Major League Baseball Returns to the Pacific Northwest

This article was written by Steve Friedman

This article was published in Time For Expansion Baseball (2018)

American League President Leland S. MacPhail (l.) awards the Seattle Mariners’ charter to co-owners Danny Kaye (c.) and Lester Smith. In addition to being a Hollywood star, Kaye co-owned a California-based radio network with Smith. (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

Talk of a domed stadium had begun in the 1950s. In 1957, Washington Governor Albert Rosellini said, “We in this area must have the facilities to accommodate big-time sports events, whether they be major-league baseball, professional football or championship boxing.” He added, “I immediately will explore the possibilities of what this office can do to hasten the day when such facilities can be available.”1

Dave Cohn, chairman of the board of Consolidated Restaurants and a major player in downtown politics, first proposed the idea of a domed stadium in 1950. For several years, Cohn’s idea gained little or no traction. Seattle and King County officials were acquainted with the pitfalls of asking taxpayers to underwrite the construction of a multimillion-dollar stadium. The potential of luring a major-league team to the new ballpark might not be sufficient to draw voter support. In 1960, despite a hurried and somewhat ramshackle campaign, an omnibus bill that included a $15 million stadium bond proposal almost got over the hump. More than 146,000 voters, 48.3 percent of the voting electorate, favored the measure, but 60 percent was required for approval.2

Despite this early failure at the ballot box, the need for a domed stadium had become apparent. However, local officials were focused to prepare for another major project, the Seattle World’s Fair of 1962. Any serious discussion of a domed stadium was deferred until after the fair.

By the mid-1960s, ongoing debate about the stadium had resumed, especially on its location and funding. With the success of the World’s Fair and the region’s ensuing economic boom, led by Boeing, the interest in bringing major-league sports to Seattle continued to amplify. Ongoing stadium proposals suggested multiple locations in Seattle, along with outlying cities including Tukwila and Bellevue. There even were proposals for a floating stadium situated on Elliott Bay.3 Ultimately, however, the Seattle Center location won out, primarily due to its centrality. The State Stadium Commission endorsed it in December 1968.4

By 1967, the stadium budget had risen to $40 million. To finance its construction, public funding was included under the auspices of a set of ambitious urban infrastructure and growth proposals by King County. Known as the Forward Thrust package, it consisted of sweeping locally funded improvements encompassing multiple bond proposals totaling $815.2 million that embodied transportation, community housing, water issues, and other publicly financed capital improvements, including a proposition for a multipurpose stadium.5 Voters approved a portion of the proposals, authorizing $334 million in bonds on February 13, 1968, including $40 million earmarked for the stadium.6

Despite financing approvals and the award of an expansion franchise, actual construction was delayed, as cost increases and the stadium site met public pressure. A new vote was necessary in 1970 to approve the location, which was soundly defeated.7 With the project now in jeopardy, King County Commissioners stepped up and approved an alternate King Street site, near the International District and the eventual Kingdome location.8 Finally, on November 2, 1972, King County commissioners, led by County Executive John Spellman, initiated the construction at groundbreaking ceremonies.9

The 1967 American League plan to expand was driven by its decision to let Charlie Finley’s Kansas City A’s to move to Oakland. The move left Stuart Symington, a US senator from Missouri, furious. Only after Symington threatened to attack baseball’s antitrust exemption was Kansas City awarded a replacement club. In order to maintain an even number of teams, a second franchise was added in Seattle.10 A key problem with this plan was that the new teams would begin play in 1969. This created an unrealistic timetable to prepare the team for success in Seattle.11

Knowing that this stadium funding measure was prepared for approval, the American League in 1967 awarded an expansion franchise to Seattle. As a condition, the city and county were expected to build a ballpark within three years. With the approval of the funding, via Forward Thrust, it appeared that they would meet this stipulation.

The new team, the Seattle Pilots, was underfunded and undercapitalized. Significant local support failed to materialize and the owners had to borrow heavily to keep the team afloat.12

These financial problems of the Pilots were, in many ways, the beginning of the history of the Seattle Mariners. On April 1, 1970, Federal Bankruptcy Referee Sidney Volinn declared the Pilots insolvent, just six days before Opening Day. They were free to move to Milwaukee, where a group led by automobile dealer Allan H. “Bud” Selig had become their suitor.

A few months before the Pilots departed, Washington Attorney General Slade Gorton and King County Executive John Spellman assessed Seattle’s dire baseball situation. They retained Seattle attorney William Dwyer to represent the state and county in a legal effort to keep the Pilots in Seattle.13 In creating his claim, Dwyer argued that a contract was created between the American League, on one side, and the state, county, and city – in effect, the people – on the other. He contended that the American League had violated this contract.

Dwyer further argued that the implied contract called for the American League to place and keep an expansion franchise in Seattle. In return, citizens, through their government, would fund the renovation of the aging Sicks Stadium, home of Seattle’s Pacific Coast League teams, before supporting a $40 million bond issue to fund a domed stadium. When new facility was completed, the team would move from Sicks Stadium, to become the new ballpark’s prime tenant.

In the fall of 1970, Dwyer filed a $32 million antitrust lawsuit against the American League on behalf of Washington citizens. He alleged breach of contract, fraud, and antitrust violations, even though baseball was exempt from prosecution under antitrust law.

The case did not go to trial until January of 1976. The court date was prolonged in order to afford the American League and Washington’s government entities the opportunity to reach a settlement aimed at securing a new major-league team. In 1975, a plan was hatched to move the Chicago White Sox to Seattle. The plan assumed that the White Sox’ owner, John Allyn, would sell the team to a group in Seattle, who would relocate to play in the multipurpose domed stadium under construction. To replace the White Sox, Charlie Finley would move the Oakland A’s closer to his insurance interests in Chicago.14

This prospect looked encouraging until Bill Veeck offered to purchase the White Sox to keep the team in Chicago. After the American League initially vetoed his offer, it relented and approved the purchase in December 1975.15

With confidence that major-league baseball would return to Seattle within a few years, King County continued to build the multipurpose Kingdome. However, it was not without construction woes. In January 1973, steel towers that formed the core of the stadium’s concrete piers fell on a workman and toppled other standing towers like dominoes.16 Donald M. Drake Co., the original contractor, fell behind schedule and then walked away from the project in late 1974. They claimed they weren’t being paid by King County for work beyond the original scope. The parties sued each other. Four years later, after the Kingdome had opened for events, a federal court ruled against Drake and ordered it to pony up $13 million.

Despite financial relief for the Kingdome, the judgment did not cover the increased $27 million tab over its original $40 million budget.17 Throughout the construction, local and project officials hailed the stadium for being economically sound, making it possible that corners were cut during construction to keep the project closer to budget. In the end, it is possible that this contributed to many of the later issues with the ballpark, such as roof leaks and tiles falling.18

The stadium was ready for major-league sports by 1976 and celebrated its opening on March 27. In addition to housing the Mariners, it became the home to the NFL expansion Seattle Seahawks and even hosted the NBA’s Seattle SuperSonics from 1978 through 1985.

For baseball, the Kingdome, named for the stadium’s location in King County, Washington, was an early domed stadium built with multipurpose use in mind. The publicly funded stadium ultimately cost $67 million. In the future, repairs would exceed the original construction cost.19

The ballpark offered some unique features.20 A large American flag was flown above the concrete dome. The AstroTurf carpet was rolled out by a “Rhinoceros” machine and smoothed by the “Grasshopper” machine after it had been zipped together. The stadium displayed home plate from Sicks Stadium in its Royal Brougham trophy case. For fan comfort, the stadium contained 42 air-conditioning units, 16 in fair territory and 26 in foul territory, with eight ducts in each unit. The units would blow air in toward the field, which meant fewer home runs in what would normally be a home-run hitter’s park because of its short 357-foot power alleys. For speakers located within the field of play, a ball that hit a speaker would be considered in play.

When the lawsuit commenced in 1976, the American League awarded Seattle an expansion baseball franchise in return for dropping the suit. To maintain an even number of teams, a formal expansion proceeding resulted in a second team awarded to Toronto.21

The expansion vote by the American League, conducted in advance of any settlement, was held on January 14, 1976. American League owners voted 11 to 1 to place an expansion franchise in Seattle for the 1977 season. There were two conditions: sustainable ownership and a suitable ballpark.

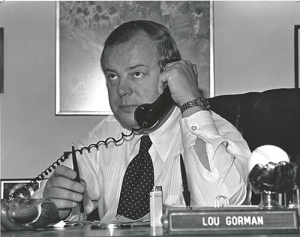

James G. “Lou” Gorman: from the Royals to the first general manager of the Mariners. (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

The formal settlement of the antitrust lawsuit, however, was not reached until February 14. The Seattle legal team argued that the plaintiffs were entitled to damages, including reimbursement of legal fees. Considering Dwyer’s success in presenting his case and the overall damages to the American League if it lost, the league caved. It agreed to pay damages to the State of Washington, King County and the City of Seattle. It marked the first time a major-league franchise had been secured through litigation.22 Sportswriter Emmett Watson of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer commented that the team should be named the Litigants instead of the Mariners.23

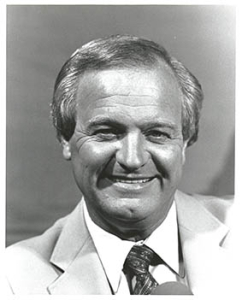

Dave Niehaus: from broadcaster of the Angels to mikeman of the Mariners – “My oh my!” (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

After the Kingdome was approved as a host venue, the American League awarded the Seattle franchise to a group of investors for $6.5 million.24 The ownership group was led by entertainer Danny Kaye, who provided most of the initial financing, and Lester Smith. Kaye and Smith had built a radio network, Kaye-Smith Enterprises. Their ventures also included a concert promotion company (Concerts West), a recording studio, a film-production company (Kaye-Smith Productions), and a radio syndication company.25 The syndicate owned several major radio stations in the Pacific Northwest, including KJR-AM in Seattle and KXL-AM in Portland.26

Other owners included Stanley Golub, a local jewelry wholesaler; Walter Schoenfeld, founder of the designer jeans company Brittania Sportswear and a founding partner of the Seattle Supersonics and the original Seattle Sounders soccer team; and James Stillwell, owner of Stillwell Construction, which was active in highway construction in the Pacific Northwest.

The formation of the Seattle Mariners was the beginning of a franchise whose general lack of success on the field has not necessarily matched its historical accomplishments. Despite never playing in a World Series, the franchise eventually generated interest beyond its accomplishments on the field. From unique plays to special players to a few exceptional seasons, the Mariners have earned attention beyond their on-field success, or lack thereof.

After the American League awarded the franchise, the ownership group set about setting up its initial management team in preparation for its first season, which was to begin in April 1977. On April 18, 1976, the team hired Lou Gorman away from the Kansas City Royals, to become its first director of baseball operations. Gorman held numerous roles with Kansas City dating back to 1968, when he served as their first scouting director. Gorman brought to the Mariners experience in building an organization from scratch.27

On June 2, the team named Dick Vertlieb as its first executive director. Vertlieb had been instrumental in the early development of the NBA’s Seattle SuperSonics and NFL’s Seattle Seahawks.

The lack of a nickname was resolved on August 24, 1976. “Mariners” was selected as the winning entry from more than 600 suggestions in a name-the-team contest. Multiple fans submitted the nickname, but the team determined that Roger Szmodis of Bellevue provided the best reason. “I’ve selected Mariners because of the natural association between the sea and Seattle and her people, who have been challenged and rewarded by it,” said Szmodis, who received two season tickets and an all-expenses-paid trip to an American League city on the West Coast.28

With their executive team hired, and a team name selected, the Mariners began to prepare their product on the field. On September 3, they hired Darrell Johnson as their first manager from a candidate pool that included Bob Lemon, Joe Altobelli, and Vern Rapp. Johnson had been fired earlier in the 1976 season after 86 games with the Boston Red Sox. His real success, however, was in leading the Red Sox to the pennant in 1975 and an exciting seven-game World Series. Despite losing to the Cincinnati Reds, Johnson was named Manager of the Year by The Sporting News.

On November 5, 1976, the Seattle Mariners and the Toronto Blue Jays held their expansion draft. Each team drafted 30 players from the other American League teams, paying a fee of $175,000 for each player drafted. Existing American League teams were allowed to protect 15 players in the first round, plus three more after each of the first three rounds (and two more players after the fourth round).29 Highlighting the Mariners selections was their first pick, outfielder Ruppert Jones of Kansas City.

The Mariners began to develop their minor-league system by participating in the 1977 amateur draft. With their first pick, they selected Dave Henderson. “Hendu” became a popular player in Seattle, playing in parts of six seasons with the Mariners before settling in Seattle after his retirement.30 Their sole minor-league franchise that year was the Bellingham Mariners of the short-season Northwest League. By 1978, their farm system had expanded to include the San Jose Missions of the Pacific Coast League and the Stockton Ports of the California League.31

Before the two drafts, the Mariners had already begun building their team as they purchased the contracts of seven players, including Dave Johnson, Jose Baez, and former Seattle Pilot Diego Segui.32

Spring-training games were played in Tempe Diablo Stadium, the same Arizona site used by the short-lived Seattle Pilots. It remained the Mariners’ site through 1993, when they moved to Peoria, Arizona, where as of 2018 they continued to conduct spring training in a facility shared with the San Diego Padres.

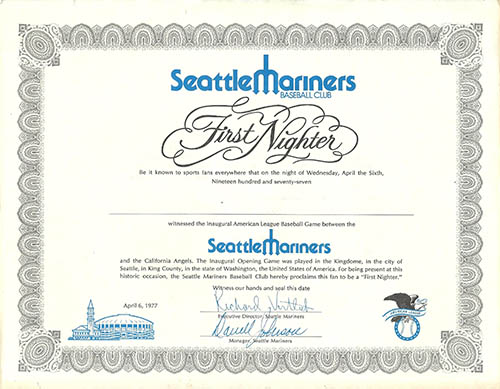

A ‘First Nighter’ certificate from the Mariners’ inaugural game at the Kingdome on April 6, 1977. A sellout crowd of 57,762 watched as the Mariners behind Diego Segui lost 7-0 to Frank Tanana and the California Angels. (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

On April 6, 1977, the Seattle Mariners played their inaugural game in the Kingdome before a sellout crowd of 57,762. The opposing team was the California Angels. The Mariners’ starting pitcher was veteran Diego Segui, who, ironically, had pitched the final inning of the final game in Pilots history.33 Segui allowed six runs in the first 3²/3 innings, and the Mariners went on to lose 7-0, the mirror-image of the Pilots’ home-debut win against Chicago eight years earlier. Despite the team’s struggles on the field, it was, at least and at last, baseball.

Leading off for the Mariners was the designated hitter Dave Collins. He was followed by Jose Baez at second base, left fielder Steve Braun, and cleanup hitter and right fielder Leroy Stanton. Bill Stein and Danny Meyer played each of the corner infield positions. Batting seventh was center fielder Ruppert Jones, followed by catcher Bob Stinson and shortstop Craig Reynolds.34

Jose Baez connected for the first hit, a single in the first inning off Frank Tanana. It was not until April 10, their fifth game, that designated hitter Juan Bernhardt hit the team’s first home run.35 The team was shut out in its first two games, but finally earned a win on April 8, defeating the Angels 7-6. For the season, the team finished 64-98. Thanks to a late-season collapse by the Oakland A’s, the Mariners finished one-half game ahead of Oakland. They drew 1,338,511 fans, an attendance total they would not exceed until 1990.

That season, the team’s offense was led by Leroy Stanton, who hit .275 with 27 home runs and 90 RBIs. The pitching was led by Glenn Abbott, who threw 204 1/3 innings and posted a 12-13 record with an ERA of 4.45.

The Mariners struggled in their early years to build a successful product. After a relatively successful first year at the gate, attendance dwindled each year under the initial ownership group and never topped 900,000 after the first year. By the end of 1980, the team was cash-strapped and weary. While accepting a 1981 award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews, Stanley Golub quipped, “When Danny Kaye and Lester Smith came to ask me to become involved in the Mariners, they said it would be a new chapter in my life. Little did I know it would be Chapter 11.”36

On January 14, 1981, California real-estate developer George Argyros agreed to purchase 90 percent of the Mariners for $10.2 million from the original ownership group. Argyros subsequently bought the other 10 percent for $2.9 million. Argyros, who had also just purchased Richard Nixon’s former Western White House in San Clemente, California, assumed the Kingdome lease after negotiating a provision that removed his personal liability for bankruptcy.37

Thus continued a period in which the Mariners struggled both on the field and at the gate. They did not post a winning season until 1991. Highly leveraged and arguably inept owners failed to build a quality organization. Only in 1992 were the Mariners sold to a strong ownership group, which consisted of Nintendo and local prominent business owners. The group saved the team from a potential relocation and eventually created a stable and strong franchise with a lasting and positive effect on the community.

STEVE FRIEDMAN has been a SABR member since 1990. He has resided in the Pacific Northwest since 1985 and has been a season ticket holder of the Seattle Mariners since 1995. His youth was spent in the San Francisco Bay Area where he followed his beloved Giants. Steve is currently retired after a career of over 35 years as an owner and operator of cable television systems.

Notes

1 Georg N. Meyers, “Build New Park or Lose out – Soriano,” Seattle Times, May 29, 1957.

2 David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman, “Wayback Machine: The Floater That Didn’t Fly,” SportspressNW.com, May 6, 2014, https://sportspressnw.com/2184239/2014/wayback-machine-the-floater-that-didnt-fly.

3 Heather MacIntosh, “Kingdome: The Controversial Birth of a Seattle Icon (1959-1976),” HistoryLink.org, March 1, 2000, https://historylink.org/File/2164.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Associated Press, “Voters in Seattle Reject Proposal,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, May 20, 1970.

8 Heather MacIntosh.

9 “Kingdome Groundbreaking and Construction,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, December 31, 2009.

10 Maury Brown, “The Team That Nearly Wasn’t: The Montreal Expos,” The Hardball Times, January 16, 2006, fangraphs.com/tht/the-team-that-nearly-wasnt-the-montreal-expos/.

11 Matt Blitz, “The Only Major League Baseball Team to Go Bankrupt: The Story of the Seattle Pilots,” Today I Found Out, September 5, 2014, todayifoundout.com/index.php/2014/09/happened-seattle-pilots/.

12 Kenneth Hogan, The 1969 Seattle Pilots: Major League Baseball’s One-Year Team (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2006).

13 David Eskanazi and Steve Rudman, “Wayback Machine: Dwyer KO’s American League,” SportsPressNW sportspressNW.com /2124781/2011, October 25, 2011.

14 John Owens, “Bill Veeck, Baseball’s Barnum,” Chicago Tribune, February 9, 2014.

15 Rob Hart, “Switching Sox: When the A’s Almost Move In,” SB Nation, November 16, 2012, southsidesox.com/2012/11/16/3649842/switching-sox.

16 Heather MacIntosh.

17 Seattle Kingdome, thisgreatgame.com/ballparks-kingdome.html.

18 Jordan Miller, “King Dome – Roof Performance Failures and Ceiling Collapse,” Pennsylvania State University 2014. failures.wikispaces.com/King+Dome+-+Roof+Performance+Failures+and+Ceiling+Collapse.

19 Ballparks.com, ballparks.com/baseball/american/kingdo.htm.

20 Ibid.

21 David Eskanazi and Steve Rudman, “Wayback Machine: Dwyer KO’s American League.”

22 Steven A. Riess, Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Clubs (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006), 802.

23 Ibid.

24 Baseball Club of Seattle LP, International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 50. (Detroit: St. James Press, 2003).

25 “Lester M. Smith Obituary,” Seattle Times, October 27, 2012.

26 History of Kaye-Smith Enterprises, kayesmith.com/about-us/history/.

27 Larry Stone and Associated Press, “Obituary/Former Mariners GM Lou Gorman,” Seattle Times April 1, 2011.

28 Associated Press, “The Mariners Chosen as Name for New Team, Eugene (Oregon) Register-Guard, August 26, 1976.

29 MLB Expansion Drafts History, baseball-reference.com/draft/1976-expansion-draft.shtml.

30 Baseball Draft Research, thebaseballcube.com/draft/research.asp.

31 Baseball Reference, baseball-reference.com/register/affiliate.cgi?id=SEA.

32 1977 Seattle Mariners Trades and Transactions, Baseball reference, baseball-reference.com/teams/SEA/1977-transactions.shtml.

33 Seattle Mariners Baseball Information Department, From the Corner of Edgar & Dave, marinersblog.mlblogs.com/on-this-date-mariners-play-inaugural-game-4984af8e53e3.

34 Seattle Mariners Baseball Information Department, On This Date: Mariners Play Inaugural Game, From the Corner of Edgar & Dave, marinersblog.mlblogs.com/on-this-date-mariners-play-inaugural-game-4984af8e53e3.

35 Seattle Mariners, Mariner Firsts. seattle.mariners.mlb.com/sea/history/club_firsts.jsp.

36 Carol Beers, “Stanley Golub, 85; Jeweler Was Part Owner of Mariners,” Seattle Times, October 10, 1998.

37 SPNW Staff, Mariners: Ownership, Organizational Timeline, sportspressnw.com/2163322/2013/mariners-ownership-organizational-timeline 9/26/13.

|

SEATTLE MARINERS EXPANSION DRAFT |

|||

|

PICK |

PLAYER |

POSITION |

FORMER TEAM |

|

1 |

Ollie Brown |

of |

San Francisco Giants |

|

2 |

Dave Giusti |

p |

St. Louis Cardinals |

|

3 |

Dick Selma |

p |

New York Mets |

|

4 |

Al Santorini |

p |

Atlanta Braves |

|

5 |

Jose Arcia |

ss |

Chicago Cubs |

|

6 |

Clay Kirby |

p |

St. Louis Cardinals |

|

7 |

Fred Kendall |

c |

Cincinnati Reds |

|

8 |

Jerry Morales |

of |

New York Mets |

|

9 |

Nate Colbert |

1b |

Houston Astros |

|

10 |

Zoilo Versalles |

ss |

Los Angeles Dodgers |

|

11 |

Frank Reberger |

p |

Chicago Cubs |

|

12 |

Jerry DaVanon |

3b |

St. Louis Cardinals |

|

13 |

Larry Stahl |

of |

New York Mets |

|

14 |

Dick Kelley |

p |

Atlanta Braves |

|

15 |

Al Ferrara |

of |

Los Angeles Dodgers |

|

16 |

Mike Corkins |

p |

San Francisco Giants |

|

17 |

Tom Dukes |

p |

Houston Astros |

|

18 |

Rick James |

p |

Chicago Cubs |

|

19 |

Tony Gonzalez |

of |

Philadelphia Phillies |

|

20 |

Dave Roberts |

p |

Pittsburgh Pirates |

|

21 |

Ivan Murrell |

of |

Houston Astros |

|

22 |

Jim Williams |

of |

Los Angeles Dodgers |

|

23 |

Billy McCool |

p |

Cincinnati Reds |

|

24 |

Roberto Pena |

2b |

Philadelphia Phillies |

|

25 |

Al McBean |

p |

Pittsburgh Pirates |

|

26 |

Rafael Robles |

ss |

San Francisco Giants |

|

27 |

Fred Katawczik |

p |

Cincinnati Reds |

|

28 |

Ron Slocum |

3b |

Pittsburgh Pirates |

|

29 |

Steve Arlin |

p |

Philadelphia Phillies |

|

30 |

Cito Gaston |

of |

Atlanta Braves |