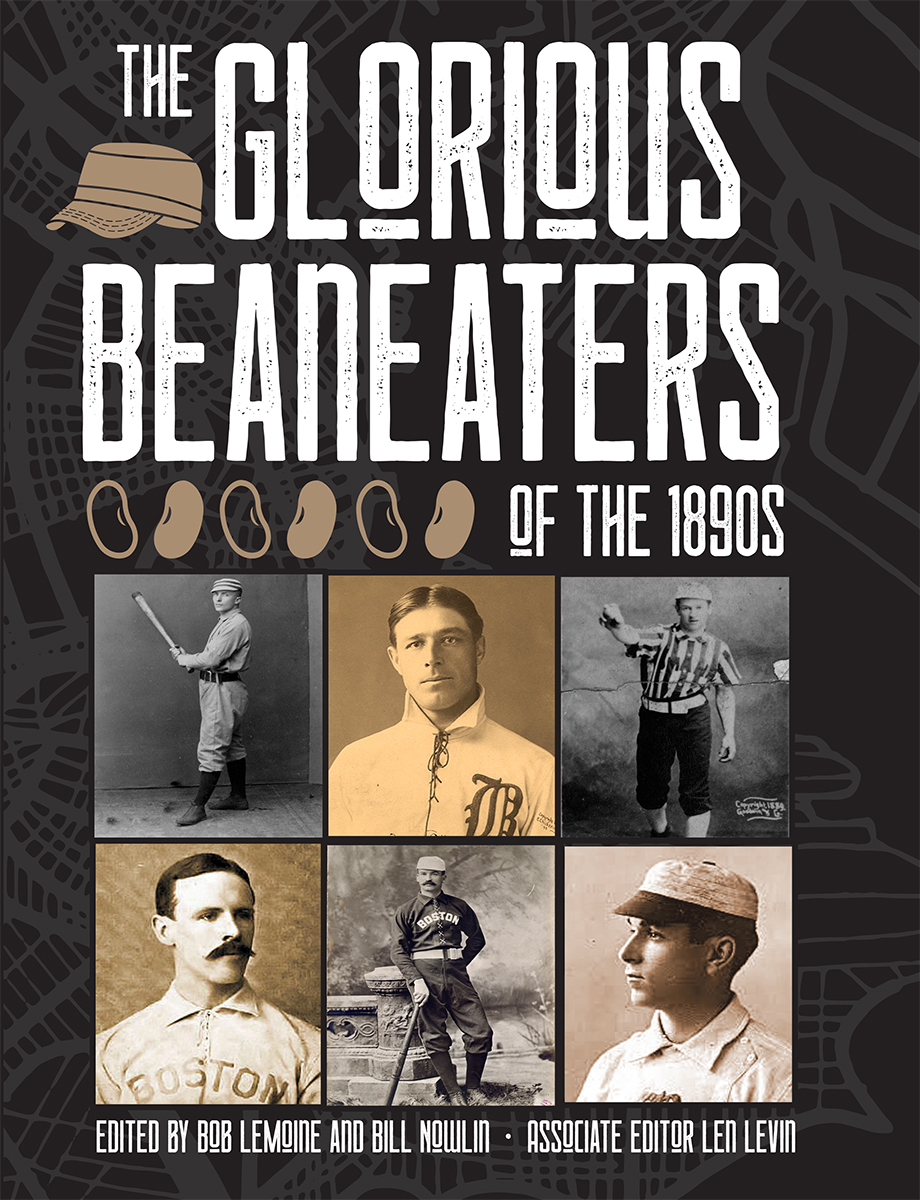

1898 Boston Beaneaters: A Very Long Season Ends with Another Flag

This article was written by Richard Riis

This article was published in 1890s Boston Beaneaters essays

Coming off their fourth National League pennant of the decade and seventh overall, the Boston Beaneaters were not considered a lock for the 1898 championship. Baseball touts and prognosticators were divided as to whether the club was up to a repeat, or if Baltimore, which had upset Boston in the Temple Cup, or New York, with a pitching staff perceived by many as the league’s best, might snatch the flag from manager Frank Selee’s men.

Coming off their fourth National League pennant of the decade and seventh overall, the Boston Beaneaters were not considered a lock for the 1898 championship. Baseball touts and prognosticators were divided as to whether the club was up to a repeat, or if Baltimore, which had upset Boston in the Temple Cup, or New York, with a pitching staff perceived by many as the league’s best, might snatch the flag from manager Frank Selee’s men.

Some of the uncertainty centered on Selee himself. The highly-regarded leader had given notice to the club in the offseason that he wished to be released from a verbal commitment to manage Boston again to assume ownership of a new Western League franchise in Omaha. Boston President Arthur Soden publicly dismissed questions about Selee with a statement to a reporter on January 22, saying that his manager “remarked that he would like nothing better than to have the Omaha franchise in the Western League, if he could get away from Boston, and his interviewer construed that to mean that he wanted to get away. He added, “Mr. Selee has said nothing to me about wanting a change. We are satisfied with him, and he seems satisfied here.”1

Nevertheless, the question of Selee’s status with the Beaneaters would continue to crop up throughout the season.

Other questions were fueled by the holdouts of two of Boston’s most gifted players, pitcher Charles “Kid” Nichols and third baseman Jimmy Collins. League owners voted in February to extend the season from 132 to 154 games with no discussion of additional compensation for players. A handful of players held out for more pay, including Nichols, the NL leader two years running with 30 and 31 wins, and Collins, while others revived talk of the organization of a players labor union.

“The shabby treatment accorded Nichols by the Boston Club, for whom he virtually won the championship last year, and other things, have spurred the players on to form an organization for their self-protection,” said the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “The demands of the players will be for increased pay, corresponding to the lengthened season, compensation for the weeks spent in spring training, and abolition of the current farming system.”2

Nichols arrived at training camp in Greensboro, North Carolina, without a contract, but Collins was conspicuously absent. Collins had emerged as a star in his third season in Boston, batting .346 with 132 RBIs, second most in the league, and 14 stolen bases. He excelled in the field as well, acquiring a reputation as the circuit’s premier third baseman as he led his peers in putouts and assists. Without Collins, the Beaneaters would find it difficult to repeat their 93-39 record of the previous season.

There were three changes on the Boston roster coming into training camp. Gone was catcher Charlie Ganzel, who, having lost his starting job in 1896 to Marty Bergen, was given his unconditional release in February. Added were two promising players, infielder Bill Keister and pitcher Vic Willis.

The left-handed-hitting Keister, 26, had played in 15 games at second and third for Baltimore in 1896 before hitting .334 in 1897 as the shortstop for Paterson of the Atlantic League. It was hoped Keister would provide the club with a solid utilityman to spell veterans Bobby Lowe and Herman Long at second and short. Neither Lowe nor Long seemed to need much rest in 1898 and Keister would see little action before being loaned to Rochester of the Eastern League for six weeks in June and July, then returned to Boston and released.

Willis, on the other hand, arrived on the club with considerable fanfare and an $1,800 contract,3 and was expected to join Nichols, Fred Klobedanz, and Ted Lewis in Frank Selee’s four-man pitching rotation. Willis, 22, was a tall right-hander acquired from Syracuse of the Eastern League for $1,000 and catcher Fred Lake after going 21-17 with a 1.16 ERA in 1897. Sportswriter H.G. Merrill, who covered the Eastern League for the Wilkes-Barre Record, wrote, “While I am one of the few writers who give the laugh to the chap who talks about strike-out records being a sure criterion of a pitcher’s ability, in the case of Willis, it is something worth considering, and is a criterion. … [W]ith the Boston team behind him, Willis ought to be a terror.”4

“My men are all little fellows,” explained Selee in justifying the club’s brief, two-week training camp, “and they do not need very much work to put them in good condition.”5 Breaking camp, the Beaneaters hit the road for exhibition games against Eastern League clubs in Lancaster, York, Reading, and Allentown, Pennsylvania, playing their way north to New York for the season opener vs. the Giants. Their outlook improved when Collins signed for the league’s unofficial maximum of $2,4006 and reported to the team on the road at the end of March.

Opening Day was scheduled for April 15. Selee pitted left-hander Klobedanz, 26-7 in 1897, against the Giants’ Ed Doheny. As both clubs marched ceremoniously onto the field behind a military band, a drizzling rain set in. With Boston ahead 3-2 in the third, the drizzle turned into a downpour, and the game was called.

The Beaneaters bested the Giants, 4-2, the next day in the official opener behind the pitching of Kid Nichols, in a game marred by confrontations on and off the field. “The enthusiasm was intense”7 as Boston rallied for two runs in the seventh inning to tie the game at 2-2. In the eighth, speedy Billy Hamilton reached on a groundball fumbled by third baseman Fred Hartman and advanced to second on a single by Fred Tenney. A throw by catcher Jack Warner to catch Hamilton off the bag went over shortstop George Davis’s head, and Hamilton took off for third. George Van Haltrenscooped up the ball in left field and threw to Hartman, who, according to some, tagged Hamilton a foot from the bag. Umpire Charles “Pop” Snyder, however, ruled Hamilton safe. The crowd howled their disapproval, and Giants player-manager Bill Joyce ran in from second base to argue. Second baseman Kid Gleason threw his glove down and kicked it, earning himself an ejection under the season’s tightened rules about on-field displays. A subsequent grounder to Gleason’s replacement, Charlie Gettig, was fired to the plate, but Hamilton, running at full bore, was called safe with the go-ahead run. When Boston followed up with another run, the crowd became unruly.

Approaching the grandstand to confront one egregiously abusive fan, umpire Snyder found himself pelted with a barrage of seat cushions and garbage, forcing Giants officials and police to take the field to quiet the crowd. After the game, fans clambered from the stands to confront Snyder, and the arbiter had to be escorted to the clubhouse by police. The Giants got their revenge against the “lucky” Bostons the following day, hitting Klobedanz freely for an 8-2 win.

The two clubs traveled to Boston for the opener at South End Grounds on April 19, where turnabout was again fair play, the Beaneaters bludgeoning the Giants for 18 hits and a 14-2 victory. Nichols gave up two runs on four hits in the first inning, then held the Giants hitless until he was relieved after seven innings by Lewis, who likewise kept the Giants off the basepaths. Lowe collected four hits and Nichols added a home run. After the game Nichols reportedly met with Arthur Soden and reached an undisclosed settlement on his contract.8

The the team left for an 11-game East Coast road trip. Vic Willis saw his first action on April 20, pitching three innings in relief of Jim Sullivan in an 18-3 drubbing at Union Park in Baltimore. Willis was “perceptibly nervous and unsteady,”9hitting the first two batters he faced before being tagged for eight runs on six hits, three walks, and a wild pitch.

Boston topped Baltimore 10-5 the following day, but on April 22, the Orioles again embarrassed the Beaneaters, and then some. Jay Hughes, a young hurler from California who impressed Orioles manager Ned Hanlon into signing him after he whitewashed Hanlon’s men on three hits in a postseason West Coast exhibition, tossed an 8-0 no-hitter against Boston in only the second start of his major-league career. (Cincinnati’s Ted Breitenstein pitched a no-hitter against Pittsburgh the same afternoon. This was the first time two no-hitters were thrown on the same day in the major leagues, a feat that wasn’t duplicated for almost a century”: The Oakland A’s Dave Stewart and the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Fernando Valenzuela turned the trick on June 29, 1990.)

Hughes’s gem was a particularly painful one for Long, who was plunked on the basepaths by a thrown ball and spiked in the foot and leg in a baserunning collision with Hughie Jennings and Dan McGann. Long nursed his wounds on the bench for the rest of the afternoon.

Making his first start on April 29, a settled-down Willis scattered 10 hits and struck out five in pitching all nine innings of an 11-4 victory at Washington. Klobedanz lost to the Senators the next day, and Boston finished April in a disappointing sixth place with six victories and five losses.

Returning home on May 5, the Beaneaters dropped three of four to the Giants, then righted themselves, taking three of four from the Orioles and sweeping three from Brooklyn. As the team departed Boston for their first Western trip of the season, they had moved into third place behind Cincinnati and Cleveland.

Kid Nichols took a 5-4 loss in the opening match of a three-game series in Cincinnati on May 19, but Vic Willis, despite obvious wildness in hitting two batters and walking eight, pitched well enough the next day to beat the Reds, 5-4, for his fifth win in as many starts. In the final matchup, on May 21, Lewis, saved by center fielder Billy Hamilton’s “wonderful catch”10 of a long drive by the Reds’ Jake Beckley with two men on, pulled out a 4-3 victory.

The press was impressed with Boston’s spirited play, even in pregame practice.

“What a snappy game of ball the champions put up at all stages! Even in their practice they are a revelation,” wrote the Cincinnati Enquirer. “Especially is this the case with Tenney, the collegiate first baseman. He never wearies, apparently, and is running and jumping about all the time. His practice shows up in the game, for circus stops and sensational pick-ups are ‘ready money’ for him. Herman Long is another of the Bostons who is doing ‘stunts’ half the time. The champs tackle their work with a vim and vigor that unquestionably presages the addition later on of another victory.”11

Boston’s hitting prowess drew sharp attention as well. “Billy Hamilton and Capt. Hugh Duffy came close to being the whole thing for Boston in the Cincinnati series,” said the Pittsburgh Press. “Their batting average off the Reds’ pitchers were .555 and .416 respectively. Herman Long rapped out .463.”12

“Take him day in and day out,” wrote another journalist about Billy Hamilton, “count what he does on the ‘inside’ as well as the outside, consider the clever manner in which he can wait out a pitcher, his wonderful batting eye, his skill in getting around the circuit, and I think I am justified in saying that if there is an individual entitled to be the best ball player in the world, it is Billy Hamilton.”13 Through May, Hamilton topped the league in hitting, with an average as high as .425.14

The Beaneaters experienced their most unusual loss of the season on May 28 in Louisville. Both teams had agreed to have the day’s game called at 5 P.M. to allow them to catch a train for the East. Trailing 7-5 after eight innings, Boston scored five runs with only one out in the ninth when umpire Hank O’Day called the game. To the Beaneaters’ disgust and the Colonels’ delight, the score reverted to the last completed inning, giving Louisville the victory.

From May 30 through June 1, the Beaneaters took four straight at home from Chicago to find themselves in second place, four games behind red-hot Cincinnati.

On June 7, Boston, 4½ games behind Cincinnati, hosted the Reds in the first of a four-game series. Three hits, including a home run by Hamilton, and effective pitching by Nichols gave Boston a 9-2 victory and, coupled with a Brooklyn win over Cleveland, moved the Beaneaters into a second-place tie with the Spiders.

The next day Willis, struggling with his control, walked eight but managed to beat the Reds, 8-1. Cleveland downed Brooklyn 8-2.

After Cincinnati tied the game of June 9 in the top of the ninth, Jack Stivetts, batting for Klobedanz in the bottom of the inning, connected for a solo home run to give Boston a 6-5 victory. It was his third pinch-hit home run and the last of his 35 homers in the major leagues.15

Boston failed to complete the sweep, though, falling on June 10 to the Reds, 4-3, on a home run by Dusty Miller, while the Spiders won their third straight to push the Beaneaters back into third place.

Back-to-back wins against the Phillies on June 12-13 put Boston back into a tie for second place. On June 14 Willis struck out 11, only to lose to Philadelphia 9-0.

Despite the absence of Hamilton and Long with minor injuries, Boston collected 17 hits in beating Philadelphia 12-6 on June 15 to take sole possession of second place, 2½ games behind Cincinnati. By June 20 Boston had cut Cincinnati’s lead to a single game; a week later, they were only a half-game out of first place. Boston’s hitting, while somewhat weaker than the previous season’s, still impressed, with Hamilton topping his teammates at .386, followed by Collins at .319, Jake Stahl and Bergen at .314, Tenney at .313, and Hugh Duffy at .299 through June 25.16

The Beaneaters had begun playing mediocre ball, though. From June 20 through July 2, they were 5-7. On July 1 Cincinnati began an eight-game winning streak that put them up five games on Boston.

On a sweltering day in Philadelphia, the Beaneaters failed to come up with as much as a hit on July 8 for the second time in the season, Red Donahue issued only two walks in taming Boston, 5-0. “[Donahue] gave the most brilliant exhibition of twisting the sphere that has been seen on the local grounds this season,” noted the Philadelphia Times. “Not a Champion got beyond second base during the entire nine innings, and not a single Champion got a safe hit during the entire nine innings.”17 Willis, on the other hand, was wild again, walking eight and hitting two batters.

Starting with a Fourth of July doubleheader sweep of the Giants at New York, Boston caught fire again, winning four straight, losing two, then winning 15 of 18. An equally torrid streak by Cincinnati, which won 18 of 24 with one tie over the same span, kept the Bostons from gaining much ground on the Reds.

The status of Selee’s job as manager was raised again in July, with considerable doubt raised by Selee himself. “I expect to own a club next year,” he told a reporter in Pittsburgh, adding that he’d remained with Boston this season only because he’d given his word to the owners.18

While still winning games, the Beaneaters were beginning to show some wear and tear. Hamilton and Stahl were both felled by serious knee injuries, and Tenney was laid low by a serious stomach ailment. With all three regulars expected to be out for a lengthy stretch and pitcher-outfielder Stivetts banged up with a split thumb, on July 25 the Beaneaters signed utilityman Jim “General” Stafford, recently released by Louisville, to play right field in place of Stahl. Backup receiver George Yeager assumed Tenney’s duties at first base.

On July 25, in a game at New York’s Polo Grounds, Orioles left fielder James “Ducky” Holmes struck out. On his way back to the bench, he responded to the heckling of fans by referring to Giants team owner Andrew Freedman with an anti-Semitic slur. Freedman, seated within earshot, demanded that Holmes be removed from the game. Orioles manager Ned Hanlon refused, whereupon Freedman ordered Giants skipper Bill Joyce to keep his players on the bench. The game was forfeited to Baltimore.

The incident left league officials in a quandary. Freedman demanded disciplinary action against Holmes, while Hanlon demanded punitive sanctions against Freedman for causing the game forfeiture and for withholding Baltimore’s share of the gate for the game. Trying to placate both sides, the NL Board of Discipline fined Freedman $1,000 and imposed a season-long suspension on Holmes. The Orioles were given until August 24 to comply with the ruling.

Deeming Holmes’s suspension illegal because it had been imposed without affording the player a hearing, NL players urged that it be lifted. The Beaneaters passed a collective resolution condemning Holmes’ suspension, calling the verdict “extremely erroneous and such arbitrary use of power extremely unjust,” and criticizing the autocratic and abrasive Freedman for manifesting “a spirit of impatience, intolerance, arrogance, and prejudice against players, a spirit inimical to the best interest of the game and the public.”19 The resolution was signed by all 15 Beaneaters and sent to newspapers and the Board of Directors of the National League. On August 25, with the support of nine of the league’s owners, the order of suspension against Holmes was lifted.

Of likely greater concern to Boston’s players was a growing problem with one of their own, Marty Bergen. Considered by many as the league’s most gifted backstop, Bergen had been regarded by his teammates as eccentric, but his disposition over the course of the season had taken a turn for the worse, bringing discord to the tight-knit club. “Backstop Marty Bergen,” wrote one journalist, “with all his talents as a catcher, is an odd specimen with a grievance continually concealed in his craw.”20

There was an incident between Bergen and Vic Willis in the dining room of a St. Louis hotel on July 28 that went unreported in the press until after the season. Willis, Bergen, and other players were kidding one another on the train from Brooklyn the previous night. Suddenly, Bergen grew morose and withdrawn. The next morning, as teammate Ted Lewis later recalled, “(Bergen) was talking in an apparently friendly way with Willis, who sat down in a chair next to him, but in an instant, however, he drew back his arm and struck Willis in the face.”21 Intervening Boston players led Willis from the room to avoid escalating the situation.

“Bergen, often surly, lets his temper get away with him,” observed one sportswriter, “and makes breaks for which there is no provocation.”22 Relations between Bergen and his teammates were seriously strained after the incident.

Despite the off-field distractions, Boston played at a .720 clip in July, winning 18 of 25, to remain in second place, 3½ games behind Cincinnati, and 2½ games ahead of Cleveland.

The Beaneaters beat St. Louis 4-3 in the first game of a doubleheader on August 1, then entered into a collective slump, losing five of six with one tie, scoring only one run in four of the six. In the 12-inning tie game, played in Louisville, Boston went into the ninth with a 1-0 lead, but a walk, stolen base, error, and a groundout produced the tying run and sent the game into extra innings. Nichols and Louisville’s Bill Magee both pitched all 12 innings, surrendering but six and seven hits, respectively.

Less than a month after Selee called him “one of the prettiest batters in the league” and “one of the best utility men in the business,”23 the Beaneaters made a deal with the Browns to swap Jack Stivetts for Kid Carsey, a washed-up pitcher already past his prime at 25, and cash. The trade, though, was made contingent on Stivetts’s consent to go to St. Louis, whereupon Stivetts declined, prompting Boston to send him home to think it over. For a while the deal hung in limbo, until Browns owner Chris von der Ahe came back on August 14 with a straight cash offer of $2,000, which Boston accepted.24 Stivetts refused to report to St. Louis and was sold by the Browns to Cleveland for the 1899 season.

Stivetts’s spot on the roster was filled with a catcher-outfielder signed from the semipro leagues of Worcester, Massachusetts. William “Kitty” Bransfield, 23, played in only five games before being released to Brockton of the Eastern League. He returned to the major leagues later and enjoyed a respectable career as a first baseman for the Pirates and Phillies.

Boston realized its longest winning streak of the season, 11 games, beginning with an 8-0 whitewash of the Reds at Cincinnati on August 9, and concluding with a 2-1 victory over the Reds at home on August 20. Behind superb pitching that surrendered only 23 runs in those 11 games, including shutouts by Nichols, Willis, and the tandem of Lewis and Charlie Hickman. Hickman and Jim Stafford enjoyed a stellar outing in Boston’s 10-0 rout of Chicago on August 18. Stafford, playing right field in place of an again-injured Stahl, collected four hits in four at-bats, including his only home run of the season. Hickman, sent in to give Lewis the rest of the afternoon off after the starter had given up but one hit in five innings, hurled four innings of one-hit ball and hit a double. (He eventually transitioned from pitching to playing first base and enjoyed some solid seasons with the Giants and future American League teams in Cleveland, Detroit, and Washington.)

With Boston in first by 3½ games, the Beaneaters drew their largest crowd of the season, 12,000, for an August 22 doubleheader against second-place Cincinnati. The crowd was so large that ropes were put around the field to keep them back, but several times they pushed their way onto the field of play and in the way of the fielders. A ground rule was established that a ball hit into the crowd was a double. Stahl sat out both games with a sore knee, and Tenney also withdrew, complaining of stiffness in his leg.

Nichols was ineffective in the opener, pitching only seven innings in a 7-2 loss. Controversy arose when in the third inning Heine Peitz opened for the Reds with a single, advanced to second on a passed ball, and, with one out, scored on a single by Mike Smith. Smith took second on the second out of the inning, and trotted home on a groundball by Bid McPhee to Collins, who threw to first for the third out. The Beaneaters had come in from when the field when umpire Tom Brown ruled that George Yeager had his foot off the bag when he caught the throw, McPhee was safe, and Smith’s run counted. The Beaneaters charged back onto the field to object, and Yeager wound up ejected, with Kitty Bransfield, making his major-league debut, replacing him at first for the remainder of the game.

The second game began with the understanding that the game would be called at 5:45 P.M. In the sixth inning, with Boston up, 5-3, McPhee homered, and singles by Jake Beckley and Charlie Irwin brought Dusty Miller to the plate. On Lewis’s first pitch, Miller hit a line drive to center field. Hamilton took off after the ball, racing toward the fence, when he hit the rope holding back the crowd and was flipped onto his back. While Hamilton lay dazed on the field, the umpire called a ground-rule double, and Beckley scored to tie the game. Hamilton was several minutes in recovering,25 and after the Reds were finally retired, Boston came to bat with only 10 minutes left.

If Boston was still at bat when the game was called at 5:45, the score would revert to that of the last completed inning, giving the Beaneaters the victory, but Yeager struck out, and after Long singled, Duffy and Collins each drove the ball deep to left field, only to have them hauled in by Mike Smith. The game was called, and a 5-5 tie entered into the books.

Fred Tenney, his leg still stiff, was left behind as Boston headed west on a road trip on August 24. With Tenney out, Boston won but three of 12 games, allowing Cincinnati to slip past Boston and back into the lead on September 1. A 6-6 tie with Cleveland on September 2, called after 10 innings because of darkness, found Boston looking distracted and listless. “The game should have been won by the Boston,” according to one account, “but poor running, weird fielding, and Lewis’ lack of control and speed all but lost it.”26 Club President Soden was disgusted. “The playing of the team the last two weeks is the worst it’s been in years,” he said.27

Bergen abruptly took unauthorized leave of the club for a trip to his home in North Brookfield, Massachusetts. With Bergen missing for two days (and subsequently fined), Yeager, who had been substituting for Tenney at first base, had to catch, and when Boston took the field against New York on September 3, Kid Nichols was at first. The Beaneaters beat the Giants, 6-5, with Nichols batting ninth behind pitcher Lewis. “Manager Selee was responsible for as poor a piece of judgment as ever befell the lot of a baseball manager,” wrote a baffled Boston sportswriter, Tim Murnane, a former major leaguer. “The idea of using a great pitcher at first base, taking chances of having him put out of the game for the rest of the season was enough to make the directors of the Boston club wonder if their manager was in his right mind when he made out the batting order.”28 For the next game, and every other until Tenney returned to the lineup, Hickman, a less valuable pitcher than Nichols, substituted at first base. The slow return of Tenney prompted Captain Duffy to gripe about contemporary players getting soft. Speaking to a reporter, he said, “There are too many doctors in the game now.”29

No sooner had Tenney returned to the lineup than Hamilton, batting .369, close behind the Orioles’ Willie Keeler atop the list of NL hitters, went down again with his nagging knee injury. Duffy was moved to center field and Stafford took over in left. As Cincinnati faded, Boston went on a nine-game winning streak beginning September 3.

Coming into the pennant stretch, newspapers once again reported that “Frank Selee, the highly successful and rightfully popular manager of the Boston team, will quit the city of beans and crooked streets at the end of the pennant season.”30This time Selee remained silent, even as many speculated that Hugh Duffy would succeed Selee.

Despite an exciting pennant race, attendance around the league was lagging, and Nick Young, president of the National League, said near season’s end that seven of the league’s 12 clubs – St. Louis, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Washington, New York, Brooklyn, and even perennial contender Baltimore – were losing money.31 Most, including Young, ascribed the decline in attendance to fans’ preoccupation with the Spanish-American War. On April 25 the United States had declared war on Spain after the explosion aboard the battleship Maine in Havana harbor on February 15, and war news dominated the newspapers and the national conversation. Perhaps that was the case when Boston reclaimed first place with a pair of Labor Day victories over Washington on September 5. In the morning game, Willis won 2-1 before 2,200 fans; in the afternoon, Nichols stopped the Senators 6-2 before 6,500. A year before, a Labor Day doubleheader in Boston had drawn 6,500 and 12,000.

The Orioles, still very much in the chase, reeled off 12 straight victories, cutting Boston’s lead to 2½ games on September 22, but fell back when Chicago snapped their winning streak. That same day, Willis beat Philadelphia, 2-1, with a double by Duffy winning the game in the ninth.

The Beaneaters drew within grasp of the pennant by taking a pair from Brooklyn on September 26 for their seventh and eighth wins in a row, while Washington was beating Baltimore. Selee then made a curious choice by starting Willis two games in a row. Willis beat Brooklyn, 3-1, on September 27, but was frequently in trouble. The next day Brooklyn battered Willis, Duffy was tossed from the game for arguing with the umpire, and Boston’s win streak was snapped at eight.

No matter. The Beaneaters toppled Philadelphia 11-10 on September 29 with a six-run rally in the ninth inning, highlighted by a three-run home run by Collins that tied the score, and Stahl’s sprint home after Lewis’s fly fell between three Phillies in left field.

On October 3, in what the Boston Globe called the “most curious game of the season,”32 the Beaneaters seemed to do everything within their power to hand the game to the visiting Orioles, making 10 errors in the first four innings, “misplays that brought tears of laughter to the Oriole players and long looks of disgust from manager Frank Selee.”33Four errors were made in the first inning, and four more in the third, as the Orioles took a 6-3 lead. Boston then batted around in the fourth, with two hits in the inning by Willis and a home run by Bergen netting six runs, to pull ahead, 9-6. The Orioles answered with four runs in the bottom of the inning to retake the lead, 10-9, before Boston plated three more runs in the fifth. Adding another run in the sixth, the Beaneaters pulled out an abbreviated 13-10 win when umpire John Gaffney ruled it too dark to continue play.

Having won four in a row, the Beaneaters ran the streak up to nine before dropping two of three to complete the schedule. When the season ended October 15, Boston’s record stood at 102-47, six games ahead of Baltimore and 11½ up on Cincinnati, in capturing the NL pennant for the second straight year.

Several Beaneaters enjoyed fine seasons. Hamilton finished second in the batting race at .369 and in stolen bases (54), and was first in on-base percentage (.480). Limited by his knee injuries to 110 games, he nevertheless scored 110 runs. Collins hit .328, led the NL in home runs with 15 and in total bases with 286, and was second in RBIs (111) and slugging percentage (.479). Tenney hit .328. Although Duffy’s batting average slumped from .340 to .298, he drove in 108 runs, fourth-best in the league. Among the league’s hurlers, Kid Nichols was the winningest pitcher for the third consecutive year with a 31-12 won-lost record, his third and last season with 30 or more victories. He was third in ERA (2.13) and fourth in strikeouts (138). Rookie Willis went 25-13 to launch a Hall of Fame career and finished third in the league with 160 strikeouts. Lewis, 26-8, topped NL hurlers with a .765 won-lost percentage. Klobedanz logged 19 wins against 10 losses. Willis, Collins, Duffy, Hamilton, and Nichols are in the Hall of Fame. Boston’s dynasty was coming to a close in 1898, but such stars made this team, in the words of historian David Nemec, “the greatest team of the 1890s.”34

On a more ominous note, there were reports that Marty Bergen, after an altercation on the bench in one of the season’s final games, had grabbed a bat and threatened to club a few of the Beaneaters. He didn’t, but Bergen had worn out his welcome with his teammates. The effects would carry over into the 1899 season.

With the war on Americans’ minds and public interest in the Temple Cup diminished by second-place teams winning three of the four series, there was little interest in postseason play. Both the Orioles and the Reds rejected Selee’s challenge to play a nine-game exhibition series. Most players seemed to agree that the new, longer season was just too long.

RICHARD RIIS is a writer, researcher, and genealogist with an abiding interest in baseball since he beheld his first baseball card in 1964. In addition to contributing to the SABR BioProject and 10 SABR books, he has been a contributing editor for a popular music magazine and is presently working with his friend and former child star Pamelyn Ferdin on her memoirs. He lives in South Setauket, New York.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author also consulted a number of newspapers and the following:

Caruso, Gary. The Braves Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995).

Notes

1 “Soden and Selee,” Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express, January 23, 1898: 18.

2 “A New Brotherhood,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 6, 1898: 6.

3 David L. Fleitz, Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Little-Known Members of the Hall of Fame (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2004), 178.

4 “Boston’s New Pitcher,” Bryan (Texas) Daily Eagle, April 13, 1898: 2.

5 “The National Game,” Dollar Weekly News (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), January 8, 1898: 6.

6 “Sporting Notes,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) News, April 2, 1898: 3.

7 “Disgraceful Conduct of the Crowd at the Polo Grounds,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 17, 1898: 31.

8 “Sporting Notes,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 20, 1898: 6.

9 “Baltimore 18, Boston 3,” Kansas City Journal, April 21, 1898: 5.

10 “Boston Wins Two Out of Three,” Sandusky (Ohio) Star-Journal, May 22, 1898: 4.

11 “Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 22, 1898: 30.

12 “Baseball Brevities,” Pittsburgh Press, May 24, 1898: 5.

13 “All Sorts,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 29, 1898: 18.

14 “Diamond Dust,” Washington Evening Times, May 12, 1898: 6.

15 L. Robert Davids, ed., Great Hitting Pitchers (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, second edition, 2012), 60.

16 “The League Batsmen,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 25, 1898: 5.

17 “Boston Did Not Make Hit or Run,” Philadelphia Times, July 9, 1898: 6.

18 “Frank Selee’s Views,” Wilkes-Barre Record, July 6, 1898: 3.

19 “Boston Protests,” Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express, August 21, 1898: 18.

20 “Base Ball Notes,” Scranton Republican, September 17, 1898: 3.

21 Patrick R. Redmond, The Irish and the Making of American Sport (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2014), 209.

22 “Base Ball Briefs,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln), October 30, 1898: 14.

23 “Happy Jack Stivetts,” Buffalo Enquirer, July 1, 1898: 6.

24 “Base Ball Notes,” Washington Evening Star, August 19, 1898: 9.

25 “Grand Baseball at Boston,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 23, 1898: 4.

26 “Tied in the Tenth,” North Adams (Massachusetts) Transcript, September 3, 1898: 4.

27 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves, 1871-1953 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004),

94.

28 T.H. Murnane, “Rough Going,” Boston Globe, September 5, 1898: 5.

29 Ibid.

30 “Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 12, 1898: 3.

31 “Seven Lost Money,” Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express, October 1, 1898: 10.

32 “Chalk Up One,” Boston Globe, October 4, 1898: 9.

33 Ibid.

34 David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball (New York: Donald I. Fine Books, 1997), 606.