Sources

Game stories in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, St. Louis Star, and Philadelphia Inquirer were accessed via Newspapers.com. Stories in The Sporting News were accessed via PaperofRecord.com.

Notes

1 Sid Keener, “Sid Keener’s Column,” St. Louis Star, October 7, 1930: 16.

2 James C. Isaminger, “Foxx’ Homer in Ninth Beats Cardinals 2 to 0 and Gives Macks Series Lead,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 7, 1930: 22.

3 Pitch counts for Game Four are in the Philadelphia Inquirer, October 6, 1930: 14. Pitch counts for Game Five are in the Philadelphia Inquirer, October 7, 1930: 23.

4 J. Roy Stockton, “Grimes Has His Fun With Simmons; Foxx Breaks It Up With Home Run,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 7, 1930: 14.

5 Associated Press, “Grimes Dusts Al Three Times in 4th,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 7, 1930: 22.

6 Stan Baumgartner, “Foxx Goat One Day and Hero the Next as A’s Forge Ahead,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 7, 1930: 22.

7 E. Roy Alexander, “Crowd on Edge Watching Duel of Pitchers,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 7, 1930: 14.

8 Dora Lurie, “Parents to Name New Heir After A’s Slugger,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 7, 1930: 24. James Foxx McQuilkin died in 2003. His death date and his mother’s first name were found on Ancestry.com.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Athletics 2

St. Louis Cardinals 0

Game 5, WS

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.