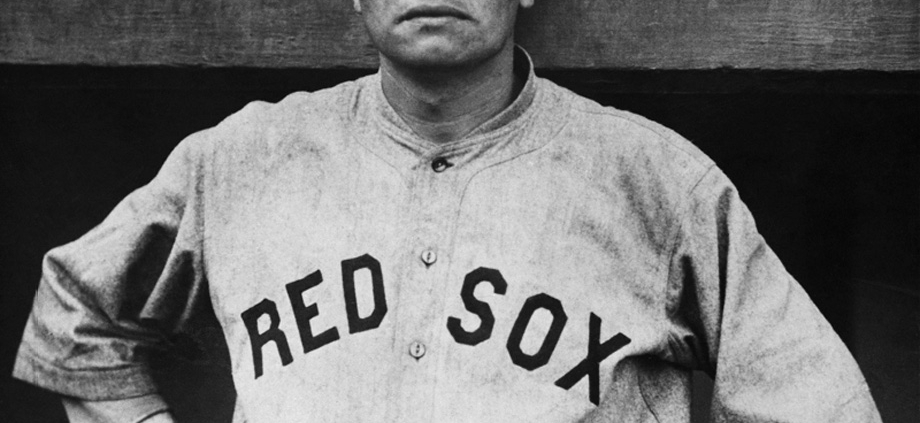

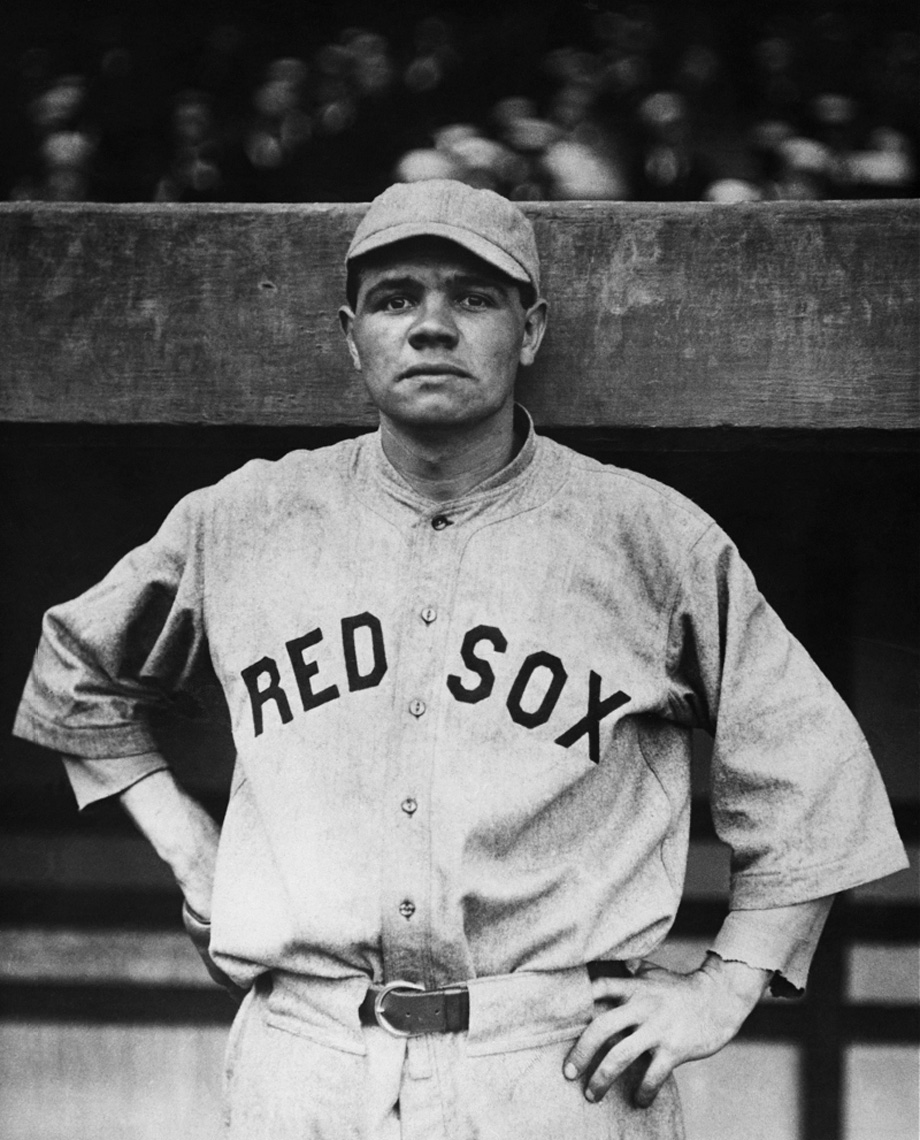

September 20, 1919: Babe Ruth ties single-season home run record with No. 27 in a walk-off

For 35 seasons, Ed Williamson of the Chicago Cubs held the major-league record for home runs in a season. In 1884, when pitchers tossed from a 4-foot-by-6-foot box, the front of which was located 50 feet from home plate, Williamson walloped 27 round-trippers, during a season in which he and three of his teammates, Fred Pfeffer (25), Abner Dalrymple (22), and Cap Anson (21), became the first big leaguers to hit at least 20 round-trippers in a season. Only four additional players clouted at least 20 in one season until 1919, when Babe Ruth emerged as the greatest slugger in the history of the sport.1

For 35 seasons, Ed Williamson of the Chicago Cubs held the major-league record for home runs in a season. In 1884, when pitchers tossed from a 4-foot-by-6-foot box, the front of which was located 50 feet from home plate, Williamson walloped 27 round-trippers, during a season in which he and three of his teammates, Fred Pfeffer (25), Abner Dalrymple (22), and Cap Anson (21), became the first big leaguers to hit at least 20 round-trippers in a season. Only four additional players clouted at least 20 in one season until 1919, when Babe Ruth emerged as the greatest slugger in the history of the sport.1

After winning the World Series in 1916 and 1918, the Boston Red Sox slogged through a disappointing campaign in 1919. Skipper Ed Barrow’s squad was in fifth-place (63-67), 22½ games behind their opponent, skipper Kid Gleason’s eventual pennant-winning Chicago White Sox (87-46), as they prepared for a Saturday afternoon twin bill and final home contests of the season.

Despite the ominous late morning skies, a crowd estimated by sportswriter Burt Whitman of the Boston Herald to be 30,000 strong packed Fenway Park for a special occasion, Babe Ruth Day.2 Fans were lined several deep in the outfield and cordoned off by rope while order was maintained by soldiers of the state guard. The celebration was sponsored by the Pere Marquette Council of the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic fraternal organization and mutual benefit society. Ruth himself was a member of the Council. An estimated 5,000 society members from throughout Massachusetts were on hand to cheer on their most famous representative.

Toeing the rubber for the Red Sox was none other than The Babe himself. The 24-year-old was once regarded as one of the best left-handed pitchers in baseball, winning 20 or more games in 1916 and 1917, leading the AL in ERA in 1916 (1.75), and owning a 3-0 record in the World Series, including a record 29⅔ consecutive scoreless innings (a record he held until Whitey Ford broke it in 1961). Despite his hurling successes, Ruth’s home-run prowess was transforming baseball. In 1918 he transitioned into a legitimate two-way player, making 19 starts on the mound and a combined 70 in the field (left field, center, and first base) and led the AL with 11 home runs. Ruth’s offensive juggernaut and assault on batting records in 1919 caught the attention of the nation, in need of distraction after the end of World War I. He was making his 15th start on the mound, though just third since the end of July, and sported a 9-5 slate (2.95 ERA). Few fans probably cared if Ruth’s curves were snapping; they paid admission to see him take his mighty swings. The Babe began the day leading the big leagues in home runs (26), RBIs (108), slugging (.650), and on-base-percentage (.457).

The Red Sox got on the board first, in the bottom of the first inning against White Sox starter Lefty Williams, who had emerged this season as one of the best southpaws in the league. He was 23-9 and was coming off a sparkling two-hit shutout nine days earlier against the Washington Senators in the nation’s capital. With two outs, the normally accurate Williams issued consecutive free passes to Braggo Roth and Ruth. Wally Shang followed with a hard grounder to shortstop Swede Risberg, who saved a run by knocking down the ball behind second, according to sportswriter I.E. Sanborn in the Chicago Tribune.3 With the bases jammed, Stuffy McInnis lined a single to left to drive in two runs. The Red Sox tallied their third run on an attempted double steal. When Chicago catcher Ray Schalk threw to Risberg to nab McInnis, Schang broke for home and scored while McInnis was caught in a rundown and eventually tagged out.

Despite the rough first, Williams pitched “air tight” ball, opined Sanborn, permitting just two baserunners, both singles, from the second inning through the eighth.4

Ruth sent the Fenway crowd in a frenzied round of applause by striking out three batters in the third while working around a walk and single. The White Sox broke through in the fourth, led by Buck Weaver’s leadoff double and Shoeless Joe Jackson’s run-scoring single. Happy Felsch singled, and Ruth’s errant throw to throw shortstop Everett Scott enabled both runners to move up a station. Chick Gandil’s deep fly brought home Jackson. “The Gleasons wrecked themselves by poor baserunning,” lamented Sanborn.5 With Ruth laboring, Felsch was caught stealing third. Risberg followed with a single, then was picked off first by Ruth to end the frame.

Ruth was greeted by what Whitman described as a “rude display of power” in the sixth.6 Weaver smashed a one-out double off the left-field fence and Shoeless Joe, en route to battling .351, beat out a single. Felsch’s two-bagger drove in Weaver to tie the game, 3-3, and force Ruth from the mound. In came reliever Allen Russell, a midseason acquisition from the New York Yankees, while Ruth moved to left field, replacing Bill Lamar. Baserunning blunders, coupled with some heads-up defensive plays, kept the score tied. Shortstop Scott fielded Gandil’s bounder up the middle and fired a strike to Schang to erase Jackson at the plate. With Risberg at bat, the White Sox’ double steal backfired when Schang’s rocket to third sacker Ossie Vitt easily beat a sliding Felsch for the final out.

Russell, a spitballing right-hander and the unsung hero of the game, tossed 3⅔ scoreless innings, walking one and fanning four. His strong performance set the stage for The Babe’s heroics.

In the bottom of the ninth, Ruth strolled to the plate after Roth had been called out on strikes for the first out. Williams was cautious and threw a pitch “high and fast and on the outside,” noted Whitman, adding that “they are afraid to pitch them close to Ruth, for fear that he will smack them over the right field bleacher.”7 It didn’t matter. Ruth connected, sending the orb “clean over the left field fence,” wrote Whitman, as the crowd burst into a euphoric yell.8 A svelte Ruth circled the bases for the winning-run, 4-3, in a fairy-tale setting.

“Never will we forget the setting of that 27th circuit crash by the Colossus,” gushed Whitman.9

Ruth’s round-tripper tied Williamson for the most in a single season, but the excitement was far from over. During the short intermission between games of the doubleheader, the festivities honoring Ruth took place at home plate. The local council of the Knight of Columbus presented Ruth with $600 in US Treasury bonds and a diamond-studded insignia, and also a box of cigars for his teammates. Ruth’s wife, Helen, was presented a decorated travel bag.

To cap off what proved to be his last home game as a member of the Red Sox, Ruth supplied more heroics in the second game. [Ruth was sold to the Yankees in the offseason]. With the score tied, 4-4, Ruth smashed a double to deep right-center field, clearing the row of fans in the outfield and bouncing off the bleacher wall, according to the Herald.10 Ruth thought it was a home run, as did other players, and a mini-protest erupted. Umpire Billy Evans finally ruled firmly that the ball was hit into the group of spectators and Ruth was permitted only a double. Ruth subsequently scored the winning run on Mike McNally’s grounder, which Risberg misplayed.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 Those four players were Sam Thompson (20 in 1889), Buck Freeman (25 in 1899), Frank Schulte (21 in 1911), and Gavvy Cravath (24 in 1915).

2 Burt Whitman, “Clouts of Mighty Babe Ruth Twice Tumble White Sox,” Boston Herald, September 21, 1919: Sport 1.

3 I.E. Sanborn, “Boston Impedes Sox Dash to Flag by Winning Pair,” Chicago Tribune, September 21, 1909: 17.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Whitman.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Boston Red Sox 4

Chicago White Sox 3

Game 1, DH

Fenway Park

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.