Before We Forget: The Birth, Life, and Death of The Sporting News Research Center

This article was written by Steve Gietschier

This article was published in Spring 2020 Baseball Research Journal

This article was honored as a 2021 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award winner.

More than a decade has passed since American City Business Journals (ACBJ), a subsidiary of Advance Media, the company that bought the Sporting News in 2006, moved the publication’s editorial office from St. Louis to Charlotte, North Carolina, and closed The Sporting News Research Center. This essay is an attempt to tell the story of how the research center came to be, what it accomplished over 22 years, and how it met its demise. My recollections have been aided by those of Jim Meier, who worked for TSN for nearly 12 years and without whose expertise we would have achieved much less.

How It Began

Sometime before the Sporting News Publishing Company marked its centennial on March 17, 1986, president and chief executive officer Richard Waters recognized that his domain included a variety of historical artifacts and research materials that needed and deserved better care than the company had provided to that point. Waters contacted his friend, Charles P. Korr, professor of history at the University of Missouri–St. Louis (UMSL) and later the author of The End of Baseball as We Knew It: The Players Union, 1960-81, and asked for advice.

Korr suggested Waters consult with Anne Kenney, the director of special collections at UMSL and a professional skilled in caring for historical materials. Kenney recommended that Waters hire an archivist, preferably one familiar with sports and sports history. She helped craft the job description and the advertisement published in the Oct/Nov 1985 newsletter of the Society of American Archivists.

I read that advertisement and mailed my letter of application on New Year’s Eve, 1985. At the time I was both a historian, with a doctorate from Ohio State, and an archivist, having worked for three years at the Ohio Historical Society and more than seven years at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History. I was neither a sports historian nor a sports archivist. I didn’t even know if those two fields existed. I was, however, a very committed sports fan.

To prepare for the interview I hoped would come, I began buying The Sporting News at a local drugstore. I had read the publication on and off as a youngster but, in truth, had focused most of my sports reading on books and Sports Illustrated. Fortunately, on the very date on which TSN became a hundred years old, SI published a long, celebratory essay by the inimitable Roy Blount Jr. Through it, I learned a lot about TSN’s past and especially about a man named Paul Mac Farlane, a former copy editor turned company historian.

Shortly thereafter, TSN’s human resources director, Char Strahinic, invited me to St. Louis for an interview. This full-day experience took place on April Fool’s Day, 1986. In the morning, I met with Waters, chief financial officer Jim Booth, and editor Tom Barnidge. I spent time in the afternoon with Mac Farlane and Lowell Reidenbaugh, who had just written The Sporting News: The First Hundred Years, 1886-1986, a hardcover, coffee table book that would become my concordance to the “Bible of Baseball.” Lowell and I talked mostly about the Civil War, his other passion besides baseball. As for Mac Farlane, we talked mostly about his other passion, the Boston Red Sox.

I returned to South Carolina enthusiastic, believing I had a good shot at the job. How many other people could there be, I wondered, who were historians, archivists, and sports fans? Very few, apparently, because within a few days, Char called with a job offer that I accepted. I entered the company’s offices for the first time as an employee on the Tuesday after Labor Day, 1986.

Where It Began

The building the company owned at 1212 N. Lindbergh Boulevard in suburban St. Louis was a big place, 41,000 square feet, the company’s first home since leaving downtown in 1969. Offices located around the perimeter were huge and had ceiling-to-floor windows. The editorial staff worked in two open spaces bereft of walls or cubicles with a telephone and a computer terminal on every desk. The wallpaper was custom-made, reproducing pages from TSN’s inaugural issue, and the carpeting was a very vibrant burnt orange. Along the walls were rows of book shelves and file cabinets, each with drawers painted alternately the same burnt orange and beige.

Adjacent to the editorial areas was the lunch room — or “corporate dining area,” as some insisted it be called. Its wallpaper was also custom-made, featuring baseballs on a sky-blue background. In the past, I learned, when major league players had visited the building, they were sometimes persuaded to autograph a wallpaper baseball.

Fastened to these walls were wooden racks that held sets of the commemorative bats produced by Hillerich & Bradsby to mark each All-Star Game and World Series. We had complete runs of these bats plus dozens of extras stored in a back room: a warehouse from which we mailed books, guides, and registers and retained boxes of back issues of TSN itself dating back more than 50 years.

Mac Farlane — or Mac, as everyone called him — had an interior office that measured about fifteen feet by twelve feet with no windows. That was where I was supposed to work, but it was too cluttered. Blount called this space a “historical storehouse.” True. Mac’s desk was overwhelmed with books, letters, envelopes, scraps of paper, coffee mugs, pens, pencils, and a standard typewriter. The adjacent shelves groaned under a century of tradition. In front of his desk, partially blocking the doorway, was a table-top model of Fenway Park, maybe three feet by four feet, around which everyone who wanted to enter had to maneuver. Under his desk and unknown to almost no one, sat a hidden case of Laiphroaig scotch whisky, delivered once a year by a mysterious stranger.

I found work space in the room adjacent to Mac’s, the vault. It really was a vault. Its entrance was through a bank vault door, the combination to which was one of the sacred baseball numbers to which Mac paid homage, 4-0-6. In the vault, the company kept precious things: Beadle guides, Spalding and Reach guides, a copy of The Base Ball Player’s Pocket Companion, published in 1859, and two file cabinets — called fireproof because they were made of steel and concrete. This is where I went to work each day, opening the combination lock and sitting at a small desk wedged into impossibly crammed space.

What to Do?

The job description called for someone to be responsible “for preserving and maintaining a sports collection, documents and reports, designing and implementing retrieval and storage systems, and assisting sales and marketing staffs with historical presentations,” but how to do these things was up to me. Technically, the position was situated within the editorial department, and Barnidge was my boss, but he was content to let me fashion the job as I saw fit.

I spent my first weeks getting to know everyone else and understanding that the company included several departments besides human resources and editorial: circulation, advertising, production, books, accounting, public relations, and customer service. My goal was to make sure that everyone knew who I was and that I was available as a resource to assist them however appropriately. The closest relationships were with public relations and advertising, particularly when the ad sales staff tried to use the company’s history as a tool to sell advertising pages. In one instance I recall, we helped the Chicago sales office put together some trivia questions on Chicago sports history.

I learned that the editorial staff was divided into two groups: a bunch of mostly senior people responsible for “putting out the paper,” as the saying went, and a group of younger people who worked on the books — guides, registers, record books, hardcover books, and season preview magazines called “yearbooks.” Both concentrated on the sports we called the Big Six: baseball, college and pro football, college and pro basketball, and hockey. Most of both groups were men, and most had no idea who I was or what I was supposed to do. Many were fixed in their ways.

Our Holdings

Mac’s office and the vault contained only some of the company’s historical materials. He controlled complete runs of staples like the Spalding Guide, the Reach Guide, the Baseball Blue Book, the American League Red Book, the National League Green Book, the Little Red Book of Baseball, and others. Outside his office were open shelves on which were stored several thousand trade books in complete disarray. Scattered about were periodicals, media guides, and our own guides, registers, and record books.

File cabinets adjacent to the newsroom held our photographs, probably more than 600,000 prints, mostly black-and-white, plus a smattering of negatives. File cabinets near the book editors held a resource of incalculable value: our clipping files.

In 1986, TSN subscribed to over a hundred daily newspapers. There were stacks of newspapers all over the newsroom. Editors, in their spare time, read these papers and clipped relevant articles. An editorial assistant placed each clipping in the proper brown envelope within a massive filing system for untold thousands of clippings, some dating from the first years of the twentieth century or even earlier. Some clips were filed biographically, but there was also an elaborate — and yet unindexed — subject file. These clips covered not just baseball, but other sports as well. The file cabinets that housed the clips stood six drawers high, and there were, memory suggests, more than fifty cabinets.

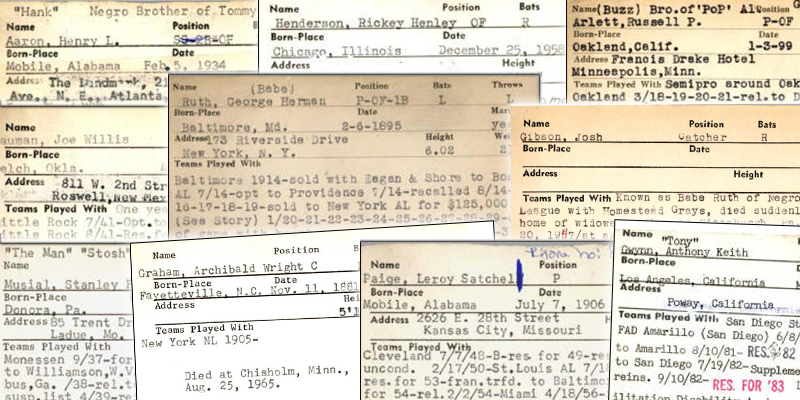

The same editorial assistant also updated our file of player contract cards: 3×5 index cards on which we recorded the contract history of every professional baseball player. Our staff used these cards, but so did I, learning how to document minor league careers for customers who wrote inquiring about family members. SABR founder Ray Nemec maintained his own set of cards, and we frequently worked together to fill in gaps. With a player’s contract history in hand, it was a simple task to check the relevant guides and develop a player’s statistical record. Mac Farlane had told Blount that “the FBI uses this,” referring to the card file. I could not say.

Buried within the clipping files was an extraordinary collection of player questionnaires. From the early days of the Baseball Register, first published in 1940, our correspondents would ask players in spring training to fill out biographical questionnaires. They did so, year after year, creating a trove of data in the players’ own hands that were filed in each player’s folder.

Also sitting on the shelves were two boxes of correspondence between the Spinks, Taylor and his son, C.C. Johnson Spink, and Ty Cobb. Nearly a hundred letters passed back and forth, most dating from the 1950s until 1961, the year of Cobb’s death.

The First Archives

Waters soon said that our goal was to construct an addition to the existing building that would become the new, professionalized archives. We began meeting with an architect, a man whose practice had included designing Burger King restaurants and an addition to the Waters’ residence. We developed a floor plan that met some of our needs: office space, storage space maximized by a system of compact shelving, and work tables for staff members and — I hoped — outside researchers. Waters also said this addition would be my work space, but not Mac’s. As construction proceeded, Mac would walk back to inspect it, and he began to wonder if it was going to be big enough for the two of us. My job was to deflect such questions. No one else told him his days were numbered.

When construction was completed, the treasures moved from the vault and Mac’s office into the new space. It was awkward, to say the least. The new space opened on April 8, 1988, complete with its own air conditioning system. Mac’s last day came a week later.

Opening the new archives gave us a chance to begin treating some of our research materials with the respect they deserved. Two examples will suffice. To prepare the coffee table books the company was publishing regularly, the book editors had been using what we called “bound volumes,” all the issues of a full year of TSN bound between hard covers. Obviously, newsprint does not age well, and repeated use of the bound volumes from our early years was causing substantial and irreversible deterioration. Night after night, the cleaning crew had to vacuum myriad bits of paper from the floor.

We had TSN on microfilm, but no way to use it. Once we had archival space, we bought a microfilm reader-printer, trained the editors in how it worked, and retired the bound volumes from use. We were also able to gather together the sports books littering shelves here and there and re-shelve them on our compact shelving. We no longer had a random collection of books. We had a library.

On the other hand, the budget that built the new archives had a limit, and so, too, did the space we created. The clipping files remained where they were, and so did the photo files. Frankly, I could not imagine a budget large enough to create a space that could house everything we held. The key toward securing these materials was to assert control. Emptying the vault and Mac’s office helped. So, too, did the requirement that we lock the archives upon leaving each night.

Editors soon learned that I was the resource person for finding what they needed. To give one more example, I removed the player questionnaires from the clipping files and brought them together in the new archives: 50 questionnaires in an acid-free folder, 13 folders in an acid-free archival box, 47 boxes in all. Still, I was pretty much operating on my own without making any real contribution to our editorial products. Not until John Rawlings succeeded Barnidge and refashioned the editorial staff did I become part of the editorial team that planned each issue and begin to do research that helped writers and editors prepare stories for publication.

TSN and SABR

I attended my first SABR convention when the organization met in St. Louis for the second time in 1992. Frankly, I was leery about going, guessing, incorrectly as it turned out, that once people knew I worked for TSN, I would be overwhelmed with requests for research assistance. Such was not the case. We also arranged for convention attendees to tour our office, sort of a trip to a baseball mecca. We thought we had planned for one bus with thirty people whom we would divide into three tour groups of ten. To our great surprise, three buses showed up, each with thirty people. It was time to scramble, which we did, making a lot of SABR friends in the process.

The Conlons

Early on, Mac had told me about those two fireproof file cabinets. Inside were his pride and joy, glass-plate negatives, some 5×7 and some 4×5, all of them photographs taken by Charles Martin Conlon. This was a name I did not know, but I soon began to appreciate Conlon’s skill as a photographer and his place in baseball’s visual history. Moreover, I learned that while these file cabinets contained glass-plate negatives, our regular photo files contained many other Conlon photographs, some vintage prints made by Conlon himself, some more recent prints made by others, and thousands of negatives shot on acetate film after Conlon switched from glass plates. We pulled all the Conlons together in one place and counted more than seven thousand images, truly one of baseball’s grandest treasures.

Some Conlon prints had already been on public display. The National Portrait Gallery, part of the Smithsonian Institution, had mounted a Conlon exhibit called “Baseball Immortals” that opened in 1984. Perhaps the Smithsonian had been aware that a small St. Louis company, World Wide Sports, had used Conlon’s images to produce a set of one hundred oversized baseball cards in 1981 and a set of 60 cards to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the All-Star Game in 1983. The Smithsonian made exhibit prints directly from the glass plates and developed a new set of 60 cards.

Marketed under the logo “Baseball Americana,” these cards plus posters and other ancillary products were produced by another St. Louis company, Marketcom, whose principal business was oversize posters of SI covers. After the Washington show closed, the exhibit joined the Smithsonian’s SITES program and traveled around the country for two years. After that, all the “Baseball Americana” materials became Marketcom’s property.

How did TSN come to own the Conlons? No one around in 1986 knew for sure. We did know that Conlon began taking pictures in 1904, stopped in 1942, and died in 1945. All we could surmise, absent any paperwork, was that some time after Conlon stopped taking pictures, he sold his collection to TSN. How everything moved from suburban New York, where Conlon lived, to St. Louis remained a mystery.

After spending a little time with his life’s work, I became convinced of two things. First, the negatives needed help from professional photo conservators. And second, his best images deserved to be published in a book.

Conlon was frugal. To store his negatives, he used ordinary cardboard boxes. He placed each negative in an envelope cut in half and wrote on it the player’s last name, an abbreviation for his team, and two digits for the year, say, “23,” for 1923. Frequently, he reused these envelopes, scribbling out the data on one side and writing new information on the other, indicating, so it seemed, that he must have destroyed hundreds, if not thousands, of negatives.

What survived needed work. We bought archival-quality sleeves and boxes and, without a computer, wrote a thorough database, but that was only the beginning. One of the nation’s foremost paper conservators, Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler, suggested an art conservator, Connie McCabe. She worked at the National Gallery of Art and co-owned, with Stephen Small, a business called PPS, Photo Preservation Services. Speaking to me on the telephone, Connie was far from convinced that these photos were worth her expertise, but PPS needed the work, and she agreed to take on the project. The trip from St. Louis to Alexandria, Virginia, in a Ford Taurus station wagon was fraught with the fear of a rear-end collision, but we made it unscratched.

PPS cleaned the negatives, re-shot them to archival standards, produced a second generation called inter-positives and a third generation called reproduction duplicates. Every use to which we put the Conlons after that used this iteration. We retired the originals, regarding them as precious artifacts. Just as significantly, McCabe, once she saw the negatives, fell in love with them as works of art. She was not a baseball fan, but her brother Neal, a postal employee in Los Angeles with a degree in music composition, was. When Connie told Neal that she was working on an extraordinary collection of baseball images, his skepticism duplicated hers from a few months previous. But he visited her and changed his mind. Thus began the saga that led to the publication of Baseball’s Golden Age: The Photographs of Charles M. Conlon, perhaps the most stunning book of baseball photography ever published.

A book proposal went to TSN’s own book department, experienced in the production of low-cost, hardcover books that did not sell especially well. The best-selling title had been Take Me Out to the Ball Park, reproducing illustrations by Gene Mack and Amadee Wohlschlaeger. The proposal suggested that a book of Conlon photographs should be produced to a higher standard and printed on glossy paper. The head of the book department, as skeptical as Connie and Neal had been, rejected the proposal, but she agreed to forward the idea to a New York-based publisher called Harry N. Abrams. TSN had been a Times Mirror company since 1977, and so was Abrams, and their specialty was high-end art books. Somehow, Abrams said yes, but the editor they assigned to the project was less than enthusiastic. Conlon got his book. Neal selected the pictures and wrote the captions, Connie did the technical work, but the editor insisted that the McCabes’ suggested title, The Baseball Photographer, the title of an essay Conlon himself wrote, should be abandoned for the more prosaic Baseball’s Golden Age. Abrams published the book and even hosted a launch party in New York but did not see fit to invite the authors to celebrate their own work. Instead, TSN assigned me to represent the book. I got to talk about it on live television with sportscaster Len Berman, and I got the party’s special guests, former players Tommie Agee and Ed Kranepool, to autograph a copy. The book got excellent reviews. It sold very well and even appeared in a paperback edition, highly unusual for an art book. And it led eventually to a sequel, The Big Show: Charles M. Conlon’s Golden Age Baseball Photographs, that had an ever longer tumultuous and serpentine genesis.

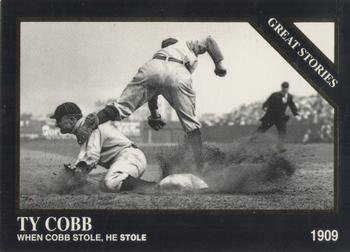

The Cobb Slide Photo

Conlon’s most famous photo shows Ty Cobb sliding into third baseman Jimmy Austin. Well before the McCabes’ book was published, this image had been reproduced many times, never credited to Conlon or TSN. What no one knew until one auspicious day was that the photo as published was a cropped version of the original. On that day, a woman from our accounting department walked into the archives and said, “We are clearing out a safe. Do you want this?” She handed me a brown, padded mailing envelope on which was written in pencil “Cobb slide – original.” We knew we had this image on a 4×5 glass negative, but when I gingerly removed the contents of the envelope, I saw another glass plate, this one 5×7. The glass was cracked, but incredibly, the emulsion was still intact. We had, I knew, uncovered one of baseball’s most precious artifacts, the Cobb slide, not as it had been cropped, but as Conlon had photographed it. Connie McCabe repaired the glass, and Neal, working from the photo’s internal evidence, was able to date it precisely to July 23, 1910. Another treasure rescued.

Baseball Cards

Baseball’s Golden Age put Conlon on the map, but so, too, did “The Conlon Collection,” baseball cards produced by a company called MegaCards. Before the book’s publication, TSN received an inquiry: would we be interested in a multi-year set of baseball cards using Conlon photos? Yes, subject to obtaining the proper licenses. So began a project that was supposed to last five years, 330 cards per year, numbered consecutively. MegaCards issued full sets in 1991, 1992, 1993, and 1994, but in 1995, with baseball embroiled in a labor dispute, the company hedged its bets and released only 110 cards, withholding the other 220, subject to unfolding events. No more ever appeared.

Open for Research

Both the Ohio Historical Society and the South Carolina Department of Archives and History made their holdings available to the researching public. I expected to do the same in St. Louis, to allow researchers to use our resources, even though we were a private company. Little did I know that TSN had long held a proprietary attitude toward the information we held even to the point of restricting sales of a locally-produced microfilm edition. To my knowledge, the only researchers TSN had ever allowed inside had been Dorothy and Harold Seymour. One can only imagine the conversations that transpired between two titans of their trades, J.G. Taylor Spink and Dr. Harold Seymour.

Only some private companies have archives, and only a few of these are open to the public. Waters was amused that I wanted to open our facility to researchers, especially those working on books, and even more amused that I wanted to do so without charging visitors a fee. When I explained that most researchers’ books would not earn them much money, he was befuddled. “Why,” he asked, “would anyone write a book that won’t make any money?” Still, he placated me, “so long as you don’t neglect your other duties,” and we were able to announce that The Sporting News Archives, as we first called it, was open to researchers. They arrived slowly but rather steadily.

We were also able to extend the company’s internship program, which each summer took on college journalism students, to the archives. One of our interns later earned a doctorate in sport history. Another got a job in collegiate sports management. A third stayed with us for quite some time and worked quite nearly as a full-time employee. Later, two students in archival studies did internships with us.

Ken Burns and Baseball

When documentarian Ken Burns announced that Florentine Films’ next large project after The Civil War would cover the history of baseball, TSN got involved. We thought that our collection of photographs, Conlons included, would prove essential. Producer Lynn Novick and cinematographer Buddy Squires came to St. Louis for an extended visit. They took video of many photos, and TSN got a nice on-screen credit at the end of each episode. We also thought that we might be offered a chance to comment on the script and maybe even become one of Burns’ famous “talking heads,” but after critiquing a very early version of the script — maybe the first — no more came of that. Burns, TSN, and General Motors worked out a tripartite agreement. We gave Burns access to our photos at no charge. General Motors paid for an advertising supplement to our regular issue just before the film premiered in 1994. Burns agreed to make some personal appearances at TSN functions although no such occasions ever occurred. In similar fashion, we helped filmmaker Aviva Kempner as she worked on The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg, which made its debut in 1998.

Hiring Jim Meier

One revenue stream we were able to explore was licensing the use of our photos for a fee. We began to sell prints to individuals for personal use, and we hired a person, who stayed with us for a while, to develop a more robust market among authors, publishers, and commercial users. Expanding the breadth of the archives and turning it into a research center followed the company’s decision to hire another professional, Jim Meier, in 1995. Jim arrived with impeccable credentials. He was an athlete and a sports fan. He had a bachelor’s degree in economics and three master’s degrees in business, sports management, and library science, plus experience in a library. He complemented what we already had and enabled us to move forward.

In 1996, the company sold its headquarters and moved into leased space less than a quarter-mile away. Jim organized the move, working with a company skilled in moving library resources, so that the contents of each shelf at 1212 N. Lindbergh got to the right shelf at 10176 Corporate Square Drive. After we worked consecutive fifteen-hour days, the new research center was ready to go when the editorial staff returned to work on the next issue without any significant downtime.

Before Jim arrived, we had in place contracts to supply our content to the Nexis database and the LATimes syndicate. Jim assumed responsibility for fulfilling these contracts, and he wrote procedural manuals and trained others to do this work. He also expanded our photo licensing business, adding to it the sale of “Keepsake Covers” reproduced from the weekly, and increased annual revenues in this area to six figures.

Jim’s other contributions were substantial. He created a networked online catalog to our book collection, grown to more than ten thousand volumes, available to all editorial staff members. He developed a section of the TSN website called “The Vault” where he posted all sorts of historical data. He and I both sat on small committees, editorial content teams, that planned coverage of our various sports.

Jim also helped expand our effort to do public research, that is, answer queries that arrived by letter, by telephone call, and later, via email. We helped athletes, broadcasters, students, scholars, genealogists, and incarcerated people. We handled questions from around the world, and we let people do their research in person. I particularly remember one man who visited from Australia several Januarys in a row to do research on the National Football League.

The result of this policy are dozens of baseball books on shelves everywhere. Authors like to see their names on title pages. Archivists and librarians like to see their names on acknowledgments pages. Our names are in lots of books. For this honor, gratitude goes to the editors under whom we worked, Barnidge and Rawlings, and the presidents who followed Waters and allowed us to continue: Tom Osenton, Nick Niles, Jim Nuckols, and Rick Allen.

Paper of Record

Jim and I were regularly able to attend the annual conference of the Special Library Association where we were members of the News Division along with researchers and archivists from many other newspapers, magazines, and broadcast media. In San Antonio in 2001, we listened to a presentation from a Canadian firm called Cold North Wind. Their goal was to take newspapers that had been microfilmed but not digitized and convert the microfilm into digital files that would be full-text searchable and available online. Jim and I agreed, “This is for us.”

We had TSN on microfilm, of course, but there was no index, making searching tedious. Besides, Cold North Wind said that their product, Paper of Record, would bring our company revenue.

We set in motion a process that eventually added TSN to the Paper of Record database. Researchers gained easy access to it for a reasonable fee, and the search capability worked surprisingly well, given the uneven quality of the microfilm images. One of SABR’s most valuable membership perks is access to Paper of Record, largely because of the archives of TSN. (Google later acquired Cold North Wind, and SABR’s access to Paper of Record was suspended, but SABR worked with Google to reopen it as a member benefit.)

And Other Duties as Assigned

The editorial content of The Sporting News changed significantly as the company confronted competition from cable television and the Internet. From April 1990 until October 1997, I wrote a biweekly book review column, showcasing the work of SABR members and other sports authors. For an additional year, the column continued online and as an occasional part of a print column called “My Turn.”

TSN redesigned the Baseball Guide in 1992, and I took over writing the “Year in Review” essay from the beloved Cliff Kachline. I wrote this essay until the Guide’s final edition in 2006. Bittersweet though the demise of the Guide was, it was pleasant to know that the idea of an annual guide and an annual year-in-review essay had originated with Henry Chadwick, the “Father of Baseball,” who published the first edition of Beadle’s Dime Base Ball Player in 1860.

Similarly, late in 2003, the company asked me to assume editorship of The Complete Baseball Record Book. Knowing nothing about how to do this, I said yes. Fortunately, SABR friends came to the rescue, especially Pete Palmer, who had been helping with the Record Book for years, and Lyle Spatz, then the chair of SABR’s Records Committee. A sensible decision was recruiting a roster of SABR volunteers, each of whom agreed to follow one team for the season in a plethora of records categories. Thanks to this help, the book improved every year. TSN published the final print edition in 2006 and produced two more after that as PDF files, made available on our website for no charge.

How It Ended

Perhaps the beginning of the end came in the late 1990s when the company ordered the sale of all our artifacts. We had previously sold an array of commemorative and souvenir items, most of them gifts to the Spinks, that had graced display cases in the lobby of 1212 N. Lindbergh, including autographed baseballs and photos, letters from presidents, and pieces of memorabilia once belonging to the American League’s founding president, Ban Johnson, such as his diploma from Marietta College.

In this second sale, anything that did not bear directly upon the company’s history or have research value had to go. There was no room for sentiment. We contracted with a sports auction house and devised a plan we hoped would maximize revenue. On the auction block went all the souvenir Louisville Sluggers and thousands of original illustrations that the country’s most prominent sports artists had submitted for publication.

The company’s ownership history is instructive as a guide to the further demise of the research center. The Spink family owned the company from its founding in 1886 until 1977 when the Times Mirror Company became the new owner. In 2000, Times Mirror sold to Vulcan Media, owned by Microsoft co-founder Paul G. Allen, and in 2006, Vulcan sold to Advance Media and ACBJ. Part of this last transaction was leaving leased space at Corporate Square Drive in May 2006 and moving to smaller leased space that had no room for a research center. We packed everything we had in bankers’ boxes, put a barcode label on every box, and sent them to an off-site storage facility from which we could retrieve materials as needed. The research center was closed.

The father-and-son executive duo that ran ACBJ said they would keep The Sporting News in St. Louis. Yet, within a year, they moved all phases of the operation except the editorial staff to Charlotte, and in July 2008, they transferred the editorial staff as well and adjusted the publication schedule from weekly to bi-weekly and later to monthly. In 2012, print publication ceased, and only digital publication remained.

In 2013, ACBJ entered into a joint venture with Perform Group, an international sports data company that bought 65 percent of the company at first and purchased ACBJ’s remaining stake in 2015.

The Legacy

Once ACBJ announced the move to Charlotte and said that I need not come along, we developed a proposal to keep the history of The Sporting News in St. Louis. We retrieved the bankers’ boxes from off-site and lined them up like coffins in a spare room. We approached three local universities, asking them if they would be willing to acquire the archives and create what might have been called the Sporting News Center for the Study of Sports in America. All three were receptive.

ACBJ executives were less enthusiastic. One hundred days after receiving the proposal, the CEO walked into the room where the materials were lying. He opened one box and said, “Oh, books about Ty Cobb. Ship them all to Charlotte.” Except for the bound volumes — whose safe transfer to the Missouri Historical Society, a St. Louis institution, ACBJ did approve — none of the research materials stayed in St. Louis. Everything went south.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch quoted another ACBJ executive on the future of the research center. “It is sad to see it leaving St. Louis, but it’s a happy time as well, to know that we’re able to keep it in the company,” he said. “From the company’s standpoint, this is a valuable resource — one that doesn’t exist anywhere else — and is a real benefit to what we do.”

Unfortunately, that “valuable resource” remains in Charlotte but unavailable to researchers. Tom Hufford, one of SABR’s founding members, was able to convince ACBJ to donate the player contract cards to SABR in 2013, and in November 2019 the Sporting News Player Contract Card Collection went live online, making available biographic details about the lives of over 180,000 major and minor league players and over 10,000 umpires and team executives.

Much more tragic was the fate of the photo collection, including the Conlons. In 2010, ACBJ sold the entire photo archives to Rogers Photo Archive for a reported $1 million. John Rogers faced numerous legal difficulties, and in August 2016, the Conlon negatives sold at auction to an anonymous buyer for $1,792,500. After the sale, I tried to offer my services to the buyer, but Heritage Auctions, the company that handled the sale, said it was unable to forward my offer.

One final, sad note. When the company was preparing to leave 1212 N. Lindbergh for 10176 Corporate Square Drive, we located roughly sixty boxes of correspondence and records dating from before 1977. These were, so to speak, the corporate archives of the Spink years, boxes that contained priceless material documenting the relationship between both Taylor Spink and Johnson Spink and executives throughout Organized Baseball. Without involving me, the company sent these boxes to an off-site storage facility and never retrieved them. Where exactly they went and what became of them is unknown.

With sustained corporate support, The Sporting News Research Center, developed from scratch, became one of the outstanding sports research facilities in North America. Our message to baseball researchers was this: “If you live in the East, by all means try to get to the National Baseball Library in Cooperstown. If you live in the West, consider the Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles [now LA84]. But if you live in the Midwest and can’t travel far, come to St. Louis.” Many did, and baseball scholarship is the richer for it.

STEVE GIETSCHIER taught history to undergraduates for 11 years, including courses on American sport and baseball. From 1986 until 2008, he worked for The Sporting News, responsible, with the help of many others, for developing an unorganized collection of historical materials into The Sporting News Research Center. He is the editor of “Replays, Rivalries, and Rumbles: The Most Iconic Moments in American Sports” (University of Illinois Press, 2017) and is a former member of the SABR Board of Directors.