September 21, 1952: Braves bid adieu to Boston in home finale

The last home game of the 1952 season at Braves Field was played before 8,882 fans and nearly 32,000 empty seats on a Sunday afternoon in late September. Under the circumstances, this wasn’t much of a surprise.

The last home game of the 1952 season at Braves Field was played before 8,882 fans and nearly 32,000 empty seats on a Sunday afternoon in late September. Under the circumstances, this wasn’t much of a surprise.

There are plenty of numbers one can use to describe the ’52 Braves, most of them bad. Boston’s National League club finished in seventh place at 64-89, had no starting pitcher with a winning record, and batted .233 as a team. Although rookie third baseman Eddie Mathews hit an impressive 25 home runs, including three in one game, he had so few teammates getting on base ahead of him that he managed only 58 RBIs.1 Given such a substandard product to watch, just 281,278 fans ventured to Braves Field – the worst attendance in the major leagues and a cataclysmic decline of more than 80 percent from the 1,455,439 who had seen the 1948 pennant winners do battle four years before.2

Just how dismal were things at the Wigwam? The Braves drew 4,694 fans on Opening Day, and soon settled into a pattern in which the home crowds rarely went above that total. For the May 14 game against the Pittsburgh Pirates, the announced figure was 1,105, and Boston Globe photographer Paul J. Maguire took a photo that showed a vast expanse of the third-base pavilion in which one fan was seated all by himself in the last row. Sportswriters were so convinced that the 1,105 number was inflated that they decided to hand-count the fans themselves from the press box. They came up with less than 900, and the Globe claimed the official figure was later changed to 825 – the lowest in the 37-year history of Braves Field. 3

By the time the Braves faced off against the Brooklyn Dodgers in their home finale, which came in the midst of a 10-game losing streak, Boston had fallen 30 games behind the visitors, who were on the verge of clinching the National League pennant. Brooklyn’s All-Star lineup featuring future Hall of Famers Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, and Roy Campanella, and Cooperstown-worthy Gil Hodges. Boston manager Charlie Grimm countered with youngsters and old-timers whose best days were ahead of or behind them, including a pitcher in Jim Wilson who ended the season leading the league in earned runs allowed.4 Dodgers starter Joe Black, in contrast, was a favorite for both the National League Rookie of the Year and MVP awards with a 14-3 record, 15 saves, and a 2.03 ERA.5

It was a mismatch on paper, but most of the game played out as a very close affair. After the Dodgers took a 1-0 lead in the second inning on Campanella’s 22nd homer, the Braves went ahead on a wild play in the fourth. Johnny Logan opened the frame with a single, and then Mathews hit a shot that bounced over Hodges’ head at first base. Normally dead-on-accurate right fielder Carl Furillo charged the ball with his eyes set on getting Mathews at second, but his hurried throw went past the bag and deep into left field – allowing both Logan and Mathews to score.

The two unearned runs gave Boston a 2-1 edge, but Furillo atoned somewhat in the sixth when he doubled and came around to tie the game on two infield outs. According to Larry Claflin of the Boston Evening American, the crowd got ugly as the day wore on. Fans were particularly harsh on center fielder Sam Jethroe, the former NL Rookie of the Year now struggling with a batting average of .235 and a variety of fielding lapses, and Earl Torgeson, the once powerful and productive first baseman, who looked washed up at age 28 as a .227 singles hitter.6

Boos grew louder in the eighth, when the Dodgers got to Wilson and rookie reliever Virgil Jester for six runs – all of them scoring with two outs. There were four hits and three walks in all, including a two-run single from Black in support of his own cause and more atoning from Furillo in the form of a two-run double. Interestingly, Jester was lifted in the bottom of the frame in favor of pinch-hitter Warren Spahn, but Spahn would never go in to pitch. Manager Grimm, wanting to spare his ace left-hander the indignity of losing his 20th game of the year, was keeping Spahn and his 14-19 record away from the mound. Sheldon Jones came on instead to hurl an uneventful ninth for Boston, after which Black retired the Braves 1-2-3 to complete his three-hitter.

All told, Black had gotten the last 10 men in order and wound up not allowing an earned run. “Joe’s responsible for at least eight other wins for us that don’t show in his record,” Jackie Robinson (three hits in the contest) said after Black lowered his ERA to 1.90. “[NL umpire] Dusty Boggess says he’s the difference between us finishing first and third. He was great today and he’s been great all year. In my book he’s the most valuable player in the league.” Robinson wasn’t the only one excited, as he reported that he saw Black after the game “jumping up and down and saying, ‘I went nine! I went nine!’” He had gone eight innings on August 5, among his 54 relief assignments, but going the distance was a new experience for the rookie.7

Although the game did nothing for the Braves but bring them one day closer to the end of a horrid season, it was an important victory for Brooklyn. Coupled with a 6-2 loss by the New York Giants, it gave the Dodgers a six-game lead over New York with just six games to play. The worst Brooklyn could now do was tie for the pennant, and it would wind up clinching the flag in its next game with a September 23 win over the Philadelphia Phillies before the home folks at Ebbets Field.

It’s a good bet that the gamblers huddled in their usual spots in the Braves Field grandstands during the September 21 game did not wager much on the home team, but they would have given pretty big odds on one thing: Boston would still have two big-league clubs come the next spring. After all, the same 16 teams in the American and National leagues had played in the same 11 cities for half a century, and even though Braves majority owner Lou Perini had done some grumbling in the newspapers about how much money he was losing with the franchise, he had plenty of it in reserve, right?

“We are picking up the greatest check in baseball history this season,” Perini was quoted in the Boston Globe as saying after the home finale, estimating that his losses were currently reaching $30,000 per week. He said he intended to keep the team in his hometown for the time being, but added that “I’m not going to be stubborn about this thing. I don’t intend to spend 10 years here when people don’t want to see the Braves.”8 Eventual estimates were that the team lost Perini and his associates $580,000 for the year and more than $1.2 million from 1950 to 1952.9

“We are picking up the greatest check in baseball history this season,” Perini was quoted in the Boston Globe as saying after the home finale, estimating that his losses were currently reaching $30,000 per week. He said he intended to keep the team in his hometown for the time being, but added that “I’m not going to be stubborn about this thing. I don’t intend to spend 10 years here when people don’t want to see the Braves.”8 Eventual estimates were that the team lost Perini and his associates $580,000 for the year and more than $1.2 million from 1950 to 1952.9

According to Larry Claflin, Perini’s timeframe for patience was actually much smaller. “Lou Perini admitted today the Braves are in danger of losing their Boston franchise unless attendance improves in the next year or two,” Claflin wrote on September 22. Claflin said that a month earlier, during an exhibition game between the Braves and the Milwaukee Brewers, their top minor-league affiliate, in Milwaukee, Perini had suggested that the city was ready for a big-league team with construction of a 30,000-seat stadium (expandable to 80,000) already well under way. Perini did not go so far as to say that team could be the Braves, but he did, according to Claflin, predict that “a major league team would be playing in the new [Milwaukee] stadium soon.”10

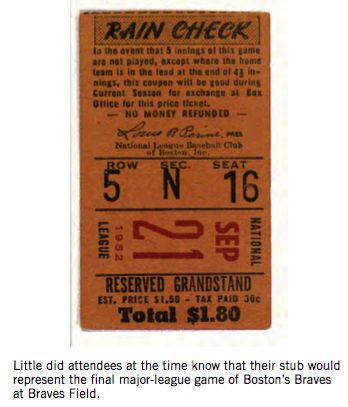

This might be the case, astute Braves fans surmised, but they knew that their team had several strong young players to build on – and would likely be a much improved club the next spring. Besides, said the armchair speculators, Perini was a Boston native with a big family that he surely didn’t want to uproot. The Hub had fielded an NL franchise since 1876, and it would do so again in 1953. As they quietly walked onto the “Braves Field” trolley cars that rolled down off Commonwealth Avenue and right into the ballpark, the disappointed crowd leaving the finale could at least be sure of that.

What they did not know, and what they may not have believed even if they could read between the lines of Larry Claflin and other columnists, was that outside forces would soon intervene to threaten the loyalty, patience, and tradition Perini was trying hard to uphold.11

This article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

Box scores for this game can be seen on baseball-reference.com, and retrosheet.org at:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN195209210.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1952/B09210BSN1952.htm

“Lou Perini Admits He Might Sell or Shift Braves,” Boston Evening American, September 22, 1952.

“281,000 Fans See Braves This Year,” Boston Evening American, September 22, 1952.

“Black Holds Braves to Three Hits, 8-2.” Boston Globe, September 22, 1952.

“Perini Sticks With Boston Despite ‘Greatest Loss in Baseball History,’” Boston Globe, September 22, 1952.

“Private Audience at Braves Field,” Boston Globe, March 17, 1953.

“Black Goes Route, Beats Braves for Leaders, 8-2,” Boston Herald, September 22, 1952.

“Braves Lose in Home Finale, 8-2,” Boston Post, September 22, 1952.

Kaese, Harold. The Boston Braves (New York: Putnam Press, 1948).

Notes

1 Future Hall of Famer Mathews garnered a meager one point in the Rookie of the Year balloting. Joe Black ran away with the award with 19 points. Black was a 28-year-old Negro League veteran and MLB “rookie,” who had performed for the Baltimore Elite Giants from 1943 to 1950, with time out for World War II military service.

2 The largest “crowd” the Braves drew at home all season was the 13,405 who saw Boston face these same Dodgers in a night game on July 5. Even that number was tainted, as the game marked the return of fan darling Tommy Holmes – who had been fired by the Braves as manager a month earlier and signed on as a spare outfielder for his hometown Brooklyn club. The sub-9,000 crowd at the finale was actually the second highest attendance mark of the year at the Wigwam – and the largest for a day game.

3 “Private Audience at Braves Field,” Boston Globe, March 17, 1953.

4 Wilson and Murry Dickson each allowed 110 runs in 1952.

5 Howell Stevens, “Braves Lose in Home Finale,” Boston Post, September 22, 1952. Black’s gaudy record to that point had been compiled exclusively in relief, but Dodgers manager Charley Dressen surprised Black when he arrived at the ballpark by telling him he was getting his first major-league start against the Braves. Although Dressen would not confirm it, it was assumed the move was a test to see if Black could handle a starting assignment in the World Series. It worked; his strong performance against Boston earned Black the opening-game start in the fall classic against the Yankees, and he would go the distance in a 4-2 win – although he lost two later starts in the series, including Game Seven.

6 Larry Claflin, “281,000 Fans See Braves This Year,” Boston Evening American, September 22, 1952.

7 Henry McKenna, “Black Goes Route, Beats Braves for Leaders, 8-2,” Boston Herald, September 22, 1952. Robinson’s MVP sentiments, however accurate, were not shared by the sportswriters. They voted the award to Hank Sauer of the Cubs in what is considered by baseball historian Bill James as one of the worst MVP selections in history.

8 Bob Holbrook, “Perini Sticks With Boston Despite ‘Greatest Loss in Baseball History,’” Boston Globe, September 22, 1952.

9 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves (New York: Putnam Press, 1948), 283.

10 Larry Claflin, “Lou Perini Admits He Might Sell or Shift Braves,” Boston Evening American, September 22, 1952.

11 Perini did go ahead and solicit season-ticket packages for the 1953 season in Boston and printed the tickets for the entire 1953 campaign. The team also issued a Boston Braves 1953 Press, Radio and Television Guide for use during spring training. Dual Red Sox-Braves pocket schedules (the usual format over the years) for 1953 had been printed for distribution and had to be hastily stamped on the Tribe side “Left Town.” Only 420 season tickets had been sold when the shift to Milwaukee was announced. On April Fool’s Day 1953, some 1,274,216 now useless tickets to games at the Wigwam were torched in a bonfire in the former major-league ballpark’s outfield.

While the rumors of a move abounded, Warren Spahn and his investors felt confident enough to spend the offseason preparing for the grand opening on Opening Day 1953 of Warren Spahn’s Restaurant, an ill-fated diner situated at 966 Commonwealth Ave., across from the Wigwam.

Boston Braves fans did get a chance to say goodbye to their beloved team when the Milwaukee Braves returned to Boston to play the Red Sox at Fenway Park as part of the pre-move commitment to the annual exhibition City Series, now awkwardly dubbed the “Cross Country Series.” The two games in Milwaukee were rained out. On April 11 the Red Sox triumphed, 4-1, and in a bone-chilling drizzle the following day, 7,873 saw the Braves emerge victorious by a similar score.

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Dodgers 8

Boston Braves 2

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.