September 17, 1993: Expos fans shower Curtis Pride with cheers after first hit

Baseball fans feel many emotions during the course of a game. They may feel joy, anger, euphoria, or despair. But rarely, if ever, does a single, ordinary play become a moving, lump-in-your-throat memorable event. It did on this night.

Baseball fans feel many emotions during the course of a game. They may feel joy, anger, euphoria, or despair. But rarely, if ever, does a single, ordinary play become a moving, lump-in-your-throat memorable event. It did on this night.

The 45,757 fans who attended the game at Olympic Stadium on September 17, 1993, felt all of these emotions and more as they watched the Expos roller-coaster their way to a thrilling 8-7 win over the Philadelphia Phillies in the heat of the pennant race. And they took to their hearts a 24-year-old minor-leaguer named Curtis Pride as they saw him get his first major-league hit and acknowledge their thunderous applause — even though he couldn’t hear it.

The Expos were so hot when play began that night that you could have fried a proverbial egg on them. After losing 4-2 to Cincinnati on August 20, the Expos were in third place in the National League East, at 64-59, 14½ games in back of Philadelphia. They then went on a 20-3 run, and at the start of play on September 17 the Phillies (89-57) were five games up on Montreal (84-62). The two teams were looking over their shoulders only to wave goodbye to the rest of the division.

Ben Rivera started for the Phillies. He had a 12-9 record going into the game; he had been hammered for five runs (four earned) in his previous start, a 9-2 loss to the Houston Astros on September 12. Dennis “El Presidente” Martinez (14-8) was his mound opponent. He had pitched well in his previous start, a no-decision against Cincinnati, in which he gave up only one run over seven innings in a 3-2 Expos win.

The crowd, the quality of the teams, and the tension of the pennant race all promised a tight, close ballgame, and that’s how it went — at least in the beginning. The game was scoreless until the bottom of the fourth, when the fastest team in baseball — the Expos led the National League in stolen bases that year with 228 — walked their way to their first run of the game. Larry Walker singled to center, but was forced out at second on a Darrin Fletcher fielder’s choice. Fletcher then paraded around the bases to third after walks to Randy Ready and Wil Cordero, and scored when Rivera walked Martinez.

The Expos built on their 1-0 lead in the fifth. Rivera started the inning by issuing his fifth free pass of the game, this time to Delino DeShields. DeShields took all these walks as a personal insult, so he showed off some team speed by stealing second. He moved to third on a sacrifice bunt by Rondell White and scored on Walker’s single. Walker himself moved to third on a Fletcher single, and that was it for Rivera. Roger Mason replaced him, and started off by — you guessed it — walking the first hitter he faced, Randy Ready. Sean Berry hit a sacrifice fly to score Walker and the Expos led 3-0.

The usually reliable Martinez, who gave up only three hits in the first five innings, fell apart in the sixth. Mariano Duncan started the inning with a single and moved to third on John Kruk’s double. After Dave Hollins struck out, Darren Daulton smacked his 24th home run of the year, which tied the game at 3-3, but the Phillies’ barrage was just beginning.

Martinez’s first pitch to Jim Eisenreich found its way down the left-field line; Eisenreich headed to second and Martinez headed to the showers. Mel Rojas came in and was victimized by bad luck when Ready didn’t live up to his name and made an error on Milt Thompson’s grounder. Rojas didn’t do nepotism’s reputation any favors — Expos manager Felipe Alou was his uncle — by walking Kevin Stocker and pinch-hitter Mickey Morandini to score Eisenreich with the go-ahead run. A sacrifice fly by Lenny Dykstra and a two-run double by Duncan completed the carnage. It was 7-3 Phillies after 5½ innings.

The Expos got one back in the bottom of the inning off Bobby Thigpen. With two out DeShields cracked a single to center. White hit an ordinary fly that Dykstra caught in center for the third out, yet nobody left the field. It turns out that Thigpen had balked on the play, sending DeShields to second. White then singled to center, scoring DeShields and making it 7-4.1

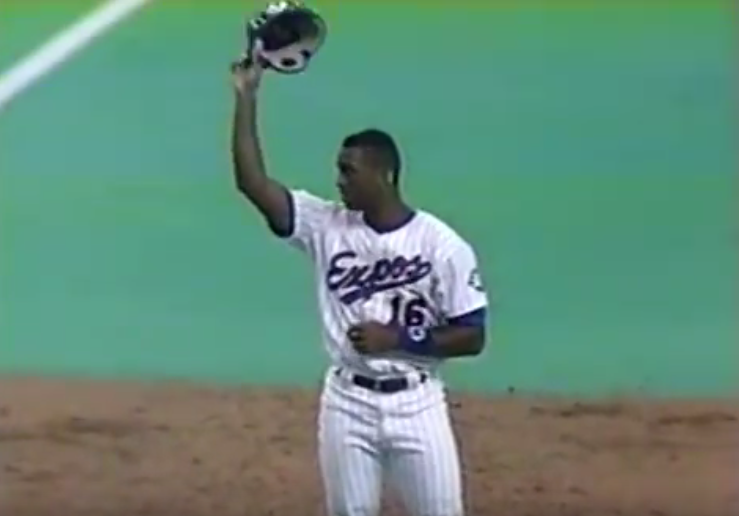

The bottom of the seventh started routinely enough. Fletcher singled and was forced at second on a Ready grounder. Berry beat out a high chopper to third and, with two runners on, Alou sent Pride up to pinch-hit for pitcher Chris Nabholz, who had come on with two out in the sixth. This is the moment when this became more than just a ballgame.

We are all inspired by the resiliency of the human spirit. Everyone loves to see people succeed after overcoming a physical or mental disability, especially in professional sports. Pride was born deaf, was a multi-sport athlete — he was named one of the top 15 youth soccer players in the world in 1985 — and graduated from the College of William and Mary in 1990 with a degree in finance. When he made his Expos debut on September 14, he became the first hearing-impaired major leaguer since Dick Sipek, who played 85 games for the Cincinnati Reds in 1945.

Pride received the same polite applause when he was announced into the game that any other pinch-hitter would get. Thigpen threw his first pitch, and Pride swung and sent a liner to the gap in left-center for a double that scored two runs. Naturally the hometown crowd stood to cheer. Phillies manager Jim Fregosi came out to change pitchers, and while that was going on, Expos third-base coach Jerry Manuel walked over to Pride and through gestures got him to remove his batting helmet to acknowledge the crowd. The cheering got louder and continued all through Larry Andersen’s warm-up tosses.

“The way they kept cheering, it’s as if the crowd wanted to break a barrier,” said Manuel after the game. “They wanted him to know how they felt, to get beyond the wall. That’s the greatest thing I’ve ever seen.”2

Not only was it emotional, it was also clutch because it brought the Expos back to within a run with a runner on second and only one out. The Expos tied the game at 7-7 when Marquis Grissom singled Pride home. Olympic Stadium was a happy nuthouse.

From that point on it became a war of attrition. The Expos almost took the lead in the eighth when they had the bases loaded with one out, but Sean Berry hit into an inning-ending double play. No one scored in the ninth, 10th, or 11th. Finally, with Mitch “Wild Thing” Williams on the mound in the 12th, Grissom doubled, stole third, and incited fan pandemonium when he scored on a DeShields sacrifice fly.

The victory brought the Expos to within four games of the Phillies, but for all intents and purposes they never got any closer. A 3-1 victory over Pittsburgh on the last day of the season brought them within three games of Philadelphia, but that was too little, too late. There was, however, lots of room for optimism. The team went 46-28 after the All-Star break and that record was a harbinger of things to come in 1994; that season they had the best record in baseball when the players strike wiped out the remainder of the season and the World Series.

As for Pride, he never really caught on at the major-league level, playing only 421 games for six different teams. He finished with a .250 career batting average, 20 home runs, and 82 RBIs, but his numbers didn’t prevent his efforts from being acknowledged for his courage. In 1996 he won the Tony Conigliaro Award, which is given annually to a major-league player “who best overcomes a major, often life-altering obstacle and continues to thrive through adversity.”

Pride continued working with the deaf after his playing career in many capacities, including as baseball coach at Gallaudet University, a school specifically for hearing-impaired students, and with his Together With Pride Foundation, which operates programs for hearing-impaired children.3 Pride’s contributions and achievements were even recognized at the highest levels, when President Barack Obama named him to the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports, and Nutrition in 2010.

This article appeared in “Au jeu/Play Ball: The 50 Greatest Games in the History of the Montreal Expos” (SABR, 2016), edited by Norm King. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author consulted:

Baseball-reference.com.

Baseball-almanac.com.

Fitness.gov.

Gallaudet.edu.

Redeafined Magazine.

Togetherwithpride.com.

YouTube.com.

Box scores for this game can be found on baseball-reference.com, and retrosheet.org at:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/MON/MON199309170.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1993/B09170MON1993.htm

Notes

2 Jonah Keri, Up, Up & Away, The Kid, The Hawk, Rock, Vladi, Pedro, Le Grand Orange, Youppi!, The Crazy Business of Baseball & the Ill-Fated but Unforgettable Montreal Expos (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2014).

3 He was still the Gallaudet baseball coach as of 2015.

Additional Stats

Montreal Expos 8

Philadelphia Phillies 7

12 innings

Olympic Stadium

Montreal, QC

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.