September 4, 1888: The Little Steam Engine That Could: Pud Galvin’s 300th victory

The 21st-century baseball devotee has at his fingertips an abundance of statistical trivia the likes of which were undreamed of by his 19th-century counterpart. He is duly advised by the media when So-and-so has collected his 700th hit or Whatzizname has notched his fifth straight season of 20 stolen bases.

In the first decades of the National League, with Organized Baseball still relatively young, the concepts of “milestones” and “all-time records” had yet to coalesce in the minds of fans, media, and, no doubt, the players themselves.[fn]Bill Felber, correspondence with author, April 7, 2010.[/fn] Perhaps, too, there was a healthy disregard for becoming too obsessed with “the numbers.” The author of a May 12, 1878, Special Dispatch to the Chicago Daily Tribune, lamenting the intricacies of scoring fielder’s choices and players hit by batted balls, concluded that “It would be a splendid thing for the game if no record except that of runs were kept.”

In the first decades of the National League, with Organized Baseball still relatively young, the concepts of “milestones” and “all-time records” had yet to coalesce in the minds of fans, media, and, no doubt, the players themselves.[fn]Bill Felber, correspondence with author, April 7, 2010.[/fn] Perhaps, too, there was a healthy disregard for becoming too obsessed with “the numbers.” The author of a May 12, 1878, Special Dispatch to the Chicago Daily Tribune, lamenting the intricacies of scoring fielder’s choices and players hit by batted balls, concluded that “It would be a splendid thing for the game if no record except that of runs were kept.”

There was a maddening inexactness in contemporary record-keeping anyway: three newspapers could offer three different strikeout or error totals—with no video evidence to certify accuracy. So diamond warriors of that bygone age went merrily along without knowing what fodder they had strewn for the stat-gorging generations to come.

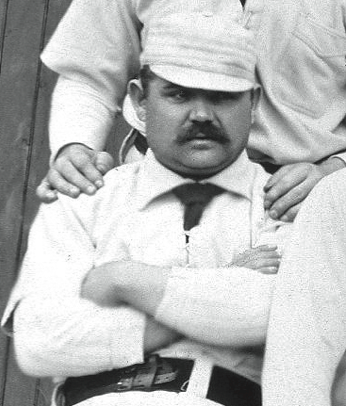

James Galvin, known to posterity as Pud (because he “made pudding of opposing batters”),[fn]Overfield, Joseph. “Jim Galvin,” Baseball’s First Stars (Cleveland, Ohio: SABR, 1996), p. 65.[/fn] hit the National Association in 1875, but kicked around for a few years before making his National League debut in 1879. Packing 190 pounds into a 5-foot-8 frame, he was sometimes called the Little Steam Engine, and he carved his Hall of Fame niche with consistency and endurance. The 1888 season was his 10th, excluding the one year in the National Association, and though still a valued hurler, he floundered through much of the season, thanks in considerable part to minimal run support. In mid-July his record stood at a miserable 5–17, but a couple of good streaks lifted him to 17–18 by the time his Pittsburgh club traveled to Indianapolis in the first week of September.

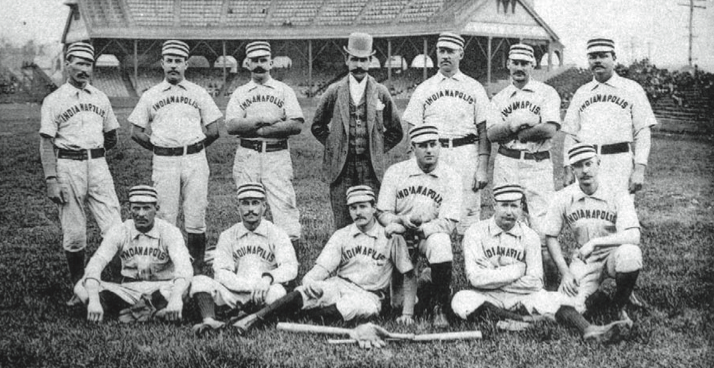

The five-game series promised little in the way of fireworks. Pittsburgh held a formidable 11-to-3 advantage in the season series against the Hoosiers. But the Alleghenies were long since out of pennant contention, struggling to pull themselves up to .500, and at best perhaps hoping for a fifth-place finish. Their hosts inhabited last place, having won only 37 of 103 games entering the series. Not exactly a marquee match-up.

On Monday, September 3, Galvin pitched ineffectively in the first game of a morning-afternoon twin-bill and went down to a 5-1 defeat. Pittsburgh rebounded to win the afternoon game, and The Little Steam Engine was due back in the box for game three the next day.

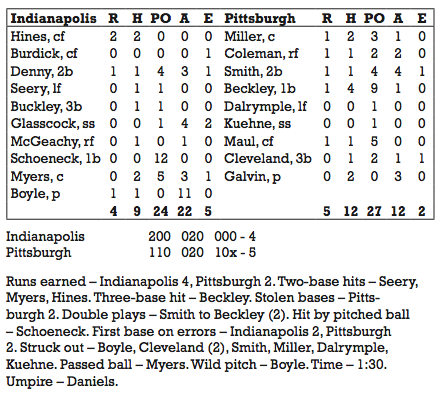

Seventh Street Park in Indianapolis seated a paltry crowd of 1,400 fans on Tuesday, September 4. For the second time in two days Galvin turned in a less-than-masterful effort, yielding nine hits and four earned runs, and winning only by the grace of three unearned runs scored by his team. In the seventh inning, rookie Indianapolis pitcher Bill Burdick, pressed into center-field duty when Paul Hines was injured, mishandled the only outfield chance of his major-league career, allowing the fifth and deciding Pittsburgh run to score. Sporting Life wrote that the home team was “demoralized in its field work, although it batted Galvin very hard.”[fn]Sporting Life, September 12, 1888, p. 3.[/fn] Pud managed but a solitary strikeout—the opposing pitcher, Handsome Henry Boyle. Rookie first baseman Jake Beckley, with 19 more seasons and an eventual place in the Hall of Fame ahead of him, went 4-for-4 in support of Galvin.

Seventh Street Park in Indianapolis seated a paltry crowd of 1,400 fans on Tuesday, September 4. For the second time in two days Galvin turned in a less-than-masterful effort, yielding nine hits and four earned runs, and winning only by the grace of three unearned runs scored by his team. In the seventh inning, rookie Indianapolis pitcher Bill Burdick, pressed into center-field duty when Paul Hines was injured, mishandled the only outfield chance of his major-league career, allowing the fifth and deciding Pittsburgh run to score. Sporting Life wrote that the home team was “demoralized in its field work, although it batted Galvin very hard.”[fn]Sporting Life, September 12, 1888, p. 3.[/fn] Pud managed but a solitary strikeout—the opposing pitcher, Handsome Henry Boyle. Rookie first baseman Jake Beckley, with 19 more seasons and an eventual place in the Hall of Fame ahead of him, went 4-for-4 in support of Galvin.

Seen merely in the context of the day, Galvin’s utterly unprepossessing pitching performance and, indeed, the game itself merit little attention. Yet on that date what would become the ultimate standard of pitching immortality was first reached—for the victory was the 300th of Pud Galvin’s career, a total no previous pitcher had achieved.

Since the National Association—in which Galvin won his first four victories—is not recognized by most authorities as a genuine major league, it should be mentioned that Galvin’s 300th victory in a league today recognized as “major” came about a month later, on October 5, when he triumphed on the road against Washington, 5–1. This time he let just one unearned run slip by, but again his teammates faltered at the bat and needed eight Washington errors and four unearned runs to post the victory.[fn]Sporting Life, October 10, 1888, p. 2.[/fn]

Galvin lasted four more seasons, retiring after the 1892 campaign with 365 victories to his credit, 361 of them in recognized major leagues. By that time Tim Keefe, Mickey Welch, Hoss Radbourn, and John Clarkson had also reached 300. But not until 1903 was Pud’s victory total surpassed, by Denton True Young, and only a handful have passed it since.

There was no mention of the milestone in the newspapers of the day. Reporters noted Pittsburgh’s brilliant fielding,[fn]Boston Daily Globe, September 5, 1888, p. 5.[/fn] a good throw from right field by Jack McGeachey,[fn]Chicago Daily Inter Ocean, September 5, 1888, p. 2.[/fn] and Beckley’s four hits[fn]New York Clipper, September 15, 1888, p. 432.[/fn]—but nothing about 300 wins. Who knows how long it took for someone—anyone—to take note? In 1906 a retrospective titled “Pitchers of the Past: Crack Twirlers of a Quarter Century Ago,” lauded Galvin as “a magician in the points” but made no mention of his 300 wins.[fn]Washington Post, February 11, 1906, p. S3.[/fn] The New York Times, proclaiming Lefty Grove “Twelfth To Gain No. 300” in 1941, appended a list of the elite dozen, which erroneously included non-300-game winner Tony Mullane and omitted Galvin.[fn]New York Times, July 26, 1941, p. 10.[/fn] The Hall of Fame plaque etched for his 1965 induction makes note of his two no-hitters and 649 complete games … but not that he was the first to break the 300 barrier.

Pud was not done with record-setting. Four seasons later, in his final major-league tour, he founded an even more exclusive club – only Cy Young has joined since then – when he became the first pitcher to lose 300 games.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Alleghenies 5

Indianapolis Hoosiers 4

Seventh Street Park

Indianapolis, IN

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.