Talking baseball research with Herm Krabbenhoft

This article was written by Bill Lamb

This article was published in SABR Deadball Era newsletter articles

This article was originally published in the November 2018 edition of “The Inside Game,” the SABR Deadball Era Committee newsletter. Since February 2015, The Inside Game has had the privilege of publishing Herm Krabbenhoft’s record-revising research into the accuracy of Deadball Era statistics. Herm’s work on stats long predates his association with the newsletter, and is recognized throughout the baseball research community for its thoroughness, reliability, and scrupulous attention to detail. Modern authorities, including the Elias Sports Bureau, the official keeper of MLB records, have often revised their statistics to incorporate the latest Krabbenhoft findings. Recently, Herm responded to questions about his life and work posed by newsletter editor Bill Lamb.

Q: Herm, thanks for agreeing to the interview. Why don’t we start with a thumbnail self-portrait?

Q: Herm, thanks for agreeing to the interview. Why don’t we start with a thumbnail self-portrait?

A: Born in Detroit, on July 15, 1945, the same day that the Tigers’ Zeb Eaton slugged a pinch-hit grand slam homer against the Yankees. Fittingly, Detroit also won the World Series that year. I attended Wayne State University (BS Chemistry, 1970), the University of Michigan (Ph.D Organic Chemistry, 1974), and was a National Institutes of Health Post-Doctoral Research Award Fellow at the University of California-Berkeley from 1974-76. I am now a retired research chemist, after working for General Electric for 25+ years, mostly at their Corporate Research & Development Center in Schenectady, New York, primarily in the areas of synthetic organic and polymer chemistry.

My first game: May 20, 1956, Briggs Stadium; Tigers swept a doubleheader from Washington; first home run: a first-inning grand slam by Bill Tuttle in the second game. Best game: Game Five, 1968 World Series, Tiger Stadium: Willie Horton threw out Lou Brock at the plate to stifle a St. Louis rally in the fifth inning and Al Kaline hit a seventh-inning two-run single to put Detroit in the lead. My Tigers were never behind again in the rest of the World Series.

Other interests: playing racketball; building different track layouts to run my Ogauge model trains (12’ x 8’ footprint); reading about Great Lakes ships.

Q: Your research has covered a broad range of baseball topics, but newsletter readers probably best know you from your articles about the accuracy of baseball statistics. How did that interest originate?

A: Accuracy is important, whether it be with one’s checkbook, mixing chemicals, or working with baseball’s numbers. The articles I’ve written on achieving accurate full-season runs-scored and runs-batted-in numbers are by-products from my research to ensure that I have access to accurate numbers on a game-by-game basis — because my primary objective is to ascertain the longest Consecutive Games Run Scored (CGRUNS) streak and the longest Consecutive Games Run Batted In (CGRUNBI) streak for each Detroit Tigers player.

My interest in these streaks goes back to 1961 when I picked up my first Little Red Book of Baseball and was intrigued with the AL and NL records for the longest CGRUNS streak [at that time shown (incorrectly) to be 19 games by Nellie Fox (1954 White Sox)] and the longest CGRUNBI streak, at that time shown (incorrectly) to be 11 games by Mel Ott (1929 Giants). I wondered what the records were for the Detroit Tigers. And while I wondered about that from time to time over the years, I didn’t do anything to find out. Then, when on-base average became truly recognized as being more important than batting average, I got the bug to ascertain who had the longest Consecutive Games On Base Safely (CGOBS) streak, i.e., the counterpart to Joe DiMaggio’s famous 56-game hitting streak.

After I had completed that research (in 2002) and determined that Ted Williams assembled the longest CGOBS streak — an 84-gamer in 1949, I started my quest to find the longest CGRUNS and CGRUNBI streaks for players on the Detroit Tigers, from the present all the way back to 1901. At first, I thought it would be an easy-to-do research project — just go through the official Day-By-Day (DBD) records. But I didn’t want just the bare numbers; I also wanted some perspective. So I checked the relevant game accounts in the various newspapers and was surprised to find that here and there were errors in the official records.

Thus, I realized that I could not blindly accept what was shown in the official DBD records — I had to verify the CGRUNS and CGRUNBI streaks. And, in doing the verifications I discovered more errors. But, the errors, when corrected, not only impacted the CGRUNS and CGRUNBI streaks, the full-season runs-scored and runs-batted-in numbers were also affected. Correcting full-season runs-scored and runs-batted-in numbers has never been the primary objective in my Deadball Era research. But it is an important derivative from accurately ascertaining the longest CGRUNS and CGRUNBI streaks.

Q: Gathering reliable statistical information about games played perhaps a century ago has to be a challenge. How have you dealt with that problem? And have you ever encountered an information-gathering challenge(s) that proved insurmountable?

A: Answer for the first part of the question: To get reliable information about any game, one has to check out the game accounts provided in multiple independent newspapers. Initially, I focused on the New York Times and The Sporting News. But, I learned that for my Detroit Tigers research, I really needed the Detroit newspapers — Free Press, News, and Times — as well as newspapers published in the city of the opposing team — especially if the game was played in the opposing team’s ballpark. So I’ve spent a lot of time going through microfilmed newspapers in a number of libraries.

Since I lived in upstate New York, I was reasonably close to the New York State Library and the libraries at Cornell and Harvard, each of which has an excellent newspapers-on-microfilm collection. And, because I would get back to Michigan to visit family now-and-then, I would allocate time to get to the Detroit Public Library. And, I’ve gone to many other libraries, such as the public libraries in Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, etc., as well as the Library of Congress.

For instance, when SABR had its annual convention in Philadelphia, I flew in three days early so I could “camp out” at the Free Library of Philadelphia to get photocopies and/ or scans of the game accounts for the 1895 Phillies from several newspapers (Inquirer, North American, Press, Public Ledger, and Record.) I wanted to ascertain accurate game-by-game RBI numbers for Sam Thompson since the various baseball encyclopedias show him with 165 RBIs (in 119 games). I also ascertained accurate game-by-game RBI numbers for him with the 1887 Detroit Wolverines (166 RBIs in 127 games).

And while I have done a lot of the library work myself, I can’t get everything that I need by myself — I need help, sometimes a lot of help. And the SABR community has always been very helpful for me. I particularly want to mention and again thank the following people who have been of enormous help to me many, many times — Cliff Blau, Steve Boren, Keith Carlson, Bill Deane, Steve Hirdt, Ralph Horton, Bob McConnell, Trent McCotter, Art Neff, Dave Newman, Pete Palmer, Tom Ruane, Seymour Siwoff, Dave Smith, Jim Smith, Gary Stone, Dixie Tourangeau, and David Vincent.

There have been many others who have helped me over the years and I have gratefully acknowledged them in my articles and presentations. There is also a collective group of people who have been a huge help to me indirectly — the Retrosheet volunteers. THANKS to them there is the phenomenal Retrosheet database. As I have stated numerous times, Retrosheet is a Baseball Research Enabler! — thanks to the dedicated Retrosheet volunteers.

Answer for the second part of the question: Unfortunately, there are some instances where the requisite details are not provided in any of the newspaper game accounts. For example, for the Tigers-Browns game on April 11, 1913 in St. Louis, Detroit scored two runs in the eighth inning. The text description given in the game account published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat states, “With Vitt out in the eighth, Crawford, Gainer, Moriarty, and Deal singled in rotation, Crawford scoring and leaving the bases still packed. Louden fouled to Agnew, but when Hamilton cut loose a wild pitch, allowing Gainer to score, [manager] Stovall took Hamilton out and sent in Baumgardner.”

This description does not state specifically whose single batted in Crawford — i.e, Did Moriarty’s single drive in Crawford (from second or third) OR advance him to third from where he scored on Deal’s single? The text descriptions given in several other newspapers (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Republic, and Star-Times and Detroit Free Press, Journal, News, and Times) were similar in that none of them stated specifically who batted in Crawford — Moriarty or Deal.

The consequence of this uncertainty is that for the entire season, Moriarty achieved 28 or 29 RBIs and Deal achieved 2 or 3 RBIs. As it has developed, there have been one or two or three of these “either-or” situations in some of the seasons examined in my Deadball Era RBI research.

Q: For me, your demonstration that Heinie Zimmerman did, in fact, capture the NL Triple Crown in 1912 (Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2015) was eye-opening and persuasive. What do you personally regard as your most significant statistical discovery or revision?

Q: For me, your demonstration that Heinie Zimmerman did, in fact, capture the NL Triple Crown in 1912 (Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2015) was eye-opening and persuasive. What do you personally regard as your most significant statistical discovery or revision?

A: Yeah, resolving the 1912 NL RBI crown discrepancy, thereby showing that Zimmerman won the Triple Crown, is pretty significant. Similarly, the research that Keith Carlson, Dave Newman, Dixie Tourangeau, and I did to resolve the discrepancy surrounding Billy Hamilton’s record for the most runs scored in a single season is significant. Likewise, the research we did to address the uncertainty surrounding the 1894 RBI champion. Also, the research I did with Jim Smith and Steve Boren to assemble an accurate and comprehensive database of Triple Plays is significant. And the research I did to ascertain accurate RBI records for Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Hank Greenberg. Also, when I began the research (in 1987, i.e., 7 years before Retrosheet began), ascertaining all of the players who hit Ultimate Grand Slam Homers throughout the history of MLB and identifying the Principal Leadoff Batters for each team for each season from 1900 forward were significant research advances at the time.

Q: If I understand correctly, prior to publication you often transmit your findings to Dave Smith and Tom Ruane of Retrosheet for review and confirmation. How does that process work?

A: The 1909 season provides, I believe, a good illustration of the process. When Retrosheet released its box score file for the 1909 season, 66 of Detroit’s 158 games had no RBI statistics — the RBI columns were blank. From my independent research I had assembled complete information on each of the 666 runs the Tigers tallied, my runs-scored and RBI numbers having been obtained from the game accounts presented in four Detroit newspapers (the Free Press, Journal, News, and Times) as well as at least one game account from a newspaper from the city of the opposing team for games played at the opponent’s ballpark.

As a result, I knew for each of the 666 runs: (a) who scored, (b) how he scored, and (c) who, if anyone, batted him in. So, I put together a report (“Retro Report A”) in which I presented the verbatim text descriptions (from the game accounts provided in the multiple newspapers) of each run scored by the Tigers for each of the 66 games for which the Retrosheet box score did not have RBI statistics.

In addition, there were 14 games for which from my research I came up with different RBI numbers compared to those in the Retrosheet box scores. I put together an analogous report (Retro Report B”) for these 14 games. I provided these “Retro Reports” to Tom and Dave, and after reviewing the evidence I had assembled, we achieved 100% concurrence for the runs and RBIs. Thereafter, Retrosheet incorporated the additions and changes in their box scores (and derived player daily files). It may be added that I also discovered three games with erroneous home run information in the SABR Home Run Log. I provided the supporting documentation to Tom and Dave. They concurred with my findings and passed the corrections on to SABR.

Then, with independent corroboration of my runs-scored and runs-batted-in numbers by Retrosheet, I proceeded to draft my manuscripts — (a) the “1909 Detroit Tigers Accurate Runs-Scored” article appeared in the June 2018 issue of The Inside Game; (b) the “1909 Detroit Tigers Accurate Runs-Batted-In” article appeared in the September 2018 issue of The Inside Game.

We used the exact-same process for the 1919-1907 seasons. The process is a win-win — altogether for the 1919-1907 seasons, when Retrosheet first posted the box scores for the Tigers, there were 703 games with missing RBIs. After executing the review process, there are now only 24 “missing-RBIs” games. And, because there are many other team-seasons with missing RBI numbers (more than 1,600 in the NL and almost 2,300 for the AL), I heartily encourage others join the effort.

Q: Your research has often led to findings which alter current stats. And on occasion, these new statistics have led to a changing of a league leader in runs scored, RBIs, etc.: the numbers change and/or a new league leader is identified. In such instances, have your findings been communicated to Elias, and, if so, has baseball’s official record-keeper adopted those findings?

A: Yes, over the years I have communicated my findings to Elias. In many (most, but not all) cases, Elias has officially sanctioned the corrections — for instance, “The Authorized Correction of Errors in Runs Scored in the Official Records (1945-2007) for Detroit Tigers Players” [Baseball Research Journal, 2008] and “The Authorized Correction of Errors in Runs Scored in the Official Records (1920-1944) for Detroit Tigers Players” [Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2011]. Subsequently, I published a follow-up article, “Additional Corrections in the Official Records (1920-1944) of Runs Scored for Detroit Tigers Players” [Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2013].

Altogether, in my research on the 1920-2007 period I discovered and corrected 85 runs-scored errors in the official records for 54 different players — including Hall of Famers Cobb, Gehringer, Goslin, Greenberg, Kaline, Kell, Manush, and Newhouser. The most significant corrections reported in these articles are: (a) Charlie Gehringer actually led the AL in runs scored in 1934 with 135 (not 134); (b) Hank Greenberg actually led the AL in runs scored in 1938 with 143 (not 144). Elias has accepted the former, but not the latter. Retrosheet has accepted both. And so has Pete Palmer, and therefore, Baseball-Reference (which uses Palmer’s database of baseball statistics) shows Greenberg as the 1938 AL runs-scored leader with 143.

For the past several years my focus has been on the Deadball Era (1901-1919), primarily the players on the Detroit Tigers (although I’ve also investigated the 1919 Red Sox, the 1917 White Sox and Giants, and the 1912 Braves, Cubs, Giants, and Pirates). For the 1906-1919 Tigers, I’ve discovered and corrected 71 runs-scored errors in the official records for 34 different players (including Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford).

Perhaps the most significant runs-scored error I’ve discovered and corrected (thus far) for the Deadball Era Tigers is the one for Donie Bush in the 1909 season — the official records credit him with 114 runs, while my research [reported in The Inside Game in June 2018] proves that he actually scored 115 runs. The significance is that the 2003-2018 editions of The Elias Book of Baseball Records show Ty Cobb as the sole 1909 AL leader in runs scored with 115. (Prior to the 2003 edition, Cobb was shown with the incorrect total of 116 runs, i.e., the number given in his official DBD records.) Thus, Bush actually was a co-leader in most runs scored in the AL in 1909.

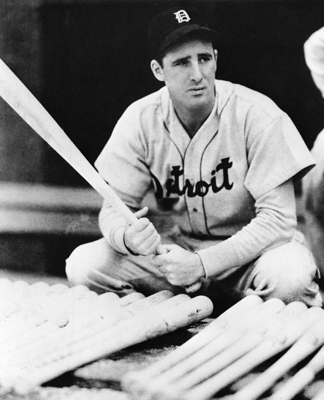

I have provided all of the supporting documentation to Seymour Siwoff and Steve Hirdt at Elias. We’ll see what happens. Retrosheet has already concurred with my findings and when one adds up all of Bush’s runs as shown on Retrosheet’s Player Daily file for him, the sum is 115 runs; likewise for Cobb. With regard to the correction of RBI errors in the official records, probably the most interesting are those involving the RBIs achieved by Hank Greenberg in 1937 and by Lou Gehrig in 1931. According to the official DBD records, Greenberg had 183 RBIs in 1937 and Gehrig had 184 in 1931. Trent McCotter and I collaborated on researching Greenberg’s RBI record for 1937. We found that Greenberg actually had 184 RBIs in 1937 and presented our findings at the SABR 41 convention in Long Beach, California. Subsequently, we researched Gehrig’s RBI record for 1931 and found that Gehrig actually had 185 RBIs in 1931.

I have provided all of the supporting documentation to Seymour Siwoff and Steve Hirdt at Elias. We’ll see what happens. Retrosheet has already concurred with my findings and when one adds up all of Bush’s runs as shown on Retrosheet’s Player Daily file for him, the sum is 115 runs; likewise for Cobb. With regard to the correction of RBI errors in the official records, probably the most interesting are those involving the RBIs achieved by Hank Greenberg in 1937 and by Lou Gehrig in 1931. According to the official DBD records, Greenberg had 183 RBIs in 1937 and Gehrig had 184 in 1931. Trent McCotter and I collaborated on researching Greenberg’s RBI record for 1937. We found that Greenberg actually had 184 RBIs in 1937 and presented our findings at the SABR 41 convention in Long Beach, California. Subsequently, we researched Gehrig’s RBI record for 1931 and found that Gehrig actually had 185 RBIs in 1931.

All the supporting documentation was provided to Elias, as well as to Dave Smith, Tom Ruane, and Pete Palmer. Elias has chosen to not adopt the corrections; Retrosheet and Palmer have adopted the corrections. Thus, in the 2018 edition of The Elias Book of Baseball Records, Gehrig is still shown as the 1931 AL RBI leader with 184 (which is also given as the AL record for the most RBIs in a single season) and Greenberg is still shown as the 1937 AL RBI leader with 183. However, Retrosheet and Baseball-Reference show Gehrig as the 1931 AL RBI leader with 185 and Greenberg as the 1937 AL RBI leader with 184.

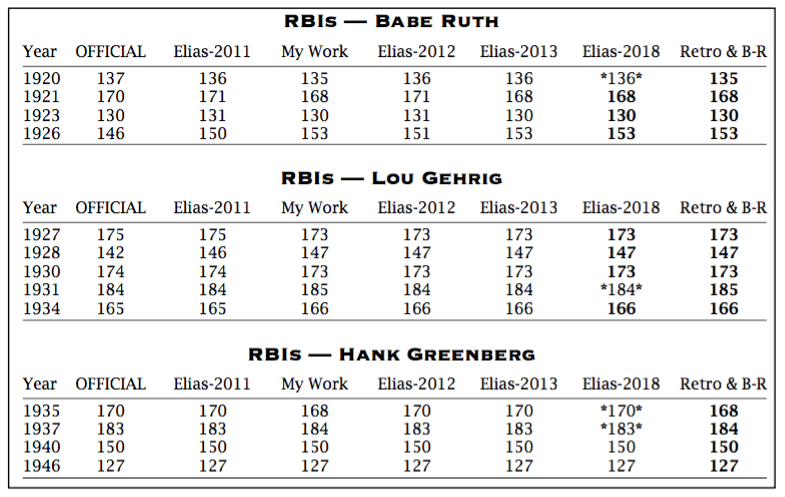

Closely related to these single-season researches are the investigations I carried out to ascertain accurate career RBI numbers for Babe Ruth [Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2013], Lou Gehrig [Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2011, Fall 2012], and Hank Greenberg [Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2012]. I found RBI errors in the official records for several seasons in which each was the AL leader in RBIs. The chart below summarizes what corrections have been adopted (and when) and what corrections have not (yet) been adopted by Elias.

(Click image to enlarge.)

Of the 13 seasons shown, my research came up with different RBI numbers than Elias for 11 seasons; the only seasons where my RBI numbers agreed with Elias’s RBI numbers were 1940 and 1946. Of the 11 seasons with different RBI numbers, Elias has subsequently adopted my RBI numbers for 7 of the seasons (indicated by the “Elias-2018” column entries being shown in boldface). Retrosheet and Baseball-Reference, however, have adopted my RBI numbers in each of the 11 seasons (all entries shown in boldface).

For some reason (unknown to me) Elias has not adopted my corrections for the 1920, 1931, 1935, and 1937 seasons (indicated by the “Elias-2018” column entries being bracketed with asterisks). Since RBIs were not recorded officially prior to 1920, Elias does not even recognize the unofficial pre-1920 RBI numbers ascertained by Ernie Lanigan, David S. Neft, Retrosheet, myself, or anybody else.

Neft’s RBI numbers for pre-1920 seasons [first presented in The Baseball Encyclopedia, published by Macmillan in 1969, and subsequently incorporated in the baseball databases of Pete Palmer and STATS] seem to be considered “like-official” as they are the RBI numbers that are shown “everywhere” — i.e., in Total Baseball, The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia, and on the Internet (such as the Baseball-Reference website), etc. In conducting my research to obtain accurate game-by-game RBI records for the players in the Deadball Era, I have found that my full-season RBI numbers differ from Neft’s full-season RBI numbers for most of the players, typically about two-thirds of all the players and oftentimes for three-quarters or more of the full-time players.

Since Neft’s game-by-game records are not extant, it is not possible to determine the sources of our differences. That my RBI numbers are correct is supported by the fact that Retrosheet’s Tom Ruane and Dave Smith have concurred with my RBI numbers and incorporated them into the Retrosheet box scores (and the derived player daily files).

Q: As previously mentioned, your research has not been confined to statistics. For example, you published an informative and entertaining account of the career of Yale first baseman/captain George H.W. Bush (Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2017). You also wrote an article about President Bush’s playing days years ago for USA Today. Where did this interest come from?

A: In 1988, in doing my research on the Principal Leadoff Batters for the 1948 season, I utilized the box scores presented in the New York Times — I recorded the leadoff batter for each team for each game, his at-bats, runs, and hits. On the front page of one of the Sunday Sports sections was the now iconic photo of Babe Ruth (in civilian clothes) presenting the manuscript of his autobiography to a Yale baseball player. It grabbed my attention and I read the photo caption and learned that the Yale player was George Bush.

Since at that time Bush was the Vice President (and would become the President) of the United States, I thought it would be a neat research project to ascertain his complete collegiate baseball record. So, it was one of those “research begets research” efforts. And, over the next several months I did the research, making a couple trips to New Haven, Connecticut, to check out the relevant articles in the Yale Daily News at the Yale Library, as well as the game accounts published in the New Haven Evening Register at the New Haven Public Library.

I wrote my article, “George Herbert Walker Bush — Iron Man First Sacker at Yale,” for the Fall-1989 issue of Baseball Quarterly Reviews, a self-published baseball research journal which I did from 1986 through 1996. Then, in 1991, in the premiere issue of Baseball Weekly was an article about President Bush’s Yale baseball career. Based on my findings, much of the statistical information provided in the article was incorrect. I wrote to Baseball Weekly and provided my research results. Baseball Weekly then ran an article (with no byline) titled, “Baseball Expert Challenges Yale Stats on ‘Poppy’ Bush.”

The Yale assistant sports information director, Sara Hoffman, stated in the article that if their stats are wrong, they would change them. After that I went on with my other research endeavors and pretty much forgot about my “Bush research.” Then, some 26 years later I chanced upon a January 2015 Yale press release focused on Bush’s Bulldog diamond career in conjunction with preparations to celebrate Yale’s sesquicentennial season. I was surprised (and disappointed) that there were still many errors for Bush’s statistics.

So I decided it was appropriate to present my “Bush research” in a vehicle with a greater audience than which my BQR had. I repackaged my BQR article and submitted it for consideration for publication in the Baseball Research Journal. The reviewer reports came back with the strong message that, while accurate statistics are important, for the article to be publishable in the BRJ, it needed more biographical stuff. So now, in 2017, with the power of the Internet, I came up with an abundance of baseball-connected biographical information on George H.W. Bush. The revised manuscript was accepted and published.

Q: Your articles for The Inside Game have frequently focused on the stats of the Deadball era Detroit Tigers. Ty Cobb, the star of that club, has recently been the subject of several new bios. What is Dr. Krabbenhoft’s diagnosis of The Georgia Peach: a typical ballplayer of his times; psychopath, misunderstood perfectionist; overly sensitive Southerner; none of these?

A: I haven’t read any of those recent Cobb biographies. Several years ago I bought and read Charles Alexander’s biography of Cobb when I was doing my research on “Ty Cobb vs. Babe Ruth — Premier Hitter vs. Premier Pitcher (BQR, Spring 1987). I don’t have a diagnosis of Cobb’s character. One thing that I’ve wondered about, though, is: Just how beneficial was Cobb’s aggressiveness on the basepaths? In doing my Deadball Era research, I’ve come across several instances where “The Genius in Spikes” scored from first on a single or from second on a groundout. But, I’ve also seen several instances where he was put out at the plate trying to score on these daring (reckless?) dashes.

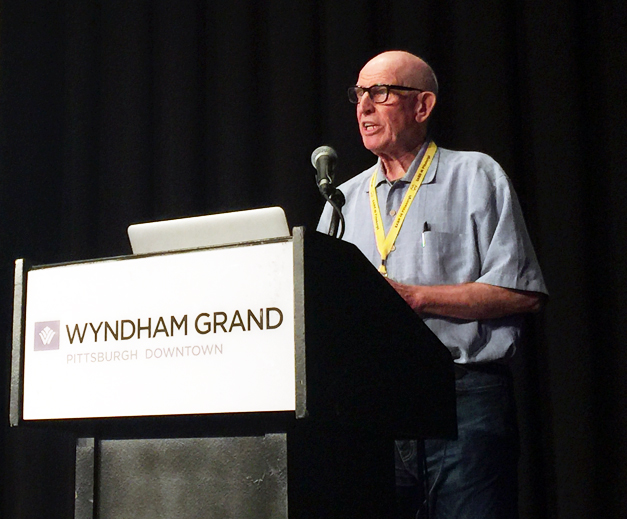

Q: You have frequently been a presenter at the SABR convention, the annual conference of the 19th Century Committee, and other SABR events. Does any one presentation stand out in your mind as particularly memorable or enjoyable? If so, tell us about it.

A: The SABR convention presentation that is especially memorable for me was the one I gave at SABR 32 in Boston (2002). I presented my findings on CGOBS streaks and announced that Ted Williams’s 84-gamer in 1949 is (almost certainly) the MLB record.

A: The SABR convention presentation that is especially memorable for me was the one I gave at SABR 32 in Boston (2002). I presented my findings on CGOBS streaks and announced that Ted Williams’s 84-gamer in 1949 is (almost certainly) the MLB record.

I received a lot of very positive feedback on my research — in which I also discovered an error in Williams’ 1941 official record: in the first game of a doubleheader on September 24, the official records show that Williams went hitless in three (3) at-bats with no walks and that he was not hit with any pitched balls, thereby terminating his 64 CGOBS streak.

My research proved that, in actuality, Williams walked twice in the game, which thereby kept his CGOBS streak alive and which he extended to a “living” 69-gamer by the end of the season. He then got on base safely in each of the first five games of the 1942 season, giving him a “two-season” CGOBS streak of 74 games, which “equaled” Joe DiMaggio’s single-season 74- gamer.

Bill Nowlin wrote a nice article about my walks discovery for the SABR 32 convention journal — “Good Eye Leads to Two More Walks for Ted.” And Lyle Spatz included a nice comprehensive summary of my walks discovery in the June 2002 newsletter of the SABR Baseball Records Committee — “An Error Discovered in Ted Williams’s 1941 Walk Total.” Then, in June 2003, Seymour Siwoff sent me a nice note commending me on finding the walks error; he included a complimentary copy of The Elias Book of Baseball Records — which showed that Elias had made the correction for Williams’s two additional walks in 1941, i.e. he was now shown as the AL leader with 147 (not 145) walks.

Q: Who is your favorite Deadball Era player, and why?

A: Bobby Veach. He was an RBI machine for the Tigers. He became a full-time player in 1913 and placed third in RBIs among his teammates with 65 or 66 ribbies (not 64 as claimed by Neft). In 1914, he placed second with 77-79 RBIs (not 72). In 1915 Veach was either first or second with 114 or 115 RBIs (not 112). Crawford was also either first or second with 114-118 RBIs (not 112). From 1916 through 1919 Veach was the team leader with 89-90 (not 91), 110-114 (not 103), 84 (not 78), and 97 (not 101), respectively.

Moreover, Veach topped the AL in runs batted in for the 1918, 1917, and (perhaps) 1915 seasons. Significantly, Veach also had the most total RBIs in MLB for the 1913-1919 seasons — 641 (not 621); next in line were Gavy Cravath (595); Heinie Zimmerman (543); Ty Cobb (527); Del Pratt (497); Tris Speaker (493); Frank Baker (474); Joe Jackson (474); Eddie Collins (464); Sherry Magee (463). Disappointingly and shockingly, Veach has not (yet) been elected to the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame.

Q: Select your Deadball Era all-star team (with a five-man pitching staff, three reserves, and a manager).

A: Well, the outfield is easy — Cobb, Crawford, and Veach. For the infield, I’ll take the Hall of Famers Frank Chance, Eddie Collins, Frank Baker, and Honus Wagner. The catcher would be Roger Bresnahan. The five pitchers would be Walter Johnson, Pete Alexander, Christy Mathewson, Eddie Plank, and Ed Walsh. The three reserves would be Tris Speaker, Joe Tinker, and Joe Jackson. And the manager would be John McGraw.