Arizona Diamondbacks team ownership history

This article was written by Clayton Trutor

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

In the 21 years since Major League Baseball granted an expansion bid to Arizona Baseball, Inc., the Arizona Diamondbacks franchise has been characterized by the stability of its leadership. The franchise has had two managing general partners, the term it uses for its chief executive officer: Jerry Colangelo (1995-2004) and Ken Kendrick (2004-). The actual ownership of the club has been far more divided. Dozens of investors backed Phoenix Suns executive Jerry Colangelo’s original ownership group, Arizona Baseball, Inc., in 1995. Ken Kendrick leads a four-man ownership group that also includes Jeffrey Royer, Michael Chipman, and Dale Jensen, all of whom have owned at least a portion of the club since its inception.

In contrast, the Diamondbacks’ on-the-field performance has been consistently inconsistent ever since those heady early years. The team was a near-immediate contender for a world championship. Despite the Diamondbacks’ more recent struggles in the standings, the steadiness of its leadership transformed the franchise into one of the National League’s most respected almost immediately.

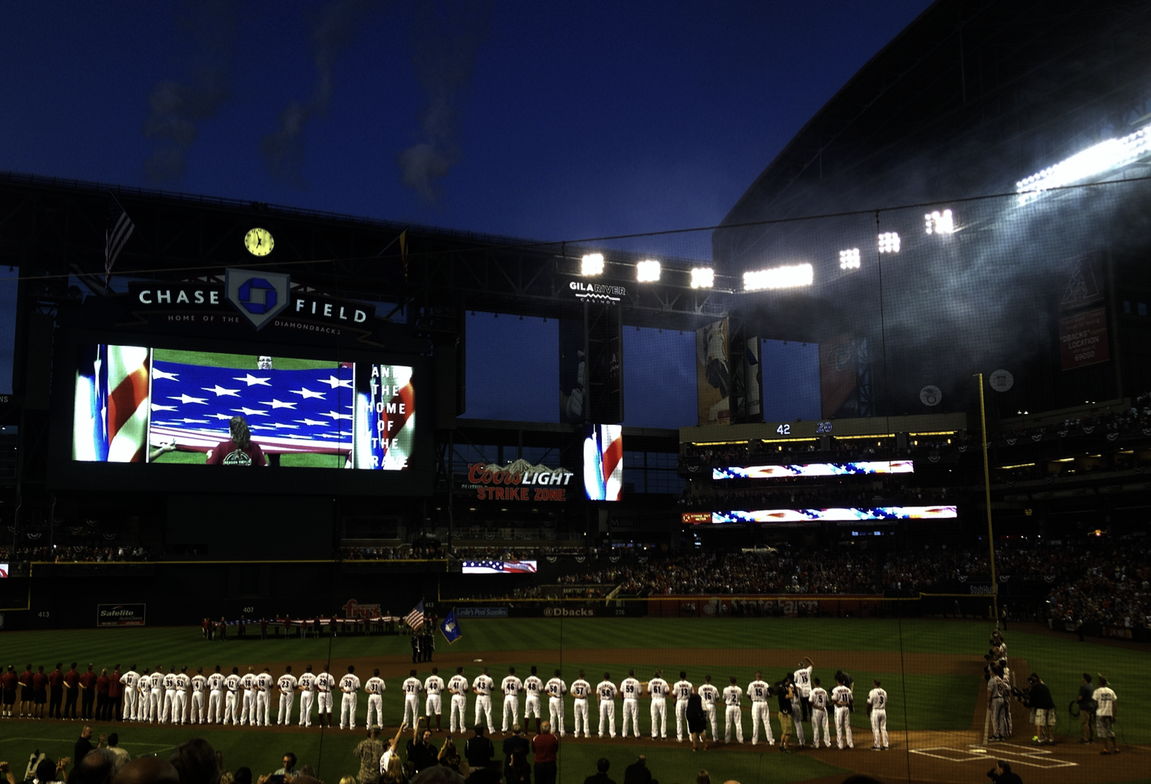

The National Anthem is played before the Arizona Diamondbacks game on April 6, 2015, at Chase Field in Phoenix, Arizona.

Metropolitan Phoenix’s Path to the Major Leagues

The arrival of major-league baseball in metropolitan Phoenix in 1998 was preceded by a half-century of close ties between the Valley of the Sun, as Phoenix and 9,200-square-mile Maricopa County are widely known, and the big leagues. The Arizona State University baseball program has been a national collegiate power since the mid-1960s. As of 2016 the Sun Devils have won five NCAA championships, appeared in 22 College World Series, and produced numerous major-league stars, including Reggie Jackson, Bobby Bonds, Dustin Pedroia, and Bob Horner. Since 1992, metropolitan Phoenix has hosted the six-team Arizona Fall League, which provides outstanding minor-league prospects with the opportunity to play in a highly competitive atmosphere once their Double-A and Triple-A seasons have concluded.

Metropolitan Phoenix’s most significant historical connection to the majors has been as the primary host of the Cactus League. Arizona has been home to major-league spring training since the immediate aftermath of World War II. In 1947, the Cleveland Indians began taking up preseason residence 120 miles southeast of Phoenix in Tucson, the winter home of the club’s new owner, Bill Veeck. Veeck persuaded New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham to join the Indians in Arizona. Stoneham placed his club’s spring-training camp in Phoenix. In 1952 the Chicago Cubs, who had previously trained on owner Phil Wrigley’s Catalina Island (California) estate, began training in Mesa, just to the east of Phoenix. The arrival of the Cubs and the off-and-on presence of other clubs helped to formalize the existence of the Cactus League, the Grand Canyon State’s spring-training counterpart to Florida’s Grapefruit League.1

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the Cactus League remained a small yet stable operation, growing slowly to an eight-team league as Major League Baseball expanded rapidly from 16 to 26 teams. Several of the Midwestern clubs in the Cactus League, particularly the Cubs, turned their spring-training homes into popular winter tourist destinations for their fan bases as well as homes away from home for seasonal residents or permanent transplants to Arizona.2

In 1989 the eight-team Cactus League was in danger of losing one of its founding members.

The Cleveland Indians announced plans to move their spring-training headquarters from Tucson to Homestead, Florida. The impending departure, which threatened the existence of the Cactus League, provoked immediate action from local political leaders, including US Senator John McCain, Governor Rose Mofford, and Maricopa County Supervisor Jim Bruner, who later played a major role in the arrival of the Diamondbacks in Arizona. In 1990 the Arizona Legislature passed legislation that created a Maricopa County stadium district governed by the county Board of Supervisors. The measure authorized the county to collect a $2.50 car-rental tax. The revenue from the tax helped revitalize existing spring-training facilities and build several new complexes, including one for the Indians, who chose to stay in Arizona, moving to the Phoenix suburb of Goodyear in 1993. Four of the publicly financed facilities created by the legislation are each shared by two major-league clubs, including the Indians’ facility in Goodyear, which they share with the Cincinnati Reds. Arizona’s significant public investment in spring-training baseball helped lure a number of franchises to the Cactus League. As of 2016, 15 of the 30 major-league teams belonged to the geographically compact (every team but one is in Maricopa County) and virtually rainout-free Cactus League.3

The Maricopa County Stadium Authority, which was created to save the Cactus League, played a similarly decisive role several years later in the arrival of the Diamondbacks by providing the region with a public institution capable of financing a ballpark costing several hundred million dollars.

Making Phoenix Major league (1985-95)

The first concerted civic effort to secure a major-league franchise began as metropolitan Phoenix, with almost 2 million residents, became the nation’s 14th largest metropolitan area in the late 1980s. Martin Stone, the owner of the Phoenix Firebirds, the San Francisco Giants Triple-A affiliate, was the driving force behind the push. Beginning in the mid-1980s, he sought either an expansion team or a relocated franchise.

The first concerted civic effort to secure a major-league franchise began as metropolitan Phoenix, with almost 2 million residents, became the nation’s 14th largest metropolitan area in the late 1980s. Martin Stone, the owner of the Phoenix Firebirds, the San Francisco Giants Triple-A affiliate, was the driving force behind the push. Beginning in the mid-1980s, he sought either an expansion team or a relocated franchise.

It was no secret that Bill Bidwill, owner of the NFL’s St. Louis Cardinals, intended to move to Phoenix. Stone persuaded Bidwill to join him in building a stadium in the downtown area.

In April 1987 the city agreed to secure $150 million in bonding to build a 70,000-seat domed stadium on a 66-acre parcel of land in the southern section of downtown Phoenix. The stadium was to serve as the springboard to a $500 million downtown redevelopment plan that would include public and private investments in commercial and retail space, hotels, and housing. To pay off the construction bonds, Stone or any other prospective tenant agreed to turn over to the city the proceeds from the sale of 212 luxury skyboxes and 10,800 club seats. All of these plans would be executed once a major professional sports franchise signed a lease to play in the stadium.4

In January 1988 Bidwill won approval from the NFL to move his franchise to Arizona. But instead of becoming a tenant of Stone and the city in the planned domed stadium, Bidwill signed a long-term lease with Arizona State University to play the Cardinals’ games at the football-only Sun Devil Stadium in Tempe, just east of Phoenix. That brought Stone’s plans for a domed stadium to an end. In May 1988 Stone backed out of his deal with Phoenix, arguing that he could no longer negotiate the terms of a stadium lease from a position of strength as he had neither a franchise in hand nor another tenant with whom to share the burden of selling premium seats to the public.5

Without Stone’s backing for the deal, stadium plans languished. In October 1989, nearly 60 percent of Phoenix voters rejected a ballot initiative that would have allowed the issuance of $100 million of the previously authorized bonds for a domed ballpark. Big-league insiders had made it clear to Arizona leaders that public support for a stadium was a prerequisite for serious consideration for a franchise. After the initiative failed, the Legislature passed a law allowing the city to bypass a referendum in their push for big-league baseball. The Legislature also authorized the county Board of Supervisors to impose a 0.25 percent sales tax to help finance construction of a baseball stadium if one of the county’s municipalities was awarded a franchise.6

Stone continued to pursue a major-league team for Phoenix into the early 1990s. Then in 1991, he abandoned his Arizona plans to become a partner in what turned out to be an unsuccessful effort to purchase the Montreal Expos. (There was little indication that Stone pursued a stake in the Expos to move the franchise. Montreal was less than a two-hour drive from his home in Lake Placid, New York.) Stone’s decision to withdraw his Arizona bid brought a de-facto end to Phoenix’s chances to get a team during that expansion cycle, when franchises were awarded to Denver and Miami.7

While Martin Stone spent a half-decade in single-minded pursuit of big-league baseball for the Phoenix area, the bid that actually brought a major-league team to Arizona came together more serendipitously. In early 1993, Maricopa County Supervisor and longtime baseball supporter Jim Bruner began discussing the idea of putting together a bid for a forthcoming new round of expansion with a friend, Phoenix sports attorney Joe Garagiola Jr., the son of the baseball personality, player, and commentator. Later in 1993, Bruner and Garagiola set up a meeting with Phoenix Suns owner Jerry Colangelo, one of the region’s most popular public figures and fervent boosters, to discuss their idea.

Colangelo’s Suns had engendered unprecedented enthusiasm in the region for professional sports with an exciting run to the NBA playoff finals that year. Bruner and Garagiola persuaded Colangelo to spearhead the effort to bring in a baseball team. Taking on this role required Colangelo to manage a $125 million fundraising drive to pay the anticipated franchise fee for the 1994 expansion. Moreover, Colangelo took on the responsibility of negotiating a public financing deal for a downtown baseball stadium.

Several years earlier, the Suns owner had experienced this process while seeking public funds in support of a new venue for the Suns. Colangelo later said that taking the lead in the baseball expansion effort fulfilled his desire to play a more prominent role in increasing the national profile of the Valley of the Sun. He was also playing a central role in negotiating the deal that led to the relocation of the National Hockey League’s Winnipeg Jets to Phoenix’s America West Arena, where they were rechristened the Phoenix Coyotes in 1996.8

Colangelo’s rags-to-riches story was well known to Arizonans with even a passing knowledge of professional sports. Born the son of Italian immigrants in a hardscrabble section of Chicago Heights, Illinois, Colangelo Colangelo made use of his athletic and intellectual abilities as well as his unparalleled work ethic to become a great success. A high-school basketball star, Colangelo gained an athletic scholarship to the University of Illinois, where he captained the basketball team and earned All Big-Ten status. After graduating in 1962 he eventually found work with the NBA’s Chicago Bulls and rose quickly through front-office positions. By the time he left the Bulls six years later, Colangelo was the franchise’s director of marketing and its chief scout.

In 1968, the expansion Phoenix Suns basketball franchise hired the 29-year-old Colangelo as their first general manager, making him the youngest in major professional sports. Colangelo transformed the Suns into one of professional basketball’s best managed and most consistently successful franchises. During his 35 years as a Suns executive, the team was a fixture in the Western Conference playoffs and played to large, boisterous crowds, first at the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum on the State Fairgrounds and then at the downtown America West Arena. Despite never winning the championship, Colangelo earned numerous NBA Executive of the Year Awards, acknowledging both his franchise’s success and his status as a mover and shaker in league circles.9

In 1987 Colangelo headed a 10-member limited partnership called JDM Partners LLC that purchased the Suns for $44.5 million. The move came soon after a drug scandal that threatened the franchise’s squeaky-clean image. Colangelo cleaned house quickly and soon restored the Suns to on-court success; they put together a franchise-record streak of seven consecutive 50-win seasons between 1988-1989 and 1994-1995. Colangelo also negotiated a financing deal for a new arena to be built primarily with private money raised through JDM’s limited partners and corporate sponsorship deals. America West Arena, the Suns’ new downtown home, opened in June 1992. Bearing the name of a Phoenix-based airline, it was one of the earliest examples of stadium naming rights being sold to a corporation.10

In September 1993 Colangelo announced the formation of Arizona Baseball Inc., whose purpose was to bring a major-league baseball team to Phoenix. Colangelo’s insider status made Arizona’s bid an immediate frontrunner in the expansion chase. As an NBA executive, he ran in similar circles with MLB executives. More than just a known commodity, Colangelo had the added advantage of being close personal friends with Chicago White Sox and Chicago Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf, who actively championed Arizona’s bid. More than two dozen limited partners bought into Arizona Baseball Inc., including executives at Bank of America, Circle K, and Phoenix radio station KTAR, trucking magnate and future Phoenix Coyotes owner Jerry Moyes, comedian Billy Crystal, and Phoenix Suns All-Star Danny Manning.11

Colangelo set to work negotiating a financing deal for a downtown ballpark. His opposite number was Jim Bruner, a member of the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors, who also constituted the Maricopa County Stadium Authority. Despite his enthusiasm for bringing big-league baseball to the region, the fiscally conservative Bruner drove a hard bargain. He made it clear to Colangelo that there would be no increase in the 0.25 percent sales tax unless Maricopa County residents received a good deal on the facility. Colangelo agreed to a set of terms that saved Maricopa County taxpayers more than $40 million on the facility.12

The stadium financing deal Bruner and Colangelo worked out capped Maricopa County’s sales tax contribution at $238 million. It gave ownership of the ballpark to the county and guaranteed the county one-third of the annual earnings from naming rights. (In 1998 Bank One acquired the naming rights for 10 years at a cost of $70 million.) The financing deal provided the county with an escalating annual revenue guarantee based on ticket sales while requiring the Diamondbacks to pay for the maintenance of the ballpark. In return, the county granted the baseball team a 30-year lease and primary-tenant status. Despite some misgivings, Colangelo agreed to the deal. He realized that if he alienated an ally like Bruner, the political pressure that other county supervisors would face from a public that less than five years earlier had turned down a stadium financing referendum would likely push their votes into the “no” column.13

Maricopa County tax assessors projected that revenue from the 0.25 percent sales tax would reach its $238 million target in approximately 2½ years, and the tax would end around the time the ballpark was slated to open in March 1998. In fact, the target was reached four months earlier than expected, in November 1997, two years after construction began on the 48,500-seat domed stadium and four months before the first pitch.14

But even with the taxpayer-friendly amendments to the deal, widespread opposition emerged almost immediately to the public financing of a ballpark without voter input. Many opponents decried what they perceived as collusion between the city’s political and business elite. More than 800 residents, split roughly evenly between supporters and opponents, attended the February 1994 meeting at which the Board of Supervisors voted amid a heavy police presence on the stadium deal.15

After a contentious six-hour meeting, the Supervisors voted 3 to 1 with one recusal to impose the sales tax. Colangelo, the public face of the stadium project, skipped the meeting. His presence would likely have galvanized the already stinging criticism that he and pro-stadium legislators had already faced as a result of the deal. Long the darling of the Phoenix media, Colangelo had never experienced citizens referring to him in letters to the editor or public meetings as a “thief” or claiming that he was trying to “rape” the taxpayers. Jim Bruner, who both helped to develop the plan to pursue a baseball team and negotiated the terms of the financing deal with Colangelo, cast the deciding vote for the measure.16

The three supervisors who supported the tax faced serious consequences. After the vote, Bruner, as he had planned, resigned from the board to run for an open congressional seat. He lost in the Republican primary to attorney John Shadegg, who transformed the campaign into a virtual referendum on Bruner’s support for the stadium tax. Pro-sales-tax Supervisor Ed King lost his bid for re-election in 1996 in a campaign that focused heavily on his support for the tax.17

More than three years after the vote, in August 1997, Supervisor Mary Rose Wilcox, the lone Democrat on the Board of Supervisors, who voted to impose the tax, was shot in the lower back after a Supervisors meeting by a man described as mentally deranged. The attacker told the press, “I shot Supervisor Mary Rose Wilcox to try to put a stop to the political dictatorship of Jerry Colangelo in pushing the baseball stadium tax.” Wilcox survived the attack, which she blamed on the harsh opposition to the tax that remained a fixture of Phoenix talk radio.18

Ballpark deal in hand, Colangelo made his expansion pitch to major-league owners in February 1994. He emphasized the booming population of metropolitan Phoenix, the region’s history of enthusiastic support for collegiate, spring-training, and Fall League baseball, and his history of managerial success with the Suns.19 A few days later the owners awarded Arizona Baseball Inc. an expansion franchise. (They also awarded a franchise to a Tampa-St. Petersburg-based ownership group led by businessman Vincent J. Naimoli.) They were to begin playing in the 1998 season.

After a 1995 “name the team” contest conducted by the Arizona Republic in 1995, the nickname Diamondbacks was chosen for the team. The Diamondbacks adopted a quintessentially late 1990s palette of team colors: purple, turquoise, black, and copper. The colors were marketed as evocative of the region’s cultural heritage. Collectively, the color scheme adopted by the Diamondbacks, or “DBacks,” as they were soon dubbed by the local media, looked similar to the colors of Colangelo’s other team, the Suns, whose stature in the region was then at its peak. Colangelo persuaded the other partners in Arizona Baseball Inc. to call the team the Arizona Diamondbacks rather than the Phoenix Diamondbacks to cultivate a statewide sense of pride and ownership. Moreover, the “Arizona” branding of the Diamondbacks was in keeping with the previous round of baseball expansion, which brought the Florida Marlins and Colorado Rockies into existence.20

As general manager the Diamondbacks in June 1995 hired Joe Garagiola Jr., one of the founding fathers of big-league baseball in Phoenix. Later that year, Colangelo and Garagiola hired Buck Showalter as the club’s first manager. Showalter came aboard just days after the New York Yankees fired him in the wake of the team’s playoff loss in its first postseason appearance in 14 years. Like many of his predecessors in New York, the intense Showalter butted heads frequently with the club’s domineering owner, George Steinbrenner. The Diamondbacks gave Showalter the additional responsibility of overseeing the development of its minor-league system. The Diamondbacks fielded their first affiliated minor-league teams in 1996. In subsequent seasons Showalter clashed with Garagiola over the direction of the club. Showalter preferred a steady player-development program through a farm system while Garagiola adopted the “win-now” (meaning sign free agents) approach favored by Colangelo. As a result, Showalter was fired after the 2000 season.21

The “win-now” approach was clearly the governing ideology of the Diamondbacks by the time of the November 18, 1997, expansion draft. Colangelo believed that taxpayers deserved an immediately competitive club in return for the investment they had made in Bank One Ballpark. Moreover, he believed that unless the Diamondbacks fielded an immediately competitive team, they would not gain a foothold in the increasingly tight market for Arizona sports fans’ dollars. By the time the Diamondbacks played their first game at Bank One Ballpark, metropolitan Phoenix was home to teams in all four major professional leagues. In the expansion draft, the Diamondbacks scooped up veteran starting pitchers Brian Anderson and Jeff Suppan with their first two picks. After the draft they traded several of the prospects they had selected for veterans like Detroit Tigers third baseman Travis Fryman and Florida Marlins center fielder Devon White. During the 1997-98 baseball offseason, the Diamondbacks acquired high-profile, high-priced free agent shortstop Jay Bell and traded for third baseman Matt Williams.22

The Diamondbacks doubled down on the “win-now” approach in their early years, signing pitching aces Randy Johnson in 1999 and Curt Schilling in 2000 to long-term deals that deferred the big payments until the latter years of their contracts. The Diamondbacks’ willingness to invest heavily in elite starting pitching put them on the fast track to the postseason. They finished first in the NL West in 1999, their second season in the major leagues. Never before had an expansion team reached the playoffs so quickly. Two years later, Johnson and Schilling anchored the team that won the 2001 World Series against the Yankees.23

The Diamondbacks’ success helped them draw large crowds even after the honeymoon of their first season. More than 2.5 million people attended games at the Bank One Ballpark (nicknamed the BOB) in each of the franchise’s first seven seasons. Initially, the BOB proved to be its own draw with an unprecedented array of amenities that appealed to spectators who were not especially interested in baseball: several playgrounds, a picnic pavilion, a day spa, and a swimming-pool party area (which could be rented for a group of up to 30 for $4,000 per game) were among the most popular attractions. The ballpark’s retractable roof allowed fans to enjoy the sun while sitting in air-conditioned comfort. Additionally, the BOB offered some of the most affordable prices in baseball. In the late 1990s, a family of four could attend a game for well under $50, including tickets, parking, and refreshments.24

On game days, thousands of suburbanites who would likely not have otherwise patronized downtown Phoenix brought their discretionary dollars to the BOB and its environs. The presence of the Diamondbacks hardly transformed commercial or residential patterns in Maricopa County. According to a 2015 study commissioned by the Diamondbacks, the franchise generated $8.2 billion in economic activity since it began in March 1998. This is less than 0.5 percent of the total economic activity in Maricopa County in that same time period. Nevertheless, Bank One Ballpark has contributed to the revitalization of downtown Phoenix. During the 1960s suburban shopping centers replaced downtown Phoenix as the region’s retail center. But the downtown area slowly emerged from its doldrums, becoming a destination to visitors outside of banker’s hours. The creation of a number of new institutions and attractions in downtown Phoenix added vibrancy to the once moribund area. In addition to the BOB, Maricopa County taxpayers subsidized municipal bonds that financed the construction of a number of other downtown attractions during the 1990s, including a new library, a science center, an art museum, and a museum of Arizona history.25

The success the Diamondbacks enjoyed during their early years came at a high price. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the franchise signed high-priced free agents to large contracts that deferred large amounts of salary. Between 1998 and 2000, the Diamondbacks more than doubled their payroll from $32 million to $80 million. The 2001 World Series-winning team had an $84 million payroll, of which $46 million was deferred. To pay off the deferred salaries, the Diamondbacks raised ticket prices sharply in the early 2000s and eventually traded Schilling to the Boston Red Sox in November 2003 and Johnson to the New York Yankees in December 2004 for prospects and cash. By the end of the 2004 season, the club owed more than a quarter of a billion dollars in deferred salaries.26

Displeasure with the direction of the franchise led to Colangelo’s ouster as managing general partner by the other four general partners in Arizona Baseball Inc. in August 2004. Garagiola followed Colangelo out the door in 2005. Ken Kendrick, who had been a managing partner since the franchise’s origins, took over as managing general partner. As of 2016 Jeffrey Royer, Michael Chipman, and Dale Jensen remained the other general partners.

A native of West Virginia, Kendrick made his fortune in the software business as the founder of Datatel Inc., a Virginia-based company that provided high-tech services and software to colleges and universities. He and his wife, Randy, have long been conservative political activists. In recent years, they have worked closely with the Koch political organization. During the 2016 Republican presidential primaries, the Kendricks made headlines in Arizona for their strident opposition to Donald Trump’s bid for the nomination. Like Kendrick, Jensen and Chipman earned their fortunes in the software industry. Jensen is the co-founder of Information Technology, which develops software for the banking industry. Chipman was the creator and original owner of TurboTax. Royer was an executive in the cable television industry.27

A native of West Virginia, Kendrick made his fortune in the software business as the founder of Datatel Inc., a Virginia-based company that provided high-tech services and software to colleges and universities. He and his wife, Randy, have long been conservative political activists. In recent years, they have worked closely with the Koch political organization. During the 2016 Republican presidential primaries, the Kendricks made headlines in Arizona for their strident opposition to Donald Trump’s bid for the nomination. Like Kendrick, Jensen and Chipman earned their fortunes in the software industry. Jensen is the co-founder of Information Technology, which develops software for the banking industry. Chipman was the creator and original owner of TurboTax. Royer was an executive in the cable television industry.27

Colangelo’s tenure as managing general partner (1998-2004) coincided largely with Joe Garagiola Jr.’s term as general manager (1997-2005). Under Colangelo and Garagiola, the Diamondbacks won division titles in 1999 and 2001 as well as the pennant and World Series in 2001. Under Kendrick’s leadership, the Diamondbacks have enjoyed significantly less success on the field. But the franchise did succeed in getting a handle on its salary situation, and from about 2005 it has ranked near the bottom of the league in payroll most years. Such austerity did not breed a great deal of on-the-field success. The Diamondbacks won the NL West in 2007 and 2011, but more often than not have finished well out of contention, including at least three last-place finishes since 2009. The “win-now” approach of the Colangelo-Garagiola era can take some of the blame for the diminishing returns. The franchise’s financial situation and farm system were in difficult straits at the time of the original regime’s departure, but for for more than a decade this has been Kendrick’s franchise. Since 2005 the Diamondbacks have gone through five general managers: Bob Gebhard (2005), Josh Byrnes, (2005-2010), Jerry Dipoto (2010), Kevin Towers (2010-2014), and Dave Stewart (2014-). The leadership of former pitching ace Dave Stewart and Hall of Fame manager Tony La Russa, has as of 2016 failed to turn around the fortunes of the franchise, finishing well out of contention in all three seasons of their tenure.28

Since Kendrick became managing general partner, the Diamondbacks have moved into a new spring-training facility, the architecturally striking Salt River Fields at Talking Stick, an 11,000-seat facility in Scottsdale that they share with the Colorado Rockies. Opened in 2011, the facility is on land owned by the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community. Like Scottsdale itself, Talking Stick evokes the Old Southwest with its homages to mission revival architecture, sagebrush surroundings, and views of Camelback Mountain. Like other new spring-training facilities in Arizona, Talking Stick was subsidized in large part by the $2.50 rental-car tax that was put in place back in 1990 to revitalize the ballparks of the Cactus League.29

In 2005 Bank One merged with J.P. Morgan Chase, and Bank One Ballpark was renamed Chase Field. In 2016 Kendrick and the Diamondbacks organization were engaged in contentious negotiations with the Maricopa County Stadium Authority over the future of Chase Field. The Diamondbacks assert that Chase Field needs significant upgrades or replacement after nearly two decades of use. In March 2016 Kendrick made public his belief that the Diamondbacks needed a new ballpark, and presented a preliminary proposal to county officials. But the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors made it evident that they had no interest in supporting any such municipal investments, particularly when Major League Baseball deemed Chase Field acceptable to host its All-Star Game as recently as 2011. In the summer of 2016 the Diamondbacks asked Maricopa County for help in subsidizing $65 million worth of renovations to Chase Field, which county officials have also rejected.30

Last updated: November 28, 2017

CLAYTON TRUTOR is a history instructor at Northeastern University’s College of Professional Studies. He is also a PhD candidate in US History at Boston College. He has participated in SABR’s Biography Project since 2012. He is a staff writer for “Down the Drive,” SB Nation’s University of Cincinnati athletics website. You can follow him on twitter @ClaytonTrutor.

Photo credits

2015 Chase Field photo by Jacob Pomrenke/SABR.

Jerry Colangelo photo on March 22, 2017, was taken by Gage Skidmore. Used by permission under Creative Commons license (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Ken Kendrick photo courtesy of the Arizona Diamondbacks.

Notes

1 Rick Thompson, “A History of the Cactus League,” Spring Training Magazine, March 1989. Accessed on June 17, 2016: springtrainingmagazine.com/history4.html#cactus ; Gary Rausch, “The Cactus League Is a Major League Tourist Attraction in Arizona,” Chicago Tribune, February 26, 1989, M23.

2 Ibid. Thompson, “A History of the Cactus League.”

3 Rick Hummel, “Cactus League Is Coming on Strong,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 7, 2010, C1; Ron Fimrite, “The Selling of Spring,” Sports Illustrated, March 27, 1989, 58-61.

4 Raymond Schultze, “Stadium Developer Quits Deal,” Phoenix Gazette, May 27, 1988, A1, A11; David Schwartz, “Martin Stone Quits Pact for ‘Dome’; Plan in Peril,” Arizona Republic, May 27, 1988, A1, A8; Christopher Broderick, “Agreement Reached on Stadium,” Arizona Republic, April 10, 1987, A1.

5 Martin Van Der Werf, “Martin Stone,” Arizona Republic, March 12, 1995, BB2; “Stadium Developer Quits Deal”; “Martin Stone Quits Pact for ‘Dome’; Plan in Peril”; “Agreement Reached on Stadium.”

6 Robert Barrett, “Stadium Fails, Goddard Wins,” Arizona Republic, October 4, 1989, A1.

7 “Martin Stone”; Bob Cohn, “Race for Big Leagues Begins,” Arizona Republic, June 15, 1990, A1; Eric Miller, “Valley Strikes Out,” Arizona Republic, December 19, 1990, A1.

8 John Walters, “Brazen Arizona,” Sports Illustrated, January 29, 1996, 190-194.

9 Robert Logan, “Colangelo Quits Bulls to Take Phoenix Post,” Chicago Tribune, February 29, 1968, C1; Bob Logan, “Colangelo Has Suns Climbing for Summit,” Chicago Tribune , May 23, 1976, B3; Lee Shappell, “Jerry Colangelo,” Arizona Republic, March 12, 1995, BB2; “Colangelo Took Bait All the Way to Finals”; Kevin Simpson, “The Place to Be,” The Sporting News, November 7, 1994, S3; Jack McCallum, “Desert Heat,” Sports Illustrated, May 28, 1990, 50-51; Joe Gilmartin, “Suns’ Colangelo NBA Executive of the Year,” The Sporting News, May 16, 1981, 46.

10 “NBA Notebook: Pacific,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1987, 47; Steve Wilson, “When You’re Colangelo, You Gotta Believe,” Arizona Republic, January 16, 1994, 10; Norm Frauenheim, “Colangelo-Led Group Buys Phoenix Suns,” Arizona Republic, October 13, 1987, A1, A2.

11 “Baseball Panel Backs Phoenix, Tampa Bay,” Arizona Republic, March 8, 1995, A1, A16; “DBacks Ownership a Mixed Bag,” Arizona Republic, March 30, 1998, C33; Richard Obert, “Floating on Air, Colangelo Readies Big Party Today,” Arizona Republic, March 11, 1995, C1.

12 Mike Padgett, “Decision Cost Jim Bruner His Dream of Serving as U.S. Congressman,” Phoenix Business Journal, March 26, 2008. Accessed June 10, 2016: http://bizjournals.com/phoenix/stories/2008/03/31/story7.html.

13 David Schwartz and Eric Miller, “County Close to Deal on Ballpark,” Arizona Republic, January 9, 1994, A1; Frank Fitzpatrick, “Stadium Issues Can Explode: Take Phoenix,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 13, 1999, E1; “Decision Cost Jim Bruner His Dream of Serving as U.S. Congressman”;

14 “Decision Cost Jim Bruner His Dream of Serving as U.S. Congressman.”

15 “County Close to Deal on Ballpark.” “Decision Cost Jim Bruner His Dream of Serving as U.S. Congressman.”

16 David Fritze, David Schwartz, and Eric Miller, “Play Ball: Stadium Tax Wins OK,” Arizona Republic, February 18, 1994; “Jerry Colangelo”; Bob McManaman, “Tax Foes’ Name-Calling ‘Hurt Deeply,’” Arizona Republic, February 19, 1994, A20.

17 “County Close to Deal on Ballpark”; Arizona Republic, January 9, 1994, A1; David Schwartz and Eric Miller, “Negotiators Strike Deal on Big-League Ballpark,” Arizona Republic, January 15, 1994, A1; “Decision Cost Jim Bruner His Dream of Serving as U.S. Congressman.”

18 Mike McCloy, “Supervisor Is Shot,” Arizona Republic, August 14, 1997, A1, A12; William Hermann, Susie Steckner, and Mike McCloy, “Suspect: Tax Spurred Shooting,” Arizona Republic, August 14, 1997, A1, A12; Mike McCloy, “Wilcox Snags 50 Tickets for Opening,” Arizona Republic, March 31, 1998, A1; Mike McCloy, “‘Guy has a Gun’: Guard Acted Fast,” Arizona Republic, August 15, 1997, A1; Frank Fitzpatrick, “Stadium Issues Can Explode: Take Phoenix,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 13, 1999, E1.

19 Bob McManaman, “Colangelo Winds Up to Make Big Pitch,” Arizona Republic, February 19, 1994, A1, A20.

20 “Brazen Arizona.”

21 Murray Chass, “Arizona Gets Set to Hire Showalter,” New York Times, November 12, 1995, 42; Howard Fendrich, “Diamondbacks, Yankees Found Success After Showalter Left,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 25, 2001. Accessed June 10, 2016: http://seattlepi.com/sports/baseball/article/Diamondbacks-Yankees-found-success-after-1069899.php

22 Ken Rosenthal, “All Arizona Has to Do Now, Right Now, Is Win,” The Sporting News, March 12, 2001, 49; Peter Schmuck, “In Hurry, a Trading Flurry After Draft,” Baltimore Sun, November 19, 1997. Accessed June 10, 2016: http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1997-11-19/sports/1997323118_1_red-sox-pedro-martinez-rosters.

23 “Floating on Air, Colangelo Readies Big Party Today”; Pedro Gomez, “Tickled to Be in Arizona,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1998, 80; “All Arizona Has to Do Now, Right Now, Is Win.”

24 Mike McCloy, “Ballpark Looks Like a Million,” Arizona Republic, October 13, 1996, B1; Don Ketchum, “In the Ballpark,” Arizona Republic, November 16, 1995, D4; “Come Along on a BOB Tour,” Arizona Republic, March 22, 1998, A1; Martin Van Der Wert, “1st Year Is a Tryout for Cooling System,” Arizona Republic, March 22, 1998, BP6; “Family-Style Attractions Cover All the Bases,” Arizona Republic, March 22, 1998, BP10; Bill Muller, Mark Shaffer, and Richard Ruelas, “BOB Takes a Bow,” Arizona Republic, March 30, 1998, A1; Linda Helser, “Diamondbacks May Be Best Pro Sports Bargain in Valley,” Arizona Republic, March 29, 1998, C37; Pedro Gomez and Mark Topkin, “Scouting the Expansion Cities,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1998, 26; “Fans Guide: Ticket Prices,” March 30, 1998, Arizona Republic, C41

25 “Arizona Diamondbacks Letter to Maricopa County Board of Supervisors, January 12, 2016,” BallparkDigest.com, March 30, 2016. Accessed August 3, 2016: http://ballparkdigest.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/OriginalDbacksletterforChairmanSupervisors03242016.pdf ; “Maricopa County Stadium District: Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,” Maricopa.gov, June 30, 2013. Accessed August 3, 2016: http://maricopa.gov/StadiumDistrict/pdf/MCStadiumDistFY12AFR.pdf; David Fritze, “Boom! Downtown May Fully Awaken,” Arizona Republic, March 12, 1995, BB7.

26 “All Arizona Has to Do Now, Right Now, Is Win”; Nick Piecoro, “Jerry Colangelo’s Shadow Remains Prominent Over Diamondbacks,” azcentral.com, September 27, 2014. Accessed June 3, 2016: http://azcentral.com/story/sports/mlb/diamondbacks/2014/09/27/jerry-colangelos-shadow-remains-prominent-diamondbacks/16344607/.

27 “Jerry Colangelo’s Shadow Remains Prominent Over Diamondbacks.”

28 Ibid.

29 “Cactus League Stadium Guide: Salt River Fields at Talking Stick,” FoxSports.com, February 24, 2016. Accessed June 3, 2016: http://foxsports.com/arizona/story/cactus-league-stadium-guide-salt-river-fields-arizona-diamondbacks-colorado-rockies-022416 ; “Cactus League: Salt River Fields,” azcentral.com, February 24, 2016. Accessed June 3, 2016: http://azcentral.com/story/entertainment/events/2015/02/25/cactus-league-stadium-guide-salt-river-fields-at-talking-stick/24009267/ .

30 Rebekah L. Sanders, “Maricopa County Rejects Most of Arizona Diamondbacks’ Requested $65M for Upgrades,” azcentral.com, August 8, 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016: http://azcentral.com/story/news/local/phoenix/2016/08/08/maricopa-county-rejects-most-diamondbacks-request-65-million-chase-field-upgrades/88279408/.