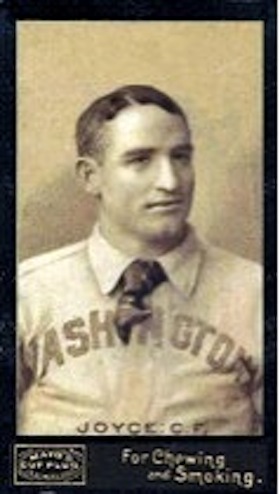

Bill Joyce

A prominent third baseman of the 1890s, Bill Joyce hit for average and power, and drew a lot of walks; his .435 career on-base percentage ranks seventh all-time.1 He was a smart and magnetic leader who inspired his teams with his aggressive style of play, though his disputes with umpires were excessive. The oft-quoted Joyce entertained the press with his gift of gab, and in 1896 he was called “the most conspicuous character in baseball.”2

A prominent third baseman of the 1890s, Bill Joyce hit for average and power, and drew a lot of walks; his .435 career on-base percentage ranks seventh all-time.1 He was a smart and magnetic leader who inspired his teams with his aggressive style of play, though his disputes with umpires were excessive. The oft-quoted Joyce entertained the press with his gift of gab, and in 1896 he was called “the most conspicuous character in baseball.”2

A son of Irish immigrants,3 William Michael Joyce was born September 22, 1867, in St. Louis and grew up in Carondelet, the southernmost neighborhood of the city, along the Mississippi River. The Carondelet riverfront was “crowded with mammoth iron and zinc furnaces.”4 As a young man, Joyce worked in a rolling mill there and was dubbed “Scrappy.”5 The nickname fit and stuck with him throughout his life.

Joyce played briefly in the Western League in 1887. The next year the Fort Worth Gazette reported that he “is a savage hitter, a fine base runner, and has probably the best base ball head of any man” on the Fort Worth Panthers of the Texas League.6 On June 17, 1888, Joyce crushed a home run described as “the longest, hardest drive ever made on the Fort Worth grounds.”7 The Panthers failed financially and disbanded in late June. Joyce played for the New Orleans Pelicans in August.8

In 1889 Joyce captained the Houston team to a first-place finish in the Texas League.9 An example of his astute play occurred on July 14. He was on third base with two outs and two strikes on the batter when the pitcher walked toward home plate to receive the ball from the catcher. As soon as the pitcher turned to walk back to the pitcher’s box, Joyce took off from third and scored the tying run.10 Joyce batted only .235 for Houston (and .164 for Toledo after Houston’s season ended), but his power was sensational. Twice in 1889 he hit three home runs in a game.11 “In batting he is [as] ferocious as a tiger,” said Sporting Life, “and hits the ball with the fury of a whirlwind and generally lands it over the fence.”12

In December 1889, the St. Louis Browns played a team of Texas all-stars in Galveston.13 For years, Joyce had cheered for his hometown Browns. Now, playing opposite them on this Texas squad, he impressed Browns manager Charlie Comiskey.14 A month later, upon Comiskey’s recommendation, John Montgomery Ward signed Joyce to play for his Brooklyn team in the newly formed Players League.15

Joyce batted left-handed and threw right-handed. He was big for the era – 5-feet-11 and 185 pounds. “Although a heavy man, Joyce, of the Brooklyns, is a fast runner,” observed the Sporting Life.16 He stole 43 bases in his rookie season, and with a keen eye, led the Players League with 123 walks. As a third baseman, he was a work in progress; his 107 errors were second-most in the league.

The Players League folded after one season, and Joyce joined the Boston Reds of the American Association. On May 18, 1891, he homered and tripled in a win over Louisville; his four-bagger was only the second ball ever hit over the right-field fence at the Boston ballpark.17 On July 2, he fractured his ankle while attempting to steal second base and was sidelined for three months.18

The American Association dissolved, and Joyce was reunited with John Ward in 1892 on the Brooklyn Grooms of the National League. But Joyce’s fielding was erratic and his hitting mediocre, and he was criticized for dirty play.19 On several occasions, he was called out for intentional interference, prompting one East Coast reporter to call him “a St. Louis hoodlum.”20 Joyce deserved the label in a game against the New York Giants:

“He was at bat and hit up a foul fly that [Jack] Doyle ran for. As usual with catchers when starting for a fly, Doyle threw off his mask and flung it on the ground. It rolled against the dainty foot of Mr. Joyce. … Joyce turned savagely, gave the mask a withering look of scorn and rage, and then lifting his bat he dealt the innocent mask a crushing blow, knocking it into a cocked hat, while poor Doyle, who had missed the fly, looked on in open-mouthed astonishment. The wires were so bent and twisted that Doyle couldn’t get it on.”21

The Brooklyn Grooms traded Joyce to the Washington Senators in the offseason, but he refused to play for the Senators at the salary offered and held out for the entire 1893 season. Reportedly, he spent much of that summer betting on horse races in St. Louis and hanging out with Alderman Jim Cronin, a lieutenant of Edward Butler, the city’s Irish political boss.22

Joyce finally signed with the Senators in the spring of 1894, and was named the team captain.23 The Senators had finished dead last the year before, and Washington fans hoped for a turnaround under Captain Joyce and new manager Gus Schmelz. The team’s new uniforms promised a fresh start – “shirts of dark blue with garnet sleeves,” “brilliant red stockings,” and “red and black caps” – though, in the opinion of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, these “costumes” were both startling and unattractive.24

Praised as “an intelligent, energetic and aggressive captain,” Joyce had one obvious fault: He was “a kicker from Kickersville,” who obsessively and persistently protested umpires’ calls.25 On May 1, 1894, his incessant kicking resulted in the forfeiture of a game to the Brooklyn Grooms. Worse, after the game he and several teammates followed the umpire into the dressing room spouting “obscene and blackguard language.”26 It was an “act of hoodlums,” wrote Henry Chadwick, the 69-year-old “Father of Baseball.”27

While batting on May 10, Joyce objected to a called strike and “threw his bat at the umpire;” the ump “retorted by flinging it back against Joyce’s shins.”28 But aside from the wrangling, Joyce had become an outstanding hitter. He recorded a career-high batting average of .355 in 1894, and clubbed 17 home runs, tied for second most in the league. On August 20, he hammered three homers in an 8-7 defeat of Louisville, and his bomb on September 18 was the longest home run ever hit at the Louisville ballpark.29 The Senators, though, struggled as a team and finished in 11th place in the 12-team National League.

In 1895 the Senators improved to 10th place. Joyce batted .311 and tied for the league lead with 96 walks. He again hit 17 home runs, making him the first major leaguer to hit 15 or more home runs in consecutive seasons.30 He homered twice off Cy Young in 1895, and once each off Amos Rusie and Kid Nichols, all future Hall of Famers. Joyce’s homer off Harry Staley on July 19 was the longest home run ever hit at the St. Louis ballpark; it cleared the high fence in right field by 30 feet.31 “Joyce used a blue-tipped bat, and the blue tip made many pitchers nervous when he strode to the plate, swinging the big stick.”32 He rarely bunted. “No infield taps for me,” he said. “Bang ‘em out and let the outfielders run.”33

Joyce was popular with his teammates and with Washington fans, who admired his “never-say-die spirit,”34 and he charmed the press with his humor. Sporting Life called him “the real funny man of the base ball world.”35

He displayed that sense of humor when he analyzed catcher Jack O’Connor, who operated a St. Louis grocery. Joyce kidded: “O’Connor sells round steaks that the amateur baseball catchers are wearing for chest protectors. O’Connor bought two goats, and is selling goats’ milk. He is feeding the animals on tomato cans. You can taste the tomatoes in the milk.”36

Joyce, at age 28, quipped about having prematurely graying hair: “Because I am gray the public believe I must be at least 38 or 40 years old. I have heard it said that I am as old as [Cap] Anson, and Anse, you know, listened to [George] Washington’s farewell address way back in 1782.”37

Joyce heard the French pronunciation of Nap Lajoie’s surname (“LAA-zhuh-way”) and scoffed, “His name is Joyce, the same as mine, but he’s ashamed to admit it.”38

On April 22, 1896, Joyce suffered a broken nose when he was struck in the face by a pitch.39 Six days later, he contributed four hits in a 9-5 Washington victory, including one of the longest home runs ever hit at the Baltimore ballpark.40 On May 30, he hit for the cycle in the first game of a doubleheader at Pittsburgh. And on June 26, he homered twice in a 9-3 triumph over the Baltimore Orioles; the victory improved the Senators’ won-lost record to 27-23, and the team, in fifth place, was called “the surprise of the season.”41 But the Senators dropped 22 of their next 29 games and plummeted to ninth place. Captain Joyce and Manager Schmelz were at odds over how to handle the team. To restore harmony, the Senators traded Joyce to the New York Giants on July 31, much to the dismay of the Washington faithful.42

On August 3, Joyce collected four hits for his new team and, as reported by the New York World, “one of ‘Scrappy’s’ chances [at third base] was a difficult fly which he picked off the left-field picket fence, the bleachers arising en masse and going wild.”43

“Scrappy Joyce may be an uncertain quantity on grounds balls,” said Tommy Dowd of the St. Louis Browns, “but when it comes to flies he never had a superior. He’s death to a fly ball.”44

The Giants had compiled a lackluster 36-53 record under manager Arthur Irwin when Joyce took over as captain and manager on August 8. He sparked the team to a 28-14 record over the remainder of the season and was suddenly the toast of New York. Though he directed a second-division squad, he was “full of fight as if first place depended upon every game.”45

His spirit endeared him to Giants fans. Sportswriter Tim Murnane said: “Billy Joyce is a natural-born baseball captain. He not only takes all kinds of chances to win, but he can see and play on an opponent’s weakness like a violin player picking an ‘E’ string. Joyce was continually talking to pitchers and gave them many good points, and this pays in close scores, where brain work plays an important part.”46

Joyce was the foremost practitioner of a style of a play that could be called “Scrappy Ball.” In his words, “a scrappy ballplayer is not a rowdy or a fist fighter – he’s a hustling, brainy fellow who knows the game coming and going, is on the job every minute, quick to take advantage of any mistakes of the oppositions or to demand of the umpire what he considers is coming to him.”47

It was this last point for which Joyce was criticized. Henry Chadwick scolded him for his “pernicious habit of stupid kicking.”48

“Joyce goes too far,” said Orioles manager Ned Hanlon. “He is utterly unreasonable. He kicks at every ball and every strike, and at every close decision against him.”49 Joyce even protested the amounts of the fines he incurred from his run-ins with umpires, claiming that he had not used indecent language, and so he could not be fined more than $10 per incident under league rules.50

Joyce’s claim was absurd; he routinely vented his anger in “long, lurid streaks of sulphurous blue.”51 His foul tongue, one of many in baseball, inspired the National League to adopt a rule before the 1898 season called “A Measure for the Suppression of Obscene, Indecent and Vulgar Language upon the Ball Field,” which threatened to ban for life any player found guilty of “villainously filthy language.”52

“Understand me, I favor the suppression of rowdyism, profanity and obscenity on the field, but I don’t propose to stand like a cigar sign and see my team robbed by incompetent umpires,”53 Joyce said.

At Pittsburgh on May 18, 1897, Joyce slugged four triples in one game.54 (He is one of only two players to accomplish this feat in major-league history through 2015.55 The other player to do so was George Strief of the Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association. He achieved the feat on June 25, 1885.)

Joyce led the Giants to an impressive third-place finish in 1897, and the following spring he said, “I think without a doubt we will land the pennant.”56 But the 1898 season was tumultuous and disappointing, and Joyce lost control of himself and his team. In a 13-4 loss at Cincinnati on May 27, Joyce “fumed and raged like a maniac” “after every error made by his team.”57

According to Sporting Life, “the club was listless,” and Joyce was continually “nagging at his men” with “complaints and tirades.”58 On June 3, Joyce was playing first base when Cincinnati’s Jake Beckley bunted down the first-base line. As Joyce fielded the ball, Beckley collided with him; in retaliation, Joyce fired the ball at Beckley’s head, striking him behind the ear. His misdeed was widely condemned, yet Joyce, in his “apology,” argued that Beckley had it coming to him.59

Giants owner Andrew Freedman decided a change was in order and hired Cap Anson to replace Joyce as manager on June 11.60 But Anson lasted only 22 games (reportedly, he and the volatile Freedman clashed61), and Joyce was reinstated on July 7. The Giants responded with a 29-10 record over the next month and a half, but dissension grew,62 and in the games after August 22, the team’s record was 17-29. Along the way, Joyce lost the support of Giants fans and the New York press.63

The low point came in Washington on September 29. The Giants trailed the Senators, 12-1, in the seventh inning when umpire Tommy Connolly ejected Giants catcher Jack Warner for arguing a call. To protest the ejection, Joyce made a farce of the game by shifting his players to unfamiliar positions, including himself to right field.

“Man after man [on the Senators] would come to the bat, hit the ball and run the bases at will, while the misfits filling the positions were [deliberately] making fools out of themselves throwing the ball around the lot.”64

The Washington Times declared, “Nothing more disgraceful was ever seen on a ball field, and no penalty known in baseball law would be adequate punishment for the offender, Bill Joyce. … The Giants looked upon the proceedings as a huge joke, and ‘Scrappy Bill’ from the right garden smiled with ghoulish glee.”65 The umpires “endured the disgraceful exhibition for several minutes” before the game was called, and the Giants “left the field amid the jeers of the spectators.”66

After the season Joyce said he was not to blame for the Giants’ “punk finish,” and he blamed Freedman for not spending money to acquire good players.67 As expected, Freedman chose not to bring Joyce back for the 1899 season. Joyce’s major-league career had come to an inglorious end.

In 1899 Joyce stayed in shape by practicing with the St. Louis Perfectos, a NL team managed by his friend Patsy Tebeau, but declared his retirement from the game in December at the age of 32.68 He opened a saloon in St. Louis with Tebeau as his business partner, and operated it for a decade; the enterprise was quite profitable.69 A longtime bachelor, Joyce, at age 41, married 34-year-old Adele Walters in 1908.70

In 1911 Joyce became the owner and manager of the Missoula (Montana) Scrappers of the newly formed Class D Union Association. In a game in Salt Lake City on April 27, Joyce “was chased off the coaching line for saying unkind things” about the umpire.71 What worked in the majors in the 1890s did not work in a low minor league in 1911, and it seems that as manager, he did more harm than good. In August the Scrappers were firmly in last place, with a 29-72 record, when Joyce “finally heeded the plea of the local fans that he remain out of uniform and off the playing field.”72 The fans did not like his “old-fashioned methods.”73 Unable to pay the players after July 15, Joyce forfeited the franchise.74

Joyce served as a scout for the St. Louis Terriers of the Federal League in 1914 and 1915, and for the St. Louis Browns of the American League in 1916.75 According to US census records, he was a watchman for an oil company in St. Louis in 1920, and a smoke inspector for the city in 1930.

On May 8, 1941, Joyce died in St. Louis, at the age of 73. He was buried in that city’s historic Bellefontaine Cemetery. One can imagine his protest to St. Peter if he was denied at the pearly gates. He would have kicked like hell.

Notes

1 http://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/onbase_perc_career.shtml. Accessed May 1, 2016.

2 O.P. Caylor, “Caylor’s Ball Gossip,” Logansport (Indiana) Pharos-Tribune, September 26, 1896.

3 1900 US Census.

4 NiNi Harris, A History of Carondelet (St. Louis: Patrice Press, 1991), 41.

5 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 26, 1897.

6 Fort Worth (Texas) Gazette, April 8, 1888.

7 Fort Worth Gazette, June 18, 1888.

8 New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 29, 1888; Sporting Life, September 12, 1888.

9 Houston Post, December 21, 1913.

10 Galveston (Texas) Daily News, July 16, 1889.

11 Sporting Life, May 8 and September 4, 1889. On May 3, 1889, Joyce homered three times for Houston against Austin, and in late August 1889, he homered three times for Toledo against Toronto.

12 Sporting Life, July 31, 1889.

13 Galveston Daily News, December 12, 1889.

14 Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Record, October 20, 1897.

15 Sporting Life, January 29, 1890; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 9, 1890.

16 Sporting Life, April 19, 1890.

17 Sporting Life, May 23, 1891.

18 Sporting Life, July 11 and October 10, 1891.

19 Sporting Life, May 28, 1892.

20 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 28, 1892.

21 Sporting Life, July 2, 1892.

22 Sporting Life, July 1 and September 2, 1893; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 12, 1911.

23 Sporting Life, April 7, 1894.

24 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 11 and July 29, 1894.

25 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 23, 1894; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 2, 1894.

26 Sporting Life, May 12, 1894.

27 Ibid.

28 Sporting Life, May 19, 1894.

29 Sporting Life, August 25 and September 22, 1894.

30 Christopher D. Green, “Baseball’s First Power Surge: Home Runs in the Late 19th-Century Major Leagues,” Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2011, http://sabr.org/research/baseball-s-first-power-surge-home-runs-late-19th-century-major-leagues.

31 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 20, 1895.

32 The Sporting News, May 15, 1941.

33 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 14, 1906.

34 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 10, 1895; Sporting Life, November 30, 1895.

35 Sporting Life, March 21, 1896.

36 St. Paul (Minnesota) Globe, March 15, 1896.

37 Boston Post, July 5, 1896. George Washington gave his farewell address in 1796. Cap Anson was born in 1852.

38 Cincinnati Enquirer, August 20, 1896.

39 Sporting Life, April 25 and May 2, 1896.

40 Sporting Life, May 2, 1896.

41 Sporting Life, June 27, 1896.

42 Washington Evening Star, August 1, 1896.

43 New York World, August 4, 1896.

44 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 2, 1896.

45 Sporting Life, September 26, 1896.

46 The Sporting News, August 29, 1896.

47 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 14, 1909.

48 The Sporting News, August 29, 1896.

49 Sporting Life, September 26, 1896.

50 Sporting Life, September 12, 1896.

51 Sporting Life, September 19, 1896.

52 Henry Chadwick, ed., Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide (New York: American Sports Publishing Co., 1898), 195-198.

53 Cincinnati Enquirer, April 18, 1898.

54 Sporting Life, May 22, 1897.

55 http://www.baseball-almanac.com/recbooks/rb_trip1.shtml. Accessed June 11, 2016.

56 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 14, 1898.

57 Hamilton (Ohio) Journal News, May 28, 1898.

58 Sporting Life, June 4, 1898.

59 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 4 and 7, 1898.

60 Though Anson replaced Joyce as manager, Joyce continued as a player on the team.

61 Sporting Life, July 16, 1898.

62 Sporting Life, September 24, 1898; Louisville Courier-Journal, October 5, 1898.

63 New York World, September 27, 1898.

64 Sporting Life, October 8, 1898.

65 Washington Times, September 30, 1898.

66 Washington Evening Star, September 30, 1898.

67 Buffalo Evening News, October 17, 1898.

68 Sporting Life, July 22, 1899; Scranton (Pennsylvania) Republican, December 9, 1899.

69 Sporting Life, January 20, 1900; January 5, 1901; May 10, 1902; February 21, 1903. After three years, Joyce bought Tebeau’s stake in the saloon, ending their partnership.

70 Macoupin County Enquirer (Carlinville, Illinois), December 2, 1908.

71 Anaconda (Montana) Standard, April 28, 1911.

72 Salt Lake Tribune, August 10, 1911.

73 Salt Lake Tribune, August 13, 1911.

74 The Sporting News, August 24, 1911; Sporting Life, January 20, 1912.

75 Sporting Life, September 5, 1914; July 3, 1915; January 22, 1916.

Full Name

William Michael Joyce

Born

September 22, 1867 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

May 8, 1941 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.