The Babe: In Person and On Screen

This article was written by Rob Edelman

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

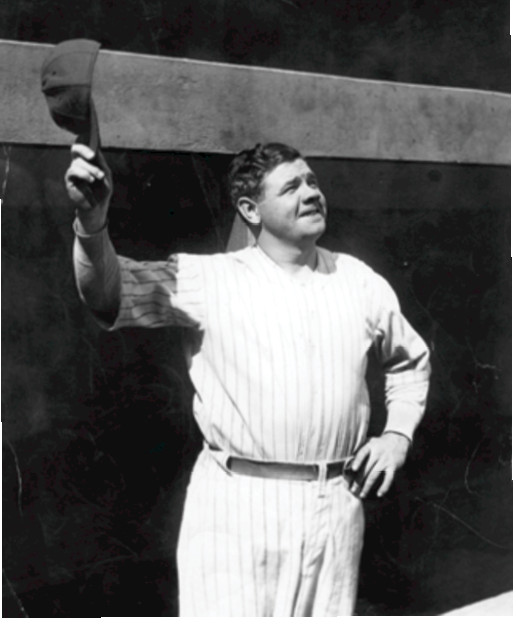

Ever the celebrity, Babe Ruth doffs his cap. (Library of Congress.)

Of any athlete from any sport who does double duty on the big screen and the ballyard/gridiron/basketball court, none has been written about, analyzed, and overanalyzed as much as Babe Ruth. Not Jim Brown. Not Michael Jordan. Not Willie, Mickey, or The Duke.

Upon winning fame as the Sultan of Swat, Babe Ruth often appeared in venues other than ballparks. He was a popular personality in vaudeville, on the radio – and onscreen. So it is no revelation that The Babe would be cast to play himself opposite Gary Cooper’s Lou Gehrig in The Pride of the Yankees (released in 1942), would clown with Harold Lloyd in a taxi headed to Yankee Stadium in Speedy (1928), and would star in features and short films of various types during the 1920s and ’30s.

In 1932 The Bambino toplined a series of one-reel Universal photoplays, labeled the “Babe Ruth Baseball Series,” which included athletic coaching; among its titles are Just Pals, Perfect Control, Fancy Curves, Over the Fence, and Slide, Babe, Slide. He was featured in a range of documentaries and instructional films, from 1920’s Over the Fence, Play Ball With Babe Ruth, and How Babe Ruth Hits a Home Run to 1939’s Touching All Bases.1 However, these titles – with one exception – are bunt singles when compared to the dingers that are The Babe’s feature-length films. That one is a one-reeler: Home Run on the Keys (1937), in which he offers his “official” take on his celebrated called shot off the Chicago Cubs’ Charlie Root in the 1932 World Series.

Home Run on the Keys features The Babe on a hunting trip, and he is shown spending time in a cabin with songwriters Zez Confrey and Byron Gay. Here is his claim:

Well, I’ll tell ya. The papers said it was the longest and the most dramatic home run ever hit at the Cubs park. I’ll never forget it. It was a tough Series. Both clubs riding each other. Doing everything to get each other’s goat. Well, at this one particular time when I went to bat, Charlie Root was pitching, and the first pitched ball was a called strike. Well, I thought it was outside and didn’t like it very much. So the boys over there were given me the ‘on ya’ ‘on ya.’ You know what I mean. … Well, the second pitched ball was another called strike. Well, I didn’t like that one either. So, I let it go by. And by that time, they were over there going crazy! Well, I stepped out of the box and I looked over to the bench and then I looked out at center field and I pointed. I said, ‘I’m going to hit the next pitched ball right past the flag pole.’ Well, the good lord and good luck must have been with me because, I did exactly what I said I was going to do. And I’ll tell you one thing; that was the best home run I ever hit in my life.2

Of course, The Bambino first came to the majors in 1914, but it was not until he arrived in New York in 1920 that his screen career commenced with the production of Headin’ Home, a low-budget comedy-drama presented by Kessel & Baumann and produced by the Yankee Photo Corporation. While Headin’ Home is no classic of its era, its historical worth is obvious if only for The Babe’s presence. His character may be called “Babe,” but there is nothing genuinely biographical here; when the film was produced, his rough upbringing and off-the-field antics were unknown commodities. So depicting Ruth as a humble, stereotypical all-American boy who adores his mother and lives with her and his kid sister in Haverlock, “a little egg and hamlet in the sticks,” was a smart marketing ploy. So is showing Babe chopping wood, which he fashions into the baseball bats he employs to smash heroic dingers. He favors peaceful evenings savoring his mom’s home cooking, and his innate shyness separates him from the girl he secretly adores: Mildred Tobin (played by Ruth Taylor), the town banker’s offspring. During the course of the scenario, Babe belts a game-winning dinger in a local exhibition; saves Mildred from the clenches of a lawbreaker; wins acclaim as a home-run-bashing big-league star; rescues Mildred’s brother from a vamp; and returns to Haverlock, where he homers in front of the locals.

As noted on the Turner Classic Movies website, “Just as Babe Ruth was becoming the ballplayer who epitomized the 1920’s, Headin’ Homewas the one baseball film that embodied the mass-marketing of the sport. No measly movie palace could house it during its New York premiere. Fight promoter Tex Rickard reportedly paid $35,000 to book the film into Madison Square Garden, where it was screened from September 19 to 26, 1920.Variety, the motion-picture trade publication, informed its readers that moviegoers could purchase everything “from Babe Ruth phonographic records to the Babe Ruth song, ‘Oh You Babe Ruth,’ which was sung and played by Lieut. J. Tim Bryan’s Black Devil Band, which accompanied the picture.”3

For decades, Headin’ Home existed only in brief excerpts or “complete” films that were shortened and heavily edited. A visually fuzzy VHS tape could be purchased from Grapevine Video, which markets silent films in the public domain. But then professors-film archivists Ted Larson and Rusty Casselton reconstructed an almost complete 16mm version, with a 73-minute running time. Their print was shown in the mid-1990s at a number of venues, from New York’s Film Forum (in celebration of The Babe’s centennial) to Syracuse’s Cinefest (a now-defunct festival of rare vintage films) and the Louisville Bat Museum (at an annual Society for American Baseball Research convention).

Casselton offered a detailed chronicle of the manner in which the restoration evolved. It serves as a textbook example of the rediscovery and restoration of “lost” films:

In 1993, I received a call from a friend in Arizona about a woman who had a nitrate feature in her front closet. She had inherited the film from her father, and he always told her that it was very special because it starred ‘Baby Ruth.’ The Arizona print had no title and was brittle from age. The film was distributed on a states rights basis, and this print had been edited to remove references to bootlegging and illegal drinking.

Ted (Larson) and I started to talk about preserving the film and at that time Bruce Goldstein at the Film Forum was putting together a program for the Babe’s 100th birthday. He arranged for Collector’s Sportslook, a magazine edited by Tucker Smith, to help fund the event and preservation. Now that some of the finances were in place I got serious about the project. … I ended up tracking down a second nitrate print from a collector in Connecticut. The ‘Connecticut’ print had an original main title and a total of nine other inserts that had been cut out of the ‘Arizona’ print. It was, however, missing the last five minutes, and (there were) gaps throughout in the general continuity.

I (was) aware of yet another source for material on the film. Many years ago, a company released in 16mm a very substantial print of the film. There certainly would be no use for that material except for the fact it had one more scene that was still missing from the composite master. I tracked down the negative for that print, but the owner would not cooperate and make the scene available to be incorporated into the restoration print. The scene is near the end of the film, when Babe goes home to visit his sweetheart. The girl’s father now accepts Babe and they leave the room. At this point the print cuts and what is missing is a scene with Babe and the father in the basement with a still having a good old time. I guess this leaves the current print as a restoration project in progress. Someday, it will be completed.4

If it ever is, neither Casselton nor Larson will be involved as both have since died. However, a different Headin’ Home restoration – this one a 50-minute-long 35mm print – was shown in April 2006 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in a 12-film program titled “Baseball and American Culture.” The New York Times dubbed it “a rare, freshly restored silent”5 and the New York Daily News quoted Carl E. Prince, former chairman of the New York University History Department, who organized the series with Charles Silver, a curator in MoMA’s Department of Film. “(Headin’ Home) hasn’t been seen in over 80 years,” Prince claimed while hyping the program. “It’s about home, mother and apple pie – it’s just wonderful.”6 It was as if the Larson-Casselton restoration, let alone the Grapevine Video edition, never existed.

A year after the MoMA program, Headin’ Home was included in Reel Baseball, a two-DVD set released by Kino International and consisting of two features (Headin’ Home and The Busher) and 11 shorts released between 1899 and 1926. The version here is the 73-minute Larson-Casselton print.

The Bambino’s other silent feature, Babe Comes Home, dates from 1927. During its extensive publicity campaign, the film was erroneously hyped as Ruth’s screen debut: “On July 1,” noted the New York Times, “Babe Ruth’s first picture, ‘Babe Comes Home,’ is to be offered at the Longacre Theatre.”7 But unlike Headin’ Home, Babe Comes Home is long-lost. Countless silent films have for one reason or another faded into the mists of history; as each year passes, chances are slim to none that Babe Comes Home will reappear after being hidden in the vault of a film archive or in a film collector’s attic. However, 13 seconds worth of Babe Comes Home-related visuals may be seen on YouTube. Here, The Babe is ever-so-briefly shown having makeup applied and carousing on the set.8

Babe Comes Home mirrors the by-then-established view of The Babe as a reveler. Plus, it certainly is of its time as a proud proponent of tobacco usage. In The American Film Institute Catalog of Feature Films 1921-30, Babe Comes Home is described as a comedy in which Ruth plays “Babe Dugan, star player with the (Los Angeles Angels) baseball team. He chews tobacco and gets his uniform dirtier than any other player. Vernie (played by Anna Q. Nilsson), the laundress who cleans his uniform every week, becomes concerned over his untidiness. Babe calls to apologize for unintentionally striking her with a ball during a game. … On an outing to an amusement park, a roller coaster throws Vernie into Babe’s arms; soon they are engaged, and Vernie plans to reform him. Scores of tobacco cubes and spittoons are pre-wedding gifts. And they precipitate a lovers’ quarrel. But Babe takes the reform idea seriously, though his game slumps and he is put on the bench. At a crucial moment, Vernie relents and throws him a plug of tobacco; and consequently he delivers a four-base blow.”9

Cinematically speaking, neither Headin’ Home nor Babe Comes Home would have earned Academy Award nominations (if in fact the Oscars existed at the time of their releases) or landed on critics’ 10 Best Films lists. The essence of Headin’ Home was summed up by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle: “Were it not for the fact that Ruth is the star, the film would attract very little attention. … If you are interested in the ball player, there are enough good scenes of the home run hitter in the film to make the picture satisfactory.”10 Babe Comes Home, meanwhile, earned mixed reviews. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle described it as “not a very good picture,” adding, However, (Ruth declared that) he had just loads of fun making it. … Anyway, Babe Ruth is a very, very fine ball player.”11 The New York Times labeled it a “broad comedy, and commented, “It’s rough-house stuff, but full of fun. … Mr. Ruth himself makes a pleasing screen figure. …”12

Added Harold Heffernan, writing about Babe Comes Home in the Detroit News:

Babe Ruth has arrived on the screen … but there is no particular reason for John Barrymore or any of the other noted film thespians to become agitated about the matter. Mr. Ruth is a solid, healthy appearing actor, not especially attractive in comparison to some of our male idols, but probably much better than you ever hoped for. Possibly his long experience with the newsreel cameramen is responsible for his ability to keep his eyes out of the camera lens – something few movie beginners are able to do.

The Bambino, Sultan of Swat, Home Run King or whatever you wish, is the whole show, plus the box office, in ‘Babe Comes Home.’ Everything is built around him, over him and under him. The story is rather slim and is liberally padded, but for this type of picture is much better than the average. … There is a big game for the pennant (at the finale). Babe is in a slump because he has sworn off tobacco chewing. (During) the ninth inning crisis, the girl leans over the box into the playing field and hands Babe a plug of the old stuff, and bang goes the ballgame!13

The Babe went on to act in two major Hollywood features, both of which differ from Headin’ Home and Babe Comes Home in that he is not the star. Certified screen legends are the headliners – and in both, The Bambino appears in support as himself.

The first is a silent comedy: Speedy, starring Harold Lloyd and released in 1928. Here, Lloyd – who joined Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton as the premier silent screen clowns – plays Harold “Speedy” Swift, a baseball fan-atic of the first order. Jane Dillon (Ann Christy), his girlfriend, declares that her guy “gets plenty of jobs – but he’ll never keep one while his mind is full of baseball.” His latest gig is as a cabbie, and he reads in a newspaper that The Bambino will momentarily be autographing baseballs to kids at the City Orphan Asylum. It so happens that Speedy is parked nearby and is determined to gaze at his hero, who is besieged by overzealous fans. Upon realizing that he must head off to his workplace, The Babe hails Speedy’s taxi.

The overly-excited cabbie gives The Babe a comedy-laden ride: “Gosh, Babe – this is the proudest moment of my life,” he declares while veering through traffic and coming perilously close to other autos and pedestrians. “If I ever want to commit suicide I’ll call you,” the ballplayer informs the driver. However, The Babe’s presence does not end upon arriving at Yankee Stadium, as he invites Speedy into the ballyard to watch the contest. Speedy is overwhelmed with elation as The Bambino homers. He whacks the pate of the fan in front of him, who just so happens to be his new employer. So Speedy’s career as a cabbie ends before it begins.

Much can be said about The Pride of the Yankees. As it charts the evolving relationship between Lou Gehrig and his beloved Eleanor (Teresa Wright), it is as much a love story as a baseball film. Its content is unabashedly patriotic, and it came to movie houses in July 1942, seven months after Pearl Harbor; Damon Runyon penned the film’s preface, in which he labels it “the story of a gentle young man who … faced death with the same valor and fortitude that has been displayed by thousands of young Americans on far-flung fields of battle. …”14

The Bambino plus Mark Koenig, Bob Meusel, and Bill Dickey play themselves in The Pride of the Yankees. And here he is presented as very much the stereotypical, beloved Babe who favors locker-room clowning as much as on-field heroics. Still, the film’s center is Larrupin’ Lou. If The Sultan of Swat assures a bedridden boy that he will homer in the World Series, which he does, Gehrig is swayed into forecasting that he will belt two long balls – which he does. Unsurprisingly, the long-standing feud between the two Yankees is nonexistent; however, it is symbolically represented via the repartee between a sportswriter (played by Walter Brennan) and a sarcastic colleague (Dan Duryea).

Typical reviews for Speedy and The Pride of the Yankees cite The Bambino’s presence. Wrote Mordaunt Hall, reviewing Speedy in the New York Times, “The big Babe does some excellent acting, for if ever a man looked nervous as the vehicle in which he was riding shaved by other cars, it is the illustrious King of Swat.” 15 As for Pride …, Time magazine noted that “Babe Ruth is there, playing himself with fidelity and considerable humor. …”16

For indeed, The Bambino was a natural in front of the cameras and might have savored a lengthy career onscreen. But he was not going to embrace Shakespeare, Eugene O’Neill, or George Bernard Shaw. The Three Stooges were more his style and he could have been transformed into Stooge Number Four, with Moe, Larry, and Curly hooking up with The Babe to merrily toss pies in one another’s faces.

ROB EDELMAN (1949-2019) was the preeminent expert on the history of baseball in film and cinema, publishing countless articles and several books on that subject. He was the editor of SABR’s From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors in 2018, and also wrote Great Baseball Films and Baseball on the Web.

Notes

1 imdb.com/name/nm0751899/?ref_=nv_sr_1.

2 imdb.com/title/tt0144970/quotes?ref_=tt_ql_trv_4.

3 Rob Edelman, “Silent Baseball Part 1,” tcm.com/this-month/article.html?id=180852%7C180854.

4 Casselton’s comments first appeared in the SABR 27 Convention Program, which took place in Louisville June 20-23, 1997. Sections were reprinted first in Volume 5, Number 2 of Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game (Fall 2011) and then online in John Thorn’s Our Game. (ourgame.mlblogs.com/lost-and-found-baseball-part-2-12163c87037b).

5 Terrence Rafferty, “Baseball on the Screen: Some Hits, Many Errors,” New York Times, April 2, 2006.

6 Julian Kesner, “Bases Loaded: A festival of Baseball Films Steals Home in Time for the Season,” New York Daily News, April 2, 2006.

7 “Brains and Blondes,” New York Times. June 26, 1927.

8 youtube.com/watch?v=pSdccXob6bk.

9 The American Film Institute Catalogue, Feature Films 1921-30 (New York and London: R.R. Bowker Company, 1971).

10 “Ruth’s Film Show,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 20, 1920.

11 Martin Dickstein, “New Films – and Vocafilms,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 26, 1927.

12 “The Screen,” New York Times, July 26, 1927.

13 Harold Heffernan, “Babe Comes Home: Babe Ruth, Good Ballplayer,” Detroit News. May 16, 1927.

14 reelclassics.com/Movies/Yankees/yankees.htm.

15 Mordaunt Hall, “The Screen,” New York Times, April 7, 1928.

16 “The New Pictures,” Time, August 3, 1942.