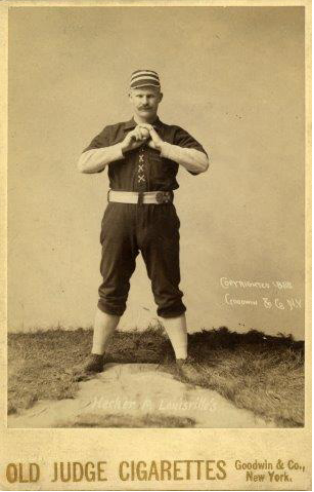

September 19, 1882: Guy Hecker throws Louisville’s second no-hitter of season

When Guy Hecker tossed a no-hitter against the Alleghenys of Pittsburgh on September 19, 1882, it was a first in several ways:

When Guy Hecker tossed a no-hitter against the Alleghenys of Pittsburgh on September 19, 1882, it was a first in several ways:

- It was the first time the losing team scored a run in a no-hitter.

- It was the first time a team recorded a second no-hitter for the franchise.

- It was the first time a team recorded two no-hitters in a single season.

Eight days earlier, Hecker’s Louisville teammate Tony Mullane had pitched Louisville’s first no-hitter, against Cincinnati. Mullane’s game was the first American Association no-hitter and matched the previous five no-hitters tossed by National League pitchers. It was also the first no-hitter thrown from the new 50-foot pitching distance. Mullane and Hecker had a long-running association. After playing one season for a professional team in Springfield, Ohio, Hecker returned home to Oil City, Pennsylvania, to get married and join the local labor force. He continued to play with local semipro teams and in 1879 Tony Mullane joined his Oil City team. When Mullane signed with Louisville for the 1882 season he recommended Hecker to the management for the position of change pitcher. Hecker was signed and primarily played first base, pitching in 13 games in 1882.

Hecker’s sixth start of the season was at Pittsburgh’s Exposition Park on September 19, 1882. Neither team was more than a middle-of-the-pack squad at this point of the season. The Alleghenys entered the game in fourth place with a 37-36 record. Louisville was slightly better at 37-32 in second place. But it was mostly academic as Cincinnati had clinched the pennant the day before. The Allegheny team was a solid hitting team with Ed Swartwood being the most productive batter. Swartwood led the American Association that season in total bases (161); runs scored (87), and doubles (18). He was third in batting average (.331), second in slugging average (.498), tied for second in hits (109), and third in home runs (4). The Association’s premier batter that season was on the other side. Pete Browning won the batting (.378) and slugging (.510) titles and finished second in home runs (5) while tieing Swartwood for second in hits (109). Hecker’s mound opponent was Denny Driscoll. Driscoll was signed by the Alleghenys in June and developed into the second starter behind Harry Salisbury. Driscoll posted a 13-9 record with a league-leading 1.21 ERA.

Both pitchers were effective and the game was scoreless through the fifth. Driscoll retired Leech Maskrey to open the sixth inning and then walked John Reccius. At this point in the reporting on the game one runs into a chronic problem with recording events in 19th-century baseball. Each reporter of a game kept his own scorecard. The assignment of hits, errors, and other scoring decisions can and does vary from one paper to another. With Reccius on second and one out, Browning came to the plate and either singled home Reccius after Reccius stole second with Browning advancing to second on an error by Mike Mansell, or Reccius scored on Browning’s double. The consensus of the Pittsburgh writers (the Louisville paper’s stories were dispatches by Pittsburgh writers) was that Browning doubled Reccius home with the first run of the game. Hecker followed Browning with an RBI single and Louisville was up 2-0 entering the bottom of the sixth.

The scoring confusion continued in the bottom of the sixth. With two outs Swartwood lifted a fly ball to left-center. Reccius misplayed the fly and then threw wildly to second, with the ball skipping past all the fielders and allowing Swartwood to score. Or after Reccius muffed the fly, center fielder Maskrey threw wildly to the infield or Maskrey’s throw was misplayed by second baseman Denny Mack, allowing Swartwood to score. The reporting consensus was that Reccius committed a pair of errors on the play.

The scoring differences of opinion popped up again in the top of the seventh. Mack singled to open the inning and was forced at second by Mullane. Then either Mullane stole second and scored from second on a routine groundout to shortstop or … when Mack was forced at second, George Strief tried to complete the double play and threw wildly to first, putting Mullane on third, from where he scored on Schenck’s groundout to short. As it seems improbable that Mullane scored from second on a routine groundball, it is more likely that Strief’s error put him on third. From this point, each team was retired in order through the end of the game.

The final scoring discrepancy questions the number of hits Hecker surrendered. According to the Pittsburgh Telegraph, Pittsburgh Commercial-Gazette, Pittsburgh Times and the Louisville Commercial, it was a no-hitter. But Louisville’s Courier-Journal records one hit for Pittsburgh. As with all the other variances, only the Courier-Journal deviates from the consensus of all the other papers. The Courier-Journal credits Pittsburgh shortstop John Peters with a single. There are two possibilities where this might have happened. In the fifth and seventh innings, Peters reached base on what were reported as Browning errors at shortstop. But the Courier-Journal box score records a pair of errors charged to Browning and the Commercial-Gazette and Pittsburgh Times game stories give no other situation where Browning might have picked up an error. Since the Courier-Journal is the sole source for all the scoring questions, it is likely that the correspondent who sent the paper the Pittsburgh game story was either unfamiliar with scoring a game or had a different set of standards to judge scoring decisions. In any case, treating the Courier-Journal as an outlier among the five papers consulted, Hecker gets his no-hitter.

Although Hecker’s feat was acknowledged as worthy of note in the game stories, it was still just a single game with no future reference to it later in the week or later in the season. The Reach and Spalding Guides that cover the 1882 season make no reference to any no-hitter recorded in 1882. The Pittsburgh Times noted that no hits were made off Hecker in a sub-headline, but no other papers made any reference to it until late in their game story. In the last sentence of the story, the Times wrote, “The home nine failed to get a base hit off Hecker during the entire game. …”

The Louisville Commercial said, “Not one base hit was scored by them [Pittsburgh]. …”

The term no-hitter appears in no story about the game.

Skip McAfee, editor of the Dickson Baseball Dictionary, notes that the earliest reference he knows for the use of the term “no-hitter” is in a story appearing in the Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening News on August 31, 1911. No-hitters in the 19th century were viewed neither by fans nor sportswriters as the sort of significant events they became in later years. By and large, they were just another ballgame.

The various difficulties in dealing with the reporting and scoring of this game underscore the challenges faced by 19th-century researchers to assemble accurate statistics for the period. Even with multiple contemporary newspaper sources, we cannot determine with much confidence the details of many games played. We only have the comfort that scoring decisions do not change the outcome of the games.

Four years later, Hecker also achieved note when he homered three times in one game, and set single-game records for runs scored (7), total bases (15), and home runs (3), in the August 15, 1886, game for Louisville.1

This article was published in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin. To read more Games Project stories from this book, click here.

Sources

Courier-Journal (Louisville), Louisville Commercial, New York Clipper, Pittsburgh Commercial-Gazette, Pittsburgh Times, and Pittsburgh Telegraph, all dated September 20, 1882.

Bevis, Charlie. “Denny Driscoll,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org/bioproj/person/c7e1352a.

Bailey, Bob. “Guy Hecker,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org/bioproj/person/4b471b76

Thanks to Bruce Allardice, Craig Britcher, Gary Collard, Bob LeMoine, Tom Mueller, Ron Selter, Andrew Terrick, and Bob Tholkes for their assistance to gather Pittsburgh newspaper stories on the game. Thanks to Skip McAfee for his help on the use of the term “no-hitter.”

Notes

1 Bob Bailey, “August 15, 1886: Guy Hecker: hitting pitcher,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/august-15-1886-guy-hecker-hitting-pitcher.

Additional Stats

Louisville Colonels 3

Pittsburgh Alleghenys 1

Exhibition Park

Pittsburgh, PA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.