Bud Adams, Roy Hofheinz, and the Astrodome Feud

This article was written by Robert Trumpbour

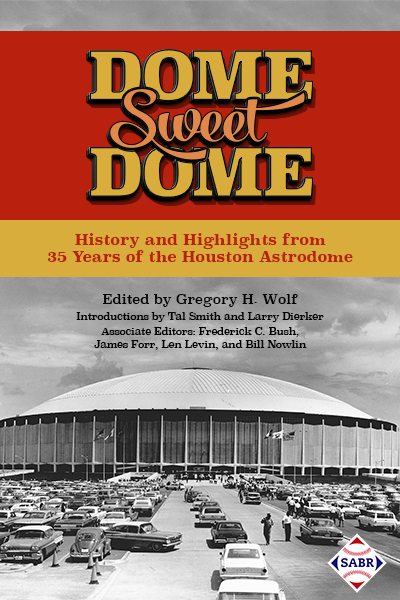

This article was published in Dome Sweet Dome: History and Highlights from 35 Years of the Houston Astrodome

When Roy Hofheinz took charge of the Astrodome project, he envisioned a venue that would host a broad range of activities. Before moving forward with the project, Hofheinz, a former state representative, judge, mayor, and entrepreneur, had worked with Buckminster Fuller to plan and design an indoor shopping mall that would feature a unique dome as part of its overall design. However, when a rival developer, Frank Sharp, edged him out in attracting anchor tenants, Hofheinz abandoned mall development entirely and immersed himself in the Astrodome’s construction.

When Roy Hofheinz took charge of the Astrodome project, he envisioned a venue that would host a broad range of activities. Before moving forward with the project, Hofheinz, a former state representative, judge, mayor, and entrepreneur, had worked with Buckminster Fuller to plan and design an indoor shopping mall that would feature a unique dome as part of its overall design. However, when a rival developer, Frank Sharp, edged him out in attracting anchor tenants, Hofheinz abandoned mall development entirely and immersed himself in the Astrodome’s construction.

As a youngster, Hofheinz worked in radio and organized social events in Houston that included such top-tier performers as famed Louis Armstrong. From extraordinarily humble beginnings, Hofheinz acquired a vast range of creative skills that allowed him to supervise the design of a new and luxurious facility that he envisioned as a sort of entrepreneurial town square. His goal was to build a unique massive indoor venue that would bring prominence to Houston while hosting baseball, football, the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, concerts, large-scale exhibitions, and numerous other special events.1

That vision was made more complex by Kenneth “Bud” Adams. Adams owned the Houston Oilers, a professional football franchise that was expected to play its games in the Astrodome in 1965, the year it opened. However, Adams’s team did not move into the facility until 1968, opting instead to play in less opulent outdoor venues.

During the lease negotiations with Hofheinz, Adams boldly proclaimed, “If the Astrodome is the eighth wonder of the world, surely its rent is the ninth wonder.”2 Needless to say, negotiations between Hofheinz and Adams did not go smoothly. The mercurial Adams tended to pinch pennies when he could, so the high cost of moving his team into the Astrodome was something he resisted.

The philosophic gulf between Roy Hofheinz and Bud Adams was wide, and that complicated the negotiating process. Both men were influenced by the Depression. Hofheinz was prone to surround himself in luxury, an understandable reaction to years of deprivation. He regarded investment in material goods as an index of success, extending that philosophy to publicly financed civic monuments. When Hofheinz unveiled the Astrodome, he justified his desire to favor opulence by asserting that after visiting the venue, “nobody can ever go back to Kalamazoo, Chicago, New York, you name it, and still think this town is bush league.”3

Adams was less predictable and more uneven in his spending patterns, though he tended to favor cost containment as a managerial strategy. Houston Chronicle sportswriter Ed Fowler asserted that Adams “couldn’t settle on a style for running his organization,” but when he hired staff, “the figure with the greatest say was usually a bean counter.”4

Nevertheless, the Oilers owner could spend in luxurious and dramatic ways. Before George Steinbrenner pioneered high-stakes free agency in baseball, Bud Adams was selectively going after high-profile talent in football. In an example, he dispatched Adrian Burke, his American Football League team’s attorney, to New Orleans, where he promptly signed Heisman Trophy-winning LSU running back Billy Cannon to a lucrative contract under the goalposts immediately after the 1960 Sugar Bowl game. Cannon’s three-year deal, in excess of $100,000, was reported to include three gas stations and a Cadillac.5 However, the move created instant controversy. The National Football League’s Los Angeles Rams had signed Cannon before the game, but that did not deter Adams, who spent more than $73,000 on legal expenses to keep him from playing in the more established league.6

The signing was among the highest-profile ones in a battle between the upstart American Football League and the more prestigious National Football League. It put Adams in direct conflict with Rams general manager Pete Rozelle, who would eventually emerge as NFL commissioner, and who later would preside over the merger of the AFL and NFL. Before that merger, Adams continued to battle owners from the rival league, confidently stating, “I am going to sign all of my draft picks and any other player the other league may be after.” One reporter asserted that his “persuader” when negotiating a deal was “a stack of $100 bills as thick as a Texas steak,” yet Adams did not always come out the victor.7 He made high-profile but unsuccessful bids to dissuade Donny Anderson, Tommy Nobis, and John Brodie from signing contracts with NFL teams.8 In attempting to sign Joe Namath, Adams learned that he would not play for Houston, but that he had dreams of playing in New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles. Instead of allowing him to sign with an NFL team, Adams quietly advised the New York Jets, then owned by Sonny Werblin, to pursue the highly-touted quarterback.9

Yet if Adams offered top players lavish contracts, he would try to offset such signings with low-ball pay to most of the remaining roster. As one way to counter the cost of high-profile signings, Adams hired John Breen, a highly creative director of player personnel. Breen’s early strategy was to park himself at Love Field, a Dallas airport and a major national hub, where he would negotiate deals with recently released and likely desperate NFL players while they were between flights home.10 Before other teams were even aware that a player might be available, Breen had locked him into playing for the Houston Oilers.

The formula worked initially, as the Oilers won AFL championships in 1960 and 1961. They advanced to the AFL title game again in 1962, losing in double overtime to Lamar Hunt’s Dallas Texans before that team moved, and was rebranded the Kansas City Chiefs. But from 1963 onward, championships eluded the Oilers, with coaching instability and penny-pinching as key factors in their on-field struggles.

When it came to renegotiating player contracts, Adams played hardball. He refused to extend a raise to wide receiver Charlie Hennigan in the year the Astrodome opened, despite Hennigan’s threats to retire. Hennigan caught 101 passes in 1964, at the time a single-season pro football record, but that high-octane performance failed to get Adams to loosen his checkbook.11

Adams and Hofheinz were two headstrong Texans who battled each other, and the Astrodome served as a focal point for some of these skirmishes. When the Houston Sports Association was formed, Adams and Hofheinz both shared the vice-president title, but Hofheinz’s insider work with real-estate mogul and oil baron Bob Smith as well as his ability to gain primary control of the Astrodome project put him in a more advantageous position among Houston’s power elite.

Still, Adams made a significant splash in the newly christened American Football League. Earning AFL championships during the league’s first two seasons suggested that Adams might rise as a unique national figure in sports, though subsequent struggles tempered Adams’s potential for broader recognition. Hofheinz and Adams were creative pioneers on different fronts, yet each had egos that were not easily contained.

Adams was founder and CEO of ADA Oil Company. This successful company provided Adams with the deep financial resources to form the Houston Oilers as part of an upstart new football league that would compete directly with the much more powerful NFL. Adams teamed up with Lamar Hunt, a fellow Texan and the son of an exceedingly affluent oil baron, to spearhead the formation of the AFL. The two began laying the groundwork in 1959 for a league that would begin play in 1960 with Hunt in Dallas and Adams in Houston. The fledgling league pushed the more established NFL into a merger within a decade of starting play. Adams was a key figure in the league’s inception and its subsequent success. However, unlike the soft-spoken, even-keeled, and reflexively humble Lamar Hunt, Adams could be brash, vocal, and highly unpredictable, particularly in his early years as the owner of the Houston Oilers football team.

While founding the AFL, Hunt was sufficiently deferential to authority that even before getting the league off the ground, he naïvely approached NFL Commissioner Bert Bell to suggest that Bell preside over both leagues. However, Bell’s unexpected death in October 1959 prompted succeeding NFL officials to attempt to sabotage the new league before it took root. As plans for the AFL were unfolding, the NFL offered expansion opportunities to Hunt and Adams. Nevertheless, taking the offer would have left owners in Boston, Denver, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, and New York out in the cold, so out of a sense of loyalty Hunt rejected the offer and, to his credit, Adams did as well.

The NFL responded by extending expansion opportunities to Dallas and Minneapolis, poaching Hunt’s proposed AFL market, forcing him to unveil his new league with direct competition in Dallas while pushing him to find a new team to offset the loss of Minneapolis. Despite the blow to Hunt, the extraordinarily deep financial resources of Hunt and Adams allowed the league to move forward, with a team in Oakland added to fill the void.12

After it became clear that Hunt had lost almost a half-million dollars in the first year of operation, H.L. Hunt, his ultra-wealthy father, quipped, “At that rate, he can’t last much past the year 2135 A.D.”13 Adams, with less substantial funding, reported losing more than $700,000 in 1960.14 A broadcast contract with ABC, then the weakest of the major television networks, helped to keep the league afloat, but legendary sports producer Roone Arledge indicated that broadcasting many of these games required creative camerawork and unorthodox production techniques to mask the sparse crowds.15

The stadium situation in most AFL cities did not help matters. With the Astrodome almost five years away from construction, the Oilers began play at a facility that was described by one sportswriter as “an overused high-school field.” Jeppesen Stadium was leased from the Houston Independent School District. It was initially built in 1941 as part of a federal Works Progress Administration project, and the condition of the field was so bad that when a Houston lineman once lost a shoe during a rainy game, it was never found.16

Yet the Oilers called Jeppesen Stadium home from 1960 to 1964, and Adams was fine with the venue despite its flaws. He reportedly spent $250,000 upgrading and expanding the facility, and he did so with a specific goal in mind.17 Fearful that the NFL might try to expand to Houston, Adams appeared comfortable in Jeppesen Stadium because, according to The Sporting News, he negotiated the “sole outside playing rights in the plant, thereby shutting out the NFL.”18

Adams’s distaste for the autocratic Hofheinz likely enhanced his desire to steer clear of Colt Stadium once that venue became available in 1962. Further, his feelings about Hofheinz probably prompted a reluctance to put his team in the Astrodome in 1965. In addition, Adams’s displeasure with Hofheinz’s management style might have prompted an offer to sell the Oilers to the Houston Sports Association (HSA) in August 1962 for $2.5 million. While extending the offer, Adams asserted that he was unable to get specific information related to rental of Colt Stadium or the domed venue, which was then under construction.

In response, the HSA, then firmly controlled by Hofheinz, tersely indicated that “the HSA can’t give Adams or anyone else a firm lease agreement on the domed stadium because the HSA does not yet have one itself,” while stating that Adams, as a shareholder in the HSA, “was invited to set his own price on the rental of Colt Stadium.”19 On November 28, 1962, Adams distanced himself from Hofheinz by selling all of his HSA shares, a move that put Hofheinz and Bob Smith more firmly in control of the Astrodome and its overall operation. Of consequence, Texaco heir Craig Cullinan, one of the most influential figures in bringing major-league baseball to Houston, tendered his shares, as well.20

Despite evidence of acrimony, Hofheinz surged forward with the assumption that Adams would settle into the Astrodome shortly after it was unveiled. Although no formal agreement had been reached as the 1965 season approached, HSA publicity suggested that the Oilers would move into the Astrodome during its initial year of operation. Presumably to improve his negotiating position with Adams, Hofheinz attempted to charm Adams publicly, while citing the inadequacies his team faced before the Astrodome became available.

The HSA’s 256-page Inside the Astrodome publication lauded Adams for bringing the Bluebonnet Bowl to Houston, while praising him as “a progressive business and civic leader.” The publication also applauded Adams’s team for bringing championships to the city and for being an “attendance leader” that “became the pace setters for the rest of the circuit.” The focus on the team closed with a pointedly negative critique of Adams’s prior venues, something that likely would not have occurred if the Oilers had played in Colt Stadium. According to the publication, “The Oilers can look back on five years of living through inadequate seating and parking as time well spent, and look forward to years of fruitful living in the sports showcase of the world, situated in the football hotbed of the nation.”21

Hofheinz’s public-relations tactics did not work. Those carefully studying the Houston negotiations in 1965 struggled to explain why Adams, after being slated to put his team in the Astrodome, abruptly signed a deal with Rice University instead. The Sporting News editor, C.C. Johnson Spink, pointedly suggested that Hofheinz might have set exceedingly high rental terms “to force the Oilers out and clear the way for a National Football League club, possibly one in which the Judge might own an interest.” To support such speculation, Spink indicated that rent for Adams was reported to be “the highest any pro football team has ever been asked to meet … without any exclusive rights against an NFL team coming in at any time.” Spink further asserted that Adams’s sudden shift might have unfolded when an influential Rice University board member “who has little affection for Hofheinz thought this an excellent opportunity to stick a harpoon in the Judge’s hide.”22

In retracing the Oilers’ early years, The Sporting News columnist Wells Twombly joked that the conventional wisdom from insiders was that “Rice Stadium would be open to professionals at about the same time the Baptists were permitted to hold prayer sessions on the high altar at St. Peter’s in Rome.”23 Hofheinz likely felt as though Adams was severely constrained in his options. Even though his relationship with the Oilers’ owner may have been icy, Hofheinz may have been convinced that the Astrodome provided Houston’s fans with such a high-profile, premium venue that it could be prudently leveraged by the Oilers’ owner to obtain some degree of profitability.

Adams, however, appeared to regard the high rental fees as an irretrievable expense and at the same time he seemed distrustful of Hofheinz. After a negotiation process in which Adams submitted his desired contract terms to Hofheinz, who then modified them and simply returned the document with an expectation of a signature, the Oilers owner decided that his preference was to continue showcasing his team in a less opulent and less costly venue.

In response, Hofheinz did what Spink speculated he would do. He tried to lure an NFL team, inviting Commissioner Pete Rozelle, an earlier nemesis of Adams, to visit the Astrodome. When it became clear that the NFL would not permit Hofheinz to hold a controlling interest in baseball and football teams simultaneously, he tried to coax Houston native and millionaire oil baron John Mecom into an ownership position to put a professional football tenant into the Astrodome. The NFL instead granted Mecom an expansion opportunity in New Orleans, where the team began play, like Adams, in an outdoor venue beginning in 1967. Mecom’s team, the Saints, eventually moved into the Superdome, a huge indoor structure that was inspired by the Astrodome.24

After three years of competition away from the Astrodome, Adams finally relented, stating that “playing in the Rice Stadium rains cut crowds, so I looked forward to getting in the Dome.” The Oilers became the first professional football team to play its home games indoors. Despite his frustration, Adams offered effusive praise for Hofheinz once a deal was hammered out, stating that “the people of Houston really got a bargain” with the Astrodome, while indicating, “I have the highest respect for Judge Hofheinz and what he has done for the city.” Despite asserting that negotiations were “amicable,” Adams admitted that he had the final stages of the process handled entirely by intermediaries, making it abundantly clear that his preference was to avoid direct negotiations with Hofheinz.25

The Oilers struggled in their early years at the Astrodome, but by the close of the 1970s, they had built an exciting, hard-hitting team directed by Texas native Bum Phillips. They advanced to the conference championship game in 1978 and 1979, but after they fell short in the playoffs again in 1980, Adams fired the popular Phillips. By the late 1970s, Roy Hofheinz was no longer involved with the Astrodome, but Adams’s team was still locked into the venue as his home base.

Bothered that the Astrodome was no longer a premium venue, Adams in 1987 threatened to move his team to Jacksonville, Florida, if action was not taken to improve the Dome. He insisted on added seating and major renovations. He also pushed for a cap on his annual rent payments and fought for a more substantial share of advertising, parking, and concessions revenues, including a demand that would have given Adams as much as 83 percent of the parking revenues. The Houston Sports Association attempted to negotiate with him.26 In addition, Harris County approved $50 million to expand and renovate the Astrodome, a figure that later ballooned to $67 million.27

Although Hofheinz died in 1982, the renovations eliminated some of the stadium infrastructure that the late judge most coveted. The luxury apartment that once served as home base to the Hofheinz empire was dismantled and most of its contents discarded, as were the massive scoreboard, the bowling alley, and several other well-publicized amenities. The all-faiths chapel was also removed; most of its contents were donated to a local hospital.28

The Astrodome, touted for all its luxuries and amenities, ultimately proved to be too restrictive to Adams, whose desire for a higher percentage of stadium-based revenue could not be satisfied as long as the Houston Astros’ hierarchy controlled the venue. By the 1990s the dynamic in NFL team ownership had changed. New stadiums were being built and owners, who were compelled to share a portion of their gate revenues, were getting better lease terms than in a generation prior. Of significance, owners were not required to share skybox, advertising, parking, and other stadium-based revenue streams with competing owners. Publicly financed stadiums had become a cash cow for owners more than in any previous era.29 Football historian Michael Oriard aptly noted, “Television continued to be the largest single pot of money … but stadiums became the new economic engine driving the NFL into the financial stratosphere.”30 Adams pushed harder to gain profits that several other owners were now obtaining, aggressively attempting to grab his piece of the lucrative stadium-generated pie.

Renovations made in the 1980s pacified Adams temporarily, but he decided that the Astrodome could no longer serve his team looking forward. Thus, by the 1990s he pushed hard to get a brand-new domed stadium built for his team. Mayor Bob Lanier pushed back, citing city services as a more important priority for Houstonians, though talk of funding an open-air stadium unfolded. The popular mayor attempted to negotiate with Adams, but he was hard-nosed about protecting taxpayers. He pointedly said, “It’s very hard for me to go into neighborhoods that need streetlights and sidewalks and police and parks and ask those people for money for a stadium they probably can’t afford to buy tickets for.”31

In response, Adams predictably threatened to move, and eventually carried out the threat, shifting his franchise to Tennessee, where he played in outdoor venues but on terms that he was in a better position to dictate. Adams was reviled by many of Houston’s diehard football fans, but he did not move from the Houston area even after his team shifted elsewhere.

The Oilers departed after the 1996 season, a year before their Astrodome lease officially ended, and they were later renamed the Tennessee Titans. Initially, Adams expressed a willingness to stay in Houston until his Astrodome lease fully expired, but once his announced move was made, Houstonians reacted with revulsion, with many avoiding the stadium on game day. With numerous empty seats as the new reality, the NFL was glad to approve the team’s departure a year earlier than expected. Houston officials hammered out a settlement that cost Adams more than $5 million, but it allowed the team to relocate immediately.32

Nevertheless, the football team that cost Adams $25,000 in league fees in 1959 was valued at $1.06 billion when he died in October 2013.33 Clearly, Adams’s pioneering entry into professional football was a major financial success, yet the hard-charging oil baron struggled for respectability and acceptance during his time in Houston. Stadium-related issues were often at the core of that struggle. When the Astrodome opened in 1965, Adams resisted playing in the highly touted venue. Somewhat fittingly, when his team left Houston, it was in large part because the revolutionary Astrodome failed to meet his expectations.

ROBERT C. TRUMPBOUR is associate professor of communications at Penn State Altoona. He is the author of The Eighth Wonder of the World: The Life of Houston’s Iconic Astrodome (Nebraska University Press) and The New Cathedrals: Politics and Media in the History of Stadium Construction (Syracuse University Press). He has taught at Pennsylvania State University, Southern Illinois University, Saint Francis University, and Western Illinois University. Prior to teaching, Trumpbour worked in various capacities at CBS for the television and radio networks.

Notes

1 Edgar Ray, The Grand Huckster: Houston’s Judge Roy Hofheinz – Genius of the Astrodome (Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1980).

2 Harry Shattuck, “Money, Intrigue, Suspense – Oilers vs. HSA Battle Heats Up,” Houston Chronicle, September 13, 1987: Sports, 1.

3 Robert Lipsyte, “Astrodome Opulent, Even for Texas,” New York Times, April 8, 1965: 50.

4 Ed Fowler, Loser Takes All: Bud Adams, Bad Football, and Big Business (Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 1997), 33.

5 “Cannon Scores After Game – Signs 100G Houston Pact,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1960: 22.

6 “Oilers Spent $73,000 in Court Costs,” The Sporting News, December 3, 1966: 9.

7 Joe King, “College Heroes Eye Adams’ Money Tree,” The Sporting News, January 5, 1963: section 2, 1.

8 Jack Gallagher, “New Trend in AFL: Every Team Seeks Lincoln-Style Back,” The Sporting News, December 4, 1965: 54; Al Thomy, “Nobis, NFL Rookie of the Year, Bargain at Any Price,” The Sporting News, January 7, 1967: 5; Joe King, “Interloop Jumps Possible, but None Did,” The Sporting News, February 11, 1967: 9.

9 John McClain, “Remembering Bud Adams – Pioneering Owner Part of a Colorful Era,” Houston Chronicle, October 22, 2013: Sports, 1.

10 Al Carter, “See Ya, Blue: Oilers Leave Legacy of Odd Deals, Bad Luck, and Low-Budget Absurdity,” Dallas Morning News, June 29, 1997: 22B.

11 Ibid.

12 Michael Oriard, Brand NFL: Making and Selling America’s Favorite Sport (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 19.

13 Ed Gruver, The American Football League: A Year-by-Year History, 1960-1969 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1997), 56.

14 Clark Nealon, “Colt Owners Shun Chance to Buy Oilers,” The Sporting News, September 1, 1962: 20.

15 Roone Arledge, Roone: A Memoir (New York: Harper Collins, 2003), 64.

16 John Lopez, “Remembering the 1960-61 Oilers – Days of Glory,” Houston Chronicle, December 15, 1991: Sports, 17.

17 Clark Nealon, “Vets Spark Oilers to Fast Start in AFL,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1960: 23.

18 Joe King, “New League Hurls Challenge at NFL – Drafts Name Stars,” The Sporting News, December 2, 1959: 46.

19 Nealon, “Colt Owners.”

20 “Seven Houston Shareholders Sell Their Interest in Club,” The Sporting News, December 8, 1962: 21.

21 Inside the Astrodome: Eighth Wonder of the World (Houston: Houston Sports Association, 1965), 208.

22 C.C. Johnson Spink, “We Believe,” The Sporting News, June 19, 1965: 14.

23 Wells Twombly, “Ridiculous Business Starting Again,” The Sporting News, February 16, 1976: 8.

24 Ray, 332.

25 Ray, 332-333.

26 Harry Shattuck, “Adams Details Beefs with HSA,” Houston Chronicle, October 10, 1987: 14.

27 Bill Coulter, “$50 Million Upgrading for Dome Approved,” Houston Chronicle, July 22, 1987: A1. For final expense totals for the Astrodome renovation, see Fowler, 152.

28 Brenda Sapino, “Hofheinz’s Dome Rooms Are Doomed,” Houston Chronicle, May 5, 1988: A1.

29 Robert Trumpbour, The New Cathedrals: Politics and Media in the History of Stadium Construction (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2007), 277-278.

30 Oriard, 153.

31 Fowler, 157.

32 Steve Brewer, “Tennessee-Saw Battle Officially Over for Oilers,” Houston Chronicle, July 4, 1997: A1.

33 David Barron, “Bud Adams: 1923-2013 – He Brought Us the Oilers, Then Took Them Away,” Houston Chronicle, October 22, 2013: A1.