Early Baseball in Washington, DC: How the Washington Nationals Helped Develop America’s Game

This article was written by Carol McMains - Frank Ceresi

This article was published in 2005 Baseball Research Journal

Baseball’s Birth

By 1840 changes were occurring swiftly as the country’s new industrialism began to take hold and country life, so dependent on large areas of land, began to give way to crowded city life. New forms of leisure and recreation were needed as field sports and informal schoolyard games were becoming less available to workers in towns and cities. It was within this context that baseball, as we know it today, began as a game to be reckoned with.

The first real turning point in the development of baseball occurred in 1842 in the biggest, most bustling city of them all, New York City. A group of middle- and upper-class gentlemen in Manhattan met to play regularly scheduled games of baseball against each other “for health and recreation.”1 They formed a club and called themselves the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York. Today, the Knickerbockers are universally regarded as the nation’s first organized baseball club. They regularly met after work, generally around mid afternoon, to enjoy each other’s company and the game that they found exhilarating.

Three years later, after losing their practice field in Manhattan, the club journeyed by ferry to Hoboken, New Jersey, to seek new grounds. There they played and practiced base ball on the Elysian Fields overlooking the Hudson River.2 It was during this time that a serious young Knickerbocker, Alexander Cartwright, suggested to the others that the team become more organized. On September 23, 1845, approximately 30 members of the club convened at McCarthy’s Hotel in Hoboken. At this meeting the idea of formalizing new rules was put forth. The rules, forever known as the “New York” rules, were drawn up and codified, and the seeds of something big were sown.

Although other areas of the Northeast sprouted ball clubs of one form or another, organized competitive baseball was pretty much confined to New York City and its immediate suburbs. Even though ”baseball momentum” clearly emerged from the valiant efforts of the Knickerbockers and their crosstown rivals, the Gothams, history tells us that in New York City the most popular outdoor team bat and ball sport of the late 1850s was not baseball but cricket. After all, it was little more than 75 years before that this young country had split from England, and old habits died hard. Even in Hoboken, right on Elysian Fields, the “home” grounds of the Knickerbockers, a crowd of 24,000 men and women gathered in 1859 to watch their favorite players in a cricket match.3 That kind of crowd dwarfed the number of spectators attending baseball matches in the 1850s. That, however, was about to change. Within the next decade baseball would become far more popular than Alexander Cartwright, his Knickerbocker teammates, or anyone else could have possibly imagined.

The Baseball Explosion Begins: Here Come the Nationals

During this time interest in baseball began to stir in Washington, D.C., the nation’s capital, a city on the verge of being swept into the great Civil War. It began innocently enough when a group of mostly federal government employees took a cue from their counterparts up north and formed an organized baseball team. It would be known as the Washington Nationals, a team that would be significant to the development of the national pastime.

That the men were civil servants gave the group an air of respectability, for government workers of that era were a considerable force in the social and economic life of the city. The group, though certainly not wealthy, was comprised of upper-middle-class workers who were envied for their guaranteed wage and job security. Accounts of the day report that many were “thrilled” by the prospect of deserting taverns and the Willard and Ebbitt Hotel bars for the :wholesome, invigorating outdoors.” Quickly, and with a determination that would make any governmental bureaucrat proud, the officers undertook the task of writing rules for their club,5 the Washington Nationals Base Ball Club. They elected James Morrow, a clerk from the Pension Office. as president, and Joseph L. Wright, the Official Doorkeeper of the United States House of Representatives, as vice president. Arthur Pue Gorman, the 22-year-old chosen as secretary, also worked on Capitol Hill. He later made his mark, becoming a reliable player for the Nationals, an organizer who helped hatch the team’s “grand tour of the west” directly after the Civil War, and a longtime United States senator from Maryland.

Because of the recent find of baseball documents in the French Collection, we are able to peek inside the team’s rule book and get a flavor of the game as it existed at the time of the Civil War.6 The book tells us that baseball, when the Nationals first formed, was clearly an amateur sport. Not only were there no salaried players, but membership on the Nationals required dues to be paid by the players to the club, initially of 50 cents and 25 cents each month thereafter. Second, the membership was exclusive. Article I of the Constitution declared that the club would have no more than 40 members, and “gentlemen wishing to become members may be proposed” and thereafter would be “balloted for.” Article II set up a “committee of inquiry” and membership would be denied by “three black balls.”

The rules within the Constitution’s Bylaws set forth a stringent code of conduct for the ballplayers. The club wanted the men on the field of play to be exemplary and polite. This was clearly thought to be a way to weed out riffraff and gamblers who frequented horse races and boxing matches.7 Article II of the Bylaws admonished that a fine of 10 cents would be levied at any member who used “improper or profane language.” It didn’t stop there! If you, as a member of the Nationals, “disputed an umpire’s call” you “shall” be fined a quarter. Worse yet, if you “audibly expressed [your] opinion on a doubtful play before the decision of an umpire,” you would be a dime poorer. Anyone “refusing obedience to a team captain” would be fined 10 cents.

Other rules are not quite as quaint when viewed through the lens of contemporary life, but they certainly illustrate the game as it was played.Though baseballs were specific as to size and weight, they were harder and smaller than what is used today. Also, wood bats were limited in dimension, but they were larger and longer than those commonly used in the modern game. Baseball in 1860 was definitely a hitter’s (called the “striker”) game. Article III, Rule 6 of the Bylaws nails that point. It specifies that the ball must be “pitched,” not “jerked or thrown” to the striker. The rule directed the pitcher to heave the ball, in a discus-like motion, toward the striker. As was the baseball custom of the day, the striker could tell the pitcher exactly where to place the ball. If the pitcher didn’t “pitch” the ball to the striker’s liking, but instead “threw or jerked” it in a confusing manner, the umpire could call out a warning, “Ball to the bat!” and walk the striker after only three called balls.8

On July 2, 1860, the Washington Star recorded the first box score for teams representing the District of Columbia.9 Art Gorman scored six runs and Mr. French added five of his own, as the Nationals beat the Washington Potomacs Ball Club. The Potomacs, likely filled with other men with government-related jobs, did not have the staying power of the Nationals, and any reference to ”the Potomacs” shortly disappeared from local papers. They apparently were not that great, either, as the Potomacs got trounced, 46-14, by the stronger Nationals club in Washington’s historic first recorded game.10

The Civil War Years

Washington, D.C., was, of course, in the “eye of the hurricane” during the Civil War years. For citizens of the District of Columbia, those were tense and trying times because not only was the city the focal point and symbol for a unified nation, but it was very precariously situated. After all, Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, was less than a 100 miles south of the District line. Yet, through it all, baseball in Washington, as in many parts of the Northeast, did not halt. The game actually flourished.

One of the reasons that baseball prospered during the war was, unlike many other sporting and recreational games, it was portable: it could be played in any relatively open field. All you needed was a bat or large stick, a ball, at least some knowledge of the rules of the game, and willing participants. Unlike cricket, you did not need nicely manicured grass. For the soldier on the field whose days were spent either drilling or being terrified that they might soon be engaged in combat, the game was a welcome relief. In short, not only did it lend itself to the feeling of being part of a team, a nice feature in a military setting, but also it was fun. One soldier from Virginia in 1862 said it best when he wrote:

It is astonishing how indifferent a person can become to danger … The report of musketry is heard a little distance from us … yet over there on the other side of the road is most of our company playing Bat Ball and perhaps in less than a half an hour they may be called to play a ball game of a more serious nature.11

In the meantime, the Washington Nationals were doing their part to keep the game going during the Civil War. Although the Potomacs disbanded, the Nationals kept playing whenever and wherever possible. One of the Nationals’ biggest games of 1861 was played on July 2 against the 71st New York Regiment. The team of New Yorkers was well schooled in the intricacies of the game, and their superiority on the field showed as they won 41-13.12 That game would be, however, the New Yorkers’ last bit of frivolity, for that regiment was on its way to Manassas, Virginia. Within a few short days the 71st would be surprised by the strength of the Confederate Army, and the regiment sustained heavy losses 1n the Battle of Bull Run.13

For the next two years, most of the Nationals’ games were played locally. All of the ball clubs in the Washington area that sprouted up during this time sported names that perfectly captured the tenor of the times and Washington’s prominence as the capital city – the Nationals, Unions, and Jeffersons. After all, this was a period of intense patriotism in the city that housed the federal government during the time when the outcome of the Civil War was far from certain. The Nationals played both of the other District teams, winning every time.14 For the first game of the 1862 season, on May 20, the Nationals welcomed the newly formed “Jeffersons” into the baseball community by tattooing them, 62-22. Ned Hibbs of the Nationals socked five home runs in that game, future senator Gorman hit three, and Mr. French tallied nine runs. The game was covered in a local newspaper, and the following telling line was recorded: “The spectators of the game were numerous and cheered bravely whenever a home run or fine catch was made.”

In August 1862 the Nationals again played against New York’s 71st Regiment in Tenleytown, Maryland (now part of the District of Columbia). This time, however, the result of the rematch game would be different, as the Nationals were victorious 28-13. At first glance the final score indicates that the Nationals were becoming more talented on the field, although the New York 71st manpower was, by then, depleted due to the war. The box score and roster of the game, the only one known to exist, is neatly handwritten in the French Collection materials, presumably by French himself.15

By midseason the following year, the Nationals kept playing despite the increased volatility of life in the nation’s capital. In July 1863, as the Battle of Gettysburg raged north of the city in Pennsylvania, the Nationals played ball and were drawing crowds wherever they went. They won all games they played against the Jeffersons, the Unions, and a new Baltimore club, the Pastimes.

Members of the Nationals team were gaining stature outside of the baseball diamond as well. Crafty second baseman Arthur Gorman, newly elected as the team president, was named the Postmaster of the Senate.16 His climb up the political ladder would in time benefit the team greatly. Others who played, or who would play, for the Nationals saw significant combat action during the war. One such ballplayer, Seymour Studley, was not only wounded but almost died of heat stroke while fighting for the Union.

The Nationals continued to test their skills against Union soldiers until the very end of the war. For example, on May 17, 1865, the team battled the 133rd Regiment of New York in a game played at Fort Meigs in Maryland as the Union troops were mustering out of the military. What is most interesting about that particular game is the almost genteel tone of the game summary that appeared in the unidentified newspaper clipping found in the French Collection. Its substance is very revealing especially when the reader considers the light mood that must have pervaded the soldiers as well as the civilians on the Nationals ball club, for this game took place barely six weeks after General Lee surrendered to General Grant at Appomattox.

It was reported, “Each and all of the nines [the starting lineup] played in first class style endeavoring to make it an interesting and agreeable match.” Further, the men apparently worked up a nice appetite, as the paper reported, matter-of-factly, “During the progress of the game a handsome collation [light meal] was spread and the urbanity of the officers and members of the 133rd added much to the entertainment!”17

Hungry or not, 1865 was quite a year, as the Nationals ballplayers kept winning. The Civil War had ended and Washingtonians were ready to celebrate. Baseball helped fill that void and the game’s popularity was cemented in the capital city forever. Nice-sized crowds, from several hundred into the thousands, saw the team take on and beat all comers, from the Baltimore Pastimes and that city’s newly formed Enterprise Club to the Nationals’ old rivals, the Washington Unions. On August 22, 1865, the Nationals beat the Jeffersons in what the newspapers dubbed the “Great Baseball Match for the Championship of the South.”

This might have been a bit of local hyperbole, probably induced by their newly elected president, the clever and politically connected Postmaster Gorman. However, the Nationals did win the “championship” game, 34-14, and within a couple of days two of the “better” Northern teams accepted an invitation from Mr. Gorman himself to play the “champs” in a “baseball tournament” in the capital city.18

Baseball and High Society in the Nation’s Capital

The teams that Mr. Gorman invited to the tournament were the two most powerful baseball clubs in the country during the 1865 season. The Atlantics from Brooklyn, New York, were undefeated, winning all 18 of their games.19 That team featured the very popular Dickey Pearce, a great shortstop who some credit with having invented the bunt.20 The Philadelphia Athletics were no slouches, either. They won all except three of their games for the year and showcased the talented and influential Albert Reach,21 who later made a fortune manufacturing baseball equipment.22

With this impressive talent on its way down from the north, the wily Mr. Gorman knew what to do to put the Nationals on the front pages. A newspaper story dated August 28 tells the tale.23 Arthur Gorman met the ball clubs at the train station in Washington in what turned out to be a very significant three-day stay. Gorman rolled out the red carpet in a serious way. He led the visiting ball clubs by four horse coaches draped with American flags for a special tour of the United States Capitol and followed by taking his visitors to the White House. Though the players missed President Andrew Johnson, they met him the following day at the presidential home. This was the very first time a sports team would be received by the President of the United States.

After the White House visit, the guests went to their rooms at the Willard Hotel, and then joined the Nationals at the “Presidential Grounds” to play baseball.24 The game might have been interesting, but the show was really in the stands. What stands, say you? It seems that Mr. Gorman was able to not only arrange the team’s presidential visit, but he made sure that spectator seats were erected on the Presidential Grounds where the gentlemen or the government, including Cabinet-level appointees, escorted their ”belles of the capital” in their finery to watch the contest.25

Not only that, but the fans had the privilege of actually paying a hefty one dollar charge to enter the grounds to watch the affair. Even though the Philadelphians, and next day the New Yorkers, won both games, 5,000 of Washington’s elite witnessed more than a pair of baseball games – they witnessed a tournament turned into a social event at a most opportune time. The gala atmosphere was just what the war-weary city, indeed the nation, really needed. The game of baseball, almost as a backdrop, had now really come into its own. Also, the “battle” for sports supremacy was now over and baseball was the victor. As the American Chronicle of Sports and Pastimes stated in 1868, baseball had changed more in 10 years than cricket had in 400 – because it adapted to the American circumstances.26

For the next year and a half, the Nationals capitalized on their popularity in the Washington region and continued to battle clubs from other areas of the country as well. The Nationals again played a New York team on October 9, 1865, the excellent Excelsiors Club from Brooklyn, beating them in a “close” game, 36-30. This entitled the club to the prestigious “trophy ball.”27 They also continued a tradition that was becoming standard for major ball clubs of the day. Since the game was played on their “home field,” the boys hosted a magnificent feast for their guests after the game, with rounds of toasts, speeches, and general all-around merriment.28

During 1866 the club was sharpening their collective skills in preparation for what would be their grand “tour of the west” a year later, a tour that would forever confirm the influence of the Washington Nationals over the game of baseball. During the summer they won every game they played against the other local baseball clubs, the Jeffersons and the Unions.29 After they dispensed with the local talent, the team traveled south into the former Confederacy to play and beat the Monticellos from Charlottesville, 37-7. They topped off the mini tour and traveled east to crush the Unions of Richmond, 143-11. They were now ready to head north to make good on their promise the previous year to visit the clubs from New York that had come to Washington in 1865.

Reality set in during that trip. The Nationals’ only defeats in 1866 came in New York City, still the hotbed of organized baseball, where the most talented players in the country resided. As much of a mark as the Nationals had made in the capital region, New York was still the baseball capital. In fact, the New York-based National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) was at its height as an organization. The Association saw its membership numbers rise dramatically during the first full year after the Civil War ended. Arthur Pue Gorman officially left the Washington Nationals as a player and officer to become president of that Association. Gorman was, after all, an ambitious man, and the presidency of the only organized baseball association was prestigious. However, Gorman would be perfectly positioned to shortly help guide his old team, but from behind the scenes, in what would become the team’s finest moment.

The Nationals took on baseball’s “best of the best” during the 1866 trip, including the nation’s strongest club during that season, the Unions from Morrisania, New York. But they simply could not get over the top. They lost to the Unions twice as well as to New York City’s excellent Excelsior and Gotham ball clubs.30 By the end of the year, the Nationals would claim dominance in the Washington area, as they were even dubbed “champions of the south,” and they clearly were considered peerless and polite hosts when the New York boys visited town for a friendly game on the Nationals’ home turf.31 However, the 1866 trip “up north” revealed that the Washington team needed to strengthen itself if they were to make their mark on the national stage.

The Nationals’ Great 1867 Tour of the West

Certainly 1867 was the banner year for the Washington Nationals. The need for shaking things up fell into the capable hands of the club’s new president. the former Union officer Colonel Frank Jones. The Colonel had found employment at the Treasury Department after the war. That department, Washington’s largest, was an easy walk to many a baseball game in and around the National Mall, as baseball contests dotted the landscape by the war’s end. Although Art Gorman’s time was cramped due to his political and NABBP responsibilities, he was still able to offer Jones advice and political goodwill. The men struck upon an idea that they felt certain had merit.

Why not take the Nationals on the road into America’s heartland to showcase the game they loved? Although baseball clubs had previously traveled up and down the Northeast for years, said “tours” were really very limited and confined to the Northeast and the capital city’s immediate south. The Washington pair correctly thought that a “grand tour of the west,” a first for any baseball club, would really put their team on the map, help spread the baseball gospel, and ultimately cement the Washington Nationals’ rightful place in history.32 They would be right.

From the Nationals’ New York travels in 1866, they were well aware of the fine play demonstrated by a 20-year-old, George Wright, who played for the nation’s top team, the Unions from Morrisania. Young Mr. Wright not only played for the team that thrashed the Nationals, 22-8, but he also came from impressive baseball stock. He was the son of a renowned cricketer and younger brother of Harry, whose baseball roots went back all the way to the great Knickerbocker teams of the late 1850s. Perhaps it was a promised job as a clerk at the Treasury Department that did the trick – after all, a steady paycheck was a nice thing to have – or it could have been Colonel Jones’s evocative talk of taking his team “on a grand tour of the west,” a first for any organized club. Either way, Wright was approached and agreed in April to play with the Nationals for the 1867 season.33

The Nationals followed their Wright score by quickly landing two other New Yorkers, catcher Frank Norton, a whiz with his barehanded grabs, and the impressive first baseman George Fletcher from the same Brooklyn Excelsior club that edged Washington, 32-28, the previous year. Norton had led the Excelsiors with 70 runs in 20 recorded games during the 1866 season, and Fletcher came in second for the club with 62 runs.34 Shortstop Ed Smith, formerly of the Brooklyn Stars, Harry McLean, who at one time played with the Harlem Club, and from the Brooklyn Eckfords, the talented George H. Fox rounded out the New York contingent. The boys from the north were joined by the veteran Washington Nationals players; Will Williams, an excellent pitcher who was also a law student at Georgetown University; Henry Parker of the Internal Revenue Service, fleet outfielder; and Civil War veterans Harry Berthrong and Seymour Studley. Both Berthrong and Studley worked at the Treasury, Henry at the Office of the Comptroller and Seymour as a clerk.35

Excitement was in the air as the fully assembled team began the 20-day, 10-stop western tour by railway on July 11, 1867. It would be covered not only by the Washington Star, but also by the influential and important weekly journal known as The Ball Players Chronicle. The man credited with being the nation’s first daily baseball journalist, Henry Chadwick, also traveled with the team to cover the games. Not only did “Father Henry,” as he was affectionately known, write the content and edit The Ball Players Chronicle and contribute columns to assure Star coverage, but he also provided up-to-the-minute details of the tour to other traveling journalists from the New York Times, New York Mercury, and New York Clipper.36 The result would be that the Nationals’ tour received press coverage that far exceeded anything ever done in sports before. Colonel Jones and Art Gorman, who would join the team in Chicago, were ecstatic!

The first game of the tour was played against the Capitals of Columbus, Ohio. Let’s let Mr. Chadwick set the stage:

The arrangements for the match were excellent, a roped boundary enclosing the field, and all the base lines laid down properly. Tables were provided for the scorers and members of the press, seats for the players, with a retiring tent, and also seats for ladies. A cordon of carriages, mostly filled with the fair belles of Columbus, occupied two-thirds of the outer portion of the field, and the surroundings of the grounds with the white uniform of the Columbus players – the flags and the assemblage, altogether made up a very picturesque scene indeed. Though it was but ten o’clock in the morning, an hour when hundreds who desired to witness the game could not well get away, quite a numerous assemblage of spectators were present, the delegation of ladies being very numerous, something we are glad to record.37

The game showed the team, and the throngs of spectators who watched, just how powerful the Nationals were. The Capitals scored the first two runs of the game, but things quickly got out of hand for the host team. Each of the Nationals scored at least seven runs, as they walloped the Columbus Capitals, 90-10. At that point the game was called after an abbreviated seven innings, the dinner bell rang, and the teams went on to enjoy the post-game feast, a routine that would occur in virtually each city on the 10-stop tour. It was, as Chadwick duly noted, a “pleasant and rational opening” for the Nationals’ tour.38

It was thought that things would be a bit tougher for Washington the next day in Cincinnati for their game against the Red Stockings. After all, this team featured Harry Wright, George’s older brother and an old hand from the Knickerbocker days of yore. The locals were impressed with the Nationals’ blue pants, white woolen shirts, and blue caps and cheered the team’s arrival. But the home team had little to cheer about as Washington, led by the younger of the Wright brothers, thrashed the Red Stockings, 53-10.39 The Nationals played again in Cincinnati the next day and spanked the Red Stockings’ crosstown rivals, the Buckeyes, 88-12.

Things continued in favor of the touring Nationals for the next several stops. George Wright and George Fletcher each hit three homers on their way to an 82-12 victory over Louisville. The next day, George Wright bashed five homers to lead the team over Indianapolis. Fletcher hit only three homers, but the others began to flex their collective muscle. The final score? 106-21! After two days during which the team crossed the Mississippi by steamboat, the Nationals downed the Unions from St. Louis, in scorching heat of up to 104 degrees, 113-26. That very afternoon, in the same sweltering heat, they played in the same city again. This time it was closer, but the Empires could barely hang on as the Washington club bested them, 53-26.

This was to be the beginning of the final leg on the tour, as the train took the players to Chicago for the last three games. The boys were tired from the trip and those hot days in St. Louis but soon, it was thought, they would be heading back in triumph to the nation’s capital. By any measure, the tour was far more successful than even Colonel Jones or Art Gorman could have possibly imagined. Crowds from all over the Midwest met the players at every stop. They were wined and dined in each city, even those where they annihilated the hometown ball club. Handsome George Wright, slugger George Fletcher, pitcher Will Williams, and the others had their own flock of fans to contend with, both male and female.40

Thanks to the omnipresent pen of Henry Chadwick, and other journalists who were now reporting in their own newspapers as each game unfolded, each Nationals game, and the exploits of the individual players, were followed in every major city. The baseball gospel was indeed spreading!

When the team arrived in Chicago, they were met by hundreds of fans as well as the ballplayers of all three of the Chicago-area teams they were to play, the rival Atlantic and Excelsior squads and the much less experienced Forest City Club from Rockford, Illinois. The latter club had traveled 100 miles from their home to “host” the Nationals for the first game. It was to be a tune-up for the stronger Excelsior and Atlantic clubs that hailed from Chicago proper.41

However, things did not go as everyone predicted. The long tour, the July heat, and the hoopla finally caught up with the Nationals. The Forest City Club, led by 16-year-old pitching sensation Albert Spalding, jumped to an early lead in a game that was marred by two rain delays.42 The “corn crackers” from Rockford never relinquished their lead.43 The final score was 29-23. That was the only loss the Nationals sustained during the entire tour.

The Nationals’ defeat, however, only heightened an already enthusiastic fan base for the remaining two games. After all, the home team newspapers blared, if the less experienced Forest City Club could win, think of what the two major big city clubs could do! Not much, it seems, for the Nationals, having been able to rest for a day, came roaring back. In front of a crowd that was estimated to be 8,000 strong, they first annihilated the Excelsiors, 49-4, and finished their tour taking apart the Chicago Atlantics, 78-17.44

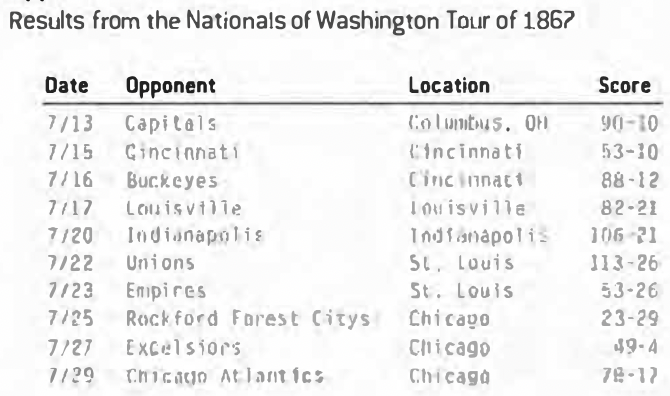

The boys really ended on a high note. The team had traveled to parts of the country that had never really seen the evolving game played so “splendidly,” they had won nine of ten games, and they outscored their opponents 735 to 146 [see Appendix]!45

The Nationals’ Legacy

By the end of the decade that defined baseball’s explosion, the Washington Nationals’ fingerprints were everywhere. Their influence would be felt locally and nationally. For a baseball club that began less than a year before 1860, it is amazing what the team accomplished in such a short period of time. Not only did the Nationals help keep the game alive during the Civil War by hosting ball games with visiting Union soldiers, but by 1865, as the war ended, at a critical time when the weary country needed a shot in the arm, the team for the first time was able to meld the excitement of the national pastime into an exuberant patriotic celebration that involved even the President of the United States.46 Additionally, their baseball dominance locally sowed seeds of the game within the entire city, and those seeds helped sprout not only significant white teams but African American teams as well.47

Last, the Nationals will forever be known for their groundbreaking “grand tour of the west,” where they introduced to scores of people the game that would quickly be recognized as our country’s national game. Forty years after the tour, the then “grand old man” of baseball, Henry Chadwick, made that point many times, and even the influential Spalding’s Baseball Guide credits the Nationals for “opening the eyes of the people” to the beauty of the game and the tour for serving “to intensify the passion for the game by stimulating the formation of clubs that wanted to achieve similar renown.”48

Appendix

Notes

1. Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, Baseball. An Illustrated History [New York: Knopf, 1994), 4.

2. What we now call baseball was originally referred to as two words, base ball. By the end of the Civil War, most references are to the word “baseball” as we know it today.

3. Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 14.

4. Shirley Povich, The Washington Senators [New York: G.P Putnam’s Sons, 1954], 1.

5. That the met would form a “gentleman’s society” to play baseball in 1859 was hardly surprising. During the 1840s and ’50s, a whole host of societies and associations sprang forth. Political groups and trade unions were formed. Likeminded folks banded together to form everything from anti-slavery societies to the Ancient Order of Hibernians and B’nai B’rith. Things went so far that one poor soul lamented, “A peaceful man can hardly venture to eat or drink, or go to bed or get up, to correct his children or kiss his wife without obtaining the permission or direction of some … society.” Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 13.

6. The materials in the French Collection were donated to the Historical Society of Washington, DC, by Miller Young in 1999. The documents and memorabilia were part of the estate of Nicholas Young, a founder of the Olympic Base Ball Club in Washington, DC in 1866.

7. In fact, Rule 30 of the Bylaws forbade betting. French Collection, HSWDC, 17.

8. Stephen D. Guschov,The Red Stockings of Cincinnati: Base Ball’s First All-Professional Team and Its Historic 1869 and 18?0 Seasons (Jefferson, NC, and London: Mcfarland, 1998), 39. The appearance of the curveball in 1868, years after the Nationals first wrote their rules, obviously caused quite a stir. When the “secret pitch” was unleashed by one William “Candy” Cummings as his New York club played Harvard University’s top team, Charles W. Eliot, President of Harvard, said with disdain, “I am instructed that the purpose of the curve ball is to deliberately deceive the batter. Harvard is not in the business of teaching deception.” Ward and Burns, Baseball: An Illustrated History, 20.

9. Morris A. Bealle, The Washington Senators: The Story of an Incurable Fandom (Washington: Columbia, 1947), 8.

10. Exaggerated scores were not uncommon during the early years of baseball. Some teams were simply more skilled than others.

11. Ward and Burns, Baseball: An Illustrated History, 32.

12. Confirmed by handwritten notes likely written by Mr. French himself. French Collection, HSWDC, 43.

13. Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 41.

14. Bealle, The Washington Senators, 9.

15. French Collection, HSWDC, 48.

16. Bealle, The Washington Senators, 9.

17. French Collection, HSWDC, 52.

18. French Collection, HSWDC, 54.

19. Marshall D. Wright, The National Association of Base Ball Players, 1857-1870 (Jefferson, NC and London, McFarland, 2000), 98.

20. Nineteenth Century Stars (Kansas City, MO: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996), 101.

21. Wright, The National Association, 15.

22. SABR, Nineteenth Century Stars, 106.

23. French Collection, HSWDC, 55.

24. The “Presidential Grounds,” later called the “White Lot,” is now commonly known as the Ellipse.

25. French Collection, HSWDC, 55.

26. John P. Rossi, The National Game: Baseball and American Culture (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2000), 5.

27. The “trophy ball” was, in reality, the game ball that contained the clubs’ names and the score printed neatly on it. It was customarily lacquered for protection and preservation and given to the captain of the winning club with great pomp and circumstance.

28. French Collection, HSWDC, 65. Mr. French himself “presided” over the gala affair.

29. Wright, The National Association, 117.

30. Bealle, The Washington Senators, 11.

31. William J. Ryczek, When Johnny Came Sliding Home: The Post-Civil War Baseball Boom, 1865-1870 (Jefferson, NC and London: Mcfarland, 1992), 116. Curiously, the team did not play the newly formed Washington Olympics in 1866. That team, initially organized by Washington resident and former Civil War soldier Nicholas Young, would in the early 1870s overtake the Nationals as the area’s top team. Young himself was to become an extraordinarily important figure in the development of the game during the next several decades. He was not only a founding member of the National League in 1876, the same major league that exists to this day, but he also ran a school for umpires in Washington, DC. In his later years, he became one of the 19th century’s elder spokesmen for the game of baseball. Frank Ceresi, Mark Rucker, and Carol McMains, Baseball in Washington, DC (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2002), 11.

32. The goal of Jones and Gorman’s to make the western tour one of historic proportions is clearly reflected in the ball club’s Constitution, which was revised on April 1, 1867, less than four months before the tour. The Constitution states that the club’s “object shall be to improve, foster and perpetuate the American game of baseball and advance socially and physically the interests of its members.” French Collection, HSWDC, 25.

33. Ryczek, When Johnny, 116. Wright’s occcupation would be listed as that of Treasury Department clerk, although apparently young George earned a few extra dollars as “clerk of Cronin’s cigar store and baseball headquarters,” according to historian and author Morris Bealle. See Bealle, The Washington Senators, 6.

34. Wright, The National Association, 116.

35. Ryczek, When Johnny, 118. Bealle, The Washington Senators, 6.

36. French Collection, HSWDC, 210, and The Ball Players’ Chronicle, July 18, 1867. In the revised Constitution for the Nationals, dated April 1, 1867, Chadwick became an ‘honorary member’ of the ball club. French Collection, HSWDC, 23.

37. Henry Chadwick, The Ball Players’ Chronicle, Vol. 1, No. 7, July 18, 1867.

38. Henry Chadwick, The Ball Players’ Chronicle, Vol. 1, No. 7, July 18, 1867.

39. Ironically, the whipping at the hands of the Nationals ignited the Red Stockings into immediate action. Within two years, they would field the first professional team, do a tour of their own, and win every game they played in 1869. They would travel to Washington, D.C. and beat both the Nationals and the Olympics during their famous 1869 tour.

40. The team’s celebrity with the ladies apparently continued when they returned to Washington. A yellowed column in the French materials, written more in the style of a fashion guide than a sports section, reports that amongst the fans watching the Nationals in August 1867 were “several hundred ladies, who watched with glistening eyes peering from beneath charming little jockey hats, saucily perched forward and dainty bugle trimmed parasols elevated more from force of habit than from necessity.” French Collection, HSWDC, 210.

41. Ryczek, When Johnny, 122, citing the Henry Chadwick Scrapbooks.

42. Albert Spalding would become one of the most influential figures in the history of the game. The teenager became an excellent pitcher, winning over 250 games during his playing career. He then extended his influence as the longtime owner of the Chicago White Stockings and eventually opened a sporting goods company, Spalding and Brothers, that would make him a millionaire by the end of the century. Spalding is a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

43. Ryczek, When Johnny, 124, citing the Spirit of the Times, August 3, 1867.

44. French Collection, HSWDC, 193. At one point the Nationals were winning, 33 to 0.

45. Ryczek, When Johnny, 126, citing the Spirit of the Times, July 20, 1867.

46. In a sense the hoopla surrounding the presidential meeting and visit arranged by the Nationals in 1865 predated the famous “Presidential First Pitch” tradition that was to begin 60 years later when President Taft threw out the first pitch to inaugurate the 1910 major league season.

47. In 1867, the very year of the Nationals’ grand tour, the Washington Alerts and Mutuals, two of the earliest African American ball clubs, formed in the District. Charles Douglass, son of Frederick Douglass, during the 1867 to 1870 time period played for both teams. In fact, as secretary of the Mutuals in 1870, Charles contacted the Nationals and successfully arranged access for his club to use the Nationals ball field for the Mutuals’ series with the visiting powerhouse Philadelphia Pythians black ball club. Charles Douglass to J.C. White, September 10, 1869, Leon Gardiner Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

48. See for example, Ryczek, When Johnny, 126, citing the Henry Chadwood Scrapbooks. The annual Spalding Guides were published in the late 19th century by the sporting company owned by the very same Albert Spalding who led the Forest City club to the victory over the Nationals — their only defeat. Bealle, The Washington Senators, 7-8.