Was Willie Keeler the First to Record Four 5-Hit Games in a Season During the 19th Century?

This article was written by Brian Marshall

This article was published in Spring 2018 Baseball Research Journal

The feat of collecting five or more hits in a single game was rare enough, even for baseball in the nineteenth century, but when one player managed to do it in four separate games during a single season, that was one of the rarest accomplishments in the history of baseball. In fact, it was so rare that it was only accomplished once: According to at least three record books, Willie Keeler had four five-hit games in 1897.The feat of collecting five or more hits in a single game was rare enough, even for baseball in the nineteenth century, but when one player managed to do it in four separate games during a single season, that was one of the rarest accomplishments in the history of baseball. In fact, it was so rare that it was only accomplished once: According to at least three record books, Willie Keeler had four five-hit games in 1897.1

This piece will provide a short discussion of career five-hit games, introduce the names of two other players who should be included on the list, and bring the reader’s attention to a discrepancy that exists regarding Keeler’s season totals for at-bats and hits.

Willie Keeler 5-Hit Game Analysis

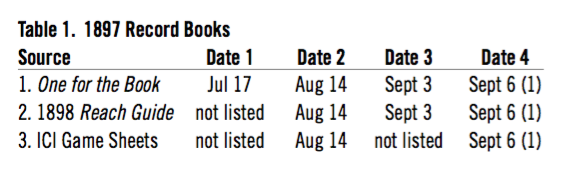

Keeler’s 1897 season included a 44-game hit streak that began with the first game of the season.2 While most record books credit him that year as the only player to get five or more hits in a game four times, the 1898 Reach Guide only credited him with three such games on page 35, devoted to “Individual Batting Feats.”3 Meanwhile, the Information Concepts Incorporated (ICI) game-by-game spreadsheets for Willie Keeler in 1897 only showed two five-hit games.4 The plot thickens. See Table 1.

Keeler’s 1897 season included a 44-game hit streak that began with the first game of the season.2 While most record books credit him that year as the only player to get five or more hits in a game four times, the 1898 Reach Guide only credited him with three such games on page 35, devoted to “Individual Batting Feats.”3 Meanwhile, the Information Concepts Incorporated (ICI) game-by-game spreadsheets for Willie Keeler in 1897 only showed two five-hit games.4 The plot thickens. See Table 1.

Which was it: two, three, or four? The fact that three separate, credible sources had different answers is something of a head-scratcher. I consulted my own files, which included electronic copies of various newspapers as well as box scores—created by me—for every game played by Keeler’s Baltimore Orioles in 1897.

The four five-hit games that “Little Willie,” as he was called by the Sporting Life, was credited with by multiple sources were as follows: July 17 at Chicago Colts, August 14 at Philadelphia Phillies, September 3 vs. St. Louis Browns, and the first game of a doubleheader September 6 vs. Pittsburgh Pirates.5 In order to research the claim of these four five-hit games, I looked at the 1898 Reach Guide and the ICI game-by-game data sheets for Keeler in 1897, as well as the following publications:

- Three Baltimore newspapers: the American, Sun, and Herald.

- At least one newspaper from the city of the opposing team.

- The Sporting News, Sporting Life, and New York Clipper.

- Miscellaneous newspapers as detailed below.

The Baltimore American, Baltimore Sun, and Baltimore Herald all included box scores in their game coverage, while the Baltimore World only provided minimal coverage that typically did not include a box score.

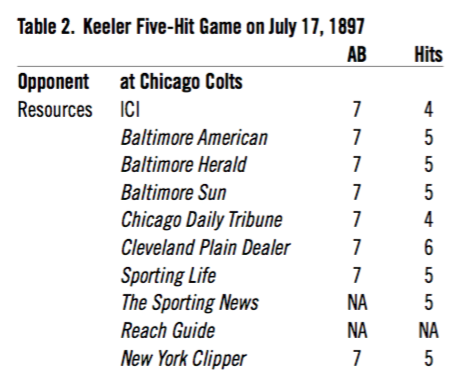

The information for the first game, July 17 at Chicago, is presented in Table 2.

The data, where available, are listed for each of the resources. In this case, nine of the 10 resources contained at least hits data. The majority of sources credited Keeler with five or more hits, though two sources—the Chicago Daily Tribune, from the home team’s city, and ICI—indicate that he had only four.6 The box score in the Tribune showed that Keeler reached base on an error. According to the Baltimore Herald: “Corbett opened the fifth with a bunt, McGraw hit safely. Keeler bunted to third and Everitt threw wild to first, Corbett and McGraw scoring and Keeler going to third.”7

This is exactly the sort of hit Keeler was known for. The play was scored as an error by a Chicago scorer and a hit by the Baltimore scorer, hence the discrepancy in the box scores. According to the scoring rules, the play should have been scored as a hit.8 Everitt appears to have been hurried in his effort to field the ball and air-mailed the throw. We can’t know if Everitt might have been able to throw Keeler out if he hadn’t thrown wild to first, nor if it should have been scored a hit, but at the time, Keeler was well established as a “scientific hitter,” and it was well within his skill set to beat out a bunt.9 As further validation of July 17 as a five-hit game for Keeler, a short article, dated August 9, in the August 21 issue of Sporting Life listed the players with five or more hits in a game to that point and Keeler was credited with one such performance.10

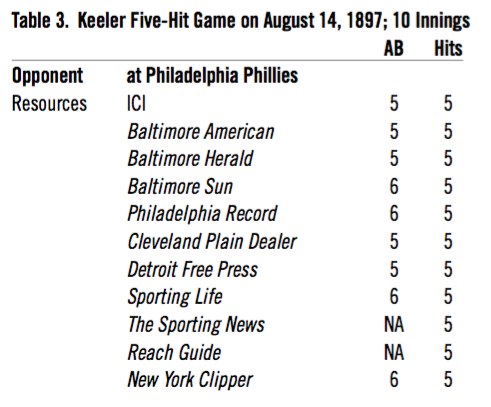

The information for Keeler’s second five-hit game, an extra-inning game on August 14, 1897, is presented in Table 3.

Table 3 indicates that each of the sources credited Keeler with five hits, although there is disagreement about how many at-bats he had. Four sources, one of them the Baltimore Sun, show Keeler with six at-bats rather than five.11 It wasn’t uncommon for box scores in different newspapers to vary in this way. All sources agree that Keeler had five hits, but it is interesting that the at-bats vary since there isn’t any indication Keeler had a sacrifice hit, walked, or was hit by a pitch. According to the box score, though, he must have batted six times because Hughie Jennings, who batted second, after Keeler, had four at-bats as well as two sacrifice hits for a total of six plate appearances, and Joe Kelley, who batted third, had five at-bats and one sacrifice hit. Keeler must have had six plate appearances, and may have had six at-bats.

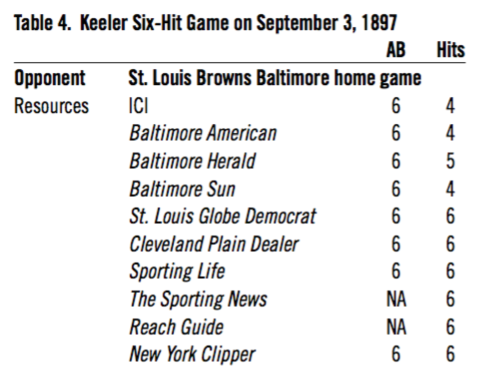

Keeler’s third game with five or more hits, on September 3, 1897, is represented in Table 4.

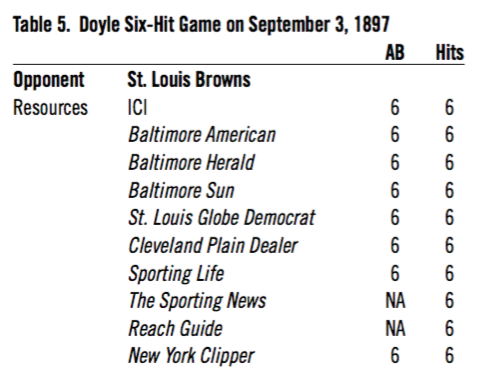

Again, the resources have conflicting information, with Keeler’s hit total ranging from four to six, though seven of the 10 have him with at least five. The at-bat total is consistent where it’s provided. Keeler wasn’t the only Oriole to collect six hits on September 3. His teammate Jack Doyle did it too, as shown in Table 5.

The consistency of the Doyle data compared with the inconsistency of the Keeler data may have stemmed from the difference in the two players’ hitting techniques. Keeler’s hits were often of the type that forced the fielder to hurry the process of both fielding and throwing. That increased the likelihood the play would be muffed. The scorer was then forced to decide between scoring the play as a hit or an error. As with the July 17 game, there was mention in the Baltimore Sun that Keeler may have reached first base because of a “fumble” by an infielder:

Reitz opened the second inning with a hit, and, with Robinson, played the run-and-hit neatly. Corbett forced Robinson but Reitz scored. McGraw doubled. Cross’ fumble of Keeler’s grounder allowed Corbett to score. Jennings’ grounder also went through Cross and McGraw scored. Kelley’s double scored Keeler and Jennings, who had just previously made a double steal. Stenzel flied to Harley, but Kelley scored on Doyle’s hit. Reitz flied to Turner.12

It’s odd that two of the Baltimore newspapers and the ICI folks credited Keeler with only four hits, considering that at least two publications at the time credited him with six and that virtually every list of six-hit performances published in later years includes Keeler’s September 3 game.13 And that’s not to mention Keeler and Doyle commonly credited as being the only two players to have six hits in the same game, teammates or not.14

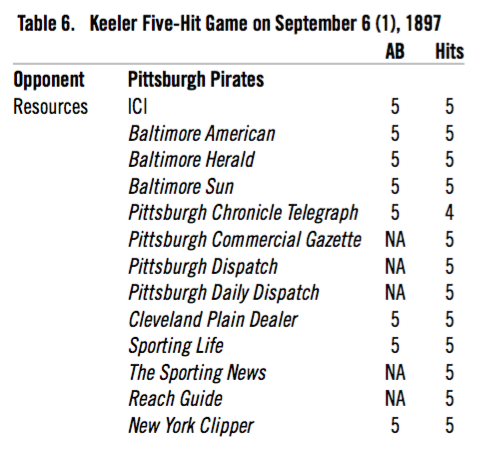

The last of the four games was the first game of a doubleheader played on September 6, 1897. The information is in Table 6.

It is clear to see that all of the references except one indicated that Keeler had five hits and that all references that listed at-bats credited him with five. The Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph was the only source that showed Keeler with four hits rather than five, and as the reader may guess, it had to do with the assignment of an error for one of Keeler’s hits. The date for this game, September 6, is incorrectly listed as September 5 on page 35 of the 1898 Reach Guide. The Baltimore Orioles did not play a game on September 5.

The Official Batting Averages for 1897

At the end of the 1897 season, not everyone was in agreement with Keeler’s “fat” batting average, as it was referred to in a Sporting Life article that also alluded to a scoring bias:

Frank Houseman, of St. Louis, is home for the winter. Frank has little to say about the Browns, but has much ridicule for the other teams, and wild kicks against the fat average of Billy Keeler. “In Baltimore one day,” says Frank, “I saw Keeler hoist two flies to left, and Dan Lally muffed them both. Then he hit one to third, and Hartman, after fumbling, threw wild to first. Then he made one good single. Next morning—four hits in the Baltimore papers. Oh, they don’t do a thing for their hitters down there.”15

An article in Sporting Life discussed the accuracy of batting averages and mentioned the work of league executive N.E. Young and his son Robert:

There is little chance for error to creep into official figures after they reach headquarters. Mr. Young and son, Robert, are expert accountants, and as one proves the other’s work mistakes are rare indeed.16

A Baltimore American article also mentioned the Youngs:

President Young’s son, Robert, is in the midst of the hardest task that his position imposes—figuring up the averages of the major league players.17

The Sporting News had the following to say about Keeler’s 1897 batting statistics:

The official league base ball figures, compiled by Secretary N. E. Young, give the fine young batsmen of the Baltimore Club, William H. Keeler, a higher batting percentage than was accorded him by unofficial competants [sic]. He batted .432 this past season, which means that he made 43 hits for every 100 times at bat. This is batting a little better than two hits every five times at bat, a very fine performance.18

It would be interesting to see the game-by-game numbers Young’s son, Robert, had in front of him when he compiled the “official” batting average for Willie Keeler in 1897.

My research has identified at least one other NL player who had at least five hits in a game four times in a season during the nineteenth century. Sam Thompson of the Detroit Wolverines did it in 1887, predating Keeler’s performance by 10 years. Thompson had five or more hits on May 16 at the Philadelphia Quakers; June 10 vs. the Indianapolis Hoosiers; July 25 vs. the Chicago White Stockings; and September 23 vs. the New York Giants. In addition, he may have done it on August 9 against the Washington Nationals at home, but the Washington Post and New York Clipper both credited him with only four hits.19

One more name should be added to the list of those who accomplished the feat: Tip O’Neill of the St. Louis Browns. O’Neill’s performance also occurred in 1887, although it was in the American Association. His games with five or more hits were: April 30 vs. Cleveland; August 24 vs. the Baltimore Orioles; September 2 at the Metropolitans; and September 7 at Brooklyn. Since both the Thompson and O’Neill performances were in 1887, when bases on balls were typically included in the hit column, I only considered “actual” hits in each case. Those can be found in the New York Clipper box scores because the Clipper, unlike most other publications, didn’t go along with counting bases on balls as hits.20

Conclusions

The data presented in this analysis lean heavily in support of the proposition that Willie Keeler did have four games during the 1897 season in which he had five or more hits. The majority, and in one case all, of the contemporary sources for each of the four games supports Keeler’s achievement being genuine, as do several record books.

My analysis identified scoring discrepancies in both at-bats and hits, and I suspect that given the primitive nature of fielding at the time, many of the plays could have been scored as errors. I also suspect that while many scorers interpreted the rules properly, home-team bias existed. It would be interesting to have some insight into the thought process that went into ICI’s compilation of its game-by-game batting data for Keeler in 1897. I’m quite sure, given the box-score discrepancies, that the ICI folks also had to make decisions about which data they believed were the most correct. Unfortunately, ICI did not provide notes that detailed its process of data qualification or listed the resources it used.

We can see how ICI was prone to errors if we consider the home run it credited to Keeler for the July 11, 1897, game against the St. Louis Browns.21 I’ve reviewed game accounts and box scores from many sources for that game and have yet to see one that credits Keeler with a home run. The game was played in St. Louis and there was a Baltimore home run, but it was hit by Jake Stenzel, not Keeler. Stenzel also hit a triple in the game. Many Eastern newspapers of the time, including those in Baltimore, the Sporting Life, and the New York Clipper, did a strange thing: They didn’t list “three base hits” below the box score, only “two base hits” and “home runs.” Interestingly the newspapers for Western teams did list “three base hits.” Stenzel went 4-for-5 and hit for the cycle in that July 11 game, but it might have been missed depending on the newspaper a person had access to. ICI correctly credited Stenzel with hitting for the cycle on July 11, 1897, which shows that the source(s) the ICI folks were using included “three base hits.”

Research into Keeler’s performance has also identified two other names, Sam Thompson and Tip O’Neill, that should be added to the list of those who managed to have five or more hits in a game four times in one season.

General Notes About Five-Hit Game Performances

The research for this analysis also identified an error in the number of career five-hit games credited to an individual. The 2016 Elias Book of Baseball Records indicates that Ty Cobb holds the lifetime record with 14 such games. My research indicates that Cap Anson had at least 16 games in his NL career with five or more hits. I have documented, to date, over 2,000 discrete four-plus-hit performances by an individual in the NL during the nineteenth century. The list, a living document that is constantly changing as new information is uncovered, includes nearly 400 five-hit performances. Anson had at least 50 games with exactly four hits to go along with his 16 five-hit games, for a total of at least 66 career games with four hits or more.22

Prior to the writing of this article, the general thinking, per the information contained in the record books identified in this article, was that Keeler in the NL and Cobb in the AL were the first two players to have five hits in a single game on four separate occasions during a single season. We now know there were at least two other players, one in the NL and one in the AA, who had four five-hit games 10 years prior to Keeler’s performance. (A comparison of the five-hit games of Sam Thompson, Tip O’Neill, Willie Keeler, and Ty Cobb may be found in Appendix 1 below.)

The research for this article is an excellent example of the data discrepancies a researcher encounters when studying nineteenth-century baseball. The researcher has to be wary of conflicting information, and a box score should not be considered gospel unless it is the only box score that exists for a given game. Quite often, once multiple sources have been reviewed, some interpretation is required in order to better identify the correct data. The more game accounts, box scores, game notes, and data researchers have at their fingertips the better, but it can still be a bit of a crapshoot. It is for these very reasons that researching nineteenth-century baseball can be challenging, but also rewarding.

BRIAN MARSHALL is an Electrical Engineering Technologist living in Barrie, Ontario, Canada and a longtime researcher in various fields including entomology, power electronic engineering, NFL, Canadian Football and MLB. Brian has written many articles, winning awards for two of them, and has two baseball books on the way: one on the 1927 New York Yankees and the other on the 1897 Baltimore Orioles. Brian has become a frequent contributor to the “Baseball Research Journal” and is a longtime member of the PFRA. Growing up, Brian played many sports including football, rugby, hockey, and baseball, along with participating in power lifting and arm wrestling events, and aspired to be a professional football player, but when that didn’t materialize he focused on Rugby Union and played off and on for 17 seasons in the “front row.”

Appendix 1

Author’s note

The author presented some of this material at the SABR Frederick Ivor-Campbell 19th Century Baseball Conference at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown on April 17, 2015.

Notes

1 Leonard Gettelson, One for the Book: All-Time Baseball Records (St. Louis: Charles C. Spink & Son, 1963); Seymour Siwoff, ed., The Book of Baseball Records (New York: Seymour Siwoff, 1982); Siwoff, ed., The Elias Book of Baseball Records (New YorkSeymour Siwoff, 2016). In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the feat has been accomplished by Ty Cobb in 1922, Stan Musial in 1948, Tony Gwynn in 1993, and Ichiro Suzuki in 2004.

2 Keeler had a hit in the last game of the 1896 season, so his hit streak can be considered to be 45 games.

3 A.J. Reach, Reach’s Official Base Ball Guide for 1898 (Philadelphia: A. J. Reach, 1898, reprinted by Horton Publishing, 1990).

4 The Baseball Encyclopedia: The Complete and Official Record of Major League Baseball (New York: Macmillan, 1969). David Neft was the man behind ICI. Its research and data formed the basis for the Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia of 1969.

5 “Little Willie: Some Facts About a Great Ballplayer,” Sporting Life, July 3, 1897.

6 “Champions Slaughter the Colts,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 18, 1897.

7 “Champs Hit For Keeps,” Baltimore Herald, Sunday, July 18, 1897.

8 Reach, Reach’s Official Base Ball Guide for 1897. Rule 71: Scoring, Section 3 (under Batting) reads that a base hit should be scored “when a hit ball is hit so sharply to an Infielder hat he cannot handle it in time to put out the Batsman” or “when a hit ball is hit so slowly toward a Fielder that he cannot handle it in time put out the Batsman.”

9 “Little Willie.”

10 “Anson’s Five Hits,” Sporting Life, August 21, 1897.

11 “Won From Philadelphia,” Baltimore Sun, August 16, 1897.

12 “Browns Overwhelmed,” Baltimore Sun, September 4, 1897.

13 George L. Moreland, Balldom: The Britannica of Baseball, Fascinating Facts For Fans, Fourth Ed. (Youngstown, OH: Balldom Company, 1927), 161; John B. Foster, ed., The Little Red Book: Spalding’s Official Base Ball Record, (New York: American Sports Publishing, 1928), 70; Gettelson, One for the Book (1963); “Batting Feats: A Few of the Records Made During the 1897 Campaign,” Sporting Life, December 25, 1897.

14 Reach, Reach’s Official Base Ball Guide for 1898; Moreland, Balldom.

15 “Odds and Ends,” Sporting Life, October 23, 1897.

16 “Comment on the League’s Official Batting Averages,” Sporting Life, October 23, 1897.

17 “Gossip of the Diamond,” Baltimore American, October 10, 1897.

18 “Model Player: Is Keeler the League’s Best Batter?” The Sporting News, October 30, 1897.

19 “Lost By Poor Fielding,” Washington Post, August 10, 1887; “Baseball: National League: Detroit vs Washington,” New York Clipper, August 20.

20 “Short Stops,” New York Clipper, April 30, 1887.

21 With the ICI data representing the basis for the Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia, the incorrect Keeler home run datum was replicated there, but Total Baseball, for example, corrected the error. John Thorn & Pete Palmer, eds., Total Baseball (New York: Warner Books, 1989).

22 I use the phrase “at least” because I noted the performances as I came across them, but I wasn’t specifically researching the literature for them, and as a result may