Baseball’s Integration Spells the End of the Negro Leagues

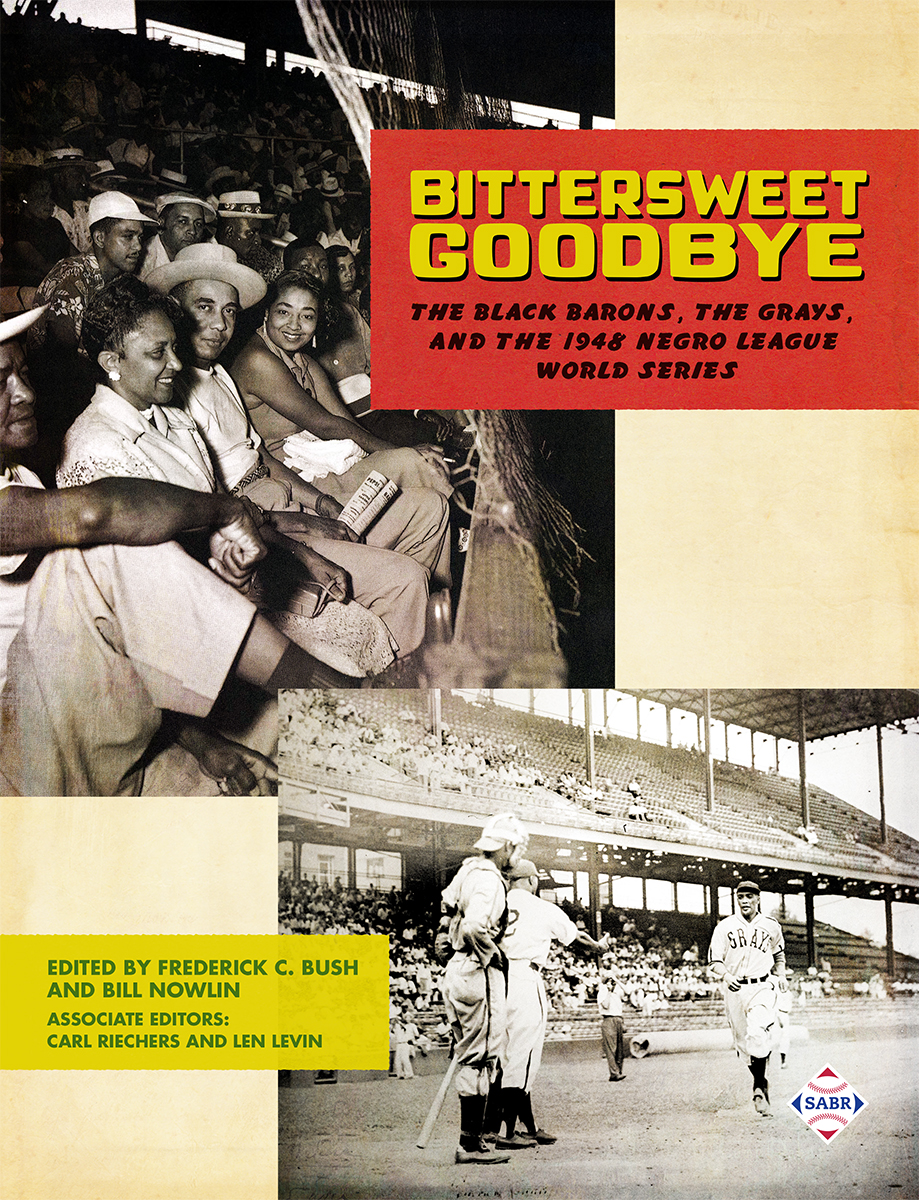

This article was originally published in SABR’s Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series (2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

It has been asserted that baseball makes an effective metaphor for the history of the United States, reflecting the changing circumstances and values of American society.1 If such is the case, then the decline and end of the Negro Leagues may provide insights about the changing realities for urban African-Americans in the years after World War II. Shifting political and economic opportunities, and the limits of those opportunities, have had a profound effect on American society, especially for African-Americans, over the course of the last eight decades. The early stages of integration in American society brought with it new hopes for marginalized minority groups; however, it also posed new challenges. Traditionally black-owned enterprises – among them the Negro Leagues – now faced increased competition for black workers and revenue and had difficulties maintaining sustainable businesses, which resulted in the failure of most medium and large-scale black firms during the mid-twentieth century.

It has been asserted that baseball makes an effective metaphor for the history of the United States, reflecting the changing circumstances and values of American society.1 If such is the case, then the decline and end of the Negro Leagues may provide insights about the changing realities for urban African-Americans in the years after World War II. Shifting political and economic opportunities, and the limits of those opportunities, have had a profound effect on American society, especially for African-Americans, over the course of the last eight decades. The early stages of integration in American society brought with it new hopes for marginalized minority groups; however, it also posed new challenges. Traditionally black-owned enterprises – among them the Negro Leagues – now faced increased competition for black workers and revenue and had difficulties maintaining sustainable businesses, which resulted in the failure of most medium and large-scale black firms during the mid-twentieth century.

For decades, major-league baseball has taken pride in (and rarely failed to publicly point out the fact that) it was a leader in desegregation in the United States, hiring first Jackie Robinson and then numerous other African-American players several years before the civil rights movement began in earnest. However, recent scholarship suggests that this assessment is in error. The traditional narrative of the civil rights movement being mostly restricted to the American South and taking place largely in the 1950s and 1960s has undergone a thorough reassessment. The new paradigm, which views the struggle for civil rights as much lengthier and taking place in Northern urban areas, has altered the understanding of African-American history and has changed the way in which the period of baseball’s integration and decline of the Negro Leagues is viewed.2

The era of baseball’s integration can be reexamined as part of a broader movement toward increased civic, educational, and economic rights that became available to African-Americans in the 1930s and 1940s. Organizations like the Congress of Racial Equality and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People were extremely active in this period as they pressured political leaders, influenced public sentiment, and used the courts to gain access to better-paying jobs and schools. With the onset of World War II, the nascent civil rights movement was able to harness national rhetoric about combating fascism to push for greater equality on the home front. Activities like the Double V Campaign (for victory against oppression both abroad and at home) and a call for a march on Washington by black leaders helped lead to increased hiring and better wages during the war. However, when wartime industrial production was cut after the end of the war in 1945, black workers once again faced a “last hired, first fired” mentality and an uncertain role in the postwar economy.3

Baseball was not unique among professional sports for signing black athletes around this time. The National Football League integrated in 1946 when the Los Angeles Rams, facing mounting public pressure for not hiring black players while playing in a publicly owned and financed stadium, signed Kenny Washington, who had been Robinson’s teammate on the UCLA football squad.4 Horse racing, which had featured a number of black jockeys until around the turn of the twentieth century, had been segregated for decades but featured African-American Jimmy Thompson during the 1948 racing season.5 Black boxing officials entered the sport for the first time in May 1948 when D. Franklin Chiles served as a ring judge for five bouts at the Chicago Coliseum, including the light-heavyweight championship fight between Enrico Bertola and Jimmy Roberts, and Bill Dody refereed three of the matches.6 The National Basketball Association was desegregated in 1950 when Earl Lloyd of the Washington Capitals became the first African-American in that circuit. Professional golf and tennis integrated in 1948 and 1950, respectively.7 Thus, while Robinson’s signing to a minor-league contract in October 1945 was the first breach in the color wall of professional sports, it soon became part of a movement in postwar America rather than a singular event.

The famous story of Branch Rickey recruiting Jackie Robinson to become the first black player in the major leagues provides an example of how opportunistic white business leaders were able to profit by the exploitation of newly available black professionals and customers while at the same time presenting their actions as affirmative and progressive. This narrative presents Rickey as a stalwart of egalitarianism who, long troubled by the color line in baseball, made the momentous decision to bring black players into the major leagues. Rickey allegedly had been appalled by the treatment of African-Americans, both in baseball specifically and American society more generally, owing to his deeply held religious views and personal experience in seeing the negative effects of discrimination. Supposedly, as a coach for Ohio Wesleyan in 1903, Rickey was traveling with the baseball team when a young black player named Charles Thompson was denied accommodation at the hotel where the team was staying. Seeing how humiliated the young man was, Rickey vowed to fight racial discrimination.8

It is a nice story, but there is serious doubt as to its veracity. Rickey never once, at least publicly, told this story between 1903 and 1945, after which it became one of his favorite and most oft-told anecdotes. There is no evidence to suggest that Rickey was a progressive on the issue of racial integration until it coincided with his self-interest.9 Indeed, Rickey himself said at the time of the Robinson signing that it was merely a baseball and business decision that would produce results (i.e., wins and increased profits) and that “I will happily bear being a bleeding heart, a do-gooder, and that humanitarian rot.”10 As time passed, the story presented by Rickey and, later, Hollywood evolved into one that presented him as a forward-thinking champion of equality rather than an opportunistic businessman.

Rickey was not the first member of major-league management to advocate the hiring of black players. John McGraw of the New York Giants had lobbied for years during the 1910s and 1920s to integrate baseball and had gone so far as to sign a light-skinned black player whom he attempted to pass off as an American Indian.11 In 1941, Dodgers manager Leo Durocher had been chastised by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis for making public comments in which he lamented his inability to sign black players (the official line of baseball was that there was no color barrier and that any team was free to sign any player it chose; it just so happened that none ever hired black players).12

The most ambitious attempt to desegregate the game was Bill Veeck’s attempt to purchase the Philadelphia Phillies in 1943. Veeck intended to dump most of the perennially awful Phillies roster, and then planned to stock the team with Negro League all-stars.13 Arrangements had already been made to buy the team and to sign, among others, Satchel Paige, Monte Irvin, and Roy Campanella. When word reached league officials, the sale was voided by National League President Ford Frick; in what was almost certainly an illegal act of collusion, the Phillies then were sold to another bidder at a lower price.14

Rickey had been an executive in baseball for more than 30 years before he signed Robinson. He had previously served as the general manager of the St. Louis Browns and St. Louis Cardinals and in neither of those roles had ever so much as hinted at a desire to bring in black players, though St. Louis certainly did not provide an environment that would have welcomed the integration of baseball. Indeed, Sportsman’s Park, where both teams played, was the last major-league stadium to desegregate its seating, and it did not do so until Rickey had moved on to Brooklyn.15 What had been well-known about Rickey in baseball circles for decades, however, was his ability to find new sources of talent that had been untapped by other clubs in order to build championship teams at bargain prices. In St. Louis he had developed what became known as the farm system which provided his teams with a continuous stream of talent and allowed him to keep his players’ salaries at below-market prices.16

For any manager keen to exploit new pools of talent at minimal prices, using black players in postwar New York was a shrewd move. Brooklyn was likely the most racially and economically diverse of all major-league markets at this time. Also, by not hiring black players, the Dodgers, Yankees, and Giants were all technically breaking New York state law. The Quinn-Ives Act imposed a fine of up to $500 or imprisonment for one year or both for any employer who refused to hire a person based on race.17 While this law was seldom enforced, and never was applied to professional baseball, there was a groundswell of public support in favor of integration. In New York there were frequent protests of all three major-league teams led by groups like the Congress of Racial Equality that brought out hundreds (and occasionally thousands) of pickets. Local politicians, including Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, campaigned on the issue.18 Clearly, Rickey’s decision to bring a black player to the Dodgers did not happen in a vacuum.

After Jackie Robinson broke the color line, executives and owners from the Negro Leagues met with their counterparts from the major leagues and proposed a number of options for mergers and cooperation. At first it was suggested that the better clubs with large fan bases from the Negro Leagues, such as the Kansas City Monarchs, be allowed in as expansion franchises.19 Several of these teams operated in cities that lacked a major-league team, already had large followings, and were perfectly positioned to help the major leagues take advantage of postwar prosperity and newly expendable income. The proposal was unanimously voted down. When this was rejected the possibility of the Negro Leagues becoming a Triple-A minor-league circuit was raised, but this idea also was summarily dismissed.20 White owners had no interest in cooperating with their black counterparts and made a deliberate choice to put the Negro Leagues out of business after obtaining their best players and wooing away much of their fan base.

The fact that the major leagues wanted only the best Negro League players was due largely to the common practice of using racial quotas; most franchises kept roster spots for African-American players to a minimum (often only two per team). Black players were nearly always signed in even numbers, so that their white teammates would not have to share rooms with them on the road.21 It was not unusual to see a black player traded or sent to the minors if there were “too many” black players on the squad.22 Slots for journeymen and utility players were still, for the most part, the territory of white players. The message to black players was clear: produce more than the average white player or lose your roster spot on the team.

Somewhat paradoxically, the years between 1947 and 1950 – as Negro League attendance dropped off dramatically due to the loss of star players – were some of the most financially successful for some black teams, among them the Birmingham Black Barons and the Kansas City Monarchs. However, this was due primarily to the sale of players to white-owned teams.23 The Monarchs were also among the first teams to begin consciously scouting prospects for sale to affiliated white clubs rather than to developing them for their own roster. This had the effect of further distancing an already dwindling fan base. Black franchises saw their values plummet, with teams that had been worth millions at the close of World War II going out of business by the end of the decade.24

To complicate matters further, a number of white teams refused to honor Negro League contracts and pirated players outright without compensating Negro League team owners.25 Rickey, while gaining esteem among many African-Americans (and earning the animosity of others) for the signing of Robinson, paid the Monarchs nothing for Robinson’s contract, stating that Negro League contracts were not in accordance with the National Agreement that governed all affiliated baseball contracts and were therefore void.26 Teams began to sell their players for a fraction of their market value in order to recoup some of their investment rather than to take a total loss on a player who jumped his contract.27

As the 1948 season began, many observers in the black community were reeling from the previous year’s dramatic drop in attendance and were uneasy about the future of black baseball. Increased competition from major-league clubs with African-American players was the primary factor involved, though it was certainly not the only one. Radio and, to a limited extent, television were allowing people to experience the game without paying to get into the ballpark; no longer did proximity limit fans’ choice of which team to root for as their favorite. New forms of entertainment had become available, especially after the wartime rationing of resources was lifted, and as competition for the black entertainment dollar had increased, Negro League teams already had started to see a decline in attendance in 1947. Now they were fearful about a future in which all the best black players were on major-league teams and were taking their fans with them.

At the same time that attendance at Negro League games was shrinking, patronage of Organized Baseball-affiliated teams was reaching record highs, at least in part due to the new influx of African-American players. The Cleveland Indians, with two black stars in Larry Doby and Satchel Paige, set a new major-league attendance record in 1948 with attendance of 2,620,627. Minor-league teams were also seeing increased fan support, with the Triple-A American Association setting a new record for league attendance that summer.28 The St. Paul Saints, who finished third in American Association attendance, with 320,483 fans turning out, fielded the league’s first black player that season, pitcher Dan Bankhead of the Dodgers organization, who drew large crowds of black fans whenever he pitched.29 The effects of employing black ballplayers to draw new black fans were instant and profound.

In the now rapidly declining Negro Leagues, the most vocal owner to voice concern about the uncertain financial future of the leagues’ teams was Newark Eagles co-owner Effa Manley. In September 1948, she publicly discussed the likelihood of the Eagles being sold or shutting down entirely due to a precipitous drop in revenue since the 1946 season. She blamed the fans for being fickle and said, “Most of our old fans are going to see four men with white teams who played on our teams for years without exciting their present intense interest.”30 Black players were tired of feeling they were being taken for granted by Negro League teams and, now that they had increased options for their services, they began to be vocal about it. Jackie Robinson wrote a piece for Ebony in which he roundly criticized black baseball’s owners for their low pay, poor accommodations, and generally shoddy treatment of players.31

Members of the black press sometimes dealt with these developments in a contradictory nature. John Johnson, the longtime sports editor of the Kansas City Call, first used his column to brag about what a monetary success the integration of black players into white leagues had been for their clubs and to poke fun at those who had insisted that any such arrangement would inevitably lead to violence and rioting. Noting the new attendance records that had been set by teams in Organized Baseball since the inclusion of black players, he wrote in early September, “By box office records, Old Gus [Greenlee] is proving that the greatest single new appeal the great old game has come up with in years is the presence and play of Negro players in the Major Leagues.”32 The following week he used his space to attack Manley and her “sob solo for sympathy,” saying, “Much of the absenteeism at Negro games is due to the lack of interest due to lack of salesmanship.”33

An ardent supporter of both black baseball and the integration of the major leagues, Johnson appeared to miss the fact that the two entities were fast becoming mutually exclusive. He also took Robinson to task for his remarks, saying, “Pop-offs were as bad as pop-outs,” and that while the Negro Leagues had problems, they had given Robinson his start and he ought to have been grateful for that.34

As the postwar period continued with a housing boom in suburban areas, African-Americans once again found themselves cut out. Restrictive housing and lending policies like redlining and property covenants keep black residents restricted, at least in practice if no longer by law, to segregated neighborhoods in urban centers. As manufacturing began to follow workers out of the cities, these municipalities now had to provide for public infrastructure with a dwindling tax base, resulting in deep cuts to public amenities. During the 1960s and ’70s most of the old, downtown ballparks were demolished in the name of urban renewal with new, cavernous multi-use stadiums built usually away from the city center in acres of parking lots removed from public transit. The numbers of black players making their way to the major leagues has diminished with the lack of access to the game, despite efforts to increase play in the sport among youth.

That the 1948 Negro League World Series was the last played shortly before the collapse of the Negro National League was not an aberration but was part of a growing trend. An organized push for expanded rights and opportunities, particularly in Northern urban areas and during World War II, had helped African-Americans gain ground in American society. However, this was almost always limited and conditional, and it came at the cost of many independent black entrepreneurs. Black baseball struggled on through the 1950s, but it never approached anything near to the popularity it had enjoyed during its wartime peak. Instead of developing young talent into local stars who stayed with the club throughout their careers, Negro League teams now deliberately scouted players they could sell to the majors.

While a number of future stars like, Ernie Banks, and Hank Aaron, played in the Negro Leagues during this period, it was always known that these young men would be with their club only temporarily before moving on. When major-league teams began to scout black players on their own, even this niche began to wane. By the end of the 1950s only a handful of clubs remained in the Negro American League, and even then they played most of their games as barnstorming exhibitions. When the league folded in the early 1960s, its demise went almost unnoticed. The Indianapolis Clowns continued to play as a barnstorming squad into the 1980s, but they were little more than a vestige of the time when Negro League teams were the cornerstone of the African-American community.

JAPHETH KNOPP received his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from Missouri State University and is currently in the History Ph.D. program at the University of Missouri. A fan of the Kansas City Royals and Fukuoka Hawks, he has been a member of SABR for a number of years and has previously contributed to the Baseball Research Journal. He lives in Columbia, Missouri with his wife Rebecca Wilkinson and their son, Ryphath. He may be con- tacted at Japheth.knopp@gmail.com.

Notes

1 Jules Tygiel, Past Time: Baseball as History (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2000), x.

2 The seminal work here is Jaquelyn Dowd Hall’s 2005 article “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past,” which has led to a paradigm shift in how scholars view the beginnings of racial integration. In this construct, Jackie Robinson and the desegregation of baseball should have been expected as part of a larger pattern of black workers entering formerly exclusive occupations rather than as an aberration.

3 William Sundstorm, “Last Hired, First Fired? Unemployment and Urban Black Workers During the Great Depression,” Journal of Economic History (Vol. 52, No. 2, June, 1992): 485.

4 Fred Bowen, “Kenny Washington Paved Way for Black Players in NFL,” Washington Post, February 2014, washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/kidspost/kenny-washington-paved-way-for-black-players-in-nfl/2014/02/19/063ad55e-98c2-11e3-80ac-63a8ba7f7942_story.html?utm_term=.81a6dffc5327 accessed March 24, 2017.

5 “Lone Colored Jockey Rides in Wake of Several Who Made History in the Past,” Kansas City Call, September 24, 1948: 8.

6 “Chicago Uses First Negro Ring Officials,” Kansas City Call, May 17, 1948: 9.

7 “Integration Milestones in Pro Sports,” espn.go.com/gen/s/2002/0225/1340314.html accessed March 23, 2017.

8 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: HarperCollins, 2000), 250.

9 Mitchell Nathanson, A People’s History of Baseball (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 81.

10 William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999), 126.

11 Baseball. Netflix. Directed by Ken Burns. PBS, 1994.

12 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books, 2007), 351.

13 Bill Veeck, Veeck – As in Wreck (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1962), 170-171.

14 The main source of this account is found in Veeck’s memoirs previously cited and has become a famous story, being recounted elsewhere. However, the validity of this narrative has come under scrutiny. In “A Baseball Myth Exploded: Bill Veeck and the 1943 Sale of the Phillies” in The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History 18, 1998, David Jordan, Larry Gerlach, and John Rossi lay out a compelling argument for this event having been little more than a tall-tale spun by Veeck, who was never one to miss an opportunity for a good story.

15 Nathanson, 80.

16 Golenbock, 83.

17 Irwin Silber, Press Box Red: The Story of Lester Rodney, the Communist who Helped Break the Color Line in American Sports (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003), 74.

18 Benjamin Rader, Baseball: A History of America’s Game (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 156.

19 Rob Ruck, Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game (Boston: Beacon Press 2011), 115.

20 Ruck, 116.

21 Nathanson, 101.

22 Nathanson, 103-104.

23 Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1985), 118-119.

24 A comparative example here is the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League who were assessed at $1.5 million in 1945, and the Cleveland Indians, who were sold in 1946 for $2.2 million. The Eagles were sold after the 1948 season and folded after two years in Houston and one in New Orleans.

25 Veeck, 176.

26 Ruck, 118

27 Veeck, 177.

28 “New Record in A.A.: Attendance in the League Reaches 2,235,853, Lane Says,” Kansas City Times, September 21, 1948: 16.

29 “Many Fail to See Bankhead in K.C. Debut,” Kansas City Call, September 3, 1948: 8.

30 “May Be Last Year for Newark Eagles,” Kansas City Call, September 3, 1948: 8.

31 Jackie Robinson, “What’s Wrong With Negro Baseball?” Ebony, June 12, 1948: 13.

32 John L Johnson, “John L Johnson’s Sport Light,” Kansas City Call, September 3, 1948: 8.

33 Johnson, “John L Johnson’s Sport Light,” Kansas City Call, September 10, 1948: 8.

34 Johnson, “John L Johnson’s Sport Light,” Kansas City Call, May 21, 1948: 8.