October 7, 1952: Billy Martin saves the Series

The 1952 World Series was the fourth straight for the New York Yankees and the third in six seasons for the Brooklyn Dodgers. The teams had met in the last Game Seven, in 1947, with the Yankees winning—a familiar outcome. In 1952, New York was looking for its 15th world championship, the Dodgers, seemingly as ever, for their first.

Joe DiMaggio was gone, with Mickey Mantle moving from right field to take his place in center. DiMaggio had played in 10 World Series with the Yankees, but in only one that went to a seventh game. That was still one more than DiMaggio’s long-time teammate, Bill Dickey, who had played in eight World Series. He was participating in his first Game Seven in 1952—as a coach.

Another man taking part in his first seventh game was Casey Stengel, the New York manager. Stengel had played in three World Series, two of them against the Yankees, and managed in three, winning all of them, since becoming manager of the team in 1949. Under Stengel, the Yankees beat Brooklyn in five games in 1949, Philadelphia in four games in 1950, and the New York Giants in six games in 1951.

In 1952, however, the Yankees had a greater challenge and trailed after five games as the Series shifted from Yankee Stadium back to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. Despite two home runs by the Dodgers’ Duke Snider, New York won the sixth game. In doing so, Stengel had to upset his pitching plans, calling on Allie Reynolds—whom he planned to start in the seventh game—in relief of his starter, Vic Raschi. As a result, Stengel was undecided on a starter for the seventh game.

On the other hand, everything remained in place for Brooklyn manager Chuck Dressen and his pitcher of choice for the World Series finale, Joe Black. Black had pitched eight seasons with the Baltimore Elite Giants in the Negro National and Negro American leagues before spending the 1951 season with Montreal in the International League and St. Paul in the American Association. Black became a 28-year-old rookie with Brooklyn in 1952 and was the Dodgers’ relief ace, compiling a 14-3 record out of the bullpen. He added a win and a loss as a starter late in the season, part of Dressen’s plan to rely on Black in the World Series. Dressen worked out the timing of Black’s starts so that he could be the starting pitcher in the series opener on Wednesday, October 1. Black won that game but was the losing pitcher in the fourth game on Saturday, October 4, despite giving up only one run and three hits in seven innings. Dressen had said he might use Black both as a starter and reliever in the series, and Black warmed up in the bullpen during the fifth game, but didn’t come in. He stayed exclusively a starting pitcher.

With the World Series taking place entirely within one city, no travel off-days were necessary, and the series was played on consecutive dates, meaning that Black had only two days of rests between his starts. In the first and fourth games, Black had pitched against Reynolds, and the two would have met again if not for Reynolds’s relief stint the day before.

Stengel considered rookie Tom Gorman, who had made one relief appearance in the series, before finally settling on left-hander Eddie Lopat, who had pitched 8 1/3 innings in losing the third game, four days before. Stengel didn’t make his decision on a starter until 11:30, fewer than two hours before the game. “I had 55 reasons why I should not start Lopat, but I had 56 reasons why I should,” explained Stengel, although the loquacious Case did not follow up with a Stengelese elaboration on those reasons.1

The Yankee team bus drew a police escort from Yankee Stadium to Ebbets Field, but partway there, a candy red sports car joined the motorcade. A motorcycle cop in the escort dropped back to tell the driver to buzz off, but it turned out to be Phil Rizzuto, who chose to drive himself from his New Jersey home to his native Brooklyn.

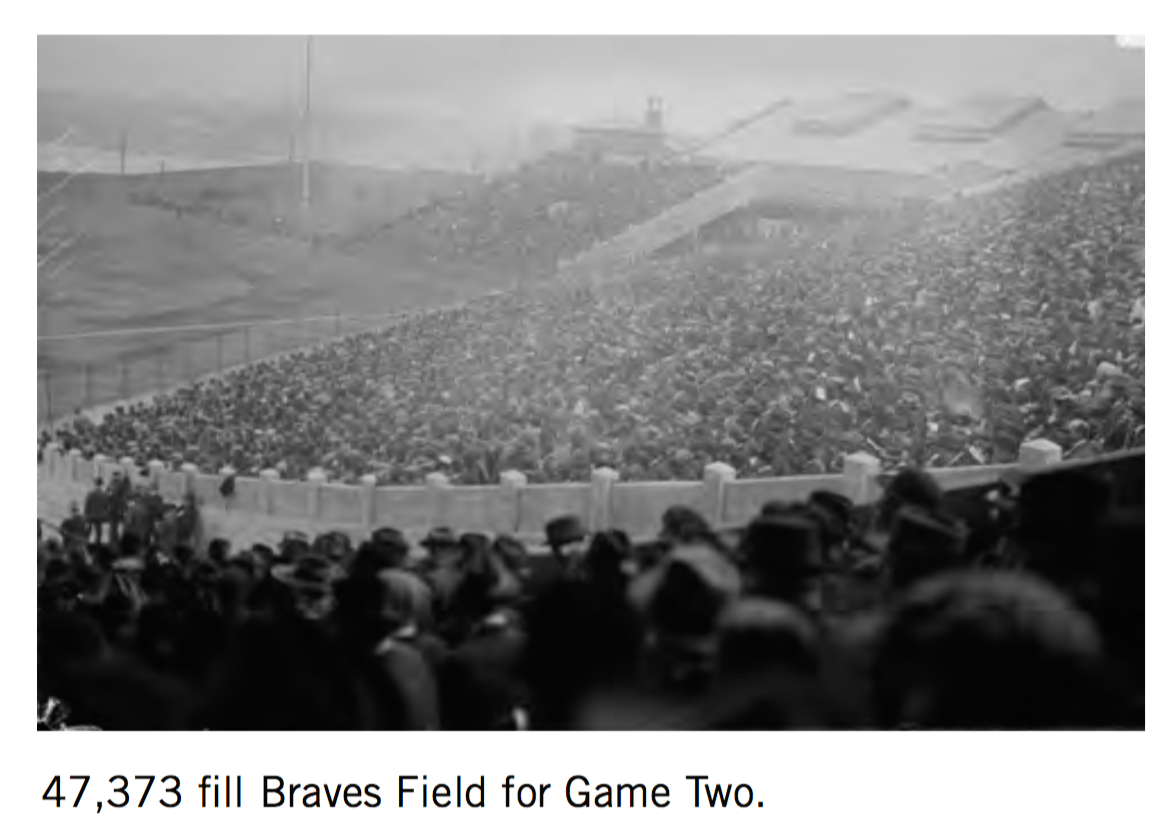

Ebbets Field was full for Game Seven, unlike the sixth game when the attendance was several thousand short of capacity. The Dodgers sold tickets for each game individually instead of in blocks, as the Yankees had done. As a result, Brooklyn found itself with unpurchased tickets for the sixth game. However, when it was clear that the entire Series would come down to one game, long lines of ticket buyers circled Ebbets Field through the evening following the sixth game and on the morning of the seventh game.

Neither team got a runner past first base through the first three innings. Black retired the Yankees in order in the first, walked lead-off hitter Johnny Mize before retiring the next three batters on fly outs in the second, and then put the Yankees down without a runner in the third.

Lopat was equally effective over that span, although he got a couple breaks in the first inning. With one out, Pee Wee Reese reached first on a throwing error by third baseman Gil McDougald. However, had McDougald’s throw not struck Brooklyn first-base coach Jake Pitler, Reese likely would have ended up on second. With two out, Jackie Robinson hit a hard liner to left-center. Gene Woodling raced to his left to make the catch and save a run. Lopat allowed a two-out single to George “Shotgun” Shuba in the second and retired the Dodgers in order in the third.

Phil Rizzuto led off the top of the fourth with the Yankees’ first hit, a double inside the third-base bag, and went to third on a ground out by Mantle. John Mize stepped up and hit a hard drive to right that hooked foul, then went the opposite way with a line-drive single to bring home Rizzuto. Yogi Berra grounded into a double play to end the inning, but the Yankees had a 1-0 lead.

The lead didn’t last long as Lopat was unable to retire a batter in the bottom of the fourth. Snider opened with a single, and Jackie Robinson put down a bunt, intending to sacrifice Snider to second. Robinson’s bunt, down the third-base line, was so well-placed that he also reached safely. Roy Campanella followed with the same intention, a bunt designed to move up the runners, and likewise ended up with a hit, filling the bases.

This was enough for Stengel, who brought in the man he had decided not to start, Allie Reynolds, to face the right-handed hitting Gil Hodges. Hodges had endured a miserable series. He was hitless in 17 at-bats through the first six games. He had struck out three times before being lifted for a pinch-hitter in the sixth game and had flied out his first time up in Game Seven. Against Reynolds, Hodges flied out again, but it was deep enough to bring home Snider with the tying run. (Although Hodges got a run batted in, he was charged with an at-bat on the play, as it wasn’t until 1954 that the practice resumed of awarding a sacrifice fly—with no at-bat charged—for a run-scoring fly ball.)

In addition to Snider scoring on Hodges’ fly, Robinson took third as Reynolds fumbled Woodling’s throw to the plate. Robinson stayed at third, though, when Shuba struck out and Carl Furillo grounded to McDougald to end the inning.

Woodling quickly put the Yankees back in front, opening the fifth with a home run onto Bedford Avenue, beyond the right-field fence. Joe Black told reporters, “My curve spun but it didn’t move.”2 The Dodgers came back again, tying the score on a one-out double off the fence in right-center by Billy Cox and a single to left by Reese. Cox scored on the hit, and Reese went to second as Woodling uncorked a wild throw. Snider grounded out, sending Reese to third, and Robinson ripped a liner toward left that McDougald speared for the third out to prevent Brooklyn from taking the lead.

Instead, the Yankees got the go-ahead run in the top of the sixth. After Rizzuto lined out, Mantle hit a towering home run to right-center. A single by Mize finished off Black, who gave way to Preacher Roe. With another hit and an error, New York loaded the bases, but Roe got out of the inning without any more damage.

Campanella started the last of the sixth with a single but was wiped out as the hitless Hodges grounded into a double play. Shuba grounded out to end the sixth with the Dodgers down by a run.

New York made it a two-run margin in the seventh, scoring a single run for the fourth inning in a row, as Mantle singled in McDougald from second with two out. Reynolds had been removed for a pinch-hitter in that inning, and Vic Raschi, who had pitched 7 2/3 innings the day before, was on the mound for the last of the seventh. Raschi walked Furillo but got Rocky Nelson, hitting for Roe, to pop out. Cox came through with a single and Reese walked to load the bases. With the left-handed hitting Snider up next, Stengel called for southpaw Bob Kuzava. A year before, against the New York Giants, Kuzava had saved the final game of the World Series, but he had seen little action during the final weeks of the 1952 season.

Snider worked the count full, then popped out when Kuzava handcuffed him with an inside fastball. “The pitch was right down the middle,” Kuzava told reporters later. “The type that Snider could powder a mile.”3 With Johnny Sain warming up in the New York bullpen, Kuzava thought he would be lifted. Stengel even started toward the mound, but then changed his mind and returned to the dugout, leaving Kuzava in to face Jackie Robinson. Like Snider, Jackie Robinson popped up. Robinson’s fly, however, became anything but routine. “Nobody told me he (Kuzava) could break it off that good,” Robinson later said of Kuzava’s curve.4

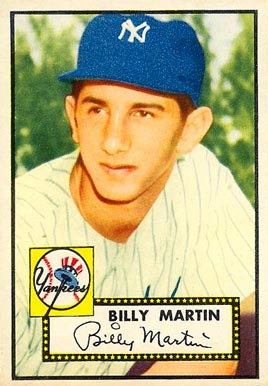

First baseman Joe Collins lost sight of ball in the sun, leaving it to second baseman Billy Martin. Collins thought it was a foul ball in the stands. Martin knew otherwise. As Martin moved in for the catch, a gusting wind pulled the ball back to the plate. Martin sped up, lunged, and caught the ball about two feet off the ground, ending the inning. “He ran out from under his hat and almost ran out of his shoes in a breakneck lunge,” wrote Arthur Daley in the New York Times.5

The play was greeted with a lack of sympathy for Collins and Martin. Stengel yelled at Collins, “Wake up out there,” while Yankee General Manager George Weiss, sitting in the team’s field box, and never a fan of Billy, sneered, “Little show-off. He made an easy play look hard.” Martin himself didn’t realize how tough the catch was until he saw the films after the game.6

Accounts differ as to what the impact would have been had the ball dropped safely. Some versions of the play claim the count to Robinson was 3-2, meaning that the runners would have been going on the pitch and give some credence to the claim that three runs might have scored, giving the Dodgers the lead. Stan Baumgartner, in the 1953 The Sporting News Baseball Guide, also said the count was 3-2. However, the game story by Dan Daniel (writing under the byline “Daniel”) in the New York World-Telegram and Red Smith’s column in the New York Herald-Tribune both give the count as two balls and two strikes. As for Kuzava, he recalls that the count was 2-2 but that, even with the runners not going on the pitch, “they all would have scored.”7

Kuzava was correct about the count, confirmed by a full-game broadcast now available. (The pitch sequence to Robinson was foul, ball, ball, foul, foul, pop up.) However, the video also shows Reese just around second when the ball was caught, and it is clear that he would not have scored. Regardless of how many runs would have come home on the play, the Yankees’ lead would have been wiped out. But Martin, with his grab, prevented that from happening.

It was the Dodgers’ last threat. Hodges got to first on an error with one out in the eighth (his 21st at-bat without a hit in the series), but Kuzava allowed no more baserunners, retiring the final five Dodgers in the eighth and ninth innings, and New York had a 4-2 win, and the World Championship.

Gloomy Dodger fans endured the final innings. After the game, Dodger organist Gladys Gooding serenaded them with a medley of appropriate songs, which included “Blues in the Night,” “What Can I Say, Dear, After I Say I’m Sorry,” “This Nearly Was Mine,” “What a Difference A Day Makes,” and finally, “Auld Lang Syne.”

Casey Stengel explained the victory in typical fashion: “Them Brooklyns is a little tough in this park,” he said. “But I knew we would win today. My men play good ball on the road. Now, you are gonna ask me why I left in the left-hand fella [Kuzava] to face the right-hand fella [Robinson], who makes speeches, with bases full. Don’t I know percentages and et cetera? The reason I left him in is the other man [Robinson] has not seen hard-throwing left-hand pitchers much and could have trouble with the break of a left-hander’s hard curve, which is what happened.”8

For Mickey Mantle, who had the game-winning home run, the end of the season meant a return to the mines. “I’ve had enough excitement for one season,” he told the United Press, “so I’m going right back to work in the lead and zinc mines of Oklahoma, where things are a little more quiet.”9 He added that he had seven dependents to care for: three brothers, a sister, his mother, his wife, and a baby due in March.

For Casey Stengel, the win allowed him to join Joe McCarthy as the only manager to win four consecutive World Series. McCarthy did it with New York in 1936 to 1939, the Yankees not even having to go to a seventh game in any of those years.

Stengel topped McCarthy when New York won the World Series again in 1953, once again beating the Dodgers, this time in six games. The Yankees, with 19 pennants and 15 World Series championships since 1921, were in the midst of their greatest dominance. However, they would encounter a few bumps, along with several more Game Sevens, during its dynasty.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

NOTES

1 Louis Effrat, “Dodgers’ Organist Plays the ‘Blues,” New York Times, Wednesday, October 8, 1952: 38.

2 Cecilia Tan, 50 Greatest Yankees Games in Yankee History, (Hoboken: Wiley and Sons, 2005), 83.

3 Tan, 84.

4 Tan, 84.

5 Tan, 84.

6 Peter Golenbock, Wild, High, and Tight: The Life and Death of Billy Martin (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994), 72 and 73.

7 Author’s interview with Bob Kuzava, September 29, 2002.

8 Roger Kahn, The Era, 1947-1957, (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1993), 308.

9 “Mantle to Return to Peace of Mine” by Mickey Mantle, as told to The United Press, New York Times, Wednesday, October 8, 1952: 38.

Additional Stats

New York Yankees 4

Brooklyn Dodgers 2

Game 7, WS

Ebbets Field

Brooklyn, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.