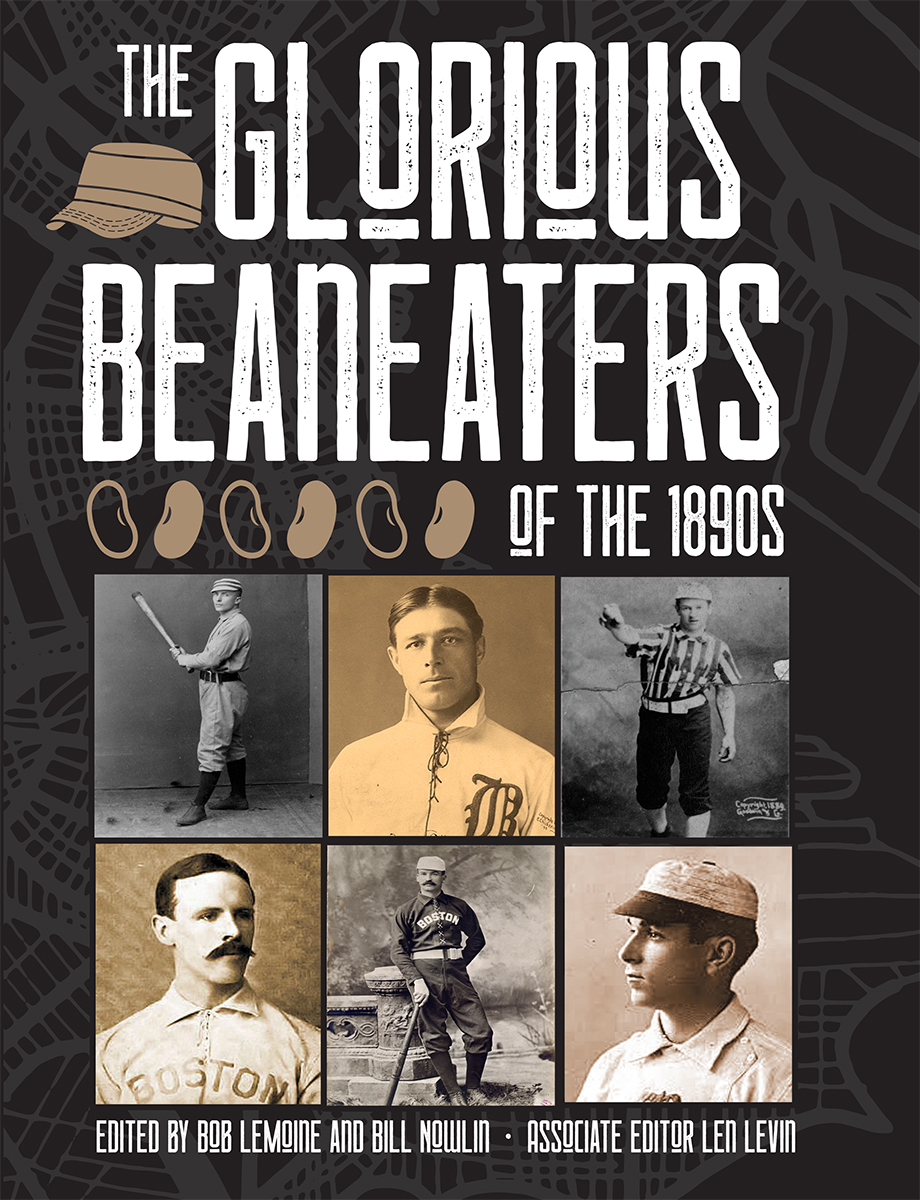

1893 Boston Beaneaters: 35-5 Summer Stretch Garners Third Straight Flag

This article was written by Dixie Tourangeau

This article was published in 1890s Boston Beaneaters essays

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness …”

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness …”

Novelist supreme Charles John Dickens was not a sportswriter and died (1870) 23 years before the 1893 Beaneaters season began, but the opening lines of his 1849 famed epic, A Tale of Two Cities, are perfect to describe the situation base ball found itself in by May 1893. Former player and Philadelphia sporting-goods entrepreneur A.J. Reach’s Official Base Ball Guide was on the stands by late March and told of how 1892 had been a disappointment to fans, players, and owners, but that 1893 would likely be better. There would be no competitors to the 12-team National League and the NL schedule was cut back to 132 games from 154. Opening days were in late April, the pitcher’s mound was moved back essentially 5 or 10 feet to facilitate more offense, owners had colluded and cut the largest player salaries (abhorrent to them and investors), and, finally, the split-season champion gimmick of 1892 was abolished. Because of these changes, there was springtime hope.1

Outside of baseball circles appeared the daily newspaper promotional reminders of mankind’s self-backslap of great achievements, in the form of the wondrous Chicago Columbian Exposition, the World’s Fair, within the spectacular 640-acre “White City,” a nineteenth-century Disneyland, which included the first (specially constructed) Ferris wheel as one of many attractions. Baseball would open on April 27, and the fair would commence entertaining the world on May 1. Unfortunately, few saw the national doom of May 4 on the horizon. On that day the National Cordage Company, based in New Jersey but with tentacles all over the East Coast, went into receivership as it neared bankruptcy. NCC manufactured rope and had tried to corner the hemp market.2 Overspending, wild speculation, and other reckless misdeeds by out-of-control businessmen combined to ignite the Panic of 1893, much larger in scope than the disastrous Panic of 1873.

The NCC fiasco followed the “red flag” bankruptcy of the Pennsylvania and Reading Railroad (February 20) due to much the same policies. Even the nation’s gold reserves almost disappeared because of bank runs caused by these developments. The economic catastrophe brought about became national as eventually 500 banks closed, 15,000 businesses collapsed, and unemployment soared to 20 percent by the summer. Within a week’s time, what should have been a pleasant start to the baseball campaign instead found the sport merely hoping to survive a huge problem it had no part in creating. Hindsight analysis of the Panic explains that it took nearly four years for things to crawl back to normal thanks in part to clever financier J.P. Morgan, who loaned the government millions to help restore order. The daily life atmosphere was treacherous, but it didn’t stop the World’s Fair crowds or enthusiasm for baseball.

Reach’s Guide had interesting news specifically for Boston’s fan base. “The great slump in base ball interest in Boston has puzzled students of the game everywhere. Up to 1890 Boston bore the deserved reputation of being the best base ball city in the country. No other city could make a pretense of disputing that claim with her. Last year (1892) with a winning team, the club could scarcely draw patronage to pay expenses. This year, it is expected, will see Boston return to the old crowds.”3 The Guide’s attendance stats showed that the South End Grounds drew just under 124,000 fans, placing ninth in the 12-team League (total draw was 1.67 million).

In October 1892 the game had a lucrative “World’s Championship Series” between Boston and Cleveland. It drew more than 20,000 in Cleveland’s three games and almost 12,000 in Boston for three more. The Spiders and Beaneaters played a 0-0 tie in the first game and then Boston won the next five, making a joke of the best-of-nine event. Even winning the championship at home didn’t bring out as many Boston fans as expected. The Beaneaters had now won two consecutive pennants and looked to equal the Chicago White Stockings of 1880-81-82 as three-time NL champs. Only its ancestral National Association Red Stockings of 1872-73-74-75 had won four straight along with the American Association (“Beer and Whiskey League”) St. Louis Browns of the mid-1880s.

Arthur Soden’s Beaneaters were a solid bunch and were kept hustling under the watchful eye of manager Frank Selee,then in his fourth season. The only changes made from 1892 were the release of aging stars, now deadweights, John Clarkson (p), Joe Quinn (2b), Mike King Kelly (c), and slugger Harry Stovey (of). Their slots were filled by younger teammates. Utilityman Bobby Lowe settled in at second base and Charlie Bennett and Charlie Ganzel formed the best catching tandem in the game. Cliff Carroll (of) was obtained from St. Louis and pitcher Hank Gastright arrived from Pittsburgh in July to round out the defending champions’ roster. The pitching core of Charlie “Kid” Nichols, “Happy Jack” Stivetts, Harry Staley, and Gastright threw all but 36 innings for the year. With the expanded schedule in 1892, both Nichols and Stivetts had won 35 games. The infield of Billy Nash (3b), Herman Long (ss), Lowe, and Tommy Tucker (1b) was superb while flychasers Hugh Duffy and Tommy McCarthy could hit, run, and field with any opponent.

Starting sluggishly, the Beaneaters were 12-11 in late May but that changed during their decade-longest 34-game homestand (24-10), which included an eight-game winning streak. Later three nine-game streaks helped them into first place to stay by July 28. The “friendly and beautiful confines” of the South End Grounds were always helpful to the Beaneaters (49-15). Only Nichols, Stivetts, and Staley pitched in the first 58 games, but in July Gastright was bought from Pittsburgh and went 12-4. His acquisition is notable because Pittsburgh finished second to Boston that year. It was the only season of the 1890s when the Pirates sniffed the pennant, yet they parted with a good pitcher. Pittsburgh finished second in pitching (4.08 ERA) to St. Louis (4.06) and third in batting average, .299 to Philadelphia’s .301. The Smoky City stars were Jake Beckley (.303), Denny Lyons (.306), Jack Glasscock (.341), Jake Stenzel (.362), Mike Smith (.346), George Van Haltren (.338), Connie Mack (.286), and pitcher Frank Killen (36-14). The Pirates beat Boston in the season’s series 6-4-1, with one postponed game not played, but they still finished five games out.

Despite being fifth in both ERA (4.43) and batting average (.290), the Beaneaters raised the pennant. They were second in runs, 1,008, to Philly’s 1,011 (played two more games). Boston finished 30-6 against Baltimore, St. Louis, and Louisville to gain their edge. Leading the club were Duffy (.363, fourth) and McCarthy (.346), while reserve catcher Bill Merritt hit .348 in 39 games. Long topped the circuit in runs scored (149), with Duffy close behind with 147. Billy Nash knocked home 123 mates (NL fourth). Lowe scored 130 runs and was tied for third in home runs with 14 to Ed Delahanty’s 19, two guys who were later etched together forever in the record books. Nichols finished 34-14, second in wins to Pirate Killen (36) and tied with Cy Young of Cleveland. Head to head, Kid and Killen split two games in September. Staley surrendered the most home runs in the League, 22, of Boston’s 66 total, topping the circuit. Offensively, Beaneater bats whacked 65 round-trippers, second to Philadelphia’s 80.

The most noteworthy personal mark of the Beaneaters season belongs to veteran Staley (18-10) because it still lingers, more than 125 years later. On June 1 at the South End Grounds vs. Louisville’s Hal Rhines, Harry belted two of his seven career home runs in a 15-4 win, plating nine runs in the process. It remains the Boston-Milwaukee-Atlanta franchise RBI record. It was equaled by Atlanta pitcher Tony Cloninger (two slams) on July 3, 1966. Stivetts (20-12) had the honor of tossing the only shutout at the South End Grounds all season when he blanked Chicago, 7-0, on August 31. On the opposite side of things, Cincinnati hurler Elton “Icebox” Chamberlain no-hit the champs on September 23 in Cincy, 6-0, in seven innings before the game was called due to darkness.

Of the players who made their first appearance in that NL season, the best careers belonged to Jimmy Bannon (he joined the Beaneaters in 1894), Bill Lange, Bill “Boileryard” Clarke, Heinie Reitz, George “Candy” LaChance (of the 1902-05 AL Bostons), and George “Tuck” Turner. Ending their careers were Clarkson, Quinn, King Kelly, Cliff Carroll (pickup who hit .224), Parisian Bob Caruthers, Smiling Tim Keefe (342 wins), four-time home-run champ Stovey, Sam Wise of the 1880s Bostons, Ed “Cannonball” Crane, and Boston catcher Charlie Bennett, who lost parts of both legs in a train accident in January 1894. He is often cited as the best catcher of the nineteenth century.

Among those notables who passed away were 1870s batting star Lipman Pike (.322), one of the first players paid for his talents; Elmer Sy Sutcliffe (.288), William Darby O’Brien (.282), John J. Fox (13-28), and Clarence G. Dow, 2-for-6 for the Boston Unions in September 1884. At his death the Boston Globe, Boston Post, and Sporting Life claimed Dow was thought of as the most reliable baseball statistician in the country.

In Reach’s 10-cent, 150-page publication for 1894, the 1893 campaign was declared a financial success despite the economic woes of the country. Attendance swelled and helped pay off a huge debt the League had incurred a few years before. Reach thought the reason the number of .300 hitters grew from a dozen in 1892 to more than 60 in 1893 was in great part the mound distance change. He claimed, “The Public interest in the game was thereby most certainly stimulated. The more uncertain quantity in games under the increased batting gave fascination to the sport and the crowds which filled the grounds of the various clubs attested to the popularity of the new rule and its workings.”4 According to Baseball-Reference.com, 193,000 saw games at the South End Grounds, ranking seventh of the 12 teams.

RICHARD “DIXIE” TOURANGEAU is a retired (2012) National Park Service ranger who has lived in his Boston triple-decker since 1974. It is one mile from the Beaneaters South End Grounds home, now part of his Northeastern University alma mater’s campus. He joined SABR in 1980 after being recruited by head Hall of Fame librarian Cliff Kachline. That same year he edited, then authored the Play Ball!! baseball calendar for Tide-Mark Press, of West Hartford, Connecticut. That research/writing task lasted 25 years through 2005’s issue. Just before this century began, Dixie decided it was time know “a little bit more” about 19th century base ball and took the plunge. Still immersed, he is trying to get a commemorative location sign for the iconic South End ballyard and a bronze plaque in Cooperstown for shortstop Herman Long. He roots mostly for the Rockies and Astros while petting four kitties. After 30 seasons, he gave up his Red Sox season tickets after 2017. As a volunteer guide, he gives tours on the museum ship, USS Cassin Young (DD793), at the old Charlestown Navy Yard, now Boston National Historical Park.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Refrence.com, and the following:

Appleton’s Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events for the Year (annual 1893-1897). (New York: D. Appleton & Company, annuals 1893-1897).

Stevens, Albert Clark. “An Analysis of the Phenomena of the Panic in the United States in 1893,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 8 (January 1894): 117-48. (Oxford University Press). jstor.org/stable/1883708.

Notes

1 Before 1893 the pitcher’s “box” was a five-foot area beginning 50 feet from home plate. The back boundary line was therefore 55 feet away but the hurler had the right to move around in his box to deliver a pitch. For 1893, new Rule 5 decreed: The pitcher’s boundary should be marked by a white rubber plate, twelve inches long and four inches wide, so fixed in the ground as to be even with the surface, at the distance of sixty feet and six inches from the outer corner of the home plate, so that a line drawn from the center of Home Base to the center of Second Base will give six inches on either side.

2 “Cordage Trust Goes Under,” New York Times, Friday, May 5, 1893: 1.

3 Reach Official Base Ball Guide (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach Co., Philadelphia, 1893), 44-45.

4 Reach Official Base Ball Guide (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach Co., Philadelphia, 1894), 10.