Jews and Baseball

This article was written by Peter Dreier

This article was published in Spring 2024 Baseball Research Journal

Editor’s Note: On this page, Parts One and Two, which were published separately in the Spring 2024 and Fall 2024 issues of the Baseball Research Journal, are combined into one article as the author intended.

Sandy Koufax (SABR-Rucker Archive)

American Jews have long had a love affair with baseball. They have played baseball since the game was developed in the mid-1800s. Some have made it to the professional ranks and a few have climbed to the very top—the major leagues. Jews have also become coaches and managers at all levels of the sport, from Little League to the majors, in addition to being sportswriters, umpires, owners, and executives. But even Jewish baseball fans may be surprised to learn that the 19 Jews who played on major league rosters in 2023 represented the highest number for a season in history. Although 19 is the peak in the number of Jewish players, it is only 1.3% of all players on the 30 current teams. The highest proportion of Jews occurred in 1937, 1938, and 1951, when Jews represented 2% of all players, and the big leagues had only 16 teams. Yet even that 2% figure is somewhat misleading, as we’ll discuss.

This article examines the history of Jews and baseball. It provides, for the first time, the year-by-year and decade-by-decade levels of participation since 1901. It explores the ways that Jews’ involvement with baseball reflects changes in immigration patterns, demographics, Jewish culture, and the sport itself. It looks at the influence of anti-Semitism and the contributions of record-breaking Jewish players as well as sportswriters, managers, coaches, umpires, owners, executives, rebels, and change agents.

The primary sources of data on Jewish ballplayers are Jewish Baseball News (JBN) and the Jewish Baseball Museum (JBM), in addition to books that include profiles of Jewish players, biographies and autobiographies of players, newspaper and magazine articles, and the biographies published by the Society for American Baseball Research.1 JBN considers a player to be Jewish if he has a Jewish parent or converted to Judaism, does not practice another faith, and is willing to be identified as a Jew. But that definition can be difficult to apply, especially to players from earlier periods who were not asked or did not clarify how they identified in religious or ethnic terms. For example, some players have Jewish ancestry but were not raised as Jews, some were the offspring of intermarried parents and their religious identity is unclear, some married Jewish women but did not convert, some converted to Judaism after they ended their baseball careers, and some changed their names to avoid anti-Semitism.2

JEWISH IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES

Historians and sociologists look at American immigration in terms of being a “melting pot” or a “salad bowl.” In the former, immigrants seek to assimilate into the mainstream culture and, in the process of doing so, change that culture to incorporate different ideas, languages, and customs. In the latter, immigrants do not forge together into a common culture, but seek to maintain their distinct identities and cultures. The country’s history of racism, of course, conforms to neither model. Baseball has reflected these tensions. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, immigrants from Europe—first Germans and Irish, then Italians, Slavs, Czechs, Poles, and Jews—were not immediately attracted to baseball, since their primary concern was gaining an economic foothold in the new society. They also lacked the time or money to attend professional or semiprofessional games. But their children—and then subsequent generations—took to baseball. The rosters of minor and major league teams reflected the nation’s evolving demographics—with the exception of African Americans, who were excluded from the late 1800s until 1947.3

The first Jews arrived in what is now the United States during colonial times. They were mostly of Spanish and Portuguese descent, primarily from Brazil, Amsterdam, and England. By 1840, the American Jewish community had grown to about 15,000 people. The next wave of Jews arrived from Germany and Austria starting in the middle 1800s. By 1880, the Jewish population reached about 250,000. Between 1880 and 1920, more than 2 million Jews came to the US, primarily from Eastern Europe (Russia, Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova), seeking to escape violent anti-Jewish riots called pogroms. Most American Jews today are descendants of the third wave of immigration.4

Lipman Pike was one of the first group of players—and the only Jew among them—to accept payment in 1866 for playing baseball, putting them among the first “professional” ballplayers.5 Pike was born in New York in 1845 to Dutch Jewish parents. Pike began playing baseball as a teenager and in 1866, at 21, he agreed to play for the Philadelphia Athletics for $20 a week. That year he belted five home runs in one game, establishing his reputation as America’s first great slugger. Pike played for several professional teams until he retired in 1881. Upon his retirement, Pike took over his father’s Brooklyn haberdashery shop and ran it until he died of heart disease at the age of 48 in 1893.

When Jewish immigrants arrived from Eastern Europe, baseball was as foreign to them as ham. In 1903, the Jewish Daily Forward, a widely read Yiddish newspaper, published a letter from a Russian Jewish immigrant. “What is the point of a crazy game like baseball?” the reader wanted to know. “I want my boy to grow up to be a mensch, not a wild American runner.” “Let your boys play baseball and play it well,” Forward editor Abraham Cahan responded in the letters-to-the-editor column. “Let us not raise the children that they grow up foreigners in their own birthplace.”6

Baseball became a way for Jews to show that they wanted to be full-fledged Americans, even as they also sought to maintain their group identity.

The overcrowded Jewish immigrant neighborhoods of the early 1900s provided few parks or playgrounds for Jews to play baseball. In New York, young Jews learned to play versions of baseball—using broom handles for bats and manhole covers for bases—on the streets. Athletic-oriented children of early Jewish immigrants were more likely to focus on boxing, basketball, and track-and-field, sports where Jews rose to prominence in amateur and professional ranks.7

As Jewish families moved from the tenement ghettoes to working class areas like the Bronx, with more spacious playgrounds and ballfields, and as public schools and Jewish settlement houses (such as the Young Men’s Hebrew Association) fielded baseball teams, the sons of immigrants had more opportunities to play baseball. After World War II, like many other white Americans, many Jews moved to the suburbs, with more ballfields and public school teams. Starting in the 1950s, many Jews also played on Little League teams.

From 1920 through 1957, the Giants and Dodgers, but not the Yankees, tried to recruit Jewish players to attract Jewish fans, as New York City’s population at the time was about one-third Jewish. During those years, the Giants had 11 Jews on their rosters, the Dodgers had 10, while the Yankees had only three. Harry Danning, Sid Gordon, Phil Weintraub, Goody Rosen, and Harry Feldman played for at least five years for either the Giants or Dodgers.

In 1923, Mose Solomon led the Southwestern League with 49 homers and a .421 batting average. The Giants put him on their roster at the end of the season. Writers called him the “Rabbi of Swat.” In two games, he had three hits in eight at-bats for a .375 average. But he got into a dispute with manager John McGraw and was sent back to the minors, where he played until 1929.

In 1926, the Giants added infielder Andy Cohen to their roster. He was born in Baltimore, grew up in El Paso, and played baseball at the University of Alabama. He became the next “Great Jewish Hope.” Sent back to the minors for 1927, he returned to the Giants in 1928. An estimated 25,000 to 35,000 fans, many of them Jewish, came to the Opening Day game at the Polo Grounds. Cohen drove in two runs and scored two more in the Giants’ 5–2 victory. In his three years with the Giants, he had a .281 batting average, but he returned to the minors after the 1929 season and never played in the majors again.

Like ballplayers in general, many Jewish players played for one season, or just a handful of games. For example, Robert Berman, born in New York City in 1899, graduated from high school, went to a Washington Nationals tryout, played in two games during the 1918 season, then spent a few years in the minors. He later played for barnstorming semipro teams, including an all-Jewish team, the South Philadelphia Hebrews, and the House of David team (which, despite its name, had few Jews). Then he returned to college and spent 43 years (1925–68) as a high school coach in New York.8

Andy Cohen played shortstop and second base in three seasons with the New York Giants. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

THE RISE, FALL, AND RISE OF JEWISH MAJOR LEAGUERS

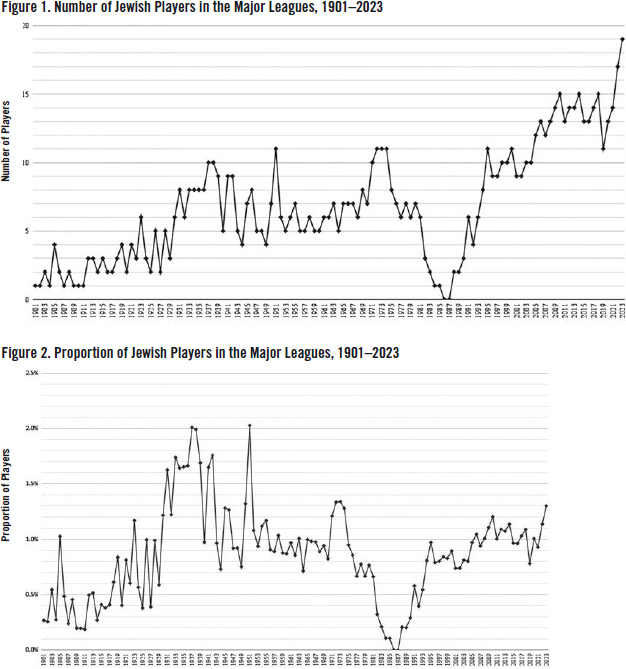

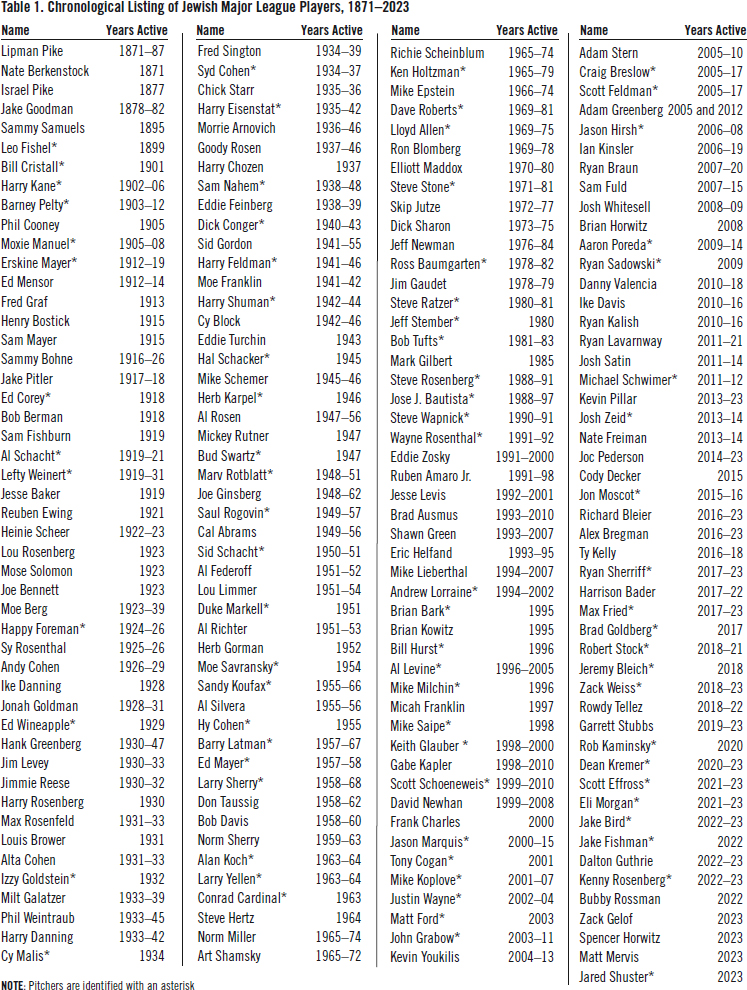

Since 1871, 193 Jews have played in the major leagues, identified in Table 1 (see Appendix below). Six, including Pike, played before 1901, when the American League (AL) joined the National League (NL) to form the two major leagues that are still active today. Since then, 187 identifiable Jews have played in the majors. Jews have thus composed about 1% of the roughly 19,000 big league players between 1901 and 2023. This is less than half of Jews’ proportion of the American population (about 2.5%) during those years. Jewish representation on major league rosters has fluctuated, as revealed in Figures 1 and 2.

(Click image to enlarge)

All but four of the 193 Jewish major leaguers were born in the US or Canada. Other than Jose J. Bautista, born in the Dominican Republic, the other three—William Cristall (born in 1875), Reuben Cohen (who played under the name Reuben Ewing and was born in 1899), and Isidore “Izzy” Goldstein (born in 1908)—were all, by coincidence, born in Odessa (then in the Russian empire, now in Ukraine).9

Only five Jews played on major league teams during the first decade (1901–1910) of the twentieth century and in most years, there were only one or two Jews on big league rosters. By the second decade (1911–1920), an average of 2.4 Jews wore major league uniforms each year, ranging from 0.2% to 0.8% of all players. The next decade saw an average of 3.5 Jews in uniform each year, ranging from 0.4% to 1.2% of all players. The 1930s saw a spurt of Jewish major leaguers, averaging 8.1 a year and ranging from 1.2% to 2% of all players. In the peak years of that decade—1937 and 1938—10 Jews played each season. In the 1940s, the average number of big league Jews declined to 6.1, while the proportion ranged from 0.7% to 1.8%. In the 1950s, the number averaged 6.3 and the annual proportion from 0.9% to 2.0%.

In the 1960s, MLB began expanding the number of teams and increased the total number of players. In that decade, the average number of Jews in the big leagues was 7.4, ranging from 0.7% to 1.0% of the total. The 1970s saw an uptick, with an average of 8.4 Jews in big league uniforms, ranging from 0.8% to 1.3% of all players.

In the 1980s, the average fell significantly to 2.4 and the proportion ranged from 0% to 0.8%. In 1984 and 1985, only one Jew wore a major league uniform and in 1986 and 1987, not a single Jew played in the majors. In the 1990s, an average of 7.6 Jews played in the majors, while the proportion ranged from 0.3% to 1.0%.

It is difficult to explain the low proportion of Jews in the majors during the 1980s and early 1990s. This was at the start of the influx of Latino players, but the increase was not yet sizable.10 There is no evidence that it was the result of anti-Semitism by scouts or ballclubs. It may simply be a statistical fluke in light of the relatively low number of Jews in the overall US population rather than changes in young Jews’ career aspirations or talents.

The number and proportion of major league Jews increased significantly in the twenty-first century. From 2000 to 2009, an average of 11.3 Jews were on rosters, ranging from 0.9% to 1.1%. Between 2010 and 2023, an average of 14 Jews played on major league teams each year, ranging from 0.8% to 1.3% of all players. The 19 Jewish players in 2023 matched the highest proportion (1.3%) since 1974.

Another way to look at Jews’ participation in baseball is to compare their proportion of all players to their proportion of the American population. Because the Census does not ask about religion, demographers have periodically sought other ways to identify and calculate the number of Jewish Americans, although their methods may not be as rigorous as the Census.

Based on best estimates, Jews represented 3.7% of the U.S. population in 1937—the highest it has ever been. That year and the following one, Jews were 2% of all major league players—or 54% of their proportion in the overall population. In 1951, Jews’ representation in the population had fallen to 3.5%, and Jews’ proportion of major league players was once again 2%—or 57% of their proportion in the total population.11 In 2023, Jews were 2.2% of the US population, and as previously mentioned, 1.3% of all major leaguers.12 This represents 59% of their proportion of the nation’s population—an all-time high.

CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS

Several demographic and sociological factors explain the increase in Jewish ballplayers in this century. The proportion of Americans living in California increased from 6.6% in 1950 to 10.4% in 1980 to 12% in 2010, while the proportion living in Florida grew from 1.7% to 4.3% to 6.1% in those years. After World War II, Americans Jews were in the forefront of moving from the East Coast and Midwest to California and Florida and from cities to suburbs. The Sunbelt allows for longer baseball seasons, and suburban public high schools and private high schools have more athletic resources (both in facilities and coaching) than urban public schools. Moreover, recent Jewish ballplayers have been much more likely than their predecessors to attend college and have received athletic scholarships. More than the earlier generations of Jewish players who had immigrant parents, recent players have parents who are more likely to support their sons’ pursuit of careers in sports.

Until the 1950s, most Jewish major leaguers were sons of immigrants. Many of their parents adhered to strict Jewish customs. Most of their offspring followed some, if not all, of those traditions. Interfaith marriages were almost taboo within the Jewish community. By the late twentieth century, most Jews were two or three generations removed from the immigrant generation. Interfaith marriages became more widely accepted. Like Jews in general, today’s Jewish players are more likely to be offspring of interfaith parents.

Some Jewish players were the sons not only of interfaith but also interracial couples, such as Ruben Amaro Jr. (son of a Jewish mother and Mexican-Cuban Catholic father who played in the majors), Jose J. Bautista (who was born to a Dominican father and an Israeli mother, had his bar mitzvah in the Dominican Republic, married a Jew, and kept a kosher home), Micah Franklin (son of a Jewish mother and African-American father), Kevin Pillar (son of a Jewish mother and Christian father), and Rowdy Tellez (who has a Jewish mother and Mexican Catholic father).

In the first half of the 1900s, few American men attended college. Among those born between 1906 and 1915, only 9% attended college.13 Few major leaguers born in that period did so. In fact, many dropped out of high school to join a minor league team, which was, in their minds, better than working on a farm or in a factory. Players and managers often called players with even one year of higher education “college boy,” not always meant as a compliment.

In the early 1900s, Jewish ballplayers were more likely than their non-Jewish teammates to have finished high school and even gone to college. Among the Jewish players who were born before 1900, 20% attended college. Among those born between 1900 and 1919, 52% went to college, even if they didn’t graduate. For example, Hank Greenberg, born in 1911, dropped out of New York University to play pro ball.

After World War II, more American men, and more pro ballplayers, attended college, thanks to the federal Serviceman’s Readjustment Act (“GI Bill”) and an increase in athletic scholarships. Among males born between 1930 and 1939, 29% attended college, but among Jewish major leaguers born in that period, 67% did. More than three-quarters of Jewish players born between 1940 and 1959 (76%) and 1960 and 1979 (79%) attended college.

By the twenty-first century, most male high school graduates had some college experience. Among those born between 1980 and 1989, 59% attended college.14 Among Jewish major leaguers born during that decade, 93% attended college.

The 22 Jewish major leaguers who played in 2022 (17 players) and 2023 (19 players) provide a window into the transformation of Jewish and American life.

Sixteen of this group of 22 grew up in Southern, Southwestern, and Western states with post war population booms—13 in California, two in Florida, and one in New Mexico. Eighteen went to high schools in the suburbs. Nineteen (86%) have attended college. At least 11 have one non-Jewish parent, at least two of whom later converted to Judaism. Only nine had a bar mitzvah. Few claim to be religious but most of them feel an affinity with their Jewish identity. For example, 14 have played for Team Israel in the World Baseball Classic and several others have said they’d like to do so.15

Harrison Bader, born to a Catholic mother and Jewish father, grew up in the New York suburbs and attended Horace Mann high school. The family never attended synagogue and Bader didn’t have a bar mitzvah. As his father explained in early 2023, while growing up, Bader didn’t identify either as Jewish or Catholic, “but has talked to me recently about converting to Judaism. He’s spoken to rabbis in New York about this. It is on his mind.”16 He attended the University of Florida on a baseball scholarship. He intended to play for Team Israel in 2023 but injuries kept him from doing so.

Jake Bird was raised in Valencia, California, to a Catholic mother and a half-Jewish father (giving him a Jewish grandmother and non-Jewish grandfather). The family didn’t attend a synagogue or Passover seders and Jake did not attend Hebrew school or have a bar mitzvah. After pitching and playing outfield for West Ranch High School, he attended UCLA, where he pitched for the Bruins for four seasons, was an Academic All-American, and graduated in 2018 with a degree in economics and a 3.62 grade point average. He played for Team Israel in 2023.

Richard Bleier’s father was born Jewish and his mother converted to Judaism. He grew up in South Florida, where he went to Hebrew school and had a bar mitzvah at Beth Am Israel, a Conservative synagogue in Cooper City. The family celebrated the High Holidays, had annual Passover seders, and lit Sabbath candles each week. Growing up, he played basketball and roller hockey at the local Jewish Community Center and said that “My dad would take me out of Hebrew school if I had baseball practice.” He played for Florida Gulf Coast University. Bleier and his wife, who is Catholic, “try to respect both of our traditions.”17 They don’t attend church or temple, but in 2022 they lit Hanukkah candles every night and also had a Christmas tree. They gave their daughter Murphy, now 3 years old, a Hebrew middle name—Adira. He played for Team Israel in 2013 and 2023.18

Alex Bregman’s father is Jewish. His mother was born Catholic but converted to Judaism. He had his bar mitzvah at Temple Albert in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He played for Louisiana State University.

Scott Effross grew up as a member of Congregation Shir Shalom in Bainbridge, Ohio, where he celebrated his bar mitzvah in 2006. He wears a Star of David necklace when he pitches. He played for Indiana University. He announced he would play for Team Israel in the 2023 WBC, but changed his mind due to injuries.19

Jake Fishman is the son of Harris Fishman and Cindy Layton.20 He attended Hebrew School and had his bar mitzvah at Congregation Klal Yisrael in Sharon, Massachusetts. He graduated from Union College, where he played baseball. Fishman played for the Israeli team in 2017 and 2023, and in the 2021 Olympics.21

Max Fried grew up in Santa Monica, California, with two Jewish parents. He attended synagogue on the High Holidays and had a bar mitzvah. In 2009, at age 14, he pitched for the US baseball team that won the gold medal in the Maccabiah Games in Israel. He was drafted out of Harvard-Westlake High School in Los Angeles and signed a contract without going to college.22

Zack Gelof grew up in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, where he attended Hebrew school at the Seaside Jewish Community but did not have a bar mitzvah. His parents are both attorneys. He attended Cape Henlopen High School (where he was class president for four years), then played for the University of Virginia.

Dalton Guthrie’s father Mark, who pitched in the majors from 1989 to 2003, is Christian. His mother, Andrea Balash Guthrie, is Jewish, the daughter of immigrants who fled Hungary in the 1950s. He grew up in Sarasota, Florida, and attended the Goldie Feldman Academy at Temple Beth Sholom before transferring to public school. He graduated from Venice High School, then played for the University of Florida. Team Israel recruited Guthrie, but he decided to spend the time in spring training in hopes of making the Phillies roster. But he’d like to play for Team Israel in the future. “My grandparents would be excited if I played for Team Israel,” he explained. “I guess I’ve always considered myself half-Jewish, but I’m going to have to find out more about my Jewish background.”23

Spencer Horwitz had a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother. “I’ve been around the Jewish culture my whole life and I’ve grown to love it and just appreciate it and respect it,” he told an interviewer.24 He attended St. Paul’s School for Boys in Brooklandville, Maryland, and played baseball at Radford University. He played for Team Israel in 2023.

Dean Kremer was born and raised in Stockton, California. His parents are Israelis who moved to the US after they completed military service in Israel. His grandparents and extended family still live in Israel, where he had his bar mitzvah. Kremer grew up speaking Hebrew at home. He pitched for San Joaquin Delta College and the University of Nevada. Discussing the decision by Sandy Koufax not to pitch for the first game of the 1965 World Series because the game fell on Yom Kippur, Kremer said: “I would do the same.” He won a gold medal pitching for Team USA in the 2013 Maccabiah Games in Israel and won the MVP award while pitching for Team Israel in the European Championship in both 2014 and 2015. He pitched for Team Israel in the 2017 and 2023 World Baseball Classic.25

Matt Mervis, son of two Jewish parents, grew up in Potomac, Maryland, attended Georgetown Preparatory School, and played baseball for four years at Duke University, where he majored in political science.26 His grandmother lived in Israel before immigrating to the United States. He played for Team Israel in 2013.

Eli Morgan was born in Rancho Palos Verdes, California, to Diana and Dave Morgan, former deputy sports editor for the Los Angeles Times. He went to Peninsula High School and joined the baseball team at Gonzaga University as a walk-on. In March 2024, Morgan told several Jewish publications that he did not identify as Jewish and no longer wanted to be included in lists of Jewish players.

Joc Pederson was born to a Jewish mother and non-Jewish father. On his mother’s side, the family tree extends back to membership in a San Francisco synagogue in the mid-1800s. Pederson’s mother, Shelly, trekked to her late father’s old synagogue to find proof of Joc’s Jewish heritage so he could play for Team Israel in 2013.27 He played for Team Israel again in the 2023 WBC. He went directly from Palo Alto High School to the minor leagues.

Kevin Pillar was born to a Jewish mother and non-Jewish father, grew up in West Hills (a suburban part of Los Angeles) and went to Chaminade College Prep. He played for California State University at Dominguez Hills, graduating with a degree in mathematics.28

Kenny Rosenberg was born in Mill Valley, California, a suburb of San Francisco, to a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother.29 He attended Tamalpais High School before playing for California State University, Northridge. He explained: “I grew up in a largely non-religious household. However, I had a bunch of Jewish friends and attended my fair share of bar and bat mitzvahs. I also have been to two Jewish weddings and they were both an absolute blast! The energy on the dance floor is unparalleled.”30

Bubby Rossman was born in La Habra, California, to a Jewish mother and non-Jewish father. “I don’t remember ever going to a synagogue. I didn’t go to Hebrew school. I didn’t have a bar mitzvah. My high school was 60–70% Latin. I was the only Jew only on my baseball team. I didn’t know any Jews in my high school. My mom tried to incorporate it [Jewish identity] into my life.” He went to La Habra High School and pitched for California State University at Dominguez Hills. To play for the Israel team in the European baseball league, he visited Israel and got dual citizenship. “When I was in Israel I went to synagogue and became more familiar with my heritage. I wanted to know what my grandparents and great-grandparents went through. If I get married, I’d like my kids to get to go to understand their Jewish identity.”31 He played for Team Israel in 2023.

Ryan Sherriff was born in Culver City, a Los Angeles suburb, attended Culver City High School, then played for West Los Angeles College and Glendale Community College. His parents are Jewish and his maternal grandparents were Holocaust survivors who spent time in concentration camps. He pitched for Team Israel in 2017.

Jared Shuster grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts, the son of two Jewish parents, Bennett and Lori Shuster.32 He attended New Bedford High School before transferring to Tabor Academy in Marion, Massachusetts. He played college baseball at Wake Forest University.

Garrett Stubbs was born in San Diego to a Jewish mother and a Catholic father. He was raised Jewish, attended Hebrew school every Wednesday from age eight to 13, and celebrated his bar mitzvah at Temple Solel in Cardiff-by-the-Sea, a San Diego suburb. He played for the University of Southern California Trojans from 2012 to 2015 and won the 2015 Johnny Bench Award as the nation’s best collegiate catcher. He played on Team Israel in 2023.

Rowdy Tellez was born in Sacramento, California, to a Jewish mother and non-Jewish father. His grandfather played in the Mexican Baseball League. He jumped directly from Elk Grove High School in California to the minor leagues.

Zack Weiss began blowing the Rosh Hashana shofar at age 8 at Congregation B’nai Israel in Tustin, California. He played for UCLA. He became a dual US-Israeli citizen in 2018 and played for Team Israel in the 2021 Olympics in Tokyo and in the 2023 World Baseball Classic.33

These 22 players’ connection to their Jewish identity ranges from those who were raised with Jewish beliefs and practices to those who only began to explore their Jewish heritage as adults. In this way, they mirror the experiences of twenty-first century Jewish Americans and the spectrum of identification found among those in their age group.

ANTI-SEMITISM

As millions of immigrants arrived in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, America became a cauldron of nativist and anti-Semitic vitriol. Jews were the subject of vicious stereotypes in films, books, plays, and other forms of popular culture. They faced discrimination in jobs and housing. Colleges imposed quotas on Jewish students. Many hotels, resorts, and clubs barred Jews.34 Anti-Jewish stereotypes were common and widely promulgated. For example, during World War I, a US Army manual published for recruits stated, “The foreign born, and especially Jews, are more apt to malinger than the native-born.”35 Jews in general, and Jewish ballplayers, faced constant verbal and physical abuse.

Anti-Semitism was exacerbated by the 1919 Black Sox Scandal, when the Chicago White Sox threw the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. Gamblers Arnold Rothstein and former featherweight boxing champion Abe Attell, both Jews, were implicated in the fix. Auto magnate Henry Ford blamed Jews for the entire scandal. His anti-Semitic newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, published articles with titles such as “Jewish Gamblers Corrupt American Baseball” and “The Jewish Degradation of American Baseball.” In one article, Ford wrote, “If fans wish to know the trouble with American baseball, they have it in three words—too much Jew.”36

The Sporting News, the influential weekly baseball newspaper, blamed “outsiders” for threatening the sanctity of baseball. The anti-Jewish stereotypes were unmistakable. The paper claimed that “a lot of dirty, long-nosed, thick-lipped, and strong-smelling gamblers butted into the World Series—an American event, by the way.”37

Like other Jewish players, Andy Cohen, who played for the New York Giants from 1926 to 1929, had to endure being called epithets like “kike” and “Hebe.” After a spectator called him “Christ Killer” during a minor-league game, Cohen, bat in hand, found the offending fan and shouted, “Yeah, come down here and I’ll kill you, too.”38

Prior to the 1930s, many Jewish ballplayers changed their names, hoping to avoid anti-Semitism. At least five players named Cohen played in the big leagues during that period, but only one, Andy Cohen, used his birth name. The others called themselves Cooney, Bohne, Corey, and Ewing. Joseph Rosenblum played one game in the major leagues in 1923 as Joe Bennett. (The losing pitcher for the Philadelphia Phillies that day was Lefty Weinert. It marked the first time that two Jewish teammates appeared in the same major-league game).

While a member of the minor-league Los Angeles Angels in the 1920s, Jimmie Reese, who would play for the New York Yankees and St. Louis Cardinals in 1930– 32, played in an exhibition game against Hollywood celebrities and retired major leaguers. The celeb team’s battery consisted of two Jews—pitcher Harry Ruby, the composer of many hit songs, including “I Wanna Be Loved By You,” “Three Little Words,” and “Who’s Sorry Now?” and minor-league catcher Ike Danning. Rather than use conventional hand signals, Danning called the game in Yiddish, certain that no Angels players would understand. Reese had four hits. After the game a surprised Ruby remarked, “I didn’t know you were that good a hitter, Jimmie.” Reese said, “You also didn’t know that my name was Hymie Solomon.”39

Sportswriters of that era routinely mentioned players’ religion when known. Barney Pelty—an outstanding pitcher for the St. Louis Browns from 1903 to 1912— was called the “Yiddisher curver.”40 While pitching for the Brooklyn Dodgers’ minor league franchise in Allentown, Pennsylvania, in 1936, Sam Nahem used an alias, “Sam Nichols,” but his secret wasn’t very well-hidden. The Allentown Call noted that “The Allentown Brooks this season may have one of the rarities of organized baseball, an all-Jewish battery,” explaining that the catcher, Jim Smilgoff, was “of Hebraic extraction” while Sam Nichols was “also of Jewish parentage.”41

Sportswriters of that era routinely mentioned players’ religion when known. Barney Pelty—an outstanding pitcher for the St. Louis Browns from 1903 to 1912— was called the “Yiddisher curver.”40 While pitching for the Brooklyn Dodgers’ minor league franchise in Allentown, Pennsylvania, in 1936, Sam Nahem used an alias, “Sam Nichols,” but his secret wasn’t very well-hidden. The Allentown Call noted that “The Allentown Brooks this season may have one of the rarities of organized baseball, an all-Jewish battery,” explaining that the catcher, Jim Smilgoff, was “of Hebraic extraction” while Sam Nichols was “also of Jewish parentage.”41

A 1938 poll found that about 60 percent of Americans held a low opinion of Jews, labeling them “greedy,” “dishonest,” and “pushy.” In 1939, a Roper poll found that only 39 percent of Americans felt that Jews should be treated like other people. Fifty-three percent believed that “Jews are different and should be restricted” and 10 percent believed Jews should be deported. A 1945 survey found that 23 percent of Americans would vote for a congressional candidate who declared “himself as being against the Jews.”42

As Jews gained more acceptance and self-confidence in America, fewer Jewish ballplayers changed their names, but anti-Semitism didn’t disappear.

During spring training in 1934, the Giants were staying in a hotel in Florida with a “no Jews” policy. The hotel refused to allow two Jewish players—Phil Weintraub and Harry Danning, Ike’s more famous younger brother—to register. Manager Bill Terry threatened to take the entire team to another hotel. The hotel manager backed down.43

Hank Greenberg, the first Jewish superstar, who played from 1930 to 1947, faced persistent anti-Semitism. Although he wasn’t religious, Greenberg was proud of his Jewish identity and knew he was a role model for Jews and a symbol of his people to non-Jews. On September 18, 1934, when he was leading the American League in RBIs and his Detroit Tigers were in first place, he attended Yom Kippur services rather than play in that day’s game. When he arrived at the synagogue, the congregation gave him a standing ovation.

Detroit was among the country’s most anti-Semitic cities—home of not only Ford but also radio priest Charles Coughlin. When the US government agreed to accept some Jewish refugees from Germany in the mid-1930s, Coughlin said, “Send the Jews back where they came from in leaky boats.”44

According to fellow Tiger Birdie Tebbetts, “There was nobody in the history of the game who took more abuse than Greenberg, unless it was Jackie Robinson.”45

During his playing career, the 6-foot-4 Greenberg occasionally challenged bigots to fight him one-on-one. He often said that he felt every home run he hit was a home run against Hitler. “How the hell could you get up to home plate every day and have some son-of-a-bitch call you a Jew bastard and a kike and a sheenie and get on your ass without feeling the pressure?” he said. “If the ballplayers weren’t doing it, the fans were. I used to get frustrated as hell. Sometimes I wanted to go into the stands and beat the shit out of them.”46

During the 1935 World Series, umpire George Moriarty warned Chicago Cubs players to stop screaming anti-Semitic insults at Greenberg and Jewish umpire Dolly Stark (whom Cubs players called a “Christ killer”). By the time the game was over, Moriarty had cleared much of the Cubs dugout. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis fined Moriarty $250 for his actions but did not discipline the bigoted players.47

In 1938, when Greenberg hit 58 home runs, two short of Babe Ruth’s 1927 record, he faced regular anti-Semitic insults from fans who hated the idea that a Jew might overtake the beloved Babe’s milestone. There is evidence that as Greenberg closed in on the record late in the season, pitchers pitched around him to make sure he didn’t break it.48 Tebbetts recalled that one pitcher shouted to Greenberg, “You’re not going to get any home runs off me, you Jewish son of a bitch.” Greenberg hit two home runs against him.49

But Greenberg had his allies. St. Louis Browns first baseman George McQuinn “deliberately dropped a foul ball to give me another chance,” Greenberg remembered.50

According to Greenberg, “Being Jewish and being the object of a lot of derogatory remarks kept me on my toes all the time. I could never relax and be one of the boys, so to speak. So I think it helped me in my career because it always made me aware of the fact that I had a little extra burden to bear and it made me a better ballplayer.”51

After Greenberg, the next Jewish superstar was Al Rosen. During his playing career, from 1947–56, all with the Cleveland Indians, Rosen banged 192 homers, drove in 717 runs, and batted .285. He played in every All-Star Game from 1952–55 and won the American League MVP Award in 1953, leading the league in homers (43) and RBIs (145) while batting .336.

Rosen grew up Miami—in the only Jewish family in a Cuban neighborhood. He got into many fights when others called him anti-Semitic names, which led him to become an excellent boxer in college and in the military during World War II. He dropped out of the University of Florida to play in the minors, where he constantly faced anti-Semitic taunts, especially in Southern towns. The anti-Semitism didn’t stop when he reached the majors. After a White Sox player called him a “Jew bastard,” Rosen walked over to the dugout and asked whoever called him that name to step forward. No one did. “When I was in the majors,” Rosen said, “I always knew how I wanted it to be about me….Here comes one Jewish kid that every Jew in the world can be proud of.”52

Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe recalled that behind Sandy Koufax’s back, his own teammates called him “this kike,” “this Jew bastard,” and “Jew sonofabitch…. They hated Jews as much as they hated Blacks.”53 After a spring-training night game in Miami during the mid-1950s, some Dodgers complained about having to ride a non-air-conditioned bus. Coach Billy Herman, sitting across from Koufax, yelled loudly, “You can give this damn town back to the Jews.” After a few moments of silence, Koufax tried to defuse the situation: “Now, Billy, you know we’ve already got it.”54

Ken Holtzman, the only Jew on the Chicago Cubs’ roster from 1966 to 1971, faced anti-Semitic bigotry from manager Leo Durocher. The poorly-educated Durocher resented Holtzman’s college education, his cerebral manner (he would read books in airport terminals while waiting for a flight), his ability to beat Durocher at gin rummy, and his strong pro-union attitude. Durocher (who also referred to Marvin Miller, the head of the players’ union, as “that goddam Jew bastard”) constantly berated Holtzman and called him a “kike” and “gutless Jew” in front of his teammates. In 1970, Durocher removed Holtzman from a game he was winning 6-4 with two outs in the fifth inning. Had he stayed in and gotten one more out, Holtzman would have been the winning pitcher. According to one analysis, “Holtzman’s background—specifically his upbringing as an observant Jew who refused to pitch on Jewish holidays and who adhered to Jewish dietary laws—contributed to Durocher’s increasingly antagonistic behavior toward Holtzman.” Durocher demeaned other players as well; he referred to Ron Santo as a “wop,” called the college-educated Don Kessinger a “dumb hillbilly,” and degraded the Cubs’ Black players. The players rebelled and by the 1972 All-Star game, Durocher was fired.55

MISTAKEN IDENTITY

Some players with Jewish-sounding names have been mistaken for Jews by fans, sportswriters, and players. The Jewish Baseball News website even has a “Not a Jew” section identifying non-Jewish players with Jewish-sounding names like Blum, Eckstein, Lowenstein, Rosenberg, Rosenthal, and Weiss.56 For example, Charley “Buck” Herzog, joined the New York Giants in 1908. Sportswriters wrongly assumed he was Jewish because of his name and facial features and claimed that he attracted fans among fellow Jews. “The long-nosed rooters are crazy whenever young Herzog does anything noteworthy,” one sportswriter wrote, adding that “there would be no let-up even if a million ham sandwiches suddenly fell among these believers in percentages and bargains.”57

Avowedly Christian ballplayers with Jewish ancestry are not considered Jews by Jewish Baseball News (nor by themselves), but that did not stop them from facing anti-Semitism. Charles Solomon (Buddy) Myer Jr. played for 17 years (1925–41) with the Washington Nationals and Boston Red Sox, won a batting title, was a two-time All-Star (although he played his first seven years before the first All-Star Game), and had a lifetime .303 batting average. Jewish sportswriters such as the Washington Post ’s Shirley Povich, who covered the Nationals every day, routinely referred to him as a Jew. After he led the AL in batting in 1935 with a .349 average, The Sporting News, baseball’s paper of record, reported that the Yankees were trying to purchase Myer’s contract from the Nationals. The headline on its story: “Yanks Hope to Dress in Myer a Tailor-Made Jewish Star.” The story said that the Yankees hoped that New York’s “big army of Jewish fans…would be lured into the park by a Jewish star.” Sportswriter Fred Lieb ranked Myer as the second-greatest Jewish player of all time, after Greenberg.58 (This was before Rosen and Koufax.)

Myer faced anti-Semitic abuse. Opposing players called him a kike. Pitchers threw at his head. In 1933, Yankees outfielder Ben Chapman (a notorious bigot who later taunted Jackie Robinson with racist slurs) intentionally spiked Myer when he slid into second base. The two players got into a fistfight that led to a benches-clearing brawl requiring police intervention. The next day, Povich wrote that Chapman “cut a swastika with his spikes on Myer’s thigh.”59 After AL President William Harridge fined and suspended both players, Myer protested. “Chapman had it coming to him and I gave it to him,” he said, recalling that he’d spiked him in the past. “I had to retaliate to stop him before he ended my baseball career.”60 Many newspapers reported the incident, but few mentioned its cause.

Myer is included in Peter S. and Joachim Horvitz’s The Big Book of Jewish Baseball, Burton A. and Benita W. Boxerman’s multi-volume Jews and Baseball, and Erwin Lynn’s The Jewish Baseball Hall of Fame.61 In 1992, he was inducted into the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame. These errors are understandable. His birth name was Charles Solomon Myer. And his father owned a clothing store.

But Myer wasn’t Jewish.

Myer was born in Ellisville, Mississippi, in 1904, the fourth of five children of Charles Solomon Myer and the former Maud Stevens. The family were originally German Jews but had converted to Christianity at least two generations before Buddy was born. When he died in 1974, his obituary listed him as a member of the First Baptist Church in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.62 “He was raised Baptist,” his son Dick said. “He didn’t think it was right when they inducted him into the Jewish Hall of Fame, but he didn’t correct them because he was afraid it would be taken the wrong way.”

Such misidentification was not left behind in the twenty-first century. On May 28, 2006, as part of the Florida Marlins’ Jewish Heritage Day promotion, the team gave away Mike Jacobs jersey T-shirts to young fans in attendance. The Marlins mentioned their third baseman in the promotion material for the event. But Jacobs isn’t Jewish.

Some lists of Jewish players incorrectly include Hall of Famer Lou Boudreau, but although he had a Jewish mother, he was raised as a Catholic and did not identify as a Jew. Some include Johnny Kling and Rod Carew, who both married Jewish women but did not convert to Judaism. Some writers have mentioned longtime player, pitching coach, and manager Larry Rothschild and former player and current San Francisco Giants manager Bob Melvin as Jews.63 Rothschild had a Jewish father and Melvin had a Jewish mother, but both were raised as and identify as Christians.

HALL OF FAMERS, ALL-STARS, AND RECORD BREAKERS

There are five Jews in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, not to mention the two who have served as president, Jeff Idelson (2008–19) and Josh Rawitch (2021–present). Two are players: Greenberg and Koufax. Marvin Miller was the first executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association. Barney Dreyfuss of the Pittsburgh Pirates and Bud Selig of the Milwaukee Brewers were owners (although Selig was inducted as a commissioner).

Twenty-two Jews have been selected to major-league All-Star teams, as shown in Table 2. Ryan Braun and Koufax each made the team six times, Greenberg (who missed all of three seasons and parts of two others for service during World War II) was selected five times, and Harry Danning, Al Rosen, and Ian Kinsler made it four times.64

Some additional facts of note about Jews and baseball’s record books:

- Three Jewish players have made the same All-Star game three times: 1939 (Greenberg, Morrie Arnovich, and Danning); 1999 (Brad Ausmus, Shawn Green, and Mike Lieberthal); and 2008 (Kevin Youkilis, Braun, and Kinsler).

- Four Jews have won the MVP Award: Greenberg (1935 and 1940) and Rosen (1953) in the AL; Koufax (1963) and Braun (2011) in the National League.65

- Seven Jews have won Gold Glove Awards: Green (1999); Lieberthal (1999); Ausmus (2001, 2002, 2006); Youkilis (2007); Kinsler (2016, 2018), Max Fried (2020–22); and Harrison Bader (2021).66

- One Jew has won the Rookie of the Year Award: Braun in the NL in 2007.67

- Lipman Pike led his league (the National Association 1871–73 and the National League in 1877 in home runs four times. Greenberg led the AL in homers four times (1935, 1938, 1940, 1946 in the AL). Rosen did it twice (1950, 1953 in the AL) and Braun once (2012 in the NL).

- League RBI leaders have been Pike in the National Association (1872), Greenberg (1935, 1937, 1940, 1946), and Rosen (1952–53) in the AL.

- Two Jews have won the Cy Young Award: Koufax (1963, 1965, 1966) in the NL and Steve Stone (1980) in the AL.68

- Koufax led the NL in wins in 1963, 1965, and 1966. Stone earned that honor in the AL in 1980.

- In 1951, Saul Rogovin had the lowest ERA of any pitcher in the AL.

- Koufax is the only NL pitcher to lead the league in ERA for five years in a row (1962–66). He was the major-league strikeout leader in 1961, 1963, 1965, and 1966.

Some major league records owned by Jewish players:

- Green set the record for most total bases in one game (19) on May 23, 2002. He went 6-for-6, with four home runs (tying the record), a double, and a single (his five extra-base hits tied the record), scored six runs, and had seven RBIs. Green’s four home runs tied the record (with 17 others) for most homers in one game.

- On August 22, 1917, Jake Pitler had 15 putouts at second base in a 22-inning game.

- On August 12, 1966, Art Shamsky became the first (and still only) player to hit three home runs in a game he didn’t start.

- Youkilis had 2,002 consecutive chances at first base without an error and 238 consecutive games at first base without an error. Those streaks ended on June 7, 2008.

- On April 6, 1973, Ron Blomberg of the Yankees became major-league baseball’s first designated hitter. Boston Red Sox pitcher Luis Tiant walked him on five pitches with the bases loaded.

- On August 1, 1918, Erskine Mayer participated in one of the greatest pitching duels in history. Starting for the Pirates against the Braves at Boston, he and Braves starter Art Nehf pitched scoreless baseball for 15 innings. Wilbur Cooper finally relieved Mayer with one out in the 16th inning and got the win when the Pirates pushed across two runs against Nehf in the 21st.69

On April 30, 1944, the New York Giants scored 26 runs in a game at the Polo Grounds against the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Giants’ Jewish first baseman, Phil Weintraub, knocked in 11 of those runs, one short of the record set by Jim Bottomley in 1924. He went 4-for-5, with two doubles, a triple, and a home run, as well as two walks. Mark Whiten of the St. Louis Cardinals tied Bottomley’s record in 1993. So Weintraub’s 11 RBIs in one game remains the third most in major league history, tied with Tony Lazzeri.70

The “wandering Jew” award goes to pitcher Craig Breslow, who played for 7 different teams during his 12-year career (2005–17). Breslow graduated from Yale, but Moe Berg, a graduate of both Princeton and Columbia University Law School, had two Ivy League degrees. Berg (1923–39) worked as a spy for the predecessor to the CIA and allegedly spoke 12 languages—“but,” a teammate once said, “he can’t hit in any of them.”

NOT QUITE A MINYAN

No major-league team has ever had a minyan—the quorum of 10 Jews required for a worship service. But there have been occasions when an unusual number of Jews were on the same team or on the field at the same time.

At Sid Gordon’s first major-league game, on September 11, 1941, the Giants had four Jewish players on the roster: Gordon, Morrie Arnovich, Harry Feldman, and Harry Danning. All four of them played in the same game on September 21. That number has never been surpassed. The 1946 Giants had five Jewish players— Arnovich, Gordon, Feldman, Goody Rosen, and Mike Schemer, the most Jews on one team in one season— but they were never all on the field at the same time.

On August 8, 2005, the Red Sox set an AL record when three Jewish players (Youkilis, Adam Stern, and Gabe Kapler) took the field at the same time. The following year, Breslow joined the Red Sox, setting an AL record of four Jews on the same roster during a season, but Stern had left the team by the time Breslow arrived. Breslow, Youkilis, and Kapler tied the record by playing at the same time in several games.71

There have been at least nine all-Jewish batteries, when a Jewish pitcher and Jewish catcher played on the same team and in at least one game together. These include Feldman and Danning (1941–42 Giants); brothers Larry and Norm Sherry, as well as Norm catching Koufax (1959–62 Los Angeles Dodgers); Rogovin and Joe Ginsberg (1950–51 Tigers); Jason Hirsh and Ausmus (2006 Houston Astros); Breslow and Ryan Lavarnway (2012 Red Sox); Eli Morgan and Lavarnway (2021 Indians); Bubby Rossman and Garrett Stubbs (2022 Phillies); and Max Lazar and Stubbs (2024 Phillies).72

There have been a handful of trifectas. On May 2, 1951, Rogovin was pitching for the Tigers, Ginsberg was catching, and Lou Limmer came to bat for the Philadelphia Athletics.73 Three times, a Jewish battery faced a Jewish hitter. On August 15, 2013, Breslow, pitching for the Red Sox, struck out Toronto Blue Jay Kevin Pillar with Lavarnway behind the plate. On June 22, 2021, with Lavarnway catching for the Indians, Morgan pitched to Cubs outfielder Joc Pederson three times. On August 10, 2024, in his major league debut, Max Lazar, pitching for the Phillies to catcher Garrett Stubbs, struck out the Diamondbacks’ Pederson.74

In the bottom of the second inning of Game Six of the 2021 World Series, Alex Bregman of the Astros flied out to right field against Braves pitcher Fried. The ball was caught by Pederson.

On September 18, 1996, near the Jewish High Holidays, the Brewers hosted the Blue Jays at County Stadium. When Shawn Green game to bat, he greeted Jesse Levis, the Milwaukee catcher, with a friendly “L’shana tova,” Hebrew for happy new year. Then, to Green and Levis’ surprise, home-plate umpire Al Clark offered his own “L’shana tova.” Clark had grown up as an Orthodox Jew.75

In 1966, Koufax and Ken Holtzman of the Cubs told their managers that they wouldn’t pitch on Yom Kippur. Instead they pitched the following day, September 25, at Wrigley Field. Koufax lost a 2–1 game to Holtzman. Both pitched complete games. Holtzman had a no-hitter going until the ninth inning, when he gave up two hits. Koufax gave up four hits on the day. Since then, Jewish starting pitchers have faced off four times: On June 20, 1971, Steve Stone of the Giants started against the Padres’ Dave Roberts. As a Yankee, Holtzman started a game against Roberts, then with the Tigers, on September 24, 1976, and again on June 22, 1977. Fried, with the Braves, battled Dean Kremer of the Baltimore Orioles on May 5, 2023.

With a few exceptions (including Greenberg, Koufax, Holtzman, Green, and Youkilis) most Jewish players have chosen to play on Yom Kippur. Some have wondered whether there was a “Koufax curse” for Jews who played on the holiest of Jewish holidays. One study identified 36 Jewish players—18 non-pitchers and 18 pitchers—whose teams have been in the World Series since 1966, the year of the Koufax-Holtzman match-up. In 120 games, teams are 53–67 (a .442 winning average) when a Jewish player plays on Yom Kippur. Teams won six of 23 games in which a pitcher is Jewish, a terrible .261 winning average. Although their teams performed poorly, the individual Jewish players performed relatively well. As a group, the hitters’ performance on Yom Kippur matched their career batting average and OPS. Pitchers’ performances have been mixed, with several good starts and relief appearances balanced against some poor games.76

JEWISH MANAGERS AND COACHES

At least nine Jews have managed big-league teams and at least six Jews have been major-league coaches, as shown in Table 3 in the Appendix.

Lipman Pike—the first Jewish professional ballplayer and the first home-run slugger—was a player/manager for the Cincinnati Reds (1877).

For most of Jacob (Jake) Morse’s career, he was an influential sportswriter in Boston, but in 1884 he managed the Boston Unions during the second half of the season. Born in 1860 in New Hampshire to Jewish immigrants from Bavaria, he was one of 10 children who grew up in Boston, where his extended family, including his uncles, operated a clothing store, worked as lawyers, and were active in politics. Morse attended Harvard and then Boston University’s law school. While in law school he wrote articles for several Boston newspapers. He graduated in 1884, the same year St. Louis millionaire Henry Lucas organized the Union Association to compete with the National League and American Association in protest of the owners of the two leagues adopting a reserve clause in players’ contracts.

Morse edited the Union Association Guide and became friends with Boston’s first baseman, Tim Murnane, who was also the field manager. Morse not only wrote articles about the Union Association and the Boston Unions for local papers but helped Murnane manage the team during the latter part of the season, although it is unclear what his responsibilities were. After the Union Association folded at the end of the season, Morse became the full-time sports editor for the Boston Herald, a position he held for 20 years. He also wrote a book, Sphere and Ash: History of Baseball, published in 1888. By 1892, he and Murnane—who by then was sports editor of the Boston Globe—became the administrative staff for the New England League, a minor league. In 1895, he became president of the New England Association, another minor league with teams in Massachusetts. In 1908, Morse founded Baseball Magazine, the first monthly periodical devoted to baseball.77

Louis (Louie) Heilbroner was an even more unlikely figure to become a major-league manager. He was the St. Louis Cardinals’ business manager and manager of concessions in 1900. He had no knowledge of baseball and, at 4-foot-9, had never played the game. But on August 19, 1900, Cardinals manager Patsy Tebeau quit. The team’s president and owner, Frank Robison, was desperate to find someone to replace him. He first offered the job to third baseman John McGraw, who turned it down. So Robison handed the job to Heilbroner, with the understanding that McGraw would actually manage the team from third base. (McGraw went on to become one of baseball’s great managers, briefly for the Orioles and then for the Giants). Heilbroner managed the Cardinals’ last 50 games and had a record of 23 wins, 25 losses, and 2 ties. When the season ended, the Cardinals hired Patsy Donovan to manage and Heilbroner returned to his job as business manager, which he held until 1902. In 1909, he founded Heilbroner’s Baseball Bureau Service, the first commercial firm to focus on baseball statistics.78

When a long minor-league career and a brief one in the majors with the Giants (1926–29), Andy Cohen managed in the minor leagues between 1939 and 1958. In 1960, he was a coach for the Phillies. After manager Eddie Sawyer stepped down after losing the first game of the 1960 season, the Phillies hired Gene Mauch as his replacement, and Cohen managed one game before Mauch could join the team. As a result, Cohen had a perfect 1–0 record as a big-league manager.

In 1963, he became the head coach at the University of Texas at El Paso, remaining in that position until 1978. Cohen Stadium in El Paso is named after Andy and his brother Syd, who pitched in the major leagues from 1934–37. The brothers grew up in El Paso and attended El Paso High School, where Andy was a star in basketball and football and Syd was a star in baseball and was captain of the basketball teams that went to the state finals in his junior and senior years.

Alon Leichman, assistant pitching coach for the Cincinnati Reds, was born in and grew up on a kibbutz in Israel. He played for Cypress (California) College and the University of California at San Diego. Leichman coached Team Israel at the 2017 World Baseball Classic in South Korea and Japan, then pitched for Israel at the 2019 European Baseball Championship, the Africa/Europe 2020 Olympic Qualification tournament, and the 2020 Summer Olympics, held in Tokyo in 2021.79

JEWISH UMPIRES

A 2017 article in USA Today claimed that John and Mark Hirschbeck and Tim and Bill Welke are the only sets of brothers to be major-league umpires.80 But brothers Israel and Lipman Pike both held that job during baseball’s early days. Israel was likely the first Jewish professional umpire, working in the National Association in 1875. Lipman also umpired after his playing days were over, in 1887 and 1889 in Double A and in 1890 in the NL.

Since 1900, at least four Jews have worked as major-league umpires, and each of them faced tragedy and/or scandal.

Dolly Stark was born on November 4, 1897, to a poor Jewish family on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. After his father died and his mother became blind, Stark was briefly homeless until a policeman arranged for him to live in an orphanage. Turning to baseball, the 115-pounder played second base in an industrial league and then in the minors from 1917–21 and tried out unsuccessfully for the Yankees and Nationals. A friend asked him to umpire a college game in Vermont, which led to more work in college and Eastern League games. After three weeks, his impressive performance led to his promotion to the NL, where he umpired from 1928–40, except during the 1936 season, when he and Bill Dyer formed the Phillies’ first radio announcing team on WCAU. He was the first big-league umpire to move around to be in position to make the right call. From 1923–36, during much of his umpiring career, he also coached the Dartmouth College basketball team.81

A trick knee forced Stark to retire from umpiring at the age of 44. No team would hire him as a manager, coach, or scout. He designed women’s clothes and briefly had a successful line of apparel called the Dolly Stark Dress. But he couldn’t make ends meet. He supported his blind mother and his sister, who was in poor health and eventually committed suicide. Baseball had no pension system and his Social Security check was insufficient. He died of a heart attack in 1968 at the age of 71.

Stan Landes pitched in the low minors in 1946 and 1947, posting a 2–2 record. When it was clear his playing days were numbered, he switched to umpiring. After a few years in the minor leagues, he made it to the majors in 1955, working until 1972. During his 18-year big-league career he umpired 2,874 regular season games, working three World Series and three All-Star Games. He was also an NBA referee. In 1964, he was elected president of the Umpires Association and for years was publicly critical of the NL’s treatment of umpires. In 1968, he complained about the players and umpires being forced to play a World Series game during a rainstorm. In 1970, he joined other umpires in picketing outside the NL playoffs in Pittsburgh. In November 1972, the day after Landes was outspoken about umpires’ low pay and working conditions at an Umpires Association meeting, he received a letter from NL President Charles Feeney firing him without providing an explanation. “He won’t answer my calls and he won’t answer my letters,” said Landes. Umpires, he noted, “are usually treated as the lowest form of labor.”82 A year later, he was working in a hardware store in Milwaukee. He died in 1994, aged 70.83

Al Forman umpired his first game in 1953, during the Korean War, while he was serving in the military in Virginia. After leaving the military the next year, he attended Fairleigh Dickinson University for two years and then completed the Al Somers Umpire School in 1956. He umpired in the minor leagues before being promoted to the majors in 1961, filling that role for the NL through 1965, when he was let go for unspecified reasons other than “we thought someone else could do a better job.”84 He continued to umpire at the college level for many years, and was hired by the AL as a “replacement”— which his colleagues called a strikebreaker—for four games when umpires went on strike in 1978 and 1979. He couldn’t make ends meet from the $30 a game he received as a college umpire so he also worked as a sales representative for a liquor company in New Jersey.85

Al Clark’s father, sports editor of the Trenton Times, raised his son as an Orthodox Jew. Al began umpiring while he was still in high school. After college, he attended umpire school and apprenticed in the minors before being promoted to the major leagues, umpiring from 1976 to 2001. He was the first umpire to wear glasses on a regular basis and one of the first AL umps to abandon using the old-style outside chest protector. In his 26-year career, he umpired 3,392 major-league games and worked two All-Star Games and two World Series. In 2001, MLB fired Clark for downgrading his first-class airline tickets to economy class and pocketing the difference. In 2004, Clark was indicted on federal mail fraud charges for participating in a scam in which baseballs were falsely authenticated as having been used in noteworthy games, inflating their value when sold to collectors. He pled guilty and was sentenced to four months in prison, followed by four months under house arrest. His memoir, Called Out but Safe: A Baseball Umpire’s Journey, was published in 2014.86

BASEBALL REBELS

Jewish players, as well as Jewish sportswriters and others, have played significant roles in challenging racial, sex, and other barriers in the sport.87

When Morrie Arnovich was inducted into the Army in 1942, he was assigned to Fort Lewis, Washington, and was named manager of the base’s team. He assembled one of the first integrated baseball teams to play on US soil since the sport was segregated in the late 1800s.88

The story of big-league pitcher Sam Nahem’s crusade to integrate overseas military baseball during World War II is ripe for a Hollywood movie. Nahem was a right-handed pitcher with left-wing politics. He may have been the only major leaguer during his day who was a member of the Communist Party. He grew up in a Syrian Jewish family in Brooklyn, was a baseball and football star at Brooklyn College, and earned a law degree during the offseasons when he was in the minor leagues. He played for the Dodgers, Cardinals, and Phillies for four seasons between 1938 and 1948. Like many other radicals in the 1930s and 1940s, Nahem believed that baseball should be racially integrated.89

During the war, the US military ran a robust baseball program at home and overseas. After Germany surrendered in May 1945, the military expanded its baseball program while American troops remained in Europe. That year, over 200,000 American soldiers—including some major leaguers—were playing baseball on military teams in France, Germany, Belgium, Austria, and Great Britain. All the teams were racially segregated.90

While serving in the Army in France, Nahem recruited players for his team, the OISE All-Stars, made up mainly of semipro, college, and former minor-league players. Nahem insisted on putting two Negro Leagues stars who were stationed in France—Leon Day and Willard Brown—on the roster, even though military baseball was officially segregated, thus fielding the overseas military’s first team known to be integrated. With Nahem pitching, playing first base, and leading the team in hitting, the OISE All-Stars advanced to the finals of the European GI World Series. In the fifth and final game, on September 8, 1945, in Nuremberg, in the same stadium where Hitler had addressed Nazi Party rallies, Nahem’s team beat a team stacked with nine major leaguers, the heavily favored 71st Infantry Red Circlers, representing General George Patton’s Third Army. Allied bombing had destroyed the city but somehow spared the stadium. The Army laid out a baseball diamond and renamed the stadium Soldiers Field.

After his playing days were over, Nahem returned to New York, where he pitched for a top semi-pro team, the Brooklyn Bushwicks, but his political activities caught the attention of the FBI, which put him under surveillance. The Cold War blacklist made it difficult for him to find or keep a job. He moved to the Bay Area, where he worked for 25 years in a Chevron chemical plant and became a union leader, even leading a strike in 1969.91

Chick Starr, the Brooklyn-born son of Jewish immigrants who had appeared in 13 games for the 1935 and 1936 Washington Nationals, headed a group that purchased the San Diego Padres in the Pacific Coast League in 1944. Four years later, as team president and general manager, he signed Negro League star John Ritchey, who became the first Black player in the PCL.92

Hank Greenberg’s experience with anti-Semitism made him sensitive to the vicious racism that Jackie Robinson faced when he broke the color barrier in 1947, Greenberg’s final season, which he spent playing for the Pirates. In May, during a game against the Dodgers in Pittsburgh, some Pirates players hurled racial slurs at Robinson from the dugout. In the first inning of the third game on May 17, Pirates pitcher Fritz Ostermueller hit Robinson on the wrist, sending the rookie to the ground, writhing in pain. In the top of the seventh inning, Robinson laid down a perfect bunt, making it difficult for Ostermueller to throw the ball to first baseman Greenberg. As he reached the base, Robinson collided with Greenberg. The next inning Greenberg was intentionally walked. When he arrived at first base, he asked Robinson, who was playing first, if he had been hurt in the earlier collision. Robinson told Greenberg that he was fine. Greenberg said, “Don’t pay any attention to these guys who are trying to make it hard for you. Stick in there. You’re doing fine. Keep your chin up.” After the game, Robinson told reporters, “Class tells. It sticks out all over Mr. Greenberg.”93

Years later, in his autobiography, Greenberg wrote: “Jackie had it tough, tougher than any ballplayer who ever lived. I happened to be a Jew, one of the few in baseball, but I was white and I didn’t have horns like some thought I did….But I identified with Jackie Robinson.94

In 1970, Robinson and Greenberg, along with journeyman pitcher-turned-writer Jim Brosnan, were the only former players who testified in court on behalf of Curt Flood’s challenge to baseball’s “reserve” clause. When Greenberg became the Cleveland Indians general manager, he refused to let the team stay in hotels that denied entry to Black players.

Seymour “Cy” Block was among a handful of players (including Danny Gardella, Tony Lupien, and Al Niemiec) who, long before Curt Flood, challenged baseball’s monopoly status and its mistreatment of players. Block and Gardella challenged the reserve clause; Lupien and Niemiec sought to regain their jobs on major-league rosters after World War II based on the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act. After serving in the military in World War II, Block returned to the Cubs for the 1945 and 1946 seasons and played in the minors until 1950. In 1951, he testified before Congress during hearings on economic concentration in major American industries, including baseball. He described the miserable pay and working conditions of minor-league players and criticized the renewal clause and baseball’s exemption from antitrust laws. After 16 days of hearings, 33 witnesses, and 1,643 pages of transcript, Congress decided to do nothing.95

Marvin Miller, the players union’s first executive director (1966–82), was baseball’s Moses, helping lead the players out of indentured servitude by modifying the renewal clause, which had bound players to teams in perpetuity. Legendary sportscaster Red Barber said that Miller, Jackie Robinson, and Babe Ruth were the most influential people in baseball history. Two years after Miller joined the union, it negotiated the first-ever collective-bargaining agreement in professional sports. Two years later, the union established players’ rights to binding arbitration over salaries and grievances. Most importantly, he led the effort to overturn the reserve clause, getting the union to support Flood’s lawsuit. After the Supreme Court ruled against Flood in 1972, Miller persuaded pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally to play the 1975 season without a contract, then file a grievance that required arbitration. The arbitrator ruled in their favor, paving the way to free agency, which allows players with sufficient seniority to choose which team they want to work for, veto proposed trades, and bargain for the best contract.

Under Miller, the union won improvements in pay, pensions, travel conditions, training and locker room facilities, and medical treatment. The owners hated the union and despised Miller. After rejecting him seven times, the Hall of Fame’s Modern Baseball Era Committee finally ended its blacklist and voted Miller in at its 2019 meeting.96 He was inducted in 2021, but the ceremony was bittersweet, because Miller had died in 2012 at age 95.97

As early as the 1930s, Jewish sportswriters were among the strongest supporters of integrating baseball. The most influential was Lester Rodney. Starting in 1936, he was the sports editor of the Daily Worker, the Communist Party’s newspaper. The paper forged an alliance with the Black press, civil rights groups, radical politicians, and left-wing labor unions to dismantle baseball’s color line.98 The protest movement published open letters to baseball owners and Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, polled white managers and players about their willingness to have Black players on major-league rosters, picketed at baseball stadiums in New York and Chicago, gathered signatures on petitions, kept the issue before the public, and put pressure on team owners. One of Rodney’s editorials attacked “every rotten Jim Crow excuse offered by the magnates for this flagrant discrimination.” When baseball executives told Rodney that Black players were not good enough to play in the majors, Rodney reported about exhibition games where Negro League players defeated teams composed of top-flight white major leaguers. He was joined in that crusade by two other Jewish Daily Worker sportswriters, Bill Mardo (birth name Bill Bloom) and Nat Low.

Shirley Povich consistently challenged baseball’s color line as a Washington Post sports columnist. Reporting from spring training in Florida in 1939, he watched several Negro League games and reminded readers that the major leagues were missing out on “a couple of million dollars’ worth of talent” by excluding Black players. In 1953, Povich kicked off a 15-part series about baseball integration called “No More Shutouts” with this lead: “Four hundred and fifty-five years after Columbus eagerly discovered America, major league baseball reluctantly discovered the American Negro.”99

Haskell Cohen, a sportswriter for the Pittsburgh Courier, a Black newspaper, and several magazines, pushed major-league teams to give tryouts to Black players to demonstrate that they were of major-league caliber. In 1942, the White Sox reluctantly invited Robinson and pitcher Nate Moreland to attend a tryout camp at Brookside Park in Pasadena, California, where the Sox were holding spring training. Manager Jimmy Dykes raved about Robinson: “He’s worth $50,000 of anybody’s money. He stole everything but my infielders’ gloves.” The two ballplayers never heard from the White Sox again. But the Pittsburgh Courier and Cohen wrote about the tryout as part of their campaign to keep the issue of baseball segregation in the public eye.100

Isadore Muchnick, a progressive Jewish member of the Boston City Council, was determined to push the Red Sox to hire Black players, even though owner Tom Yawkey had staunchly resisted integration. In 1945, Muchnick threatened to deny the team a permit to play on Sundays. Working with Pittsburgh Courier sports editor Wendell Smith and Boston Record sportswriter Dave Egan, Muchnick persuaded general manager Eddie Collins to give three Negro Leagues players—Robinson, Sam Jethroe, and Marvin Williams—a tryout at Fenway Park on April 16. During the 90-minute tryout, the three players performed well. Robinson, the most impressive of the three, hit line drives to all fields. “Bang, bang, bang; he rattled it,” Muchnick said.101 The Red Sox had no intention to hire a Black player. But after the phony tryout, Smith headed to Brooklyn to tell Dodgers president Branch Rickey—who did want to integrate his team and was looking for the right player to do it— about Robinson’s outstanding performance.

Sam Maltin, a sports columnist for the Montreal Herald and a stringer for the Pittsburgh Courier, was Robinson’s biggest booster and closest friend during his 1946 season with the Dodgers’ Montreal Royals farm team. When Robinson led the Royals to the Junior World Series championship over the Louisville Colonels of the American Association, fans surrounded him and carried him on their shoulders in celebration. In the Courier, Maltin wrote: “It was probably the only day in history that a black man ran from a white mob with love instead of lynching on its mind.”102

Once Robinson joined the Dodgers, he was still subject to a great deal of racial slurs, not only among fans, but among some sportswriters. A small number of white sportswriters, most of them Jews, embraced Robinson and wrote stories and columns supporting him and the “experiment” of desegregating baseball. They included Dick Young and Hy Turkin of the New York Daily News, Roger Kahn of the New York Herald Tribune, Joe Reichler of the Associated Press, Milton Gross of the New York Post, and Walter Winchell, an influential syndicated columnist for the New York Daily Mirror.

Although the major leagues have yet to field an openly gay player, Brad Ausmus, then a player and later a manager in the big leagues, was outspoken in support of his friend and former teammate Billy Bean when Bean came out of the closet after he’d retired from baseball.103

As manager of the Giants, Gabe Kapler was the first manager to publicly support Black Lives Matter in 2020, taking a knee on the sidelines before the start of a game and speaking out against racism.104 He was also a strong advocate for women inside and outside baseball. In 2020, he hired Alyssa Nakken, the first female uniformed coach in major-league history.105 Kapler and his wife co-founded the Gabe Kapler Foundation, which focused on educating the public about domestic violence and helping women escape abusive relationships. In 2021, he co-founded Pipeline for Change, a nonprofit dedicated to “creating opportunities and breaking down barriers for women, people of color, members of the LBGTQ community, people with physical disabilities and people from underrepresented backgrounds who seek to begin or advance a career in baseball.”106

Over 600 women played in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL), which lasted from 1943 to 1954 and was popularized by the 1992 film A League of Their Own. Four of them were known to be Jews.

Thelma “Tiby” Eisen (1922–2014) was born in Los Angeles, one of four children of David Eisen, an Austrian immigrant, and Dorothy (Shechter) Eisen, from New York City. She was already participating in semipro softball by age 14. She graduated from Belmont High School in 1941, then attended Santa Monica College part time. An outstanding all-around athlete, at 18 she played fullback in a short-lived professional football league for women in California. When the Los Angeles City Council banned tackle football for women, her team moved to Guadalajara, Mexico. After attending a tryout in Peru, Indiana, she was assigned to the Milwaukee Chicks (who soon moved to Grand Rapids) and later played outfield for the Fort Wayne Daisies and Peoria Redwings. During her AABPBL career (1944–52), she had 3,705 at-bats, a .224 batting average and 674 stolen bases, second-most in league history. Her 591 runs scored rank third. In 1946, she led the league in triples, stole 128 bases, and was selected for the All-Star team. In the winter of 1949, she toured Central America, Venezuela, and Puerto Rico with the AAGPBL.

After the AAGPBL disbanded, she played semipro softball and field hockey for California teams. She was also an outstanding golfer. She gave baseball clinics for children through a number of nonprofit organizations for many years. In 1993, she helped establish the women’s exhibit at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, and in 2004 she was inducted into the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame and Museum.107