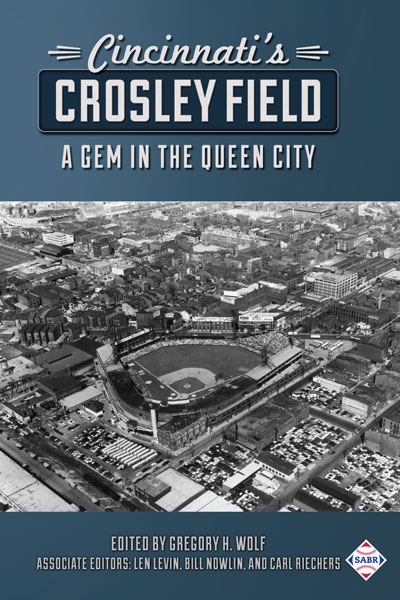

Evolving Home Run Distances at Crosley Field

This article was written by Greg Rhodes

This article was published in Crosley Field essays

On the eve of the opening game of the 1919 season in Cincinnati, veteran baseball writer Jack Ryder predicted that no batter could hit a pitched ball out of vast Redland Field (renamed Crosley Field in 1934).1

On the eve of the opening game of the 1919 season in Cincinnati, veteran baseball writer Jack Ryder predicted that no batter could hit a pitched ball out of vast Redland Field (renamed Crosley Field in 1934).1

Ryder was not crazy. He had covered the Reds since 1905, and in the seven years he had watched the Reds at Redland Field, he had never seen an over-the-fence home run at the yard. And for good reason. It was the Deadball Era, a time of “scientific hitting” that emphasized placement as much as power. And Redland Field was enormous. Like most ballparks of the era, Redland Field used the street grid as a guide for locating fences. No attention was paid to establishing distances at what we would think of today as a challenging home-run target. Redland’s dimensions, according to a 1911 architectural plan of the park, listed the distances as 390 feet to right field, 420 to deep right-center field (the deepest part of the ballpark) and 360 to left.2

Changes in the game in the early 1920s made the over-the fence home run more likely and more popular. Players began swinging for the fences and hitting the ball farther than ever. Still, Ryder’s prediction of no over-the-fence home runs at Redland held for two more seasons. The barrier finally fell on May 22, 1921, not to a major leaguer, but to Negro league slugger John Beckwith. The Cincinnati Cuban Stars rented Redland Field for their home games when the Reds were on the road, and Beckwith, playing for the visiting Chicago Stars, hit one over the left-field wall.3

The first official major-league home run came a few days later, on June 2, by Reds outfielder Pat Duncan. Duncan also deposited his home run over the left-field wall. The ball struck a surprised policeman on York Street, just beyond the wall. Duncan, who never showed much power in his major-league career, proved to be adept at a home-run trot. “Pat took his own time going about the paths,” wrote an admiring Ryder watching the dawn of the home-run era in Cincinnati.4

Duncan and Beckwith had conquered the left-field barrier, but what about center and right? On July 25, 1921, the New York Yankees and Babe Ruth stopped at Redland Field for an exhibition game. Ruth, who had a phenomenal 54 home runs in 1920, and had 36 by the time the Yankees appeared in Cincinnati, drew a large crowd. Most came to see if the Babe could hit one out of the park. In the fifth, with the bases loaded, Ruth sent a long, high drive over the center-field fence. Ryder estimated the distance at 450 feet. In the seventh inning, the Babe hit a low liner to deep right-center that cleared the fence in front of the bleachers.5 Years later the Babe recalled those home runs: “Believe me, neither of them was a dipsydoo.”6

Ruth’s blasts, as majestic as they were, had little immediate impact, for there weren’t many Babe Ruths playing in Cincinnati or in the National League The first home run to clear the right-field fence in an official league game is credited to Walton Cruise of the Boston Braves, on July 17, 1922.7 It was not until 1929, eight years after Ruth’s exhibition home run and 17 years after the park opened, that the first official home run was hit over the center-field wall, a drive off the bat of Reds center fielder Ethan Allen.8 And that was after the Reds shortened the fences. In 1927, the Reds added about 5,000 extra ground-level box seats in front of the original grandstand. This required the moving of home plate out some 20 feet, reducing the outfield dimensions to 339 feet to left field, 395 to dead center field (and 400 feet to deep right-center) and 377 feet to right.9

The Reds averaged only 5.2 home runs a year at Crosley Field in the 1920s, and many of those were inside the park. Visiting teams fared no better. From 1920 to 1937, the Reds and their opponents combined for 371 home runs at Redland/Crosley Field while combining for 1,288 on the road. Even Mel Ott, the NL’s reigning home-run hitter in the 1930s, hit fewer home runs at Crosley than in any other NL park. As baseball analyst Greg Gajus put it, Crosley Field was “the Astrodome of the 1920s and 1930s.” The long-ball revolution of the ’20s and ’30s passed right by Cincinnati.10

In 1937, the Reds once again shortened the home-run distance, moving home plate out another 20 feet. Unlike the 1927 relocation, the 1937 move was done just to bring the home run into play. The Reds had led the league in road home runs in 1935, 1936, and 1937, but the power was wasted at home. According to Lee Allen in his 1948 book The Cincinnati Reds, owner Powel Crosley read a suggestion from a fan to move home plate, and Crosley ordered the change.11 The move reduced the distance to right and left by 11 feet and to center by 20 feet. The new dimensions were 328 feet to left, 387 to dead center, and 366 to right.

The effect was dramatic. The Reds hit 50 home runs at home in 1938, more than twice as many as they had ever hit before in the vast confines of Crosley. Ival Goodman set a club home-run record in 1938, with 30 home runs, easily breaking the old record of 19.12

The only changes to the dimensions of Crosley after 1938 came in the 1940s and 1950s when the club reduced the distance to right field by 24 feet with the addition of seats in front of the original bleacher section.13 The Reds also changed the height of the center-field fence in 1964, adding nine feet in a wooden extension that sat atop the old concrete wall. The extension was necessary to block headlights and glare from the new expressway that opened just beyond the center-field wall in 1963. At first, the club left the home-run line at the top of the old wall; any ball hitting the wooden extension was a home run. In 1967, after several controversies, the club put the entire wall into play.14

GREG RHODES, a former chair of the Hoyt-Allen SABR Chapter of Cincinnati, is currently the Cincinnati Reds team historian. He was the founding director of the Reds Hall of Fame and Museum and served as director from 2003-2007. Two of his eight baseball books received The Sporting News-SABR Research Award (Reds in Black and White, with co-author Mark Stang, in 1999 and Redleg Journal, with co-author John Snyder, in 2001), and his book Big Red Dynasty, with co-author John Erardi, was a finalist for the 1998 Seymour Medal.

Notes

1 Greg Rhodes and John Erardi, Crosley Field (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 1995), 64.

2 Based on calculations by Mike Weaver, Crosley Field historian and model builder, from blueprints of Redland Field (Harry Hake & Partners, architects), from the collections of the Cincinnati Historical Society.

3 “Ball Goes Over Wall,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 23, 1921: 9.

4 Jack Ryder, “Garden Wall Cleared by Duncan,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 3, 1921: 6.

5 Jack Ryder, “More Honors Fall to Swat King,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 26, 1921: 8.

6 Frank B. Grayson, Cincinnati Times Star, May 27, 1935.

7 Greg Rhodes and John Snyder, Redleg Journal (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 2000), 215.

8 “Notes of the Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 23, 1929: 26.

9 Greg Rhodes and John Snyder, Redleg Journal, 232.

10 Greg Rhodes and John Snyder, Redleg Journal, 281.

11 Lee Allen, The Cincinnati Reds (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948), 254.

12 John A. Mercurio, A Chronology of Cincinnati Reds Records (Scotch Plains, New Jersey: Kalyn Press, 1993), 3.

13 See the essay “Goat Run” by Greg Rhodes in this volume.

14 Lou Smith, “Clear Fence, or Run It Out.” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 4, 1967: 1.