September 5, 1918: Babe Ruth tosses shutout in Game 1 as patriotism prevails in World Series opener

With the war in Europe two months from the Allies’ victory, the 1918 World Series began. A meager yet patriotic crowd of 19,274 fans was on hand at Comiskey Park, “the smallest that has witnessed the diamond classic in many years.”1 The minds of the spectators were clearly on the overseas conflict, yet they came to see “an unusually brilliant exhibition of baseball.”2 The first game had originally been scheduled for September 4, but rain had caused a delay. Further, the venue was moved from the Cubs’ home ballpark, Weeghman Park (later renamed Wrigley Field), to Comiskey Park, “because it held more fans.”3 Many “believed that the Weeghman machine would win without allowing the American League club a single victory.”4

With the war in Europe two months from the Allies’ victory, the 1918 World Series began. A meager yet patriotic crowd of 19,274 fans was on hand at Comiskey Park, “the smallest that has witnessed the diamond classic in many years.”1 The minds of the spectators were clearly on the overseas conflict, yet they came to see “an unusually brilliant exhibition of baseball.”2 The first game had originally been scheduled for September 4, but rain had caused a delay. Further, the venue was moved from the Cubs’ home ballpark, Weeghman Park (later renamed Wrigley Field), to Comiskey Park, “because it held more fans.”3 Many “believed that the Weeghman machine would win without allowing the American League club a single victory.”4

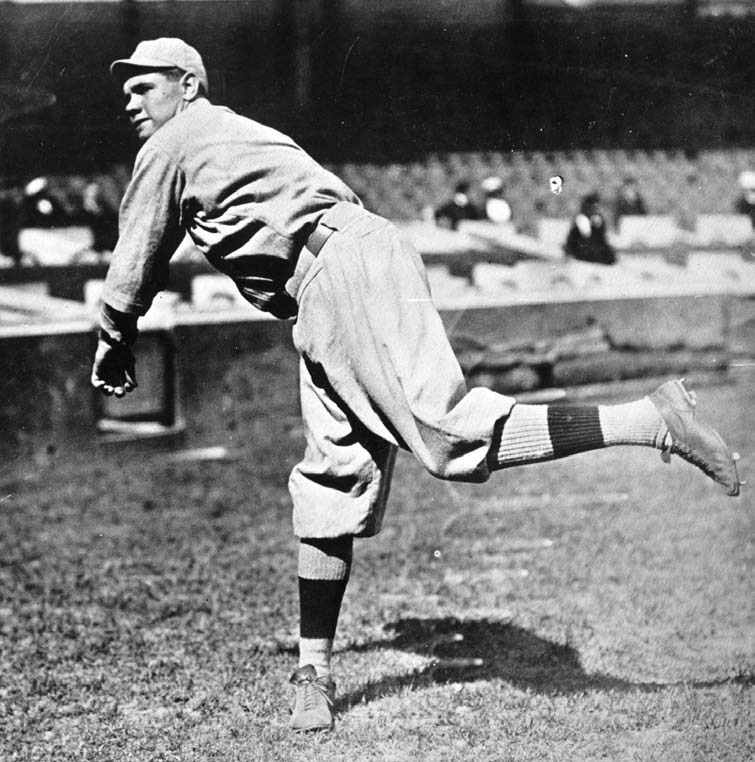

For the Red Sox, Joe Bush had been warming up to take the mound, but Boston skipper Ed Barrow surprised the Cubs as “the Baltimore mauler [Babe Ruth] was named for the task.”5 The Cubs countered with their ace, Hippo Vaughn. In a battle of southpaws, “these two giants fought it out all the way”6 in a classic pitchers’ duel.

Chicago threatened in the opening frame, “with victory within their grasp.”7 With two outs, Les Mann singled and motored to third when Dode Paskert hit a Texas leaguer to left field (Paskert advanced to second on the throw to third). Ruth then walked Fred Merkle to load the bases. With the game possibly depending “on his next offering, Ruth served up a low fastball to [Charlie] Pick, at the same time waving his outfielders back toward the bleachers.”8 Pick lifted the ball high into left, but George Whiteman made the catch to end the inning.

They may have taken Ruth’s pitching for granted, but the Cubs feared Ruth’s bat. When he hit the first ball in batting practice “into the right field bleachers, the crowd roared with appreciation.”9 And as the Babe strode to the plate in the top of the third inning, “Max Flack simply turned about and marched about forty paces toward the right wall,”10 while the crowd cheered, expecting some action. Ruth sent a deep line drive to right-center, and “the Cubs rooters groaned the moment their tympanums registered the sound of the bat and ball contact. It seemed a potential home run, but, as was the case throughout the afternoon with both sides, the high wind blowing directly against the batter, held back the swat and dropped it right into the mitt of the center fielder” Paskert, who had stumbled at first, recovered quickly, and ran down the ball for a long out. In his two other at-bats, Ruth fanned and “struck out in such a manner that the crowd tee-heed audibly.”11 Throughout the game, the Cubs “successfully stifled the perilous home-run bat of Ruth, but they overlooked the menace of his pitching arm.”12

Boston “did all of its stick execution in the first four innings, getting one hit in each of the first three, then grouping two for the winning tally in the fourth.”13 In the fourth, Vaughn allowed a leadoff walk to Dave Shean. Amos Strunk tried to bunt Shean to second but popped the ball up and Vaughn caught it. Whiteman did advance Shean to second, when he looped a single over short, bringing up Stuffy McInnis, “a notorious left-field hitter.”14 McInnis took Vaughn’s first offering for a ball, “but the second pitch came across to suit him and he dropped a rather indifferent rap into left field along the foul line. Proper preliminary coaching would have placed [Cubs left fielder] Mann directly in line for an easy catch on this ball and a resulting out, with no score.”15 Instead, this proved to be the game-winner. The New York Times reported that the “one lone run grew larger as the pitchers battled along, both displaying an impenetrable mysticism of curves.”16

The Cubs presented another opportunity in the sixth inning. With one down, “Paskert stung a hit to centre and Merkle slapped one to the same bailiwick, and Ruth was becoming plainly worried.”17 Boston’s Barrow waved to the bullpen and Bush started warming up again. Pick rolled a sacrifice down the first-base line and both runners advanced. When Ruth got Charlie Deal to fly out to left, the threat ended.

And then something happened during the seventh-inning stretch that was “far different from any incident that has ever occurred in the history of baseball. As the crowd … stood up to take their afternoon yawn,”18 a band from the Navy training station just north of Chicago began to play “The Star Spangled Banner.” This was the first time the song was played at a World Series game. “The yawns were checked and heads were bared as the ball players turned quickly and faced the music.”19 A few in the crowd began singing, then more joined in, until “a great volume of melody rolled across the field.”20 The crowd then “exploded into thunderous applause,”21 and the beginning of a new tradition was being witnessed. “Certainly the outpouring of sentiment, enthusiasm, and patriotism at the 1918 World Series went a long way to making the (song) the national anthem,” wrote John Thorn, the official historian of Major League Baseball.22 It would be another 13 years before President Herbert Hoover officially designated the song as America’s national anthem.23 From the New York Times: “If the greatest reason for playing this world’s series this year was to give the boys overseas something to talk about besides war, this game today will serve the purpose.”24

The Cubs made one last attempt in the bottom of the ninth. With two outs, Deal dragged a bunt down the third-base line and beat the throw from Thomas for a single. Bill McCabe came on as a pinch-runner. Then Bill Killefer “took one last grand slam at the ball and shot a high ballooner between right and centre fields,” but Hooper raced to the ball for the final out of the game. The Red Sox, behind Ruth’s pitching, had won, 1-0.

Several accounts of the game mentioned how few occasions there were for the fans to cheer. The Chicago Tribune commented, “From the ball player’s standpoint it was a great game, because of its proximity to perfection. From the rooter’s view point it was tame and monotonous because there were so few tense moments.”25 Further, “[T]he crowd present sat through the entire game, all primed to burst forth when the proper time came. But it never came, because Ruth never allowed an attack to go far enough to do damage.”26 Ruth allowed six hits and one walk in the win, striking out four. Vaughn yielded only five hits, all singles. He struck out six and walked three. Neither team made an error, and perhaps the difference came down to the Red Sox getting one hit with men in scoring position (1-for-7) while the Cubs were 0-for-5.

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Red Sox Beat Cubs in Initial Battle of World’s Series,” New York Times, September 6, 1918: 14.

2 Ibid.

3 Don Babwin (Associated Press), “1918 World Series Key in US Love Affair with National Anthem,” found online at https://bostonglobe.com/sports/redsox/2017/07/03/world-series-key-love-affair-with-national-anthem/J4XmvKVNXp69P4EQEU8piK/story.html. Accessed September 2017. Weeghman Park was the home of the Federal League’s Chicago Whales in 1914 and Chicago Chi-Feds in 1915. The Cubs started playing there in 1916 and have stayed. The name was changed to Cubs Park in 1920 and then to Wrigley Field in 1926.

4 John E. Wray, “Vaughn’s Defeat in World Series Opener Puts Bruins on Defensive in Pitching,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 6, 1918: 20.

5 New York Times.

6 “Sox Take First Game at Chicago,” Burlington (Vermont) Free Press, September 6, 1918: 1.

7 New York Times.

8 Burlington Free Press.

9 Edward F. Martin, “McInnis’ Smash Beats Cubs, 1-0,” Boston Globe, September 6, 1918: 4.

10 James Crusinberry, “All Primed to Yell, But Precise Hurling Gives Fan No Chance,” Chicago Tribune, September 6, 1918: 9.

11 Wray.

12 New York Times.

13 I.E. Sanborn, “Red Sox Grab First World’s Series Battle From Cubs, 1-0,” Chicago Tribune, September 6, 1918: 9.

14 “Crowd Present Seemed to Take Little Interest in Work of Rival Athletes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 6, 1918: 20.

15 Ibid.

16 New York Times.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Babwin.

23 Ibid.

24 New York Times.

25 Sanborn.

26 Crusinberry.

Additional Stats

Boston Red Sox 1

Chicago Cubs 0

Game 1, WS

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.