September 29, 1871: Chicago beats Boston in last baseball game before the Great Fire

The Chicago Tribune described the Chicago White Stockings as “disaffected, demoralized and crippled” as the club prepared to clash with the Boston Red Stockings in a match of pennant contenders on September 29, 1871.1 With third baseman Ed Pinkham sick in bed and the club suffering from a host of other injuries, Chicago had not only lost its last two games to fall to 17-7, it had been drubbed 17-2 three days earlier by an amateur team, the Rockford Forest Citys.2 That loss heightened growing suspicions, arising from the recent announcement of the team’s roster for the 1872 season, that players who would not be returning to the club would have little incentive to help Chicago capture the championship.

Overcoming early-season injuries, Boston (18-9) was on a roll, having won 11 of its last 13 games, including the last six. The Tribune praised the team as “all that is hightoned and aristocratic in the professional fraternity.” In perfect health and without a “sore finger or lame leg” of the squad, the Red Stockings exuded confidence. “The red-legged gentry frisked and cavorted about the field before the game,” expecting to defeat Chicago as they had had on September 5, and to tie the season series at two games each.

A warm, sunny Midwestern day attracted at least 7,000 spectators to Chicago’s Lake Front Park (also called colloquially White Stockings Park) to take in an afternoon of baseball. “The White Stockings,” opined the Tribune, “undoubtedly occupied a larger share of the public attention than any other private citizens in the city.” After Chicago’s player-manager Jimmy Wood lost the customary coin toss to determine which team would bat first, umpire Harry McLean of the Washington Olympics called the game to order at 3:05.

Batting first, the Whites took a 1-0 lead in the first inning when striker Fred Treacey reached first on third baseman’s Harry Schafer’s error, stole second, and scored on another error by Schafer. In the second inning Charlie Hodes scored on Schafer’s third error to give Chicago a 2-0 lead. The Reds’ Al Spalding led off the second by walking, stealing second “by proxy in the person of the fleet-footed [Ross] Barnes,” and tallying the visitors’ first run. In the fourth inning Schafer redeemed himself by knocking in Cal McVey, who had led off with a walk, to tie the game.

Schafer, who was Boston’s starting third sacker for all five years in the National Association (1871-1875), was having a bad day, and was charged with seven of the team’s 11 errors.3 In those days of playing without a glove, Schafer muffed two more grounders in the fifth inning. Those miscues, coupled with Spalding’s wild pitch and McVey’s wild throw, led to two more Chicago runs. But Boston, whose average of 12.9 runs per game and .310 team batting average trailed only the eventual champion Philadelphia Athletics, stormed back. George Wright (whom the Tribune described as Boston’s “mainstay and chief reliance”), Ross Barnes, and McVey tallied safe hits leading to two runs, the first of which was the team’s only earned run of the game, and tied the game, 4-4.

Catching for Chicago was Marshall King, who had not played in a game for the White Stockings since August 16 while recovering from a broken finger. He “swore to stop every ball that [George] Zettlein pitched – if not with his hands, then with his head,” wrote the Tribune excitedly. However, in the fifth inning King suffered a “peculiarly painful and enervating injury” that forced him to change positions with Hodes (the regular catcher) in the middle of the following inning. One can only imagine what kind what injury befell the 21-year-old.

The sixth inning was the “turning point of the game,” opined the Tribune. Tom Foley, a much-maligned outfielder, led off with a single and scored on Hodes’ RBI single to left. The bases were loaded after Zettlein reached on Barnes’s muff and Bub McAtee, once described as a “player of coolness and judgment good under the most trying and exciting circumstances,” singled.4 Wood (whose .378 batting average paced the club in ’71) “dashed at a hip high ball,” belting it to left field and clearing the bases for an 8-4 Chicago lead. A “storm of cheers,” wrote the Tribune, “lasted for nearly five minutes.”

Boston, which the Tribune reported was often disdainfully termed the “plug bat nine” by some pitchers in the league, cut the deficit to two by scoring two unearned runs in the sixth. Noteworthy was the first of two Chicago double plays. After Harry Wright singled, his brother George hit a grounder to second baseman Jimmy Wood. Inexplicably, Harry raced back to first. Wood threw to first sacker McAtee to nab George; McAtee then fired back to Wood, who erased Harry, caught between the bases. The Whites turned their second double play of the game (they had 16 the entire season) the following inning when left fielder Treacey made a “brilliant” running catch of Dave Birdsall’s smash “just off the ground” and then doubled McVey (running for George Wright) off first.

Described as a “state of things too critical to be comfortable,” Chicago tacked on an insurance run in the seventh when Foley scored after two more errors by Schafer and a hit by Zettlein. In the ninth inning Treacey smashed a “beauty over [the fence] into Michigan Avenue”; however, according to Captain Jimmy Wood’s rules regarding balls over the fence, he was granted only first base. Treacey subsequently scored on a passed ball to give the Whites what appeared to be an insurmountable 10-6 lead.

According to the Tribune, the Red Stockings mounted a “savage and determined” comeback in the bottom of the ninth. Charlie Gould doubled to drive in Spalding and subsequently scored on a wild throw to second on a double steal to make the game 10-8. With Schafer on third and George Wright on first with two outs, Ross Barnes (who batted .401 and led the NA with 66 runs in just 31 games) was in position to tie the game with a double. However, he hit a high fly that Wood caught on the run “between the in and out fields” to secure Chicago’s exciting victory.

Chicago’s “nine ball players never worked harder, or more harmoniously, to win a doubtful and difficult contest,” wrote the Tribune, suggesting that all of the pregame concerns about the players and team were for naught. “They demonstrated that they are men of pride and principle.”

The Tribune noted many inconsistent calls by the umpire. For example, Treacey struck out in the sixth on a ball that was “positively over” the batter’s head; at other times, the paper reported incredulously of consecutive balls and strikes. In defense of the umpire, who admitted that he got “all mixed up,” the daily castigated spectators whose “jeers and howls at decisions adverse to the White Stockings were a disgrace to Chicago.” Seeking to preserve both the gentlemanly aspect of the sport and the behavior of the spectators, the Tribune suggested that more police are needed at games to suppress such “ruffianly demonstrations.” In a dig at spectators in the City of Brotherly Love, the paper suggested that “Chicago cannot afford to acquire a Philadelphia reputation with reference to baseball crowds.”

With the victory, Chicago took the season series from Boston, appeared to be the front-runner to win the National Association championship, and set up an anticipated matchup with Philadelphia. However, the White Stockings had to wait for more than two years and seven months before they played another professional game in Chicago.

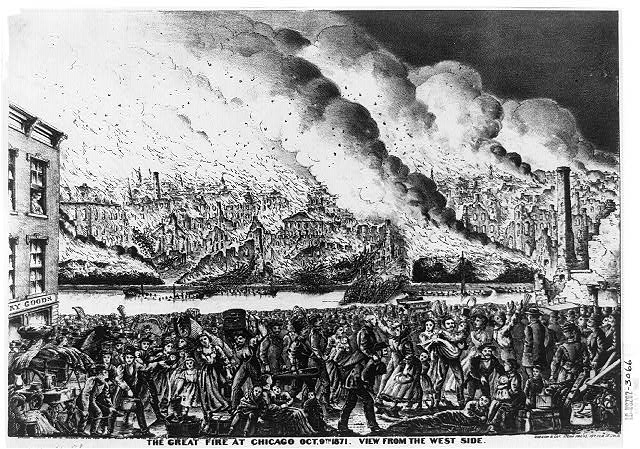

Disaster struck Chicago on Sunday night, October 8, when a massive fire erupted that destroyed about 3.3 square miles of the city, including much of the central business district (the Loop) and Lake Front Park, at the intersection of Michigan Avenue and Randolph Street (now Grant Park). The two-day fire killed an estimated 300 people and destroyed 17,000 structures.

The fire decimated the White Stockings. Though no players were injured, the team lost all of its equipment and uniforms. Most of the players were left homeless and in financial ruin. Undoubtedly more concerned about their friends and family and rebuilding their lives, they agreed to play the remaining games with borrowed gear on the road, splitting two games with the Troy Haymakers on October 21 and 23. Chicago concluded the season in an anticlimactic game on October 30 by playing Philadelphia at the Union Grounds in Brooklyn to determine the championship. On a neutral field, far from the fans of either city, the game drew only 500 fans who witnessed Athletics triumph, 4-1.

When Chicago defeated Philadelphia 4-0 at the newly rebuilt 23rd Street Grounds on May 13 to open the 1874 season and re-inaugurate professional baseball in the Windy City, only two players remained from the 1871 team: pitcher George Zettlein and outfielder Fred Treacey.

Notes

1 The play-by-play information for this game summary relies heavily on the very detailed game report from the Chicago Tribune. All of the quotations in this game summary are from the following edition unless otherwise noted: “Games and Pastimes. Fourth and Deciding Game Between the Whites and Red Stockings,” Chicago Tribune, September 30, 1871: 4.

2 “Games and Pastimes. The White Stockings at Rockford – How They Scored 2 to the Forest City’s 17,” Chicago Tribune, September 27, 1871: 4.

3 The Chicago Tribune reported that Schafer made two errors in the first, one in the second, two in the fifth, and two in the seventh.

4 “Games and Pastimes. Composition of Next Year’s White Stocking Nine,” Chicago Tribune, September 22, 1871: 1.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Stockings 10

Boston Red Stockings 8

Union Baseball Grounds

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.