Marvin Miller and the Birth of the MLBPA

This article was written by Michael Haupert

This article was published in Spring 2017 Baseball Research Journal

“The unionization of professional athletes has been the most important labor relations development in professional sports since their inception.”1

Journalist Studs Terkel called Marvin Miller “the most effective union organizer since John L. Lewis,” long-time president of the United Mine Workers and founder of the Congress of Industrial Organizations.2 Actually, he may have sold Miller short. Miller took over a moribund group of what he considered among the most exploited workers in the country, while at the same time being irreplaceable in their work, and turned them into arguably the most powerful labor union in American history.3 Last year marked fifty years since Marvin Miller’s arrival on the baseball scene, and this is the story of how it happened.

Journalist Studs Terkel called Marvin Miller “the most effective union organizer since John L. Lewis,” long-time president of the United Mine Workers and founder of the Congress of Industrial Organizations.2 Actually, he may have sold Miller short. Miller took over a moribund group of what he considered among the most exploited workers in the country, while at the same time being irreplaceable in their work, and turned them into arguably the most powerful labor union in American history.3 Last year marked fifty years since Marvin Miller’s arrival on the baseball scene, and this is the story of how it happened.

Marvin Julian Miller was born April 14, 1917, in the Bronx. He was the first child of Alexander and Gertrude Wald Miller.4 Shortly after his birth, his parents moved to Brooklyn, thus Miller grew up rooting for the Dodgers. Young Marvin was inculcated in the importance of unions at an early age. He walked a picket line with his father—a clothing salesman—and his mother was active in the New York City teacher’s union. He graduated with a degree in economics from New York University in 1938. Prior to taking over the leadership of the MLBPA, he worked for the National War Labor Board, the International Association of Machinists, the United Auto Workers (UAW), and the United Steelworkers of America (USWA).

Miller cut his teeth on union issues while working for the USWA. He joined them as a staff economist in the research department in 1950, ultimately rising to chief economist and assistant to the president. In those roles he also served as a member of the union’s basic negotiating committee—the front lines of labor negotiations that would steel him (pun intended) for his future work in baseball. In 1950 the USWA, along with the UAW, were considered the twin pillars of American union strength. USWA membership exceeded a million in the first half of the 1950s, and the USWA had more than 2,300 locals throughout North America.5 By the time he took over the MLBPA, his negotiating skills were finely honed and his devotion to labor causes was well established. When he first arrived on the baseball scene he was an unknown to the general public, but in labor circles his skills were well respected.

Miller’s path to baseball began unexpectedly. In early 1965 the USWA concluded a bitter presidential election that resulted in the ouster of David McDonald, Miller’s boss and mentor. The shake-up led Miller to begin looking for alternate employment. After exploring opportunities with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a faculty position at Harvard, he was asked to interview for the executive directorship of the MLBPA. Miller was unenthusiastic about the position, but when he learned that Robin Roberts was heading the search committee, he agreed to an interview out of deference to Roberts’s heroic on-field accomplishments.

When asked later in life how he could have turned down a position at Harvard for the fledgling ballplayers union, Miller explained that he thought academic jobs were likely to come along again, but the chance to build a union was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. In addition, he reasoned that because the MLBPA was totally ineffective, anything he did would be a big improvement. He loved baseball and a good fight, so it seemed like a natural fit.6

PLAYER UNIONS BEFORE THE MLBPA

The MLBPA was the fifth attempt by ballplayers to organize themselves. Until the introduction of the reserve rule prior to the 1880 season, players could shop their services to multiple teams. The reserve rule, however, altered the labor market, tipping the salary negotiation scales heavily in management’s favor. This certainly did not go unnoticed by the players, and just five years later they made their first attempt to level the playing field with the formation of the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players in 1885. The Brotherhood eventually created its own league, the Players League, which collapsed—taking the Brotherhood down with it—after its only season in 1890.

The next attempt at unionization occurred during the heat of the National League war with the upstart American League. The Protective Association of Professional Baseball Players had a brief run, but faded into insignificance when the leagues settled their differences. Attorney David Fultz then established the Baseball Players Fraternity in 1912 and it survived until 1918, after which he accepted the presidency of the International League. In 1946 the short-lived American Baseball Guild was organized by Robert Murphy, a Boston attorney. It lasted one year, and is perhaps most famous for an aborted mid-season strike by the Pittsburgh Pirates. Murphy’s lasting legacy is a spring training per diem for players, known to this day as “Murphy money.”

Though Murphy and the Guild quickly disappeared, his efforts spurred some changes. In an effort to ward off any future attempts to unionize, the owners worked with a player representative from each team and established a minimum salary of $5,000 with a maximum salary reduction of 25% from one year to the next. The biggest prize in the eyes of the players was the creation of a pension. It was originally funded by player contributions and proceeds from the sale of World Series radio and television rights. Eventually revenues from the All-Star game became a central source of pension funds. The players took the pension plan very seriously, but it was not well funded, and by 1949 was nearly insolvent.7

THE FORMATION OF THE MLBPA

The underfunded pension became the grain of sand that irritated the players into action. It might have been the most important thing that ultimately led to the hiring of Miller. In 1953 players began to question the fund, wanting more information and the ability to monitor it. Management stonewalled this request, but eventually agreed to meet with the players on the issue. Each club selected a player representative to do so, but there was no formal organization in place that could take action.

In August 1953 the player reps took matters into their own hands and hired attorney Jonas Norman Lewis to serve as their liaison with the owners at the pension committee meeting. Lewis had been with a law firm that represented the New York Giants for many years, and one of his clients was the Harry Stevens concession firm. His selection was an indication of the naiveté of the players in all matters legal. In an April 1954 article in the Labor Law Journal Lewis described himself as “a lawyer primarily interested in labor cases from management’s side,” and opined that strikes were an unfair labor practice. He defended baseball’s reserve system and the antitrust exemption baseball enjoyed, as well as expressing the opinion that ballplayers should feel lucky to have their jobs and enviable wages.8 Walter O’Malley, who abhorred the very idea of a players union, reminded Lewis that he was an “owners’ man,” and tried in vain to talk him out of accepting the position.9

When Lewis arrived for the meetings the owners refused to allow him in the room. Over the next few years the players kept him on retainer and turned to him for advice on various issues. Despite his background, Lewis fought hard for the ballplayers.

In December 1953, while the owners held their winter meetings in Atlanta, the players gathered there as well—though separate from the owners—and formed the Major League Baseball Players Association, chartered in New York. Lewis filed the paperwork and Bob Feller was elected the first president of the MLBPA, holding the position until 1959.

Though Lewis was devoted to the players, he was not a full-time employee and resisted becoming one. As a result there was no central office, offseason communication was sparse, and the MLBPA languished. While Lewis was committed to the players, he did not feel they reciprocated that commitment to their own cause, citing their reluctance to pay union dues. The players fired Lewis in February 1959, grousing about his lack of commitment to their cause and complaining that he refused to tour the spring training camps to meet with them.10

Later that year Feller stepped down, and the association hired Frank Scott on a part-time basis as executive director to oversee the organization’s trivial operations. Scott had previously served as the traveling secretary for the Yankees. He developed relationships with many players in that role, and after leaving, he served as a go-between, an early iteration of an agent, for some of them to secure endorsements and paid guest appearances.

Scott proposed that the players create a central office for their association, staffed by a full-time position that he would fill. The players agreed and Scott set up headquarters in a New York hotel where he also ran his agent business. For the first time, the players saw an active role for themselves, describing the purpose of the central office as an instrument for ballplayers to register their views and opinions on matters pertaining to Association policy or player welfare. Scott’s first major initiative was to hire a legal advisor. The players stated that their most pressing interests in the new attorney were to protect the pension and give them a voice in complaining about playing conditions. Judge Robert C. Cannon got the job ahead of a list of candidates that included former commissioner Happy Chandler, future owner Edward Bennett Williams, and Richard Moss, the man who would hold the position under Marvin Miller.

JUDGE CANNON

Cannon certainly had the pedigree for the job. His father, an attorney, once represented Shoeless Joe Jackson, and had previously attempted to unionize the players. The younger Cannon was strongly advocated for by Bob Friend, the influential Pirates player rep. However, he was another hire that exposed the players’ weak grasp of labor relations. Upon his appointment, Cannon voiced with pleasure that he was well received by baseball authorities and club owners. He also admitted in his application that he was not an authority on pensions, but espoused his belief that baseball was an important influence on American youth and as a result players should set a good example on and off the field. At one meeting with owners he told them his “primary concern will be what’s in the best interest of baseball. Second thought will be what’s best for the players.”11

Cannon was actually more interested in leading the owners than he was in representing the players. He coveted the commissionership. In positioning himself for the job, he once described Ford Frick as “a good man . . . [who] did not have the training to be commissioner.”12 He felt that a judicial background was necessary to be a successful commissioner, along with a love of baseball—a description of his own qualifications. When Frick retired in 1965, Cannon, still serving as legal advisor to the players, launched an unsuccessful bid for his office. Instead, the owners chose retired Air Force General Spike Eckert. Cannon’s interest in the commissionership should have sounded alarm bells with the players, but they believed his cozy relationship with ownership was an asset to their cause.

ELECTING A NEW LEADER

Pensions, not salaries, were the primary concern of the players in 1965. By then the MLB pension fund was accruing $1.6 million per year. Each player was making an annual contribution of $344 with teams contributing 95 percent of the All Star Game’s ticket revenue (a game in which the players participated for free) and 40 percent of the broadcast fees from the All Star and World Series games.13 Robin Roberts and Jim Bunning, two of the more vocal player reps, voiced a suspicion shared by many that the owners were under-valuing the media revenues in order to reduce their pension obligations to players. This was easy enough to do since the rights were sold as a package, bundled with the Game of the Week broadcasts. The players felt overmatched. Ralph Kiner argued that ballplayers needed legal representation because they were “the worst businessmen in the land.”14 Dodgers outfielder Al Ferrara was more blunt, noting that the players “were getting screwed by all kinds of people.”15 The players needed some legal muscle because the owners were evasive about the pension, evading player questions about its operation and steadfastly refusing to open the books for the players to examine. The seeds of distrust between players and management were sown long before Marvin Miller arrived on the scene.

Pensions, not salaries, were the primary concern of the players in 1965. By then the MLB pension fund was accruing $1.6 million per year. Each player was making an annual contribution of $344 with teams contributing 95 percent of the All Star Game’s ticket revenue (a game in which the players participated for free) and 40 percent of the broadcast fees from the All Star and World Series games.13 Robin Roberts and Jim Bunning, two of the more vocal player reps, voiced a suspicion shared by many that the owners were under-valuing the media revenues in order to reduce their pension obligations to players. This was easy enough to do since the rights were sold as a package, bundled with the Game of the Week broadcasts. The players felt overmatched. Ralph Kiner argued that ballplayers needed legal representation because they were “the worst businessmen in the land.”14 Dodgers outfielder Al Ferrara was more blunt, noting that the players “were getting screwed by all kinds of people.”15 The players needed some legal muscle because the owners were evasive about the pension, evading player questions about its operation and steadfastly refusing to open the books for the players to examine. The seeds of distrust between players and management were sown long before Marvin Miller arrived on the scene.

But the search for a full-time leader was complicated by the underlying hostility that ballplayers had toward unions as a result of a very effective propaganda campaign run by the owners and fostered by the press. Players had been taught that baseball was a game, not a business; the owners were sportsmen, not businessmen; the commissioner was there to serve the game, not the owners (by whom he was hired and to whom he answered). The party line was that players should feel privileged to be able to play for a living while the average American had to work for a living. Unions, they were reminded, meant work stoppages, mafia involvement, and violence. The most important issue in that list was work stoppage. No work meant no pay, and few players could afford to miss a paycheck.

Miller was approached about interviewing for the baseball job by George Taylor, a professor at the Wharton School of Business, and a well-known labor advisor. Taylor, who was assisting the MLBPA in identifying potential leaders, had originally approached Lane Kirkland, a high ranking official (and eventual president) of the AFL-CIO, but had been rebuffed. Miller was his second choice, but a solid one, given his background and accomplishments with the steelworkers.

The search committee consisted of Roberts, Bunning, Harvey Kuenn, and Bob Friend. The other candidates interviewed for the job included Judge Cannon (Friend’s favorite—so much so that he didn’t even bother interviewing Miller), Detroit attorney Tom Costello (Bunning’s early choice), and Bob Feller, who actively campaigned for the job. Others known to be considered for the job were Hank Greenberg and Giants Vice President Chub Feeney.16

Miller nearly sabotaged his own candidacy. During the interview he strongly argued against the suggestion that his legal advisor might be former Vice President Richard Nixon. He told the players that because the MLBPA was a small organization, it could not afford any incompatibility in a union with just two professionals. He urged them to let their director, whoever that may be, pick his own legal counsel.

After meeting with the committee, Miller developed a strong desire for the job. He wrote to Roberts expressing his interest, highlighting the near perfect fit between the players’ needs and his skills. He sought to soothe the fear that a labor leader like himself would bring teamster tactics and mafia connections to the game by convincing Roberts that harmonious relationships between players and owners must prevail without any sacrifice of player interests.

Despite Miller’s outstanding credentials, the committee recommended Judge Cannon, and in January of 1966 at a player rep meeting overseen by Commissioner Eckert and his aide Lee MacPhail, the nomination was seconded, and on the second ballot he was unanimously recommended. All that remained was a pro forma vote of the rank and file. Ten days later, before his election could be held, his swift unraveling began.

Cannon had campaigned for the position, but then had second thoughts when he realized how much money he would lose in his foregone judicial pension if he switched jobs. Instead of turning down the job, he sought to renegotiate the contract, asking for a raise to cover his lost pension, and resisting the requirement that he relocate to New York.

In a sign of how interested the owners were in seeing Cannon take the position, Pirates owner John Galbreath offered to reimburse his lost pension. Cannon refused the offer, claiming to have lost interest in the position because he had “got it up to here with players who kept talking about money.”17 That was certainly the pot calling the kettle black. And it was a lucky break for the players.

The players—including Friend—were turned off by what they viewed as blatant greed and withdrew the offer. With tail between their legs they turned to Miller, who, with wounded pride, initially rebuffed them. After intense personal lobbying by Roberts and a humbled Bob Friend, he ultimately agreed to take the position if the players elected him.

The process, however, did not go smoothly. Judge Cannon and MLB executives were actively working behind the scenes to quash Miller’s election. While the players may have been reticent about hiring a labor leader, the owners were downright mortified at the idea. The last thing they wanted was an experienced, skilled, and knowledgeable adversary across the table from them. Naturally, they preferred things the way they used to be, without any organization on the part of the players. But if they had to negotiate with a players union, far better that it be led by a friendly face like Judge Cannon.

The owners quickly acted to discredit Miller. Before he even had a single meeting with the rank and file, newspaper articles appeared quoting players antagonistic to the idea of a professional labor man leading their association. They relied on heavy doses of anti-union propaganda to sway the players, and inserted coaches and managers into the meetings with Miller to both spy and intimidate.

The players were afraid that if they unionized Miller would lead them out on strike. They had been brainwashed by MLB executives that this was the inevitable outcome of a Miller leadership and unionization, stoking fears that only a few well paid superstars could financially weather any kind of walkout.18

Miller’s first meeting was with the Angels at their spring training site in Palm Springs. After a brief presentation he received the silent treatment. He only got a response, and a tepid one at that, after pointing out that because their pension plan had not kept up with inflation it had actually eroded in value.

From Palm Springs, he headed to Arizona to meet with the Giants, Cubs and Indians, and received an equally unenthusiastic reception. Miller was not informed of the vote totals at the time, which was probably good, since the players in the Cactus League opposed him overwhelmingly (102-17). The Giants were unanimous in their rejection of his nomination.19

The owners’ smear campaign was effective in the western camps, but failed in the east when they overplayed their hand. The day before Miller met with the Dodgers in Vero Beach, Buzzie Bavasi visited the clubhouse. He warned the players that they should be afraid of unions, reminding them they had families to feed, and unions meant strikes, which meant no work and no paycheck. Cannon was also deployed, distributing pamphlets to every clubhouse warning the players against hiring a labor man who would bring racketeering and goon squads to the game. The approach backfired. The players concluded that if ownership was so against the union, it must be good for the players.

By pointing out that by legal definition the players were already a union, despite their name—Major League Baseball Players Association—Miller was able to assuage their fears. While he did not promise that he would never lead them on strike, he did emphasize that the players would set the tone and enumerated the advantages of a well-timed strike if the stakes were worthwhile. Finally, he implored them to become active in their association so that they, and not he, would dictate its direction and the issues they wanted to address.

In the western camps the votes were conducted publicly by managers. In Florida the player reps took control and saw to it that the players ran the elections, conducted as secret ballots. The difference was staggering. In the east Miller was supported by a vote of 472-34.

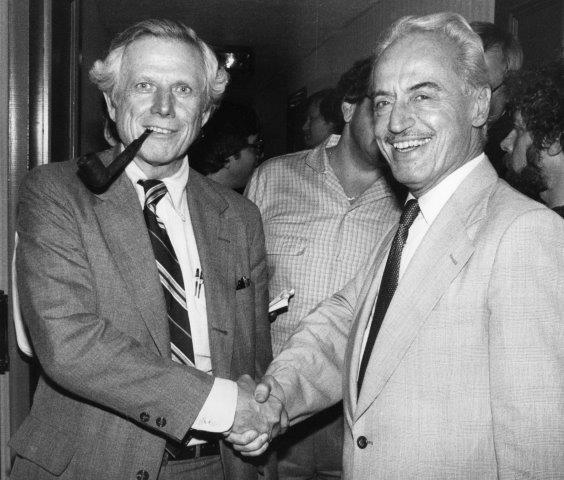

Baseball would never be the same. On April 12, 1966, the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) announced the second executive director of what had been, up to that point, a largely ineffective association. Miller was about to change that.

THE FIRST HURDLE

Having failed in their attempt to prevent Miller’s election, the owners changed strategy, attacking on two fronts. While he may have been elected, Miller was not yet under contract, a situation they sought to exploit. Additionally, the owners had intimate knowledge of MLBPA finances, especially their weaknesses. Once again they deployed Judge Cannon.

The Judge was assigned to draft the newly elected executive director’s contract. On its face, this seemed reasonable, since he was the legal counsel for the MLBPA. However, he was also the jilted suitor whose real desires lay in serving the owners. Not surprisingly then, the contract Cannon originally produced was refused by Miller.

Miller and the players had agreed on a five-year deal with a July 1, 1966, start date at $50,000 per year with an annual expense account in the amount of $20,000. But Cannon proffered a two-year contract with a starting date of January 1, 1967. The later date was significant because it meant Miller would not be representing the players during negotiations over the pension contract, which was about to expire.

The contract also included a three-day-notice termination clause if Miller was accused of public ridicule or moral turpitude. The vagueness of this clause was troubling enough, but the fact that there were no directions in the contract on how his expense account was to be managed opened him up to a virtually infinite number of moral turpitude charges. Miller insisted that the contract spell out reimbursement requirements, include the same good-conduct clause that appeared in player contracts, and begin on the original agreed-upon date. He compromised on length, signing a two and a half year pact.

At the same time they were trying to outflank Miller with the contract, the owners applied pressure to the association’s weak finances. When Miller was hired, the association’s assets totaled $5,700 and some used furniture in a rented New York office.20 The primary source of association income came from the owners. Players paid $50 in annual dues, which was not nearly enough to cover the costs of running the association. The owners enhanced the amount with funds from their own coffers (sort of: the funds actually were diverted from the amount owners had agreed to contribute to the pension fund). This was a blatant violation of the Taft-Hartley Act, but neither the owners, their legal advisors, nor Judge Cannon seemed to be concerned.

When Miller was elected instead of Cannon, as management had expected, they suddenly became aware of the Taft-Hartley Act and announced they were legally prohibited from providing any funds, thus starving the association of cash. They had no problem violating federal law when they thought Cannon would get the job, but suddenly got religion when Miller was the new hire. Miller, who was familiar with the Taft-Hartley Act, readily supported MLB’s decision. However, it meant he had a serious cash flow problem. MLB’s refusal to fund the union was less about the law than it was about putting a financial stranglehold on the union. However, it turned out to be a legal blunder. By admitting they were prohibited from funding the position by federal law, they had de facto conceded that MLB was a business, that it was engaged in interstate commerce, and that the MLBPA was indeed a union as defined under federal law, all of which would come back to haunt the owners in the future.21

To fund the association in his first year Miller negotiated a group license agreement with Coca-Cola to put player images on the underside of their bottle caps. The owners sought to scuttle the plan by refusing to license team logos. In reply, Coke simply airbrushed the team logos off of the baseball caps and proceeded with the plan. The result was a $60,000 infusion of cash, more than enough to tide over the office. During his career Miller would negotiate several such licensing agreements for the players, which produced substantial amounts of ancillary income.

PENSION NEGOTIATIONS

The final salvo fired by the owners was to employ delay tactics on the negotiations over the soon-to-expire pension agreement. They scheduled a June 6 meeting to discuss the pension. Holding such a meeting during the season was extraordinary, apparently signaling its importance. However, when Miller and the players showed up, no effort was made to negotiate. The owners initially refused to allow Miller to participate, since he was not yet under contract. Commissioner Eckert changed his mind, however, when Miller informed him that if he was not invited, none of the players would attend.

Having failed to exclude Miller, management sought to outflank the union altogether by announcing the new pension plan they had unilaterally decided upon, and then prepared a press conference to unveil it. Miller was initially stunned by the owner’s chutzpah, but recovered in time to pull Commissioner Eckert aside and point out to him that they were about to violate federal labor laws.

The owners called off the press conference and set up a series of meetings to discuss the pension plan. The old plan had allocated 40 percent of the national TV money for the All Star Game and World Series to the pension. As the value of TV rights rapidly escalated, MLB did not want to share that wealth. Instead, they proposed to contribute $4 million per year. Miller wanted to review the television contract, but the owners refused.

Miller proposed that the players’ contribution to their own pension be eliminated, commensurate with the way private pension plans were evolving.22 The $344 that players had previously contributed to the pension would instead be converted to dues. The $50 in dues they had been paying would revert to the players. Thus, players would see a $50 increase in their take home pay without losing either their pension or union membership. The owners had to approve the dues check off and agree to transfer those funds to the union, which they eventually did. All but two players signed up for the dues contribution. The degree of support stunned the owners and was a delightful surprise to Miller.

Negotiations got nowhere until Miller learned that MLB had previously broken the law by withdrawing $167,440 from the pension fund to redistribute among the owners.23 Using this as a bargaining chip, he finally closed the pension deal. The owners approved the elimination of the player contribution and the players accepted the fixed pension contribution. Miller was criticized for this concession, but he concluded that a straight cash contribution was better for the players, since it was impossible to enforce the 40 percent clause without access to the contract.

The owners had hoped that by stalling they would force Miller—who at the time still had no clear plan for funding his office—to abandon the cause. Instead, it enraged the players, and they consolidated their support behind Miller. In retrospect, the owners probably could not have done anything to better galvanize union support.

By the end of 1966, Miller’s biggest victory was the pension plan, but the most important one was solidifying the union. He added leadership and expert counsel with Richard Moss, his former colleague from the USWA, and put the union on firm financial footing with the dues check off (which cost the players nothing) and the Coca-Cola money. More importantly, the union no longer depended on the owners for funding, and their leader, Marvin Miller, was anything but their shill. Quite to the contrary, Miller was more pro-player than many of the players were. And while some took a while to trust him and buy into the idea that baseball players needed a union, they all backed him in time.

MILLER’S LEGACY

In his first six months on the job Miller delivered a new pension plan for the players. In his second year he went one better, negotiating the first basic agreement in professional sports, signed in February 1968. But the best was yet to come. Before he retired in 1982, the players had gained the right to arbitration for disciplinary issues and salaries, overturned the reserve rule, increased the size of their pensions, and saw salaries rise by nearly 2,000 percent—all without the Armageddon predicted by the owners.

“This will be the end of baseball as we knew it,” lamented Braves GM Paul Richards in reference to the dangers of negotiating (my emphasis) a collective bargaining agreement with the players. Richards was right, it was the end of baseball as the owners knew it. He just had no idea how much better things would get. Player salaries skyrocketed, attendance boomed, television revenues soared, franchise values exploded, and state-of-the-art, publicly funded stadiums sprouted like mushrooms. The owners are very protective of their financial records, but there is no evidence to support the claim that the rise in power of the MLBPA harmed the owners. They have been forced to share a bigger piece of the revenue pie, but the pie has grown exponentially since Marvin Miller arrived on the scene, allowing both sides to grow rich far beyond anything they could have imagined a half century ago.

MICHAEL HAUPERT is Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. He is fortunate enough to be able to combine his work with his hobby, teaching and researching the economics of sports and history.

An earlier version of this article first appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of “Outside the Lines,” the newsletter of the Business of Baseball committee.

Sources

Abrams, Roger, legal bases: Baseball and the Law, Philadelphia, Temple University, 1998

Burk, Robert F., Marvin Miller, Baseball Revolutionary, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2015

Haupert, Michael, Haupert Baseball Salary Database, private collection, 2016

Haupert, Michael, “Marvin Miller Takes the Helm,” Outside the Lines 22, no. 1 (Spring 2016), pp 26-32

Korr, Charles P., The End of Baseball As We Knew It: The Players Union, 1960-81, Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2002

Leahy, Michael, The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers, New York: Harper Collins, 2016

Lewis, J. Norman, “Picketing in New York State,” Labor Law Journal 5, no. 4 (April 1954), pp 263-69

Lowenfish, Lee, The Imperfect Diamond: a history of baseball’s labor wars, New York: Da Capo Press, 1980

Miller, Marvin, A Whole New Ballgame: The Sport and Business of Baseball, New York: Birch Lane Press, 1991

Swanson, Krister, Baseball’s Power Shift, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016

Notes

1 Abrams, 73.

2 Burk, 3.

3 Miller, 31.

4 Burk, 3.

5 Burk, 69.

6 Miller, 31.

7 Korr, 17.

8 Lewis (1954).

9 Lowenfish, 186.

10 Lowenfish, 191.

11 Korr, 28.

12 Korr, 33.

13 Burk, 100.

14 Lowenfish, 185.

15 Leahy, 352.

16 Burk, 101.

17 Korr, 32.

18 In 1966 only four players earned six figure incomes: Sandy Koufax $130,000, Willie Mays $125,000, Don Drysdale $105,000 and Mickey Mantle $100,000. Nine more earned between $50,000 and $100,000. Haupert Baseball Salary Database.

19 Burk, 106.

20 Burk, 100.

21 Swanson, 114.

22 For example, the steel industry had eliminated worker contributions in 1949.

23 Burk, 115.