Maris and Ruth: Was the Season Games Differential the Primary Issue?

This article was written by Brian Marshall

This article was published in Spring 2020 Baseball Research Journal

This article discusses Roger Maris’s 1961 season from a new perspective. This is not a comparison of each home run hit by Maris in 1961 with those hit by Babe Ruth in 1927, but rather proposes a method to compare the Maris performance with the Ruth performance on a near-equivalent basis. Though there exists the “low hanging fruit” of a nominal eight game difference in the two seasons, the method proposed here involves comparing the two players’ plate appearances (PA). Because each player had a large number of PA and their totals only differ by seven, the two performances can be considered essentially equivalent. This makes PA a much better number to be used for comparison purposes than the number of season games. PA is superior to at bats (AB) because it is inclusive of all appearances at the plate, therefore representing every “opportunity” to make a hit, get on base or advance a runner(s). We will discuss the infamous ruling by Ford Frick in 1961 not only because the difference in the number of season games forms the basis for the article, but also for perspective.

1927 Season Notes

On Friday, September 30, 1927, the New York Yankees played Washington at Yankee Stadium in the 154th and penultimate game of the season.1 It was a clear day with the temperature in the low to mid 80s at game time, a 3:00PM start.2 The score was tied at 2 – 2 heading into the bottom of the eighth inning, with the top of the Yankee order coming to bat. First up was the center fielder Earle Combs, who grounded out. Next up was the shortstop Mark Koenig, who tripled. The next to bat was the right fielder, George Herman “Babe” Ruth, who took his position at the plate with a reddish colored bat that was named “Beautiful Bella” and weighed about 42 ounces.3 Pitching for the Senators was the veteran Tom Zachary, who threw a first-pitch strike to Ruth. The next pitch was high for a ball. The third pitch Zachary served up was low, fast, and inside. The Babe stepped into it and Beautiful Bella met the ball with a loud crack that sent the ball into the right field bleachers about halfway up. Zachary, of course, wasn’t happy; he threw his glove to the ground in a display of anger, yelled that it was a foul ball, and argued with the umpire as Ruth slowly jogged around the bases.4 Later, in the clubhouse, Ruth shouted, “Sixty, count ’em, sixty! Let’s see some other son of a bitch match that!”5 Ruth’s 60th home run scored two runs, and the Yankees won by a score of 4 –2. That great example of five o’clock lightning set a single season record, breaking his own record of 59 set in the 1921 season.

1961 Season Notes

The 1961 season will always be remembered as the year that Roger Maris of the New York Yankees hit 61 home runs to set a new single-season home run record. It was a monumental achievement by Maris at the time—one that few, if any, would have predicted from the unassuming outfielder, and one that he would not duplicate. His previous season best was the year prior when he hit 39 homers, and his season best after 1961 was only 33. That being said, you just never know in sport when a player, or a team, can come out of nowhere and surprise everyone on a given day or in a given season. That is exactly what Maris did. To top it off, Maris was the polar opposite of Ruth both from a personality and from a career home run perspective. While Ruth relished the limelight and had 714 career home runs to his credit, Maris shied away from attention and would end his career with 275.

It was also an expansion year in the American League. The Washington Senators moved to Minnesota to become the Twins, and new franchises were formed in Washington and Los Angeles to bring the league’s team count to ten. To accommodate the additional squads, the schedule was increased to 162 games. Each AL team would play the other nine teams 18 times, nine games at home and nine games on the road, to comprise 162 games. In comparison, the 1927 New York Yankees played the other seven AL teams 22 times, 11 games at home and 11 games on the road, to make up the 154-game schedule. (The author did not compare the quality of pitchers and pitching between the 1927 and 1961 seasons as it was not part of the scope of this article.)

Frick Ruling

As the 1961 season progressed it became apparent that two New York Yankees, Maris and Mickey Mantle, were going to go head to head for the home run title, not just for that season, but for all time. The Maris/Mantle home run battle and the nominal eight game differential stimulated MLB Commissioner Ford C. Frick to make the following ruling on July 17, 1961:

Any player who may hit more than sixty home runs during his club’s first 154 games would be recognized as having established a new record. However if the player does not hit more than sixty until after his club has played 154 games, there would have to be some distinctive mark in the record books to show that Babe Ruth’s record was set under a 154-game schedule and the total of more than sixty was compiled while a 162-game schedule was in effect.6

There were two problems, and one issue, with the Frick ruling that apparently were unbeknownst to him at the time of the ruling. The first major problem was that the wording “some distinctive mark” did not define what the distinctive mark would be, leaving it open to interpretation. That is exactly what the media did; they interpreted the “distinctive mark” wording to mean an asterisk, as the following quotation states:

FORD FRICK, the baseball commissioner, ruled rightly when he decreed that no successor to Ruth would be recognized unless he hit 60 or more homers within the 154-game schedule on which the Babe operated. The new 162-game schedule would offer too great a target. Frick has added that any man who surpassed Ruth’s 60 in the added eight games, would have to be content with entry in the record book under an asterisk.7

The second major problem with the Frick ruling was that he created a situation where the fans would be focused on the first 154 games with great anticipation and meaning and the remaining eight games would effectively be rendered less meaningful. That situation wasn’t owner-friendly or good for business, as owner Bill Veeck put it: “What he did, in that one brilliant stroke, was build the interest up to that 154th game and throw the final eight games out in the wash with the baby. What he did was to turn what should have been a thrilling cliff-hanger lasting over the full final week of the season into a crashing anti-climax.”8

Then there was the issue that Frick considered himself a friend of Ruth’s. As a sportswriter for the William Randolph Hearst-owned New York American newspaper, Frick had covered the New York Yankees beginning in 1922.9 He had also been a ghost writer for Babe Ruth’s newspaper columns.10 The Los Angeles Times lampooned Frick’s friendship with Ruth and its relationship to the matter of the asterisk as follows:

Once upon a time there was this nice man. His name was Ford Frick and he was president of the National League which was a nice job because all he had to do was what Branch Rickey told him.

One day a committee came to him and said “How would you like to be Czar of all baseball?”

So they made him Czar of all baseball ….

And one day the Czar said, “Look can’t I do ANYTHING around here?!” and his subjects said “Sure!’ You can call off any World Series where the field is wet enough, Just check with Walter O’Malley first.” And he said, “I don’t mean THAT! Anybody knows enough to come in out of the rain. I want to do something about baseball!” This puzzled them.

“What do you want to do?” they asked suspiciously. “I want to put an asterisk after Roger Maris’ name!” he screamed. “After all, Babe Ruth was a friend of mine!”11

Analysis

Using the number of scheduled games as the standard to evaluate the legitimacy of Maris’s home-run record may have been the perceived best approach at the time but was it? Although there is an eight-game differential in Maris’ favor, the number of games do not necessarily equate to opportunity. Did Maris have five percent more opportunity than Ruth? To compare the Maris in 1961 and Ruth in 1927 performances on a more equivalent basis it becomes necessary to use a metric with a lower degree of variation: plate appearances.

PA is the sum of a player’s at-bats (AB), walks (BB), sacrifice hits (SH), sacrifice flies (SF), reached base on interference, and being hit by a pitch (HBP). The PA totals for Maris in 1961 and Ruth in 1927 were nearly equal, differing by only seven, or a differential of a mere one percent (see Table 1 below).

|

Table 1. Determination of PA |

||

|

Metric |

Babe Ruth 1927 |

Roger Maris 1961 |

|

AB |

540 |

590 |

|

BB |

137 |

94 |

|

HBP |

0 |

7 |

|

SH |

14 |

0 |

|

SF |

0 |

7 |

|

PA |

691 |

698 |

|

PA Difference = 7 |

||

Table 1 indicates that the HBP, SH, and SF can effectively be negated with respect to the two players since the sum of the three metrics in each case is 14 which results in a difference between the two amounting to the BB differential. The plate opportunity ceases to be a true hitting opportunity if the batter is intentionally walked. Both Ruth in 1927 and Maris in 1961 typically batted third, so a pitcher had to pick his poison. In the case of the 1927 Yankees, the pitcher could chose to walk Ruth and face Lou Gehrig, and in 1961 the pitcher had a choice between Maris and Mantle. Ruth was in fact walked 43 more times than Maris.

Maris’s final three home runs were hit after the 154th game, but for each of home runs number 59 and 60, Maris hit them when he’d had fewer PA than Ruth (see Table 2 below).

|

Table 2. Home Runs With Respect to Game Number and PA Number |

||||||

|

Player |

||||||

|

Babe Ruth |

Roger Maris |

|||||

|

HR # |

Date |

Game # |

PA # |

Date |

Game # |

PA # |

|

58 |

9/29/27 |

153 |

679 |

9/17/61 |

152 |

655 |

|

59 |

9/29/27 |

153 |

682 |

9/20/61 |

155 |

666 |

|

60 |

9/30/27 |

154 |

687 |

9/26/61 |

159 |

684 |

|

61 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

10/1/61 |

163 |

696 |

|

N/A = Not Applicable |

||||||

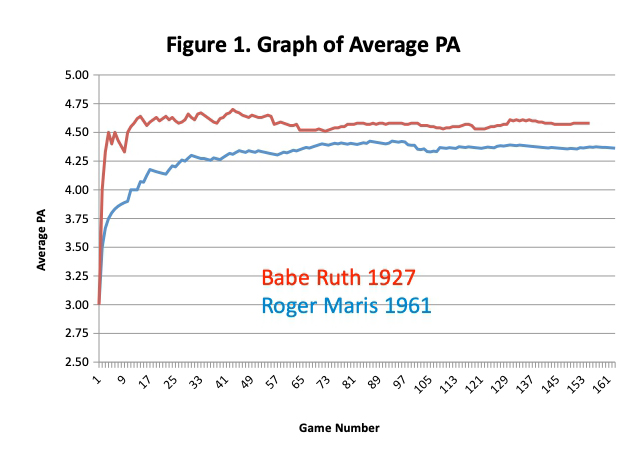

Regarding the famous number 60 home run hit by Ruth, it was during game number 154 and PA #687 while the 60th home run hit by Maris was during game number 159 and PA #684. Maris hit his 60th home run five games later than Ruth hit his 60th home run but Maris managed to do it a full three plate appearances ahead of Ruth. This fact clearly indicates that the Game Number wasn’t as key as it was perceived to be during the 1961 season. The graphs of the Average PA for both Ruth and Maris, over the course of the respective seasons, is depicted in Figure 1. It is clear that the two graphs are distinct in that they do not touch at any point other than for the first game of the season, nor do they cross at any point. It is also clear that the average PA for Babe Ruth is greater than that for Roger Maris throughout the whole season.

Figure 1. Graph of Average PA

The ratios of PA/GP (Games Played) and PA/HR (Home Runs) are displayed in Table 3, showing that those for Maris are less than Ruth’s. Maris had less opportunity on a per-game basis than Ruth, and on average hit a home run per slightly fewer plate appearances. The PA/GP are those depicted in Figure 1 as the final values for each of Ruth and Maris. Even though Maris played in more games and had seven more PAs, his PA/GP ratio was lower than Ruth’s over the course of the season. It is for this reason that it can be said that Ruth had more opportunities, on average, per game.

|

Table 3. Determination of Player PA Ratios |

|||||

|

Player |

GP |

HR |

PA |

PA/GP |

PA/HR |

|

Babe Ruth |

151 |

60 |

691 |

4.58 |

11.52 |

|

Roger Maris |

160 |

61 |

698 |

4.36 |

11.44 |

The raw data for Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 1 were derived from the Baseball-Reference.com web site, specifically the team batting table on the team pages, the standard batting table on the player pages, the game-by-game logs on the game log pages, and the play-by-play table on the game boxscore pages.12 The PA/GP listed in Table 3 are those depicted in Figure 1 as the final values for each of Ruth and Maris.13

Table 3 states that the number of games played by Maris in 1961 was 160, while Maris’s Baseball Reference page lists him as playing in 161 games. There were three games during the 1961 season that Maris did not record any PA: May 22, July 29, and September 27. Maris was in the lineup for the May 22 game at Yankee Stadium, and took his position in right field, but he came out due to an eye irritation.14 (Yogi Berra, who had been behind the plate, went to right field and Johnny Blanchard went in to replace Berra as catcher.) Maris was only in the game for a few minutes during the top of the first inning, and never made a plate appearance in the game. For the game on July 29, Maris was never in the lineup because he was sidelined with a pulled muscle in his left leg.15 (Berra again played right field.) On September 27, Maris was given the day off as detailed in The New York Times: “Maris, who had hit his sixtieth homer on Tuesday night, said he was ‘too bushed’ to play. When Roger asked permission to skip yesterday’s game, manager Ralph Houk readily consented.”16

The End of the Season: No Asterisk

When the final official AL batting statistics were released for publication by MLB on December 17, 1961, there was no asterisk, nor any other mark/indication, associated with Maris’s statistics. John Drebinger pointed out in The New York Times, that there wasn’t any “star, asterisk or footnote attached to the listing” of the notation that Maris had set a record for hitting the most home runs in a single season.17 Remember that at the time when Maris hit his 59th home run, the asterisk had seemed assured, as evidenced by this September 21 Times article, whose headline blared Maris was “resigned” to the mark:

Maris, surrounded and half-pinned to the dressing room wall at Memorial Stadium, even conceded to Commissioner Ford Frick’s asterisk.

The commissioner, it will be recalled had ruled that if Maris was to match or break Babe Ruth’s record of sixty homers in a season, he would have to do it within a 154 games. Any mark beyond that, Frick insisted, would get an asterisk in the record book.18

Frick maintained that he never stated there should be an asterisk, saying: “As for that star or asterisk business, I don’t know how that cropped up or was attributed to me, because I never said it.”19

Frick effectively was his own worst enemy in the asterisk matter. However, after all the dust had settled, the official AL statistics didn’t include a mark beside Maris’s feat. Down the road, any baseball historian or researcher would know and understand there was a difference in the number of AL games in the 1927 and 1961 seasons because it is low-hanging fruit. The riper fruit is the fact that Maris in 1961 had more PA over the course of the season than did Ruth in 1927, not to mention hit his record tying 60th home run in three fewer PAs than Ruth.

Conclusions

The thought of employing an asterisk, or any other mark, in the record book solely based on the difference in the number scheduled regular season games was not the proper approach for Maris’s 1961 accomplishment. The number of games doesn’t necessarily equate to the degree of opportunity. Frick was too close to the situation due to his past affiliation with Ruth and may have been influenced by his personal feelings to a degree when he made his ruling, although I don’t doubt that he felt he had the best interest of MLB in mind. He could have waited until the end of the season and made a decision after he had a chance to review all the statistics and the matter in detail.

Both the 1927 and the 1961 seasons were similar, from a team perspective, in that both teams won their respective pennants and won the World Series. The New York Yankees of 1927 were arguable one of the greatest teams in MLB history with a season record of 110 wins, 44 losses, and one tie. The New York Yankees of 1961 had a record of 109 wins, 53 losses, and one tie. Ruth in 1927 was involved in a home run race with his teammate Gehrig much like Maris in 1961 was with Mantle.

Both Ruth and Maris were similar from a player perspective in that they both batted left, played right field, and typically batted in the third position of the batting order,. They also both typically hit their home runs in Yankee Stadium into the infamous “short porch” down the first-base line (and both hit more home runs on the road than at home).

On the surface, it appeared to be a no-brainer that Maris would have more opportunity to accomplish his feat than Ruth did to accomplish his. The fact is that Maris actually had less opportunity on a per game basis. This doesn’t mean to imply that Maris was better than Ruth as a player or from a hitting perspective, but it does say that Maris in 1961 edged out Ruth in 1927, not merely in total number of home runs hit, but from a PA perspective as it relates to when a number of his HRs were hit. In summary:

a) The number of scheduled games for differed by 8, a 5% differential.

b) The PAs for Maris are 698 and for Ruth are 691, a difference of 7, a 1% differential.

c) Maris had a lower Average PA/GP throughout the whole of the season.

d) Maris had a lower PA/HR.

e) Maris hit his 60th in PA #684 and Ruth hit his 60th HR in PA #687.

While the number of games can be greater, it doesn’t necessarily equate to more opportunity. It is the opportunity that must be equal, or near equal, for the performances to be considered equivalent. Then a suitable comparison can be made.

BRIAN MARSHALL is an Electrical Engineering Technologist living in Barrie, Ontario, Canada and a long time researcher in various fields including entomology, power electronic engineering, NFL, Canadian Football and MLB. Brian has written many articles, winning awards for two of them, and two books in his 60 years with two baseball books on the way, one on the 1927 New York Yankees and the other on the 1897 Baltimore Orioles. Brian has been a SABR member for three years and is a long time member of the PFRA. Growing up Brian played many sports including football, rugby, hockey, baseball along with participating in power lifting and arm wrestling events, and aspired to be a professional football player but when that didn’t materialize he focused on Rugby Union and played off and on for 17 seasons in the “front row.”

Notes

1 The New York Yankees actually played 155 games in the 1927 season because there was a make-up game for the April 14 game with the Philadelphia Athletics that was tied after ten innings when the game was called due to darkness.

2 “The Weather,” The New York Times, October 1, 1927, 39.

3 Harvey Frommer, Five O’Clock Lightning: Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and the Greatest Team in Baseball, the 1927 New York Yankees. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008, 145.

4 “Ruth Crushes 60th to Set New Record: Babe Makes it a Real Field Day by Accounting for All Runs in 4-2 Victory,” The New York Times, October 1, 1927, 12.

5 Robert W. Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life. (The Penguin Sports Library, General Editor, Dick Schaap.) New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1986, 309.

6 “Ruth’s Record Can Be Broken Only in 154 Games, Frick Rules,” The New York Times, July 18, 1961, 20.

7 “This Morning with Shirley Povich: Mantle has Rare Chance to Beat Ruth’s 60,” The Washington Post, July 25, 1961, A14.

8 “Commissioner Just a Traffic Cop to Veeck: Frick’s ‘Asterisk’ Ruling on Maris Enough to Give Master Promoter Apoplexy,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 25, 1962, Part 4, 4.

9 “Ford Frick,” Wikipedia, accessed September 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ford_Frick

10 Warren Corbett, “Ford Frick,” SABR Baseball BioProject, accessed September 2019. https://sabr.org/node/41789

11 Jim Murray, “A Czar is Born,” Los Angeles Times, December 17, 1964, Part III, 2.

12 Standard batting tables from the player pages for Babe Ruth and Roger Maris on Baseball-Reference.com, accessed in September 2019. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/r/ruthba01.shtml and https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/m/marisro01.shtml

13 The author compiled a separate table for each of Babe Ruth and Roger Maris that calculated the PA on a game-by-game basis then summed the PAs over the course of the season. Then for each of the games Ruth and/or Maris hit a home run the author documented the outcome for each individual PA during the game and numbered them incrementally. The author used the “Play by Play” information provided on Baseball-Reference.com to obtain the “outcome” information for each of the PAs. Naturally, the final PA numerical number had to match PA total listed for each of Ruth and Maris. The purpose of creating the individual PA Tables was to have a means to both identify and to “look up” an individual PA and associate it with a given home run and/or outcome for each of the games Ruth and/or Maris hit a home run. Baseball-Reference.com was accessed a number of times during the month of September 2019.

14 John Drebinger, “Yanks Overwelm Orioles After Being Retired in Order for First Five Innings,” The New York Times, May 23, 1961, 50.

15 “Yanks Edge Birds, 5-4, On Berra’s Homer in Eighth,” The Baltimore Sunday Sun, July 30, 1961, Sports section, 1.

16 John Drebinger, “Orioles Turn Back Yanks on Barber’s Pitching and Gentile’s 46th Homer,” The New York Times, September 28, 1961, 52. The Yankees technically played 163 games in the season, as the second game of the doubleheader played on April 22 was called on account of rain when the score was tied. The game itself was replayed from the beginning as part of another doubleheader on September 19. The April game did not factor in the standings, but the personal statistics for the players in that rained-out contest did count.

17 John Drebinger, “Record of Maris Has No Asterisk,” The New York Times, December 23, 1961, 18.

18 Louis Effrat, “Maris is Resigned to * in the Record Books: * Will Mean Record Was Set After 154 Games,” The New York Times, September 21, 1961, 42.

19 “No * Will Mar Homer Records, Says Frick With †† for Critics: If Maris Surpasses Ruth 60, Feat Will Get Full Credit as 162-Game Standard,” The New York Times, September 22, 1961, 38.