September 20, 1893: Beaneaters clinch NL pennant, earn ‘proud emblem to wave here next year’

The first frost would not arrive in Cleveland for another six days. Two thousand fans officially attended the pennant-clinching game against the defending champion Beaneaters. The attendance, slightly above average, was pretty respectable for a fall Wednesday afternoon game in northern Ohio when the home team’s pennant chances were long gone.

The first frost would not arrive in Cleveland for another six days. Two thousand fans officially attended the pennant-clinching game against the defending champion Beaneaters. The attendance, slightly above average, was pretty respectable for a fall Wednesday afternoon game in northern Ohio when the home team’s pennant chances were long gone.

Because the Spiders departed from baseball history in such an ignominious way in 1899, with their 20-134 record still being the worst in major-league annals, it is easy to forget that they were once a very good team.

In 1892 Cleveland had narrowly lost to Boston in a playoff between the split-season champions. While a team with Cupid at second, Virtue at first, and Patsy at third – not to mention Chief Zimmer at catcher who was not an Indian from Cleveland or anywhere – deserves to be good, any team with Denton True Young was going to be competitive.

Cy as he was called, was not quite as good in 1893 as he had been in 1892, winning only 34 games (which was still nearly half the team’s wins). Having pitched the day before and with Cleveland headed for a third-place finish, Cy was not on the mound this day. Instead, Cleveland debuted a rookie who just arrived from the Buffalo Bisons of the Eastern League.

Chauncey Burr Fisher was from Anderson, Indiana. His nickname was Whoa Bill. His brother Thomas Chalmers Fisher, eight years younger, made his major-league debut in 1904 as a member of the Boston Beaneaters.1 Chauncey Fisher was only 21, and already had pitched 416 innings that year for the combination of the lower-level Easton Dutchmen of the Pennsylvania State League and Buffalo. So he wasn’t exactly a fresh arm.

Facing off with Fisher was 25-year-old Jack Stivetts. He was no slacker either, having pitched over 400 innings in each of the previous three seasons, though he was comparatively rested for this game since he hurled only 300 innings in 1893. Stivetts had been the Beaneaters’ co-ace until the younger Kid Nichols moved ahead of him as the team’s top pitcher in 1893.

Archrival Cleveland would rather have had Boston clinch its third championship in a row somewhere other than League Park, so the Spiders were determined to put up a fight. During the game the proceedings from Brooklyn’s defeat of Pittsburgh were posted so, as one reporter noted, “The champions figured that if they won they would have the pennant in their fingers, so they went after it, and how they did go.”2

The Boston Globe’s game article proclaimed: “Pennant Comes to Boston, Cleveland Put Up Grand Ball But the Bostons ‘Got There.’” In other words, two pretty tired pitchers engaged in a hard-fought gritty game of “scientific baseball.”3

The New York Clipper’s summary of Boston’s triumph at the week’s end stated and restated the same point. Boston was not an “aggregate of stars” but a “well-balanced body of team workers.” The Beaneaters didn’t work to “advance their own records” and their manager, Frank Selee, was “clever and shrewd.” Even more bluntly, the Clipper wrote that “ball players are not as a rule gifted with over much brain power” so Selee basically had to outsmart the opponents.4

Timothy Murnane had been a decent ballplayer but earned even greater fame for his 30 years as a sportswriter for the Globe.5 In both his year-end summary and the game summary, Murnane used the term “scientific ball,” stating that “the exhibition of fine scientific work, both in the field and at the bat of the Boston players, has been a revelation to the baseball patrons, not only in Boston, but in each of the 11 other cities in the League.”6 Murnane included detailed statistics highlighting that Boston did not have the league leaders in the traditional hitting categories. The team utilized bunts, stealing bases, good fielding, solid pitching, and timely hitting to win games. His 1893 analysis was almost like a SABR conference presentation in 2017.

The September 20 game was not untypical of the season. Neither team could get a run across the plate for the first five innings. In inning six the relative floodgates opened as ballplayers were jamming the bases.

Boston scored three runs in the top of the sixth. Billy Nash, the team captain, was one of the Beaneaters’ sluggers. He finished eighth in the NL with 10 home runs in 1893. In this game, Nash was Boston’s primary slugger, hitting two doubles to go with the team’s flood of singles. But Nash also understood so-called “scientific” baseball. He led off the sixth inning by drawing a walk. Then he stole second, and Boston was on its way.

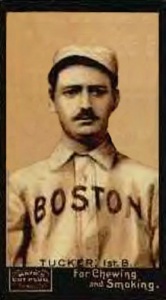

Next up was Tommy Tucker, a mini-celebrity because of his name. For example, the Boston Post reporter couldn’t resist, when noting that Fisher was debuting in this game, writing that “Cleveland wanted to try him on Boston because they thought if he could stand Tommy Tucker crying for his supper, he could stand anything.”7 Tucker earned his supper, beating out a bunt.

Then Chief Zimmer allowed a passed ball, which sent Nash to third and Tucker to second.

Charlie Ganzel grounded out to Cupid Childs at second, holding the runners. Pitcher Stivetts, batting seventh instead of ninth in the order, hit the ball to shortstop Ed McKean, who “fired the ball home to catch Nash.”8 Zimmer, who was not having a good inning, dropped the ball. 1-0, Stivetts to first base. The next Boston batter, Cliff Carroll, bunted, scoring Tommy Tucker. 2-0, Stivetts to second. Charlie Bennett stuck out but then shortstop Herman Long singled, scoring Stivetts. Suddenly it was 3-0 on a single, two bunts, a passed ball, an error by the catcher, and a stolen base.

Cleveland slugged its way right back into the game. The first batter made an out, but the next singled and went to second on a poor throw by Boston second baseman Bobby Lowe. A single scored Cleveland’s first run. Spider Ed McKean doubled, moving the runner to third. Then Virtue came to the plate. Jack, as he was known, knocked both runners home with a double. 3-3. Third baseman-manager Patsy Tebeau followed, doubling in Virtue. Chief Zimmer partly redeemed himself with a hit to tally Tebeau. The teams headed to the seventh inning with Cleveland leading, 5-3.

But the rookie pitcher Fisher was obviously worn down. Nash hit a two-bagger. Tucker knocked him home with a single; then Ganzel doubled in Tucker. Carroll singled and Ganzel scored to regain the lead for the Beaneaters at 6-5. And they weren’t done. A fly ball to left field by Bennett was dropped by Jesse Burkett, scoring Carroll. Then Long’s single sent Bennett crossing the plate, which made it 8-5. Cleveland scored in bottom of the seventh to come within two runs but would score no more.

John McGraw, Wee Willie Keeler, and the famed Baltimore Orioles made so-called “scientific baseball” famous over the next few years. It was a combination of small ball as practiced by the Beaneaters, but also aggressive cheating. Boston was not above cheating either.

In the top of the eighth inning, Billy Nash doubled again. A bunt by Tommy Tucker moved him to third, but then Nash tried to score. Tucker threw his arms around pitcher Fisher as he covered first base on the bunt play, which prevented Fisher from throwing the ball to the catcher at home plate. It was the final run of the game.

As an interesting side note to the game, the Boston Globe reporter opened his game summary by stating that “on the merits of the game Cleveland ought to have won.” He noted the Spiders’ costly errors on Zimmer and Burkett but then added “[along] with some of the kind of umpiring that Hurst has done this summer.”9

“Hurst” was Timothy Carroll Hurst, the game’s umpire. Hurst was a bit pugnacious, for example hitting Kid Elberfeld in the jaw with his mask during a dispute and spitting on Eddie Collins, but generally he was just verbally combative.10 While the Globe reporter was sarcastic about Hurst’s umpiring skills, he concluded his game coverage by stating that Boston would have won the game anyway.

While John McGraw would have bragged about Tucker’s grabbing the first baseman, not explaining the cheating away, this third consecutive championship by the Beaneaters was indeed classic scientific baseball before Baltimore made scientific baseball famous.

Notes

1 “Chauncey Burr Fisher” Sports Legends, Madison County (Indiana) Historical Society website, mchs09.wordpress.com/sport-legends/

2 “Not This Time – Bostons Tangle Spiders in Their Own Web – The Errors Were Costly” Boston Post, September 21, 1893: 3.

3 “Pennant Comes to Boston; Cleveland Put Up Grand Ball but the Bostons ‘Got There,’” Boston Globe, September 21, 1893: 10.

4 New York Clipper, September 30, 1893: 485.

5 Charlie Bevis, “Timothy Murnane,” SABR Biography Project, sabr.org/bioproj/person/b2017f67.

6 T.H. Murnane, “Three-Time Winners, Graphic Story of How Boston’s Baseball Stars Climbed from the Ninth Place in the Great National Race to the Championship Pennant,” Boston Globe, September 24, 1893: 28; “It Is Ours – Proud Emblem to Wave Here Next Year – Boston Wins Base-Ball Pennant – Spiders Bite the Dust at Cleveland,” Boston Globe, September 21, 1893: 10.

7 “It Is Ours.”

8 “Not This Time.”

9 “Pennant Comes to Boston.”

10 Rick Huhn, “Tim Hurst’s Last Call,” in Morris Levin, ed., The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2013.)

Additional Stats

Boston Beaneaters 9

Cleveland Spiders 6

League Park

Cleveland, OH

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.