Ron Shelton: On Cobb, Bull Durham, and Baseball-On-Screen

This article was written by Rob Edelman

This article was published in From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors

In the baseball fantasy Field of Dreams, the spirits of various diamond greats come to play ball on a field rising magically out of Midwestern corn stalks. “Ty Cobb wanted to play,” chuckles Shoeless Joe Jackson. “But no one could stand the son-of-a-bitch when we were alive, so we told him to stick it.”

In the baseball fantasy Field of Dreams, the spirits of various diamond greats come to play ball on a field rising magically out of Midwestern corn stalks. “Ty Cobb wanted to play,” chuckles Shoeless Joe Jackson. “But no one could stand the son-of-a-bitch when we were alive, so we told him to stick it.”

In 1994, this “son-of-a-bitch” was the subject of a film all his own. It was Cobb, written and directed by Ron Shelton, minor-league journeyman turned major-league Hollywood player.

On the field Tyrus Raymond Cobb, the Georgia Peach, had an exemplary major-league career, lasting from 1905 through 1928. No other batter has matched his lifetime batting average of .366. Only Pete Rose has bested his total of 4,189 hits.

The story goes that, in 1958, Lefty O’Doul was questioned about how Cobb would fare against contemporary pitching. O’Doul responded that Cobb might hit .340. Why so low, he was asked? “You have to remember,” he replied, “the man is 72 years old.”1

Off the field, however, Ty Cobb was something else altogether. He was an unabashed racist who lamented the South’s loss of the Civil War. He constantly carried a loaded gun. He was a vicious, foul-mouthed brawler and tyrant. It is no surprise that he was so disliked by his fellow players.

“Cobb was the original trash talker,” Shelton explained in an interview just after his film’s release. “He was a Southern redneck who taunted everybody all the time, even his own teammates.”2 This is the Ty Cobb that Shelton depicts on screen.

But Cobb does not focus on the man in his playing days. It is set in the twilight of Cobb’s life, and examines what Shelton described as the “curious relationship” between Cobb (played by Tommy Lee Jones) and sportswriter Al Stump (Robert Wuhl). In 1960 Stump was hired to ghostwrite the faded legend’s whitewashed autobiography, My Life in Baseball: The True Record.

The two spent nearly a year together. A truer picture of the man emerged in Stump’s 1994 book Cobb: A Biography, in which Cobb is portrayed as an argumentative, sickly, booze-soaked old man who was, as Stump writes, “contemptuous of any law other than his own.”3

“He’s in very poor health now,” Shelton said of Stump, who passed away in December 1995, one year after the film’s release. “But I got to know him very well before I began writing the film. For this reason it’s filled with many anecdotes about Cobb that had never before been printed.”

Shelton is one for making literary references, in both his films and his conversation. He contrasted the Cobb-Stump relationship to what might have been “if Samuel Johnson hired Boswell at gunpoint.” In Bull Durham, his instant-classic baseball film, which came to theaters in 1988, one of his characters is noted for quoting Walt Whitman and William Blake.

But while the subject of Cobb is a Hall of Fame ballplayer, Shelton does not consider it a baseball movie. He sees no relation between Cobb and Bull Durham, which is as pure a baseball story as has ever been filmed.

“I am fascinated by people like Ty Cobb, who can be so sociopathic and dysfunctional outside their craft and so brilliant in it,” he said. “Cobb was a fascinating set of contradictions. He was an uncommonly brilliant athlete who was equally uncommonly obsessed. You can only marvel at his numbers – and also at his abominable behavior.”

He added that the film also “is about an old man who’s been called immortal, and how he faces his mortality.” In Cobb, Shelton asks questions that are well worth pondering, and which resonate today: Why do we in America make heroes out of people like Ty Cobb? Why do we forgive the abysmal behavior of a man whose main contribution to society is the ability to hit .366?

Not all less-than-saintly sports heroes – and they are endless, and have appeared on big-time rosters for decades – are as downright appalling as Cobb. Others simply are uncouth. “Deion Sanders, for instance, can get away with his outrageous behavior because he’s so damn good,” Shelton noted. “He can pull off all his jive. But if he wasn’t Deion Sanders, he’d just be another boor.”

Others, meanwhile, are more paradoxical. Shelton said his conception of Cobb was being contrasted to O.J. Simpson. It is a comparison he does not buy. “O.J. Simpson is a man with a public image and a private reality,” he observed. “Ty Cobb was completely different. His antics were not hidden. All of them made the front page. But nobody cared. Because he hit .367, he was able to meet with presidents. If he had hit .267, he would have been in jail.”4

The critical reaction to Cobb was what Shelton described as “most curious” and “schizophrenic.” He explained, “I could show you 400 reviews. Two hundred of the critics loved the film; 200 hated it. There’s been no middle ground.”

Two examples: Peter Travers, in Rolling Stone, dubbed Cobb “the Raging Bull of baseball movies,” adding that “Jones gives a landmark performance (and) Shelton’s strong, stinging film (is) one of the year’s best. …”;5 the San Francisco Chronicle’s Peter Stack described the film as a “histrionic portrait (that) comes across like a fly ball that thuds on the ground. …” Stack labeled Jones’s performance “tiresome,” noting that the actor “succeeds only in running the awful and pathetic Cobb into the ground.”6

The uneven nature of its critical reception plus the inability of Warner Bros., the film’s distributor, to properly market Cobb resulted in a limited release for the film. On the other hand, Bull Durham, Shelton’s first feature as director-writer, not only was a smash hit: It earned him the Writers Guild of America’s Best Original Script award, the Best Script prize from the National Society of Film Critics (as well as kudos from critics’ organizations in Boston, Los Angeles, and New York), and a Best Original Screenplay Academy Award nomination.

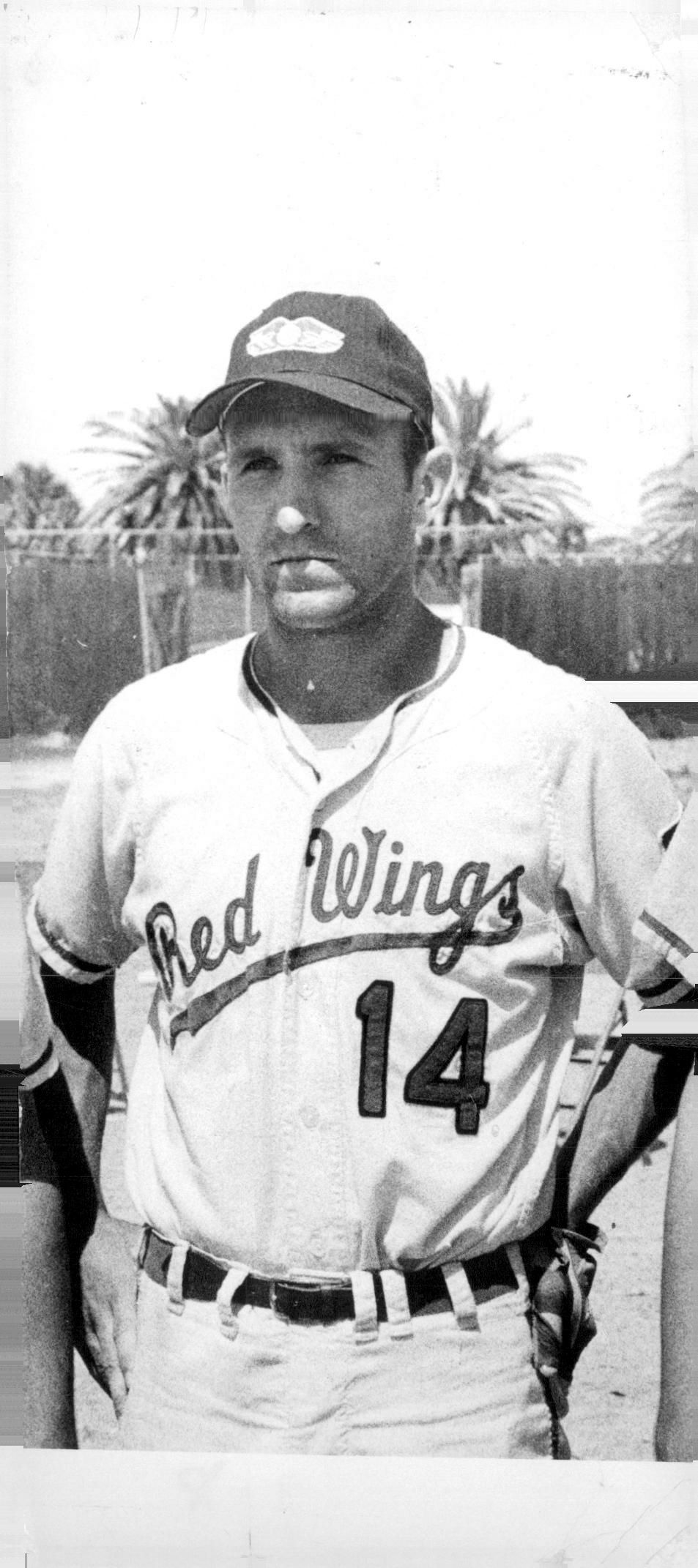

Indeed, Bull Durham is a film that Shelton was destined to make. He was born Ronald Wayne Shelton on September 15, 1945, in Whittier, California. A shortstop-second baseman, the 6-foot-1, 185-pounder was taken by the Baltimore Orioles in the 39th round of the 1966 major-league June Amateur Draft. From 1967 through 1971, he toiled in the bushes with the Stockton Ports, Bluefield Orioles, and Dallas-Fort Worth Spurs, topping out with the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings. His minor-league numbers were unspectacular: a .251 batting average in 479 games, with 425 hits in 1,691 at-bats.

As any baseball film aficionado knows, Bull Durham contrasts Crash Davis (Kevin Costner), an aging catcher for the minor-league Durham Bulls who during the course of the story breaks the bush-league record for career four-baggers, and Ebby Calvin “Nuke” LaLoosh (Tim Robbins), a raw rookie hurler famously described as possessing a “million-dollar arm, but a five-cent head.”7 The third major character – the one who cites Whitman and Blake – is Annie Savoy (Susan Sarandon), a sexy baseball groupie who each spring selects one Bull as a season-long lover.

Across the years all three have become iconic screen characters. In August 2015 Mike Hessman, a (mostly) career minor leaguer, belted his 433rd dinger, setting the all-time bush-league record. In report after report of the accomplishment, Hessman was referred to as the real-life Crash Davis, the modern-era Crash Davis. In fact, later that month, when his Toledo Mud Hens were playing the Durham Bulls, Hessman was presented with a framed Crash Davis jersey. “I don’t mind,” he declared. “I guess that’s me. It’s fun. It’s cool. And I have the record. It’s good to be known for something.”8

As for “Nuke” LaLoosh, the story goes that the character was inspired by Steve Dalkowski, otherwise known as “The Fastest That Never Was.” In the early 1960s Dalkowski pitched in the Baltimore Orioles farm system. Granted, he just may have been the hardest thrower ever, but he was unable to harness his control and never made it to “The Show”; the yarns Shelton heard about Dalkowski (whose career predated his) supposedly added to his creating the character.

However, in Fastball, the 2016 documentary written and directed by Jonathan Hock and narrated by Kevin Costner, it is noted that LaLoosh “was based in part on Dalkowski or Sidd Finch, George Plimpton’s imaginary pitcher who threw 168 miles per hour.”9 Twenty-eight years earlier, upon the film’s release, Shelton told the press, “All characters and fictional people are composites. Every team I played on had one or two wild young pitchers who could throw the ball through a brick wall, but never got the Zen aspects of the game together.”10

At the time, Greg Arnold, a pitcher who played with Shelton before retiring at age 22 in 1971, claimed that he was Shelton’s inspiration. “There was no other (‘Nuke’) LaLoosh,” he stated. “He (Shelton) knows it and I know it, and that’s all that really matters. He’ll go to bed in September with $4 million or $5 million, and I’ll go to bed knowing one thing – that I am the Nuke.”11 (In his career, Arnold appeared in 83 games, walking 315 batters and striking out 413 in 476 innings.)

Lastly, in one of the most oft-quoted passages from any baseball film, Annie Savoy professes her belief in “the Church of Baseball.” “I’ve tried all the major religions, and most of the minor ones,” she declares. “I’ve worshipped Buddha, Allah, Brahma, Vishnu, Siva, trees, mushrooms, and Isadora Duncan. I know things. For instance, there are 108 beads in a Catholic rosary and there are 108 stitches in a baseball. When I learned that, I gave Jesus a chance. But it just didn’t work out between us. The Lord laid too much guilt on me.

“I prefer metaphysics to theology. You see, there’s no guilt in baseball, and it’s never boring, which makes it like sex. There’s never been a ballplayer slept with me who didn’t have the best year of his career.”12

Annie Savoy and her super-fandom aside, in Bull Durham Shelton conjured up a knowing ode to minor-league baseball and baseball players, not to mention the pressures faced by wannabes who yearn for their shot in “The Show.” The underlying point here is that, in the end, pro sports is a business. “It’s about the players as people, the very real pressures they face,” he noted. “For example, are they gonna get promoted? Are they gonna lose their jobs?”

Undeniably, the film’s enduring popularity has reverberated across the decades. One of countless examples: On May 28, 2016, New York Post columnist Kevin Kernan casually observed, “Earlier this year, Noah Syndergaard said his pitching world changed for the better over the past year when he finally learned how to loosen his grip on the baseball and hold it like an egg, as they explained in the movie Bull Durham.”13

The film also has transcended the sports page, and has come to define Shelton’s show-biz success. In 2010 TBS announced that he had signed to write and executive-produce the Bull Durham-esque Hound Dogs, an hourlong TV comedy pilot centering on the minor-league Nashville Hound Dogs. “As he did with Bull Durham, Shelton will draw from his own experiences as a minor leaguer,” reported Entertainment Weekly.14 But the show was not picked up, and Hound Dogs emerged as a 2011 made-for-television movie.

Then in 2013, the Topps Pro Debut baseball card set featured Bull Durham cut signature cards of Costner, Sarandon, Robbins, and Robert Wuhl (who plays Coach Larry Hockett); three years later, the Topps Archives set included seven Bull Durham insert cards along with autographed cards of Shelton and various cast members. The property also was transformed into a stage musical, which premiered in Atlanta in 2014. Shelton contributed the show’s book; the essence of the story is summed up in the three-sentence description found on the show’s website: “CRASH loves Annie. NUKE loves Annie. ANNIE loves Baseball.”15

Then in 2016, he was co-executive producer (along with Eric Gagne and Ben Lyons) of Spaceman, a biopic directed by Brett Rapkin and starring Josh Duhamel as Bill “Spaceman” Lee.

Back in the 1990s, while researching the book Great Baseball Films, I queried real-life major leaguers on their feelings toward baseball-on-screen. Phil Rizzuto commented that those who truly know the game should be hired for their expertise. “They should have ex-ballplayers, groundskeepers (and) newspapermen to make (the films more) realistic,” pronounced Scooter.16

Rizzuto easily might have cited Ron Shelton as the ideal baseball-movie architect. So it was not surprising that Bull Durham was lauded by baseball professionals. “I thought it was a great movie,” Don Mattingly told me in a Yankee Stadium pregame conversation. “I played in the South Atlantic League, (and the film) was pretty close to capturing life in the minor leagues. It was pretty cool.”17 “When it came out,” reported Shelton, “Will Clark (then of the San Francisco Giants) was passing out garter belts in the locker room. Apparently, the Giants really embraced the movie.”

Even the comments that were more critical at least acknowledged the film’s uniqueness. “The most true-to-life (baseball films) have been made in recent years,” observed Joe L. Brown, the son of comic actor Joe E. Brown and the longtime Pittsburgh Pirates general manager, who was interviewed for Great Baseball Films. “Bull Durham was good, but I didn’t like all the profanity. Some of the incidents in it seemed outlandish, but there was truth to it as it showed some of the experiences kids have in the lower minor leagues.”18

Shelton’s reason for making Bull Durham, he explained, was that he “felt no one had made a sports movie right.” The majority of baseball films focus on the glory of the game, on-field drama, underdog heroes hitting game-winning home runs in the last of the ninth or striking out a fearsome opponent’s heaviest hitter with the bases loaded. “I generally don’t like them,” he noted. “They’re not relative to anything other than a publicist’s idea of their subjects.”

For example, Shelton cited two celluloid biographies of Babe Ruth: The Babe Ruth Story, a 1948 film starring William Bendix; and 1992’s The Babe, with John Goodman. “Neither of them worked,” he said. “The first in particular is nothing more than a campy exercise. How can you believe William Bendix, who looked to be about 45 when he made this film, in his scenes (playing Babe) as a 16-year-old orphan?”

He added that fans “don’t understand that athletes don’t hate other athletes. The Dodger players don’t hate the Giant players. The fact of the matter is that they all hate management. They all have much in common with labor.

“My view of sports is from the field, the locker room, the team bus. I tend to tell stories from the field, not the 30th row of the bleachers.” With this in mind, Shelton was ideally suited to direct Jordan Rides the Bus (2010), a 51-minute episode of 30 for 30, the ESPN documentary series. There, he charts Michael Jordan’s early 1990s foray into minor-league baseball.

Shelton’s approach remains consistent in the nonbaseball films he has directed and scripted: White Men Can’t Jump (1992), the story of two urban basketball hustlers (Woody Harrelson and Wesley Snipes); Tin Cup (1996), about a self-destructive golfer (also played by Kevin Costner); and Play It to the Bone (1999), with Harrelson and Antonio Banderas as aging boxers and best pals who agree to face off in the ring. Sports also are present in films that Shelton only scripted or co-scripted: football (1986’s The Best of Times); basketball (1994’s Blue Chips); and boxing (1996’s The Great White Hype).

However, even when baseball is not the focus of the story, Shelton manages to sneak references to the sport into his scenario. For instance, in Tin Cup, it is revealed near the finale that the hero, Roy “Tin Cup” McAvoy, won his nickname as a schoolboy baseball player. In one sequence, McAvoy even yells out “Louisville Slugger” as he belts a golf ball with a baseball bat.

In his earliest films, Shelton is credited only as screenwriter. He was inspired to work behind the camera because, as he explained, “I wanted to direct my own words. I didn’t like the way they’d been interpreted on screen.” One exception is Under Fire, whose script Shelton co-authored with Clayton Frohman: a 1983 drama set in Nicaragua just before the fall of dictator Anastasio Somoza to the revolutionary Sandinista forces. “I was pleased with the way that one was made,” Shelton said.

One of the secondary characters in Under Fire is Pedro, a bomb-throwing Sandinista who greatly admires then-Baltimore Orioles pitcher Dennis Martinez. Pedro autographs a baseball and instructs an American reporter to give it to Martinez when she returns to the United States. With a grand gesture, he dons an Orioles cap and hurls a grenade with pinpoint accuracy, just as his idol would burn in fastballs.

“Kid’s got a hell of an arm,” observes a photojournalist. Pedro then declares, “Dennis Martinez, he is the best. He is from Nicaragua. He pitches major leagues. … You see Dennis Martinez, you tell him that my curveball is better, that I have good scroogie. …”19 Seconds later, Pedro is felled by a bullet.

“I didn’t want to make an ideological movie about the Nicaraguan revolution,” explained Shelton. “I didn’t want to make a movie for the already converted. But how could I make the Sandinista point of view understandable to audiences? I decided to do it through baseball, by having a young revolutionary infatuated with baseball.” Pedro is a character who, as Shelton said, “is not gonna talk about Karl Marx. He’s gonna talk about Earl Weaver.”

In Under Fire, Shelton honors the type of little-known but devoted ballplayer with whom he feels an affinity by naming one of the characters, a political flack, after career minor-league pitcher-manager Hub Kittle. Kittle entered baseball as a player in 1937 and began managing in 1948, but kept returning to the mound for years after his final full season as a pitcher. In 1980, at age 63, he even hurled an inning for the Triple-A Springfield Redbirds. (Kittle finally debuted in the majors in 1971, as a Houston Astros coach.)

Hub Kittle may be a relatively obscure baseball professional. Ty Cobb may be one of the most famous names in baseball history. But which one would you rather have coaching your kid’s Little League baseball team?

Still, Bull Durham – and not Cobb or any of his other films – remains Ron Shelton’s masterpiece. Upon its release, I described it as “a tremendously entertaining film and arguably the most knowing of all baseball movies.”20 This was true in 1988, and it remains so in 2016.

ROB EDELMAN is the author of Great Baseball Films and Baseball on the Web (which Amazon.com cited as a Top 10 Internet book), and is a frequent contributor to Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game. He offers film commentary on WAMC Northeast Public Radio and is a longtime Contributing Editor of Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide and other Maltin publications. With his wife, Audrey Kupferberg, he has coauthored Meet the Mertzes, a double biography of Vivian Vance and super-baseball fan William Frawley, and Matthau: A Life. His byline has appeared in Total Baseball, The Total Baseball Catalog, Baseball and American Culture: Across the Diamond, NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History, The Baseball Research Journal, and histories of the 1918 Boston Red Sox, 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers, 1947 New York Yankees, and 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates. He is the author of a baseball film essay for the Kino International DVD Reel Baseball: Baseball Films from the Silent Era, 1899-1926; is an interviewee on several documentaries on the director’s cut DVD of The Natural; was the keynote speaker at the 23rd Annual NINE Spring Training Conference; and teaches film history courses at the University at Albany (SUNY).

Photo credit

Ron Shelton with the Rochester Red Wings. (Courtesy of the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle)

Author’s note and acknowledgments

The original version of this article was published in 1997 in Issue 17 of SABR’s The National Pastime.

Special thanks to Rory Costello and John-William Greenbaum for their comments on the “origin” of “Nuke” LaLoosh.

Notes

1 Earl Gustkey, “Ty Cobb: No Better Player Swung a Bat; No Worse a Person Played the Game,” Los Angeles Times, September 12, 1985.

2 All remarks from Ron Shelton are from an interview conducted by the author in December 1994, unless otherwise indicated.

3 Al Stump, Cobb: A Biography (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1994), 6.

4 Research by Pete Palmer resulted in two base hits – which had been double-counted – being subtracted from Cobb’s career batting average, edging it down from .367 to .366.

5 https://rollingstone.com/movies/reviews/cobb-19941202.

6 https://sfgate.com/movies/article/FILM-REVIEW-Tommy-Lee-Jones-Strikes-Out-as-3028597.php

7 Line from Bull Durham screenplay.

8 Johnette Howard, “Minor League HR King Mike Hessman – the Real-Life Crash Davis – Had Career Worth Celebrating,” ESPN.com, December 14, 2015.

9 Line from Fastball narration.

10 Mark Hyman, “No Bull: Ex-Player Claims He Inspired ‘Durham’ Character,” Daytona Beach Sunday News-Journal, July 3, 1988: 5D.

11 Ibid.

12 Lines from Bull Durham screenplay.

13 Kevin Kernan, “Get Michael Pineda Out of Yankees Rotation Right Now,” New York Post, May 28, 2016.

14 Mandi Bierly, “Ron Shelton to Pen Minor League Baseball Comedy for TBS. Can We Call Up Costner (or Russell)?” Entertainment Weekly, October 21, 2010.

15 https://bulldurhammusical.com/

16 Rob Edelman, Great Baseball Films (New York: Citadel Press, 1994), 10

17 On-field pregame interview with author at Yankee Stadium, July 1994.

18 Edelman.

19 Lines from Under Fire screenplay.

20 Edelman.