More Relief Pitchers Belong in the Hall of Fame: Which Ones?

This article was written by John Pakutka - Elaina Pakutka

This article was published in Fall 2023 Baseball Research Journal

I still think relief pitchers are slighted or faintly patronized in most fans’ and writers’ consideration. Ask somebody to pick an all-time or all-decade lineup for his favorite team or for one of the leagues and the chances are the list will not include a late inning fireman. — Roger Angell1

Much has changed since 1985, when one of the greatest of baseball writers penned these words. Still, much has stayed the same. A simple Google search reveals the ongoing, prevailing sentiment among baseball writers and analysts that “relief pitchers are failed starters.”2 The implication seems to be that short-inning firemen really aren’t that important to team success. True greatness lies elsewhere in baseball.

No reliever has won the Cy Young Award since 2003. Many of the best never make a National Baseball Hall of Fame ballot or are summarily dismissed with less than 5% of the vote on their initial appearance. 2012 National Sportswriter of the Year Joe Posnanski does not commit the sin of exclusion Angell regularly encountered. Posnanski includes relief pitcher Mariano Rivera—and only Mariano Rivera—in The Baseball 100, his rich collection of essays on the one hundred greatest baseball players of all-time. (Even the great Rivera, it must be admitted, failed as a starter.)

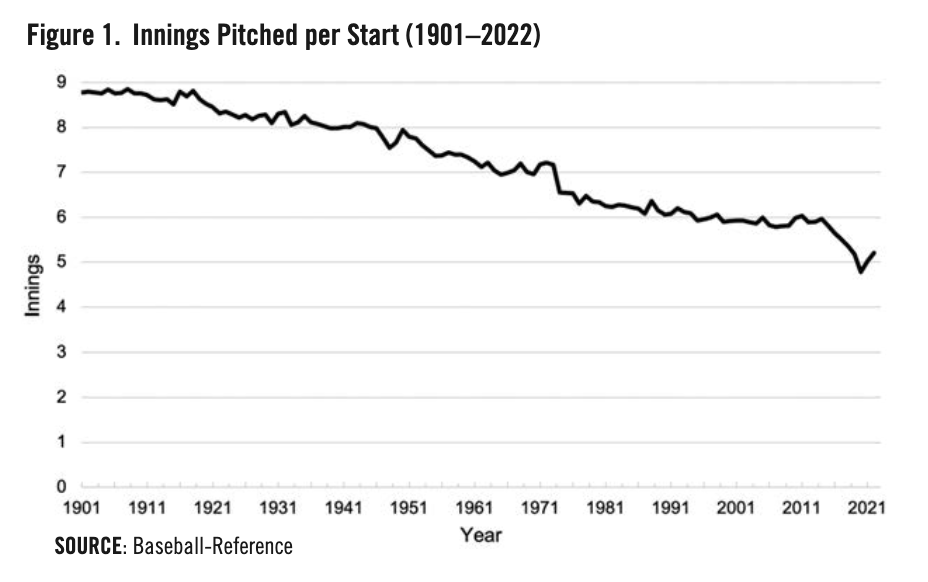

As demonstrated in Figure 1, the role of the relief pitcher has progressively increased in importance since World War I, when complete games were the norm.3 Since then, as each quarter century has passed, starters have pitched on average about an inning less per game. In 2019, Cubs President of Baseball Operations Theo Epstein put it bluntly: “More is being asked out of bullpens.”4

Many fans and analysts do not like this development, especially in its more recent iterations: bullpen games and seventh-inning specialists. In 2019, statistician Nate Silver went so far as to claim, “relief pitchers have broken baseball.” His restoration plan called for capping the number of pitchers on an MLB roster at 10.5 Despite the criticism of the game’s evolution, greatness is visible in whatever form the action takes at a given time. In the last five decades, greatness has often taken the form of Roger Angell’s “fireman.”

In 2017, sabermetric pioneer Bill James tested whether championship teams were more likely to have top-10 closers than top-10 players at other positions. James considered the period 1976 to 2016, when relief pitching assumed its modern form. (Let’s agree for now that bullpen games are the post-modern form.) James was shocked to find top-10 closers on 31 World Series champions, significantly more than any other position. According to James’s rankings, the average World Series champion had the eighth-best closer in baseball in a given year. No other position averaged better than tenth place. “The proposition that to win a World Championship you need a great closer and that a great closer is more important than a great player at other positions,” James concluded, “appears to be true.”7

Relief pitching presents great challenges: irregular, sometimes daily usage, multiple warmups before getting the call (or not), and entrance to the game in high leverage situations. Relievers must bounce back quickly from failure. The psychological command required is probably unparalleled in baseball.8

Plaques of only seven relief pitchers grace the walls of the Hall of Fame: Richard Gossage, Hoyt Wilhelm, Rollie Fingers, Bruce Sutter, Lee Smith, Trevor Hoffman, and Rivera. Converted starters Dennis Eckersley and John Smoltz also won induction. Billy Wagner will likely need the full 10 years of eligibility to complete the slow climb to 75%, the voting threshold for admission. One worries about the prospects for Craig Kimbrel, Kenley Jansen, and Aroldis Chapman, the most accomplished relievers of the past decade. Josh Hader and Liam Hendricks have barely started the journey to Cooperstown that so few relievers have completed.

Injuries have derailed many pitching careers that began on Hall of Fame trajectories. The Hall’s 10-year service requirement surely disadvantages pitchers. It is well understood that pitchers are more likely than other position players to get injured. The average pitching career is two to three years shorter than the average non-pitching career.9

In this article, we argue the best relief pitchers belong in the Hall of Fame and estimate the number of those missing in action. We review the back-of-the-baseball-card relief pitching data and then consider modern advanced analytics to produce our estimate of the best relief pitchers not in the Hall of Fame. In the concluding section, we profile briefly those we consider Hall-worthy.

THE MISSING IN ACTION

Jane Forbes Clark, Chairman of the Board of Directors of The National Baseball Hall of Fame, reminds us each year that the Hall contains the top 1% of major-league players.10 But that 1% is not evenly distributed across eras or positions. The approximately 20,000 players who have appeared in a major-league game have been almost equally split between pitchers and non-pitchers.11 Since 2000, pitchers have actually outnumbered hitters by close to a 3:2 ratio.12 Nonetheless, voters have enshrined 186 non-pitchers and just 84 pitchers.13 So 1.9% of hitters, but only 0.8% of pitchers have been inducted.

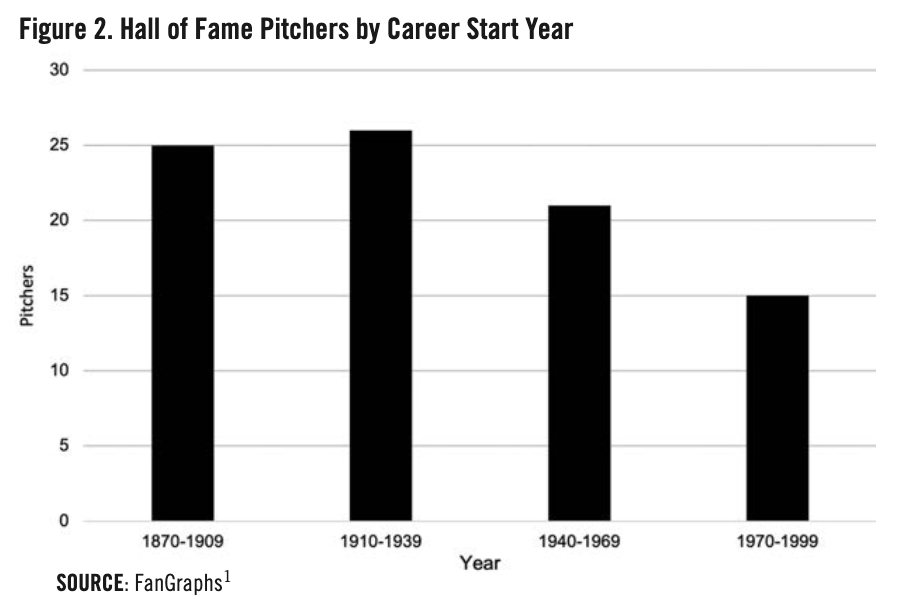

The bias against modern pitchers is much worse than the overall numbers suggest. Figure 2 breaks down the number of pitchers inducted in 30-year increments. The downward trend is actually understated by the graph, as the overall number of players has increased over time due to expansion. With the statistically deserving Roger Clemens and Curt Schilling falling off the ballot this past year, the book on 1970-1999 is mostly complete. Two pitchers of that era remain on the ballot: Andy Pettitte and Billy Wagner. Only one, Wagner, received over 20% of the vote last year.14

Why the structural discrimination? After all, as Casey Stengel famously declared, “Good pitching will always stop good hitting and vice-versa.”15 While causality is not established, this drop-off is correlated with the rise of the relief pitcher. What if instead of lamenting the rise of the reliever, we embraced it? Our best guess is that the Hall of Fame is short 10 to 15 pitchers from the 1970-99 period, and many of them are relievers.

BACK OF THE BASEBALL CARD DATA

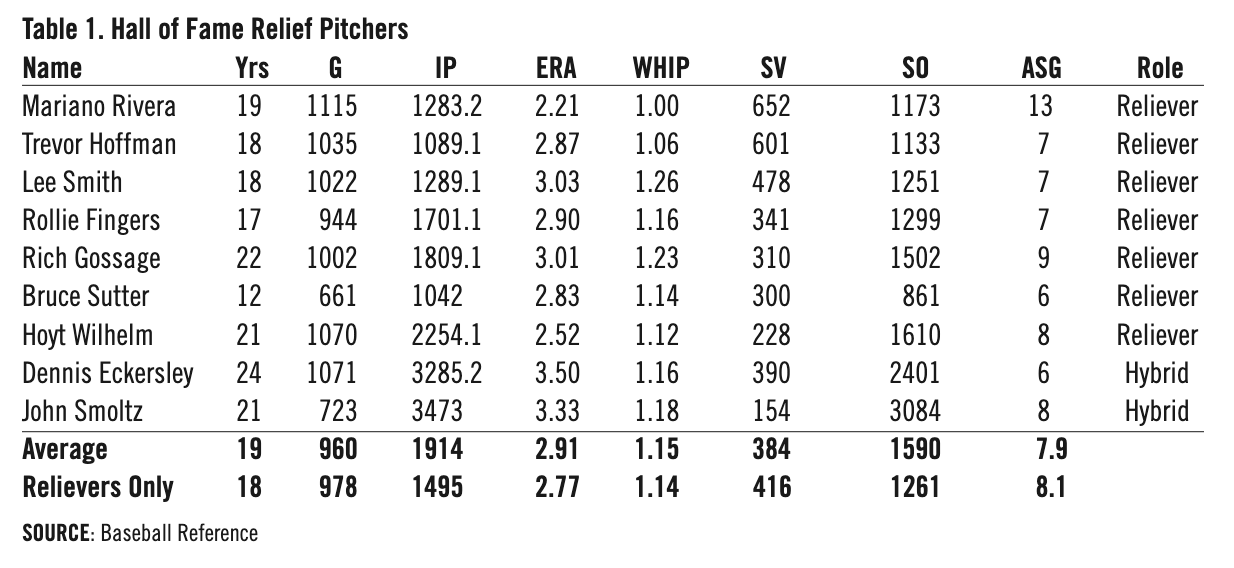

What do we know about the relief pitchers in Cooperstown? All of them saved more than 150 games and made at least six All-Star games. All but one played at least 17 years and struck out over 1,000 batters. The seven career relievers had ERAs below 3.03, WHIPs below 1.26, and at least 225 saves. (See Table 1.)

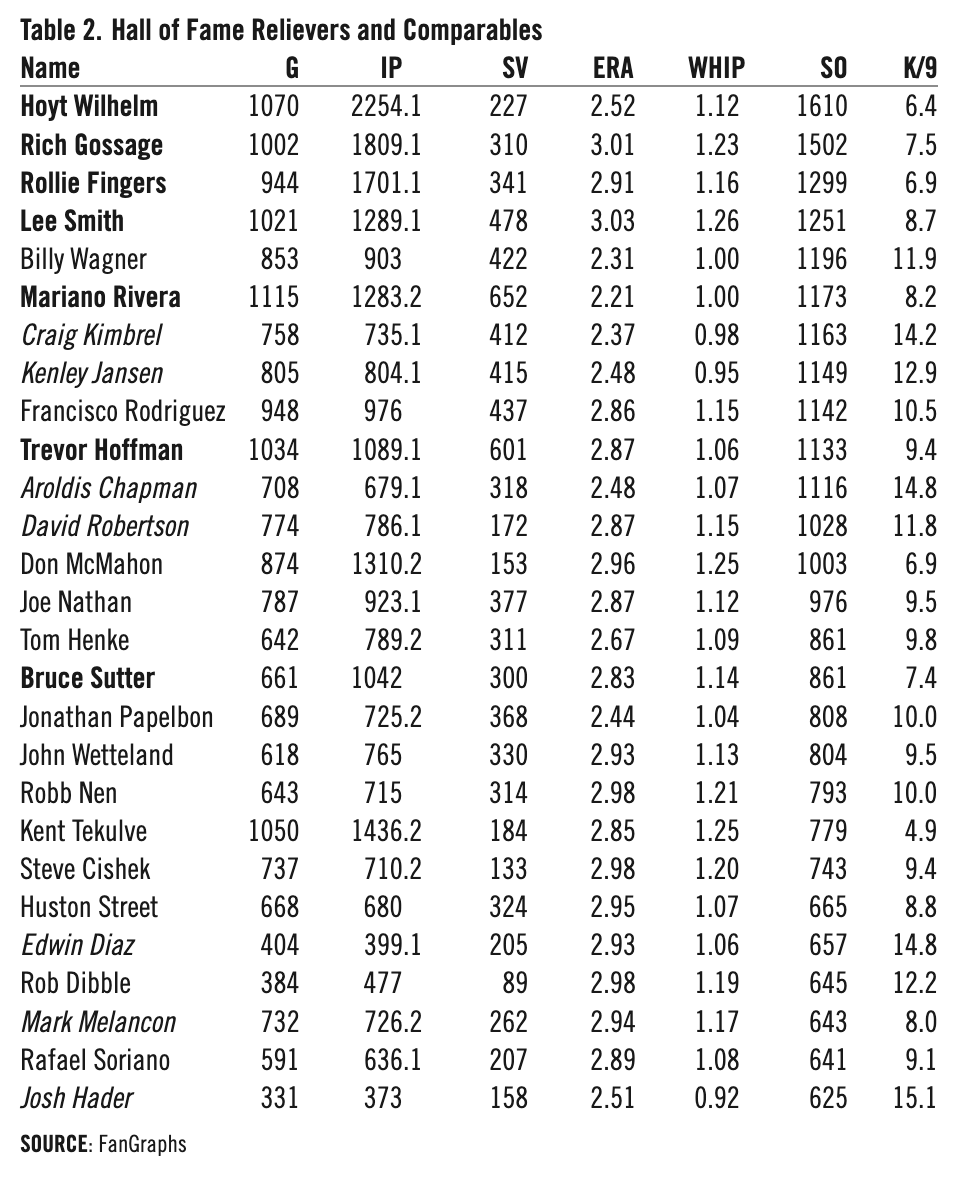

Based on that information, we found 20 pitchers from the 1970s onward who met the following criteria: better ERA and WHIP than the worst of our seven Hall of Famers, at least 600 strikeouts, and at least 85 saves.16 In Table 2, statistics for those 20 pitchers are juxtaposed with those of the Hall of Fame relievers. In this, and all following tables, Hall of Famers are in bold, and active players are italicized.

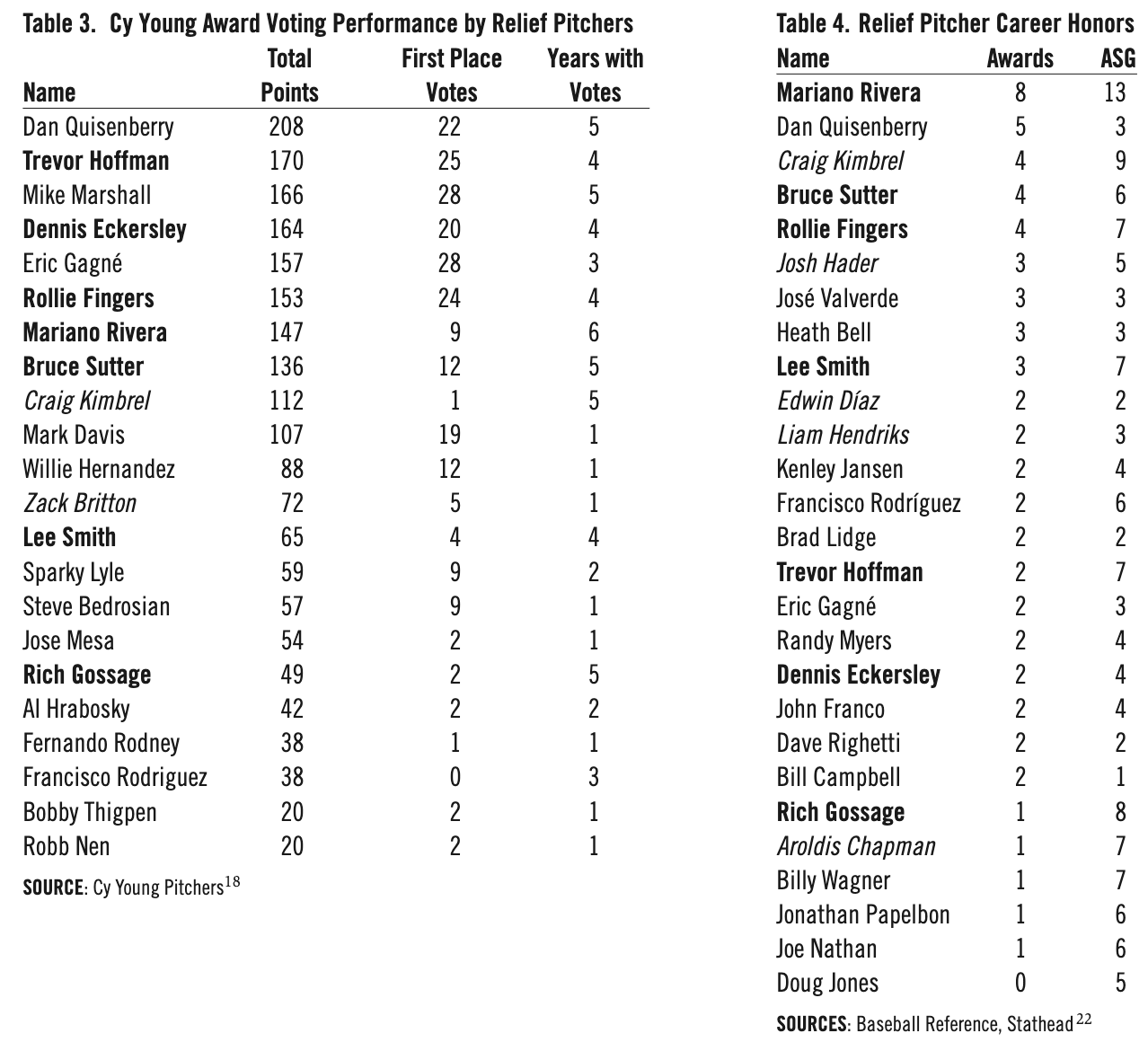

How about accolades? Sometimes the numbers do not capture the essence of the player, especially in big spots. Looking at a range of awards tells us how those around the game viewed the players contemporaneously. We looked at the Cy Young Award voting to see how often a reliever appeared on ballots, how many first-place votes they received in their career, and the total weighted points they compiled.17 Table 3 shows that by these measures, firemen Mike Marshall and Dan Quisenberry stand out for their sustained performance, with comparable numbers to the seven Hall of Famers.

Two other sets of honors warrant some consideration. The first is All-Star Game selections. Four retired relievers, Billy Wagner, Joe Nathan, Jonathan Papelbon, and Francisco Rodriguez, met the Hall of Fame standard of six selections.19

The second is a series of awards instituted specifically for relievers. From 1976 to 2012, the Rolaids Relief Man Award used a rudimentary formula with points for saves, wins, losses, and eventually blown saves to crown the best reliever in each league.20 Starting in 2014, the Reliever of the Year Award has filled the same role, though it is voted on by a panel of retired relief pitchers. From 2005 to 2013, the Delivery Man of the Year Award went to the best closer in all of Major League Baseball.21 Eight Hall of Fame relievers won these awards, six of them multiple times. Nine relievers outside of the Hall won multiple times, but Dan Quisenberry again stands out from the pack with five awards. Table 4 lists all players since 1970 who either won at least two relief awards or who had at least five All-Star selections pitching primarily as a reliever.

We examined a final set of accolades: Most Valuable Player Awards from the All-Star Game, League Championship Series, and World Series.23 It was rare for a reliever not named Mariano Rivera to win such awards. He won one of each, for a total of three. Hall of Famer Rollie Fingers won the 1974 World Series MVP, and Dennis Eckersley won the ALCS MVP in 1988. Six relievers outside the Hall won these awards: Larry Sherry was the 1959 World Series MVP; Randy Myers and Rob Dibble were co-MVPs of the 1990 NLCS; John Wetteland won the 1996 World Series MVP; Koji Uehara won the 2013 ALCS MVP; and Andrew Miller won the 2016 ALCS MVP.

ADVANCED ANALYTICS

What can modern statistics tell us about the best relievers? These metrics were mostly unavailable to twentieth-century sportswriters, but they now enable fairer comparisons within and across different eras of baseball. Many of the metrics control for the role of luck in traditional stats. We will examine four salient advanced metrics: FIP, ERA−,WAR and JAWS.

Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP) is an attempt to take the randomness of team fielding out of the equation when comparing pitchers. FIP considers only at-bats that result in a strikeout, walk, or home run, ignoring all other batted balls. “Think of it as what the pitcher’s ERA should be,” one ESPN analyst explained, “if the defense behind him turned batted balls into outs at a major-league average rate.”24 FIP rewards those pitchers with bad luck or bad fielding behind them with lower adjusted earned run averages.

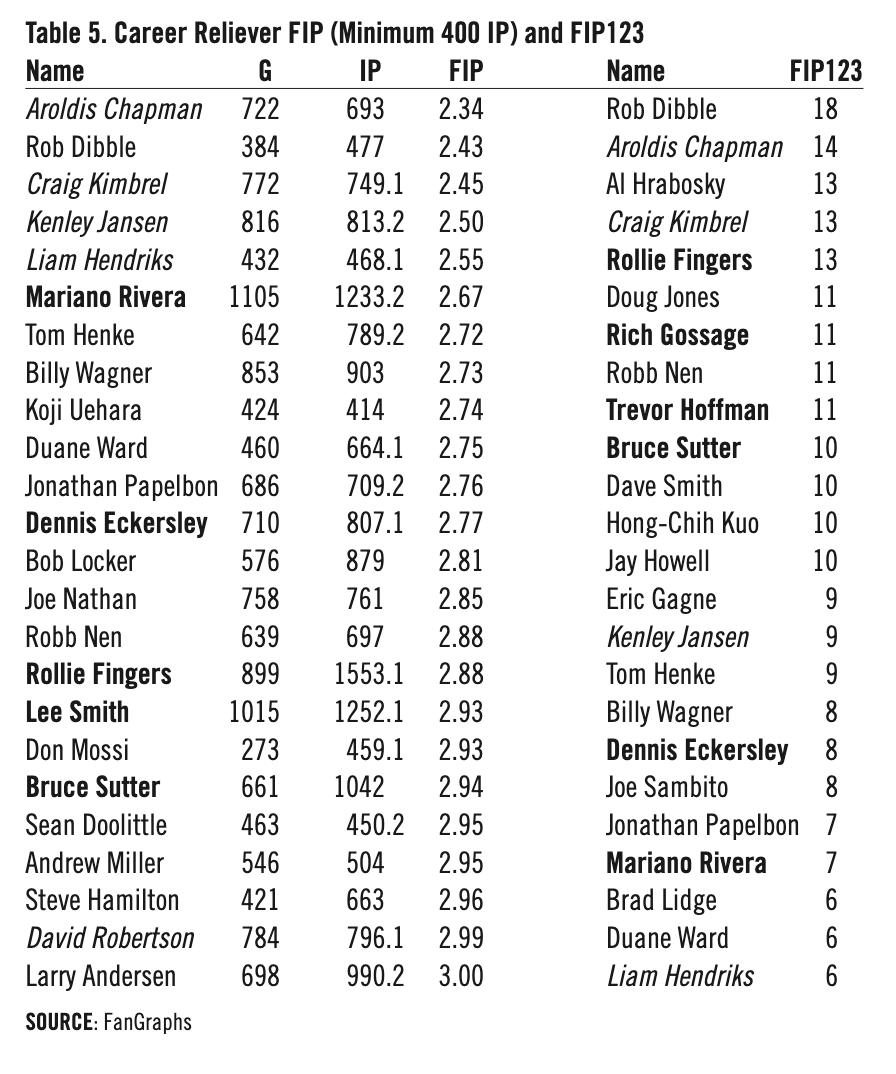

Only 22 relief pitchers have thrown at least 450 innings and maintained a FIP under three. Four of the nine Hall of Fame relievers (along with hybrid Dennis Eckersley) meet this standard, with Mariano Rivera the best among them. Four active and one retired relievers boast a better career FIP than Rivera.

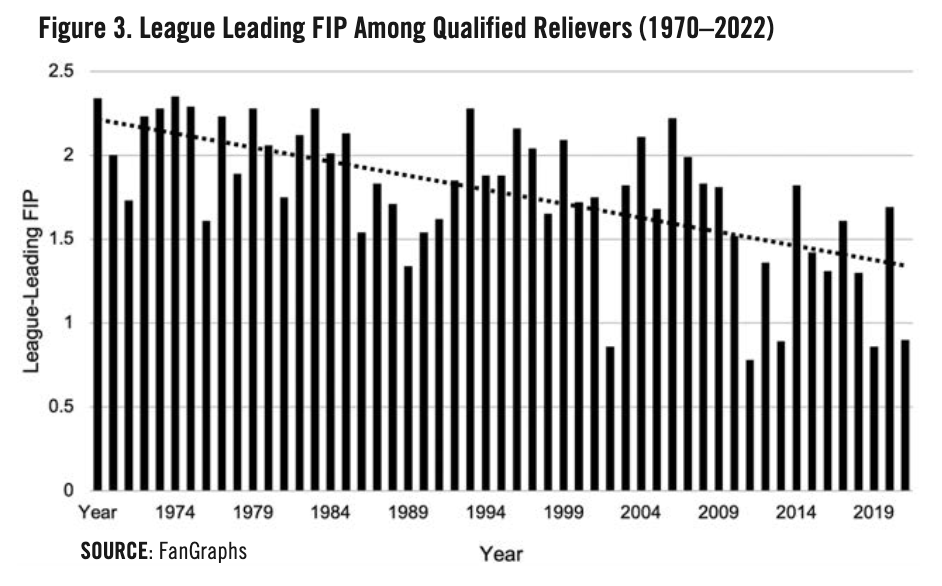

We also examined season-by-season FIP from the last five decades. What was most interesting was the short duration of relief success. Few relievers have been able to maintain league FIP dominance for more than a four-year stretch. As Figure 3 indicates, league-leading FIP has been falling over time as strikeout percentages have increased.

In an attempt to quantify career FIP dominance, we used a rudimentary scale that awarded five points for league-leading FIP among qualified relievers, three points for second place, and one point for third. We then summed each reliever’s career points and calculated what we call “FIP123.” Six Hall of Famers had dominant stretches, as did a handful of relievers outside of Cooperstown.

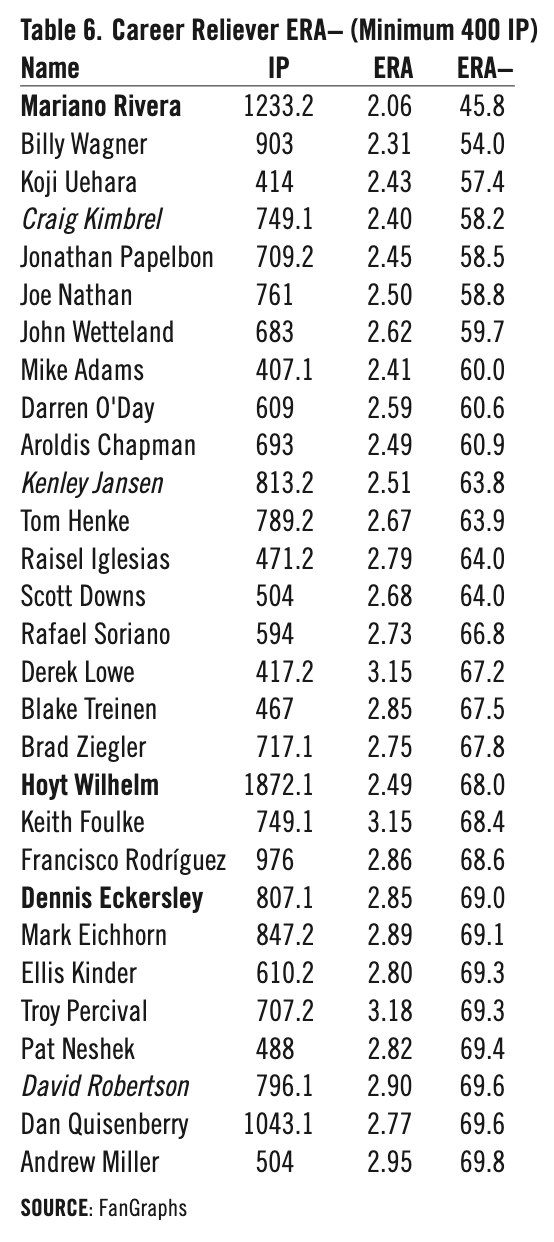

ERA– (ERA Minus) enables comparisons between pitchers of different eras, since a 3.00 ERA was more impressive in the PED Era than the Deadball Era, to name one example.25 Each pitcher’s ERA is scaled for the scoring environment: 100 is average, 80 is 20% better than average, and 120 is 20% worse.

The data here are perplexing. Mariano Rivera is safely at the top of the list, but other Hall of Famers, though still excellent, do not fare as well. Many of the best ERA– performers failed to impress the voters. Presumably those voters either did not consider ERA– or did not give it much weight. This seems like a significant oversight.

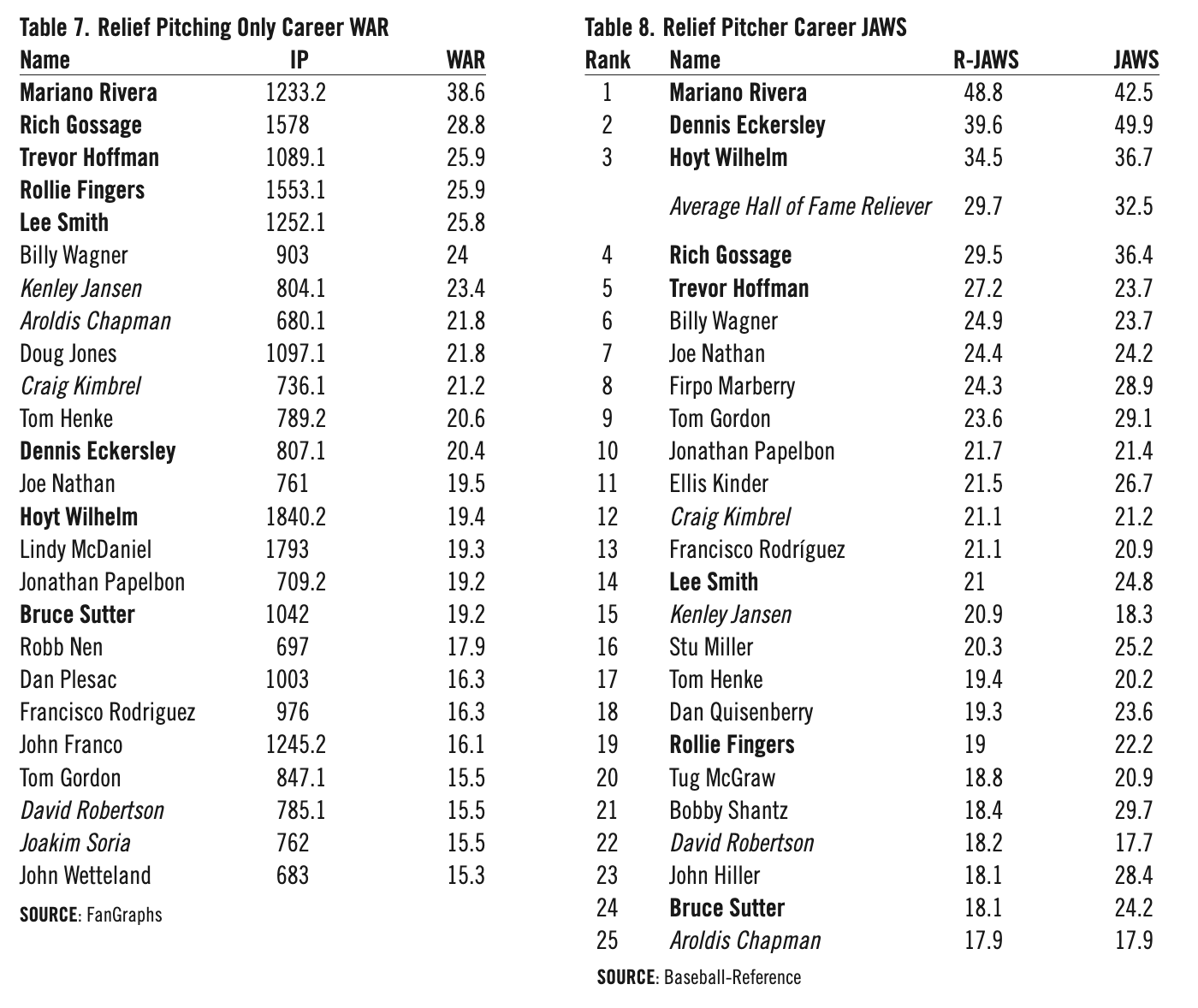

Of all the advanced metrics, Wins Above Replacement (WAR) has probably penetrated furthest into baseball’s vernacular. We use FanGraphs data in our analysis. Table 7 (page 119) provides the raw career numbers for relief pitchers. Unsurprisingly, the Hall of Famers mostly lead the race.

We excluded hybrids Eckersley and Smoltz, with career WARs of 61.8 and 79.5, from Table 7, so as not to distort the pure reliever data, but that discrepancy highlights a shortcoming in WAR. As a counting stat, it is positively correlated with number of innings pitched. The best relievers will never compile WAR in line with an average starter, and modern one-inning closers will not approach the WAR of the earlier generation of multi-inning relievers.

WAR is a good way of comparing relief pitchers, but a poor way of comparing relievers to starting pitchers or non-pitchers. Relief pitchers generate about 10% of the total WAR each year, but constitute only 3% of Hall of Famers.26

The final advanced analytic metric is probably the most important one: JAWS, the Jaffe WAR Score. Influential sabermetrician Jay Jaffe created the metric in 2004 with the explicit purpose of “measuring a candidate’s Hall of Fame worthiness by comparing him to the players at his position who are already enshrined.”27 Reliever JAWS scores, derived from Baseball Reference WAR, will be lower than those of starters, but Jaffe’s insight was in creating a measure that encourages comparisons within rather than across positions. Of course, not all will use JAWS this way, leaving relievers at a disadvantage.

The central issue with JAWS for relievers is that prevailing attitudes over time have kept the bar of entry very high. To use it as a standard is to accept the overly restrictive barriers that have kept out many of the best relievers. Table 8 shows JAWS as well as R-JAWS, a refined measure that attempts to account for the problem of comparing relievers to hybrid relievers.

Using the current 29.7 R-JAWS average as the standard keeps out not only some of the top historical candidates, but also could block the last decade’s best: Kimbrel, Jansen and Chapman. We would argue that a better application of R-JAWS would be to use the lower end Hall of Famer performance—the 18-21 range of Sutter, Fingers, and Smith—as the bar to clear. This would still weigh against the vast majority of relief pitching candidates to the HOF, but would lead to enshrinement of some deserving candidates.

THE TERRIFIC TEN

There is no straightforward formula for synthesizing the comprehensive data. Any relief pitcher who made the lists above had a stellar major league career. How might we judge who belongs in the Hall? Recall the Hall of Fame’s selection criteria: “Voting shall be based upon the player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.”28 Before our attempt to apply the criteria and find the top ten relief pitchers not (yet) in Cooperstown, we’d like to mention two groups:

Not Yet Retired but Already Worthy of Consideration: Aroldis Chapman, Kenley Jansen, Craig Kimbrel, and David Robertson.

Historical Honorable Mention: Steve Bedrosian, Francisco Cordero, Mark Davis, Eric Gagné, Tom Gordon, Willie Hernandez, John Hiller, Al Hrabosky, Sparky Lyle, Firpo Marberry, Tug McGraw, Don McMahon, Stu Miller, Randy Myers, Robb Nen, Troy Percival, Dan Plesac, Dick Radatz, Jeff Reardon, B.J. Ryan, Bobby Shantz, Rafael Soriano, Huston Street, Kent Tekulve, Duane Ward, and John Wetteland.

We’ll now count down the most deserving relievers:

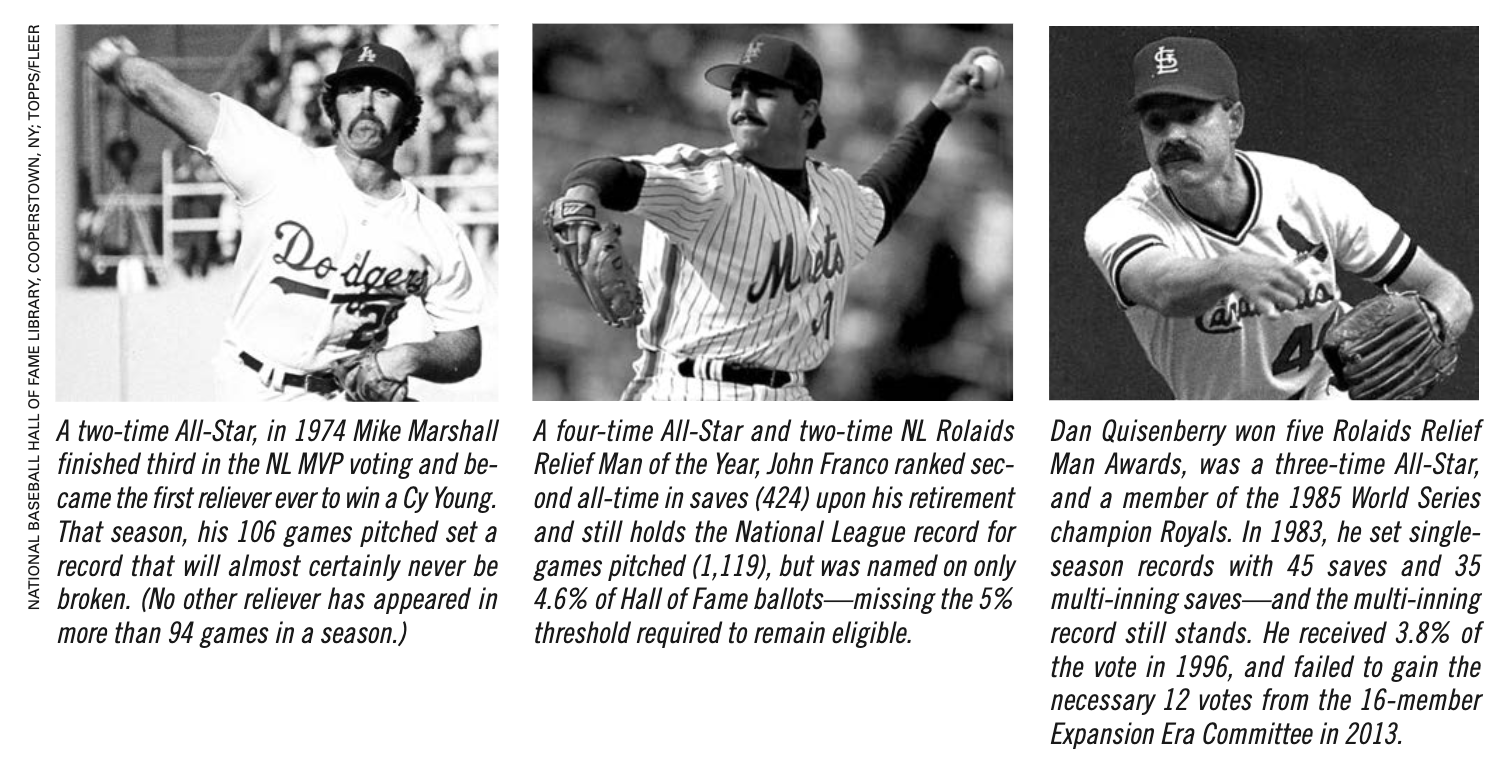

10. John Franco (“Johnny B Good”) Franco was a four-time All-Star and two-time NL Rolaids Relief Man of the Year. His 424 saves ranked second all-time upon his retirement, and are still the record for a left-handed pitcher. Only 5’10” and 170 pounds, Franco’s 1,119 games pitched are third in major-league history and first in the NL. He had a career ERA of 2.89, and 1.88 ERA in 15 postseason appearances. His 16.1 fWAR as a reliever rank twenty-first all-time.29 Franco won the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award in 2001 for his work in support of the first responders at the World Trade Center site. “He helped us get through a very difficult time,” said NYC Fire Commissioner Sal Cassano.30 In 2011, Franco was named on 4.6% of Hall of Fame ballots, just below the 5% threshold required to remain eligible.

9. Doug Jones (“The Sultan of Slow”) Jones was a five-time All-Star whose 303 saves ranked second all-time when he retired. Although his fastball topped out in the mid-80s, his 21.8 fWAR as a reliever rank ninth all-time. Released by the Brewers at age 27, he paid his own way to spring training with Cleveland, where he developed a devastating changeup that saved his career.31 Jones died of COVID-19 complications at the age of 64 in 2021.32 He received only 0.4% of the vote in 2006.

8. Rob Dibble (“The Nasty Boy”) Dibble was a two-time All-Star who won the 1990 NLCS MVP en route to a World Series championship with the Reds. Injuries and the 1994 strike limited his playing career to seven years, but his dominance over that period was Hall-worthy. Dibble had a career ERA of 2.98 and WHIP of 1.19. Among retired relievers with at least 450 innings pitched, he is the all-time leader in FIP at 2.43. Dibble’s 12.17 strikeouts per nine innings, more than any reliever in Cooperstown, came at a time well before strikeout rates across the league exploded. At 213, his K%+ is second-highest among all pitchers with at least 200 innings pitched. As a setup man in 1989, Dibble didn’t receive a single vote for the NL Cy Young despite a better WHIP, FIP, fWAR, and strikeout rate than winner Mark Davis, who led the league with 44 saves. Dibble’s 1990 numbers were even better and included 29 saves, but he still earned no Cy Young votes. Dibble established the prototype for the shutdown set-up man role. His short but stellar career is an argument against the Hall’s 10-year career length requirement. Dibble continues his work in baseball as a Connecticut ESPN radio host and youth coach.

7. Jonathan Papelbon (“The Strangler”)33 Papelbon was a six-time All-Star and played on the 2007 World Series champion Red Sox. He ranks tenth all-time with 21.7 R-JAWS, and eleventh with 368 saves. Papelbon set a postseason record with 26 consecutive scoreless innings to start his career.34 He danced the Irish Jig at Fenway after the Red Sox clinched the AL East title in 2007, earning forever the enmity of Yankees fans.35 A hotheaded competitor, Papelbon earned multiple suspensions, including one for a dugout fight with Bryce Harper and another for throwing at the head of Manny Machado.36 He received only 1.3% of the vote in 2022.

6. Tom Henke (“The Terminator”) Henke was a two-time All-Star, winner of the 1995 NL Rolaids Relief Man Award, and was on the 1992 World Series champion Blue Jays. When he retired, his 311 saves ranked fifth all-time. His 861 career strikeouts match Bruce Sutter, but his 2.67 ERA and 1.09 WHIP are better. He ranks seventeenth all-time with 19.4 R-JAWS. Since retirement, he has hosted an annual golf tournament to raise money for The Special Learning Center, a school for handicapped children.37 Henke received only 1.2% of the vote in 2001. Asked whether Henke deserved induction, Tony La Russa declared, “Absolutely. Tom had everything you want in a Hall of Famer.”38

5. Joe Nathan (“Stand Up and Shout”) A six-time All-Star, Nathan won the AL Rolaids Relief Man Award in 2009. His 377 saves ranked eighth when he retired. Among pitchers with at least 100 saves, his 89.1% save percentage is the third-highest of all-time. Among relievers, his 19.5 fWAR rank thirteenth all-time, and his 24.4 R-JAWS rank seventh. By his own admission “not a good high school athlete,” Nathan didn’t throw a single pitch in high school or college at Division III Stony Brook, where he played shortstop and was a two-time Academic All-American.39 He finished with only 4.3% of the vote. “This is above and beyond what I dreamt about,” Nathan said in response, “My dreams were, ‘I’d love to play in the big leagues someday.’ To be on this ballot is an honor in itself. That’s baseball heaven.”40

4. Mike Marshall (“Iron Mike”) A two-time All-Star, in 1974 Marshall finished third in the NL MVP voting and became the first reliever ever to win a Cy Young. That season, his 106 games pitched set a record that will almost certainly never be broken. No other pitcher has ever appeared in more than 94 games. Marshall relied on an elusive screwball to lead his league in saves three times, and is one of five relievers to receive Cy Young votes in five or more seasons. Marshall earned a Ph.D. in Exercise Physiology from Michigan State in 1978, then led the AL in saves in 1979. At his Florida pitching academy, Marshall pioneered innovative training methods that have since become widespread, such as weighted balls, video, and focus on spin. Marshall received 1.5% of the vote in 1987. He died in 2021 at the age of 78. “He lived long enough to see some of his most foundational ideas,” ESPN’s Jeff Passan reported, “co-opted by major league organizations and spread to the masses.”41

3. Dan Quisenberry (“Quis”) Despite going undrafted, Quisenberry won five Rolaids Relief Man Awards, second only to Mariano Rivera. A three-time All-Star and member of the 1985 World Series champion Royals, Quisenberry is one of five relievers who received Cy Young votes in five or more seasons. His 19.3 R-JAWS ranks eighteenth. In 1983, Quisenberry set single-season records with 45 saves and 35 multi-inning saves. The multi-inning record still stands.42 A submariner lacking high-end velocity but possessing pinpoint control, Quisenberry relied on a devastating sinker. “The pressures on him are so tough—you have no idea, because he doesn’t let it show,” teammate Paul Splittorff said in 1984. “His job is the toughest on the roster, because this club is going to sink or swim with him.”43 Known for his wit, when accepting the 1982 Rolaids Award, Quisenberry said, “I want to thank all the pitchers who couldn’t go nine innings and manager Dick Howser who wouldn’t let them go.”44 Quisenberry died from brain cancer, as had Howser, in 1998 at the age of 45. He received 3.8% of the vote in 1996, and failed to gain the necessary 12 votes from the 16-member Expansion Era Committee in 2013.

2. Francisco Rodriguez (“K-Rod”) Rodriguez was a six-time All-Star and played for the 2002 World Series champion Angels. He won the Rolaids Relief Man Award twice, and earned Cy Young votes in three seasons. His 62 saves in 2008 are still an MLB record. Among relievers, he ranks fourth with 437 saves, tenth with 1,142 strikeouts, twentieth with 16.3 fWAR, and twelfth with 21.1 R-JAWS. As a rookie and the youngest pitcher in the American League, Rod-riguez tied a record with five postseason wins in 2002.45 Two off-the-field domestic incidents—one of which resulted in a guilty plea—will dissuade some voters.46 After receiving 10.8% of the vote in 2022, Rodriguez will appear on the ballot again in 2023.

1. Billy Wagner (“Billy the Kid”) A seven-time All-Star, Wagner was named the NL Rolaids Relief Man in 1999. Among relievers with at least 300 innings pitched, his 54 ERA− is second all-time, his 190 K%+ is fourth, and his 1.00 WHIP is tenth. The 5’10” southpaw boasts 422 saves, 1,196 strikeouts, 24 fWAR, and 24.9 R-JAWS ranking sixth among relievers in all four categories. In his sophomore season at Division III Ferrum College, Wagner set an NCAA record by averaging 19.1 strikeouts per nine innings.47 Wagner’s charity, Second Chance Learning Center, provides at-risk youths with counseling and other assistance.48 In 2022, his eighth year on the ballot, he received votes from 68.1% of the voters, up 17% from 2021.

CONCLUSION

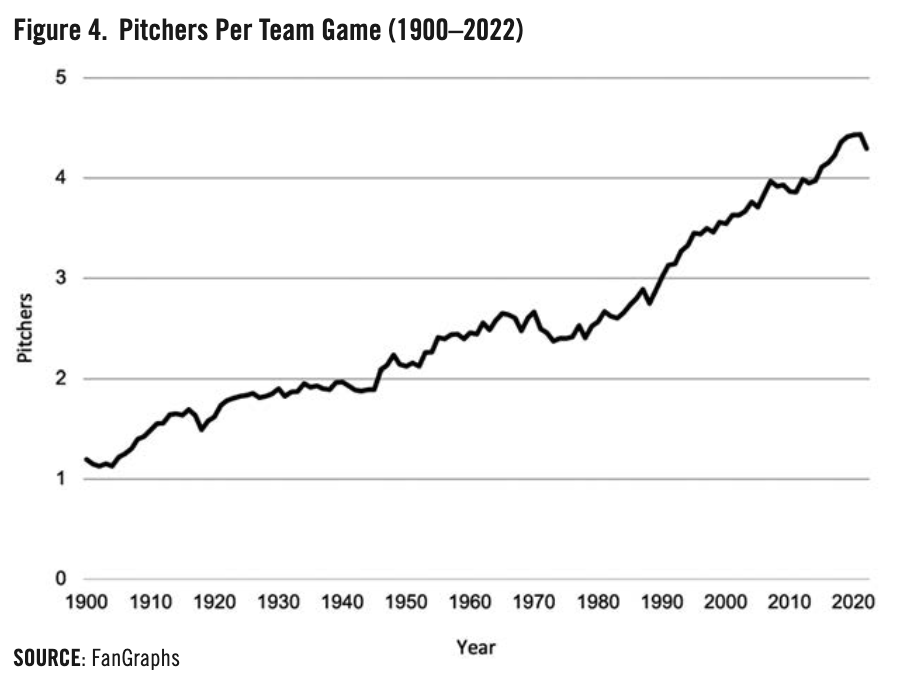

Today, the average team uses over four pitchers per game, up from 2.5 in the 1970s.49 Only one of those pitchers is a starter. (See Figure 4.) According to FanGraphs, 10,236 players have pitched in the American and National Leagues. Of those players, 54.2% pitched more innings as a reliever, and 63.2% made more appearances as a reliever. 34.3% of them pitched in relief without ever starting a game, but only 4.6%, just 495 pitchers, started without ever entering a game in relief. 4,402 pitchers are credited with at least one save, and 2,447 are listed as qualified relievers.50

Were the “best 1%” standard applied to this subset of relief pitchers, 20 to 30 of them would be in the Hall of Fame. Only nine have won induction. The standard for admission has been set extremely high for those excelling in this crucial role. In 1985, Roger Angell reminded his readers of the “clear evidence that relief men—the best of them, at least—are among the most highly rewarded and most sought after stars of contemporary baseball.”51 With the ever-expanding dominion of the relief pitcher, his argument seems even more salient today.

It is up to the Era Committees to induct more of history’s best relief pitchers into their ranks. The news for those eligible today and in the future seems promising. Billy Wagner’s election seems likely in the next year or two. Francisco Rodriguez cleared the 5% bar in his initial vote, unlike earlier superb relief pitchers. These developments suggest that future Cooperstown-worthy closers will receive warmer welcomes from the Baseball Writers Association of America.52

ELAINA PAKUTKA, a Red Sox fan, is a ninth grade student at Hopkins School in New Haven, Connecticut. She is a sportswriter for The Razor, the school’s student newspaper. Her dad, JOHN PAKUTKA, a Yankee fan, is a health management and policy consultant. He is the co-author of Getting Away with Murder: Prescription Drug Coverage in America (American Affairs, Winter 2018) and Social Insurance: America’s Neglected Heritage and Contested Future (Sage/Congressional Quarterly, 2013). See sixthreats.com for a book summary and John’s blog. John and Elaina can be reached at jpakutka@thecrescentgroup.com.

Notes

1 Roger Angell, “Quis,” The New Yorker, September 30, 1985: 41-72.

2 Matt Snyder, “Why Billy Wagner’s Hall of Fame case will show how voters judge relievers moving forward,” CBSSports.com, January 26, 2021, https://www.cbssports.com/mlb/news/why-billy-wagners-hall-of-fame-case-will-show-how-voters-judge-relievers-moving-forward/, accessed January 26, 2021. See also Rick Weiner, “10 Best ‘Failed’ Starters in MLB History,” Bleacher Report, May 25, 2013, https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1650473-10-best-failed-starters-in-mlb-history, accessed July 28, 2022.

3 Emma Baccellieri, “Why Shorter Starts for Pitchers Shouldn’t Be Surprising in 2020,” Sports Illustrated, August 18, 2020, https://www.si.com/mlb/2020/08/18/shorter-starts-pitchers-trend, accessed May 31, 2022.

4 Alden Gonzalez, “Why relief pitchers have been so hard to figure out,” ESPN.com, June 17, 2019, https://www.espn.com/mlb/story_/id/26989473/why-relief-pitchers-hard-figure-out.

5 Nate Silver, “Relievers Have Broken Baseball. We Have A Plan to Fix It,” FiveThirtyEight, February 25, 2019, https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/relievers-have-broken-baseball-we-have-a-plan-to-fix-it/, accessed May 31, 2022.

6 FanGraphs, https://www.fangraphs.com/leaders/major-league?pos=all&lg=al&lg=nl&qual=y&type=8&month=0&ind=0&team=0%2Css&startdate=&enddate=&stats=sta&season1=1900&season=2022&sortcol=0&sortdir=asc&pagenum=1, accessed August 28, 2023.

7 Bill James, “The All Important Closer,” February 3, 2017, https://www.billjamesonline.com/the_all_important_closer/.

8 An illustration of a reliever who mastered anxiety: As a teenager, Mariano Rivera helped his father aboard an aging fishboat in shark-infested waters. He saw an uncle die in a horrific shipboard accident. More than once, the young Rivera feared for his life as his father tinkered with failing pumps and engines and the boat, weighed down by the day’s catch, took on water. “I wonder if I am going to have to swim for my life,” Rivera recounted. “I wonder how many of us—or if any of us—will make it.” We suspect facing down even the best hitters did not provoke comparable anxiety. Mariano Rivera with Wayne Coffey, The Closer, My Story (New York: Little Brown and Company, 2014), 22-30.

9 Robert Arthur, “Attrition by Position: How Long Do Players at Each Position Last?” Baseball Prospectus, March 13, 2014, https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/23041/attrition-by-position-how-long-do-playersat-each-position-last/.

10 John and Elaina attended the 2022 Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, 2022 Baseball Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony transcript, July 24, 2022, https://collection.baseballhall.org/objects/21660/2022-baseball-hall-of-fame-induction-ceremony-transcript?ctx=3edd374352a89ee351d3edb0f5d903521b22b77d&idx=0, accessed July 25, 2022.

11 The Hall of Fame puts the number at over 23,000.

12 Jordan Shusterman, “MLB is Closing in on its 20,000th Player, and We’re Counting Them Down,” FOX Sports, April 28, 2021, https://www.foxsports.com/stories/mlb/20000-players-countdown-major-league-debuts.

13 “Hall of Famers by Position,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/hall-of-famer-facts/hall-of-famers-by-position, accessed June 1, 2022.

14 Baseball Hall of Fame Vote Tracker, http://www.bbhoftracker.com/, accessed June 8, 2022.

15 Casey Stengel Quotes, Baseball Almanac, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/quotes/quosteng.shtml, accessed August 16, 2022.

16 Holds and blown saves were not tracked until late in the period and could not be included in the analysis. To ensure we did not exclude dominant setup men, we used a low bar for saves.

17 MLB Cy Young Award Winners, Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/awards/cya.shtml, accessed July 12, 2022.

18 Cy Young Pitchers, https://cyyoungpitchers.com/voting-history/, accessed August 7, 2023.

19 Most Seasons on All-Star Roster, Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/leaders_most_asgame.shtml, accessed July 12, 2022.

20 MLB Mariano Rivera, Trevor Hoffman, & Rolaids Relief Award Winners, Baseball-Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/awards/reliever.shtml, accessed September 11, 2023.

21 MLB Delivery Man of the Year Award Winners, Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/awards/delivery.shtml, accessed September 11, 2023.

22 Stathead, 2023. https://stathead.com/tiny/HrHS5, accessed September 11, 2023.

23 MLB Awards, ESPN.com, https://www.espn.com/mlb/history/awards/_/id/62, accessed July 12, 2022.

24 MLB stat definition: What is FIP?, ESPN.com, February 17, 2011, https://www.espn.com/blog/statsinfo/postr_/id/62051/mlb-stat-definition-what-is-fip, accessed July 10, 2022.

25 Bryan Grosnick, “ERA+ Vs. ERA-,” Beyond the Box Score, September 14, 2012, https://www.beyondtheboxscore.com/2012/9Z14/3332194/era-plus-vs-era-minus.

26 FanGraphs, https://www.fangraphs.com/leaders.aspx?pos=all&stats=bat&lg=all&qual=y&type=8&season=2021&month=0&season1=2021&ind=0&team=0&rost=0&age=0&filter=&players=0&startdate=&enddate=, accessed July 16, 2022.

27 Jay Jaffe, The Cooperstown Casebook (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, St. Martin’s Press, 2017), 23. Three-time National Sportswriter of the Year Peter Gammons keeps Jaffe’s seminal tome The Cooperstown Casebook on his “essentials desk right through the end of December when (his) ballot is mailed.” See also Michael Silverman, “Controversial Candidates Still Get the Nod,” The Boston Globe, January 10, 2023, accessed August 5, 2023: https://apps.bostonglobe.com/sports/graphics/2023/01/baseball-hall-of-fame-voting-2023/.

28 Hall of Fame Election Requirements, BBWAA.com, https://bbwaa.com/hof-elec-req/, accessed August 5, 2023.

29 FanGraphs, https://www.fangraphs.com/leaders/major-league?pos=all&lg=all&type=8&season=2023&month=0&season1=1871&ind=0&team=0&rost=0&players=0&stats=rel&qual=0, accessed July 21, 2022.

30 Rory Costello, “John Franco,” SABR.org, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/john-franco/, accessed July 21, 2022.

31 Richard Riis, “Doug Jones,” SABR.org, February 11, 2022, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/doug-jones/, accessed July 21, 2022.

32 Dan Lyons, “Five-Time MLB All-Star Doug Jones Has Died,” SI.com, November 22, 2021, https://www.si.com/mlb/2021/11/22/doug-jones-cleveland-baseball-death-cause-covid-19-astros-phillies, accessed July 21, 2022.

33 The Boston Strangler or the DC Strangler? We like Boston, but take your pick. Grey Papke, “Jayson Werth has Funny New Nickname for Papelbon,” June 14, 2016, https://www.yardbarker.com/mlb/articles/jayson_werth_has_funny_new_nickname_for_papelbon/s1_127_21101593, accessed July 21, 2022.

34 Jay Jaffe, “JAWS and the 2022 Hall of Fame Ballot: Jonathan Papelbon,” FanGraphs, January 20, 2022, https://blogs.fangraphs.com/jaws-and-the-2022-hall-of-fame-ballot-jonathan-papelbon/, accessed July 21, 2022.

35 Gordon Edes, “Sox Clinch First Division Title in 12 Years,” The Boston Globe, September 29, 2007, http://archive.boston.com/sports/baseball/redsox/articles/2007/09/29/sox_clinch_first_division_title_in_12_years/ (Accessed July 21, 2022). See also Jack Curry, “Save the Last Dance for the Red Sox’ Closer,” The New York Times, October 28, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/28/sports/baseball/28papelbon.html, accessed July 21, 2022.

36 Gabe Lacques, “Jonathan Papelbon Suspended Seven Games for Obscene Gesture,” USA Today, https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/mlb/2014/09/15/jonathan-papelbon-suspended-seven-games-obscene-gesture/15697537/, accessed July 21, 2022.

37 Eric Vickrey, “Tom Henke,” SABR.org, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/tom-henke/, accessed September 11, 2023.

38 Graham Womack, “Tom Henke’s Early Retirement Might’ve Cost Him the Hall of Fame,” The Sporting News, June 30, 2017, https://www.sportingnews.com/mlb/news/tom-henke-blue-jays-cardinals-rangers-stats-saves-best-closers-mlb-history-hall-of-fame/1dvq9xt8g8gnb1v18pq9t7omq4, accessed July 21, 2022.

39 David Bilmes, “Joe Nathan,” SABR.org, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/joe-nathan/, accessed July 21, 2022.

40 David Bilmes, “Joe Nathan,” SABR.org, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/joe-nathan/, accessed July 21, 2022.

41 Jeff Passan, “Why Pitching as We Know it Today Wouldn’t Exist Without Mike Marshall,” ESPN.com, June 2, 2021, https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/31553574/why-pitching-know-today-exist-mike-marshall, accessed July 19, 2022.

42 Joe Posnanski, “Dan Quisenberry for the Hall of Fame,” NBC Sports, November 5, 2013, https://mlb.nbcsports.com/2013/11/05/dan-quisenberry-for-the-hall-of-fame/, accessed July 30, 2022.

43 Roger Angell, “Quis,” The New Yorker, September 30, 1985: 41-72.

44 “Dan Quisenberry Quotes,” Baseball Almanac, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/quotes/quoquis.shtml, accessed July 20, 2022.

45 Tyler Kepner, “Giants Find Fault with Perfect Reliever,” The New York Times, October 24, 2002, https://www.nytimes.com/2002/10/24/sports/baseball/giants-find-fault-with-perfect-reliever.html, accessed July 20, 2022.

46 “Francisco Rodriguez arrested in Sept.,” ESPN.com, October 13, 2012, https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/8497593/, accessed September 11, 2023.

47 Jake Mintz, “Billy Wagner Went from Div. III to MLB with ‘Magic’ Fastball,” FOX Sports, January 19, 2022, https://www.foxsports.com/stories/mlb/billy-wagner-went-from-div-Ni-to-mlb-with-magic-fastball, accessed July 19, 2022.

48 Leslie Heaphy, “Billy Wagner,” SABR.org, March 15, 2021, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/billy-wagner/, accessed July 19, 2022.

49 Kerry Miller, “The Newest Trend Taking over MLB in 2022 and Beyond,” Bleacher Report, April 27, 2022, Accessed August 7, 2023: https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2955675-the-newest-trend-taking-over-mlb-in-2022-and-beyond, accessed August 7, 2023. See also Nate Silver, “Relievers Have Broken Baseball. We Have A Plan to Fix It,” FiveThirtyEight, February 25, 2019, https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/relievers-have-broken-baseball-we-have-a-plan-to-fix-it/, accessed May 31, 2022.

50 FanGraphs, https://www.fangraphs.com/leaders/major-league?pos=all&stats=pit&lg=al%2Cnl&qual=y&type=8&season=2023&month=0&season1=1871&ind=0&team=0&rost=0&players=0, accessed September 10, 2023.

51 Roger Angell, “Quis,” The New Yorker, September 30, 1985: 41-72.

52 2023 Hall of Fame Voting, Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/awards/hof_2023.shtml, accessed August 5, 2023.