Bud Fowler: 19th Century Black Baseball Pioneer

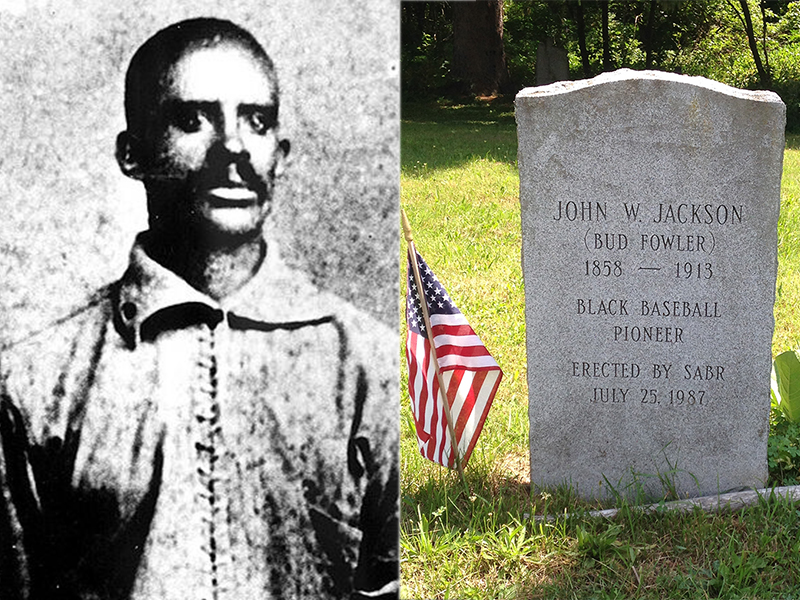

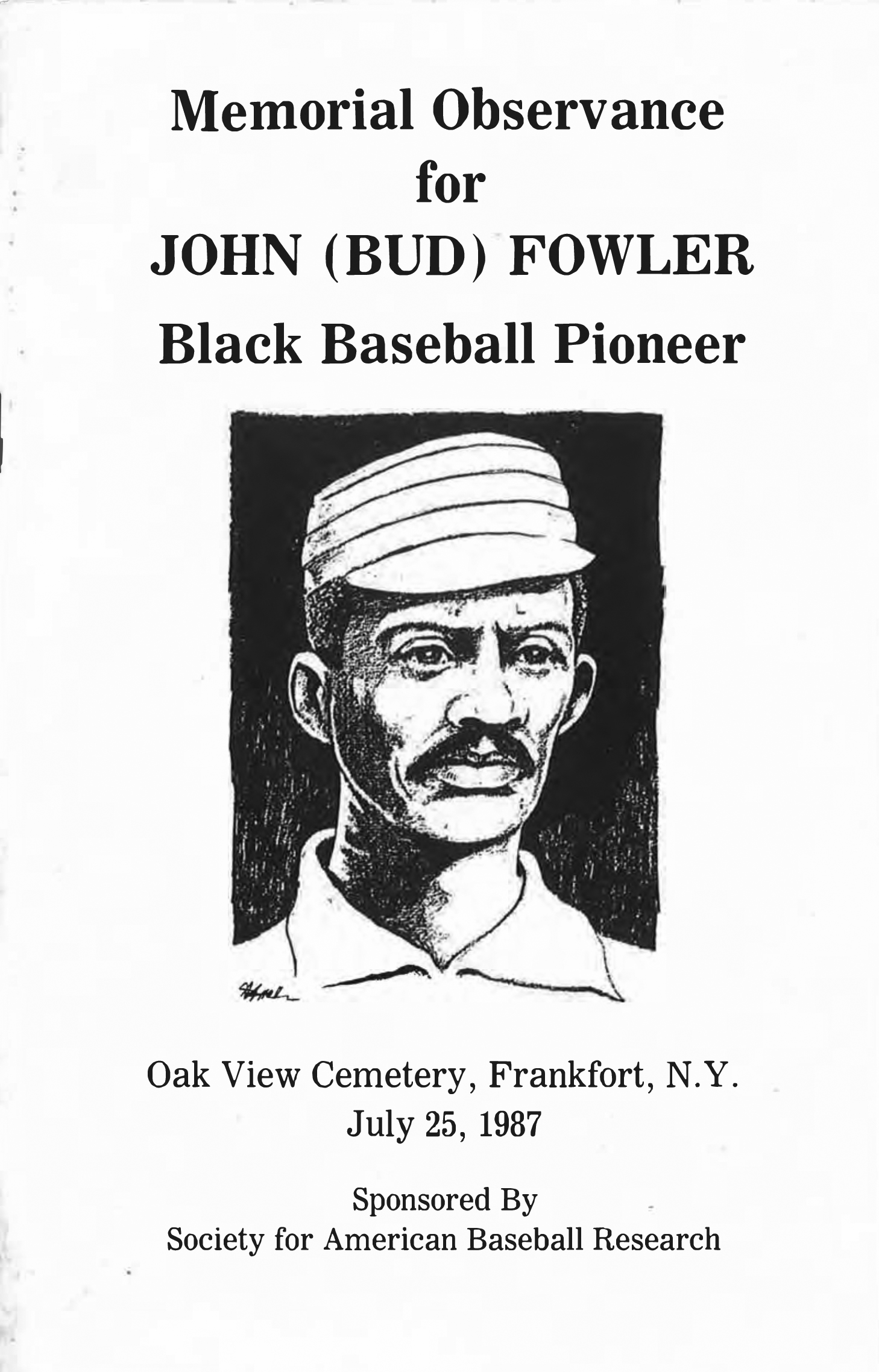

Editor’s note: On July 25, 1987, SABR placed a grave marker at the previously unmarked grave of John W. Jackson. Known in the baseball world as Bud Fowler, the New York native was a Black baseball pioneer who played, managed, and promoted teams during the late 19th century. The dedication ceremony at Oak View Cemetery in Frankfort, New York — about 30 miles north of Cooperstown — drew a crowd of more than 200 people, including Negro Leagues veterans Buck O’Neil, Monte Irvin, Larry Kimbrough, Bill Cash, and Gene Benson. SABR founder Bob Davids published the following 12-page booklet on Fowler’s life and career that was handed out to all attendees. Special thanks to John Thorn for providing a copy of the booklet. Fowler was posthumously elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2022. The text below is republished here as it was printed in the original booklet.

By L. Robert Davids

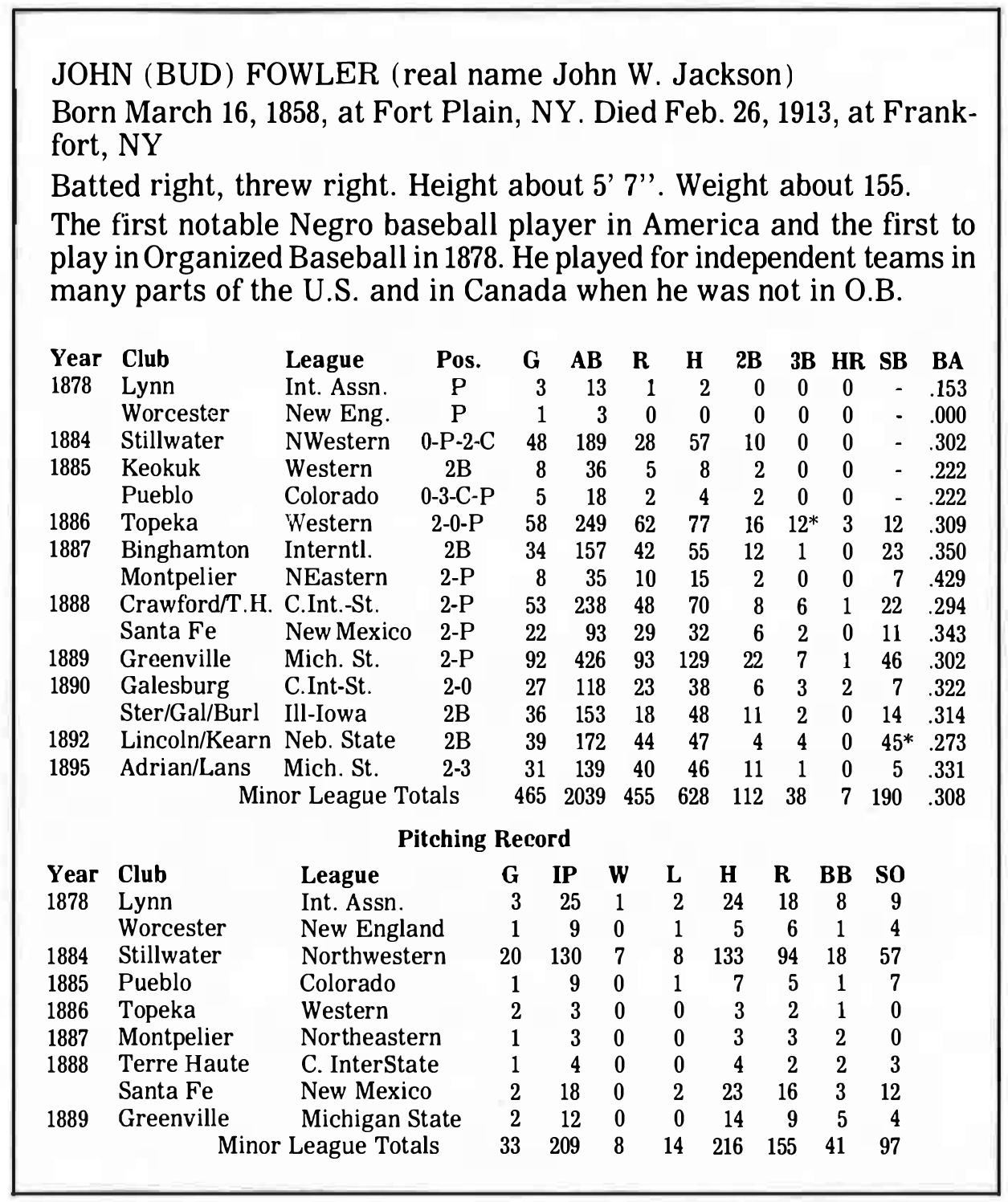

There were at least 70 blacks who played one or more games in organized minor league baseball from 1877, the start of the minor leagues, to the end of the 19th century when the colored curtain separated them from play with white teams. John W. Jackson, known in baseball as Bud Fowler, was the first by several years and the one who played the longest, ten seasons. He also was one of the best black players of that generation and thereby helped to provide a limited opportunity for other players of his race.

Research efforts to pull together the strands of Fowler’s life and put them into a coherent biographical sketch have not been totally successful. There are still several gaps. Census and family information indicate that he was born in Fort Plain, N.Y., on March 16, 1858, the son of John and Mary Lansing Jackson. The New York census of 1860 had the family in Cooperstown, N.Y., where the father was a barber. The same applies to 1870, at which time son John W. Jackson was listed as 13 and “attended school within the year.” It is good to know that a century before Satchel Paige was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, an adolescent black boy was already familiar with that upstate village and developing his ballplaying talents there.

No information is available on when our subject began his baseball career and when and where he took the name Fowler. It is known that the nickname “Bud” resulted from his inclination to call most others by that name. An 1895 article on Fowler, which included much misinformation, indicated that he first played professional ball with the Washington Mutuals in 1869 and a Newcastle, Pennsylvania, team in 1872. There is no confirmation for such entries, which would have been too early in life for him anyway.

The first documented mention of Fowler as a player was in April 1878 when he pitched for the Chelsea team in Massachusetts. On April 24 he pitched an exhibition game victory over the Boston Nationals of George Wright James O Rourke, and company, defeating Tommy Bond 2-1. When the Lynn Live Oaks of the International Association (the first Minor League temporarily lost their lead pitcher to illness, they acquired Fowler from Chelsea. The Boston Globe reported on May 18 that “Fowler, the young colored pitcher of the Chelseas,” held the Tecumsehs of London, Ontario, to only two hits and was leading 3-0 in the eighth inning when the Canadians became irked over an umpire’s-decision and left the field. Lynn won by forfeit. Fowler pitched two more league games in May, losing both. However, he did break the color line in organized professional baseball.

The first documented mention of Fowler as a player was in April 1878 when he pitched for the Chelsea team in Massachusetts. On April 24 he pitched an exhibition game victory over the Boston Nationals of George Wright James O Rourke, and company, defeating Tommy Bond 2-1. When the Lynn Live Oaks of the International Association (the first Minor League temporarily lost their lead pitcher to illness, they acquired Fowler from Chelsea. The Boston Globe reported on May 18 that “Fowler, the young colored pitcher of the Chelseas,” held the Tecumsehs of London, Ontario, to only two hits and was leading 3-0 in the eighth inning when the Canadians became irked over an umpire’s-decision and left the field. Lynn won by forfeit. Fowler pitched two more league games in May, losing both. However, he did break the color line in organized professional baseball.

Fowler was still in the Boston area in 1879, when he pitched for the Malden team in the Eastern Massachusetts League, a semipro circuit. He next pops up in 1881 in Guelph, Ontario. The local Maple Leafs had just signed him to pitch for them. However, his presence on the otherwise all-white club was vigorously opposed by one vocal member who led a revolt among his teammates. Fowler was dropped from the squad and wound up playing with the Petrolia Imperials, a lesser team some 100 miles southwest of Guelph. The Guelph Herald had this to say:

We regret that some members of the Map!e Leafs are ill-natured enough to object to the colored pitcher Fowler. He 1s one of the best pitchers on the continent of America and it would be greatly to the interest of the Maple Leaf team if he were re-instated …. He has forgotten more about baseball than the present team ever knew and he could teach them many points in the game … “

Fowler was still primarily a pitcher when he was signed by Stillwater, Minnesota, in 1884 to play in the 12-team Northwestern League. This was one of the leading minor leagues of that period with teams in such thriving cities as Grand Rapids, Fort Wayne, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and St. Paul. Stillwater did not have a very good team, losing its first 16 games. However, Fowler broke the spell with complete game victories on May 26, 28 29 and 31. He had several losses after that and started to play more at other’ positions. The St. Paul Dispatch provided these brief notes on his activities:

- June 15: When the Stillwater club won its first victory at Ft. Wayne, the colored pitcher for the Stillwater club was presented with a $10 bill and a suit of clothes for his strong contribution to the result.

- June 23: Fowler, the colored player for Stillwater was fined $10 for the wild throw he made in Saturday’s game.

- July 26: Fowler the colored catcher of the home team, was fined $50 just before the game and suspended for two weeks for refusing to catch Bradley.

There was no mention why Fowler would not catch Bradley, but it probably was because the pitcher would not take signals from a colored man and would throw whatever pitch he wanted {Moses Walker had that problem with Tony Mullane at Toledo in 1884): Anyway in spite of the lengthy suspension, Fowler was back in the lineup in four days. The reasons were probably based on necessity and related to a July 28 note that Stillwater’s lead pitcher ”J.F. Quinn, while in the act of delivering the ball, broke his right arm.”

Stillwater dropped out of the league in August, one of several clubs that disintegrated, for one reason or another, while Fowler was a team member. He was a good player, very versatile, and a fast runner. People came to see him play, but he was not docile when he was threatened. There probably were more confrontations than reported m the press of his day. A look at his playing record indicates that he didn’t stay very long with any one club.

Fowler played briefly with Keokuk, Iowa, in 1885 before that team collapsed. Fortunately he was included in a team photo, one of the few known illustrations of the 19th century star. His next stop was Pueblo in the Colorado League where he played five different positions in five games. The Denver Rocky Mountain News reported: “Fowler has two strong points: He is an excellent runner and proof against sunburn. He don’t tan worth a cent.”

In 1886 Fowler helped lead Topeka to the Western League pennant. Playing essentially the full season, he topped the circuit with 12 triples. Topeka had a Negro newspaper in 1886 but there was never a mention of the star ballplayer and practically no mention of sports activities. Baseball at that time apparently was not judged by the black press as a significant means of integration.

Returning to New York in 1887, Fowler probably achieved his highest level of play with Binghamton in the International League. While he had been the only black in the Western League in 1886, there were seven blacks in the International in 1887. The list included pitcher George Stovey, who won 34 games for Newark; Moses Walker, his catcher; and Frank Grant, the Buffalo second baseman, who led the league with 11 home runs. In a game report on May 8, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle said “the main interest was centered on two colored second basemen, Grant of the Buffalos and Fowler of the Binghamtons. …” The paper concluded that Fowler “played the best game and won much applause” as Binghamton triumphed 8-7.

Fowler and Grant both became targets while handling plays at second as opposition baserunners with high-flying spikes made a practice of taking them out of the play. It also was sometimes noted in the press that fielders played poorly behind a black pitcher to get him dropped from the team. This happened with William Renfro, Fowler’s pitching teammate with the Bingos. There were obvious racial problems on the Binghamton club, but they were not publicly apparent until the Chronicle reported on July 5 that “Fowler, Binghamton’s second baseman, has been released upon condition that he will not sign with any other International club. …” He had batted .350 in 34 games.

More information came out on August 8 when the Newark Daily Journal reported that “The players of the Binghamton Baseball Club were fined $50 each by the directors because six weeks ago they refused to go on the field unless Fowler, the colored second baseman, was removed. The Binghamton franchise folded later in August. By that time Fowler was playing with the Montpelier club in Vermont, where his tenure was short but where he was better received.

The Rutland Herald reported on August 24 that “Captain Fowler of the Montpeliers is a colored man and a first class ball-tosser in every respect. He played a brilliant game yesterday on second and made two of the four runs for his club … Fowler seemed to be the favorite with the spectators and was greeted with applause every time he stepped to the plate.” The next week the paper announced that Fowler had left for Laconia, N.H. There also were reports that-Fowler was to play with the Cuban Giants and the New York Gorhams, prominent all-black teams of that era, but this probably did not take place in 1887. For the most part, he seemed to cast his lot with white teams.

Baseball legends Monte Irvin (third from left) and Buck O’Neil (third from right) pose in front of Bud Fowler’s new grave marker on July 25, 1987, at a SABR dedication ceremony in Frankfort, New York.

It was back to the Middle West in 1888, where he played with Crawfordsville and Terre Haute in the Central Interstate League, primarily as a second baseman. That league broke up at the end of July and Fowler went to Santa Fe to play in the New Mexico League. After the close of that season, he went with the team on a tour of the southwest. A note in the Santa Fe New Mexican on November 24 said he was playing ball in San Bernardino, California.

The next year he spent the entire season with Greenville in the Michigan State League. The Grand Rapids Democrat had this commentary on June 16, 1889:

Fowler, the colored second baseman of the Greenvilles is a tricky player. When at the bat he turns his head occasionally and catches the sign made by the catcher to the pitcher and lays his plans accordingly. Meakim discovered the act yesterday and fooled him several times. It is said he has played in nearly every state in the Union coming here from Texas. He has a peculiarity or, perhaps a superstition, about striking at the first ball over the plate and always strikes at it whether over the plate or over his head.

In 1890 Fowler was back in the Central Interstate, playing for Galesburg. He had one of his best days there on May 2 when he collected six hits in seven trips and scored five runs as Galesburg walloped Peoria 31-6. However, his club disbanded on June 3 and Fowler shifted to the Illinois-Iowa League where be played initially with Sterling. Later he joined Galesburg, which had regrouped and changed leagues, and finally Burlington. He bad a very active day at Dubuque on July 28, collecting four hits and running wild on the bases. The Dubuque Daily Times was caused to say “And how some of them ran the bases, especially that man Fowler. Just think, five stolen bases off Jones in one game. As President Atherton said yesterday, if he had only been painted white he would be playing with the best of them.”

There was a sharp cutback in black players in the minors after the 1890 season. In 1891 the Cuban Giants played briefly as an all-black team in the Connecticut State League, and one black played for Jamestown in the New York-Penn League. That was it. Fowler spent most of the year playing for Findlay, Ohio, which had a good (mostly white) independent team. Findlay became a haven of sorts when he could not get into a regular league.

The Nebraska State League was organized in 1892 and several of the teams took risks by signing players from the defunct Lincoln Giants, an all-black team located in the Nebraska capital in 1890. Fowler joined the Lincoln entry in the State League along with William Castone, who had pitched for the Giants. Three other clubs had one or more former Giants. (One non-black making his pro debut, with Hastings, was future Hall of Fame outfielder/manager Fred Clarke.) Lincoln ran into almost immediate financial problems and the team shifted to Kearney in mid-state.

Otherwise, play moved along fairly smoothly until a game between Kearney and Grand Island on May 29, 1892. The problem occurred when Joe Rourke, player-manager of Grand Island, went from first to second on a ground ball to Fowler. As described by the Grand Island Independent, “The latter (Fowler), instead of touching second, pounded both fists and the ball into Rourke — where he lives — and knocked the wind out of him. Rourke’s temper took a flight and then it looked like a coroner’s inquest would follow. It was a disgusting exhibition all around. Both men are perhaps equally to blame.”

On June 1 there was a vague reference in the Nebraska State Journal Lincoln to the “colored problem,” adding that While President Brewer and Secretary Rohrer are opposed to colored players they are inclined to see them have fair play as long as they remain in the league.” This situation plus financial problems, caused a gradual disintegration of the league. Teams started dropping out and when only two remained on July 12 that was the end. Some of the players went on tour, Fowler, the leading base stealer, among them.

Negro Leagues veteran Buck O’Neil (at podium) speaks at a dedication ceremony for Bud Fowler’s new grave marker on July 25, 1987, in Frankfort, New York. (Photo: FultonHistory.com)

It was back to Findlay, Ohio, in 1893 and 1894. He would play as long as he could and in the off-season would work as a barber, which was his father’s trade. With no apparent openings in white leagues, Fowler contemplated organizing his own all-black team. Support for such an undertaking was Jacking in Findlay, but on his visits with the team to Adrian, Michigan, which also had an independent club, he was able to interest parties there in providing the financial support for his proposed midwestern counterbalance to the Cuban Giants. The sponsorship he desired came from the Page Woven Wire Fence Company of Adrian. The Page Fence Giants were officially organized (on paper) on September 20, 1894, and Fowler immediately set about recruiting a first class team. While serving as a barber in Adrian during the off-season, he promoted the team to the local populace.

In the spring of 1895, the Page Fence Giants, which included Fowler as playing manager and shortstop Grant Johnson his teammate at Findlay in 1894, as team captain, played two exhibition games in Cincinnati against the Reds. The Giants lost on both days, but then the Reds fielded such well known major leaguers as Arlie Latham Biddy McPhee, Dummy Hoy and player-manager Buck Ewing. While there, Fowler had a lengthy promotional interview with the Cincinnati Enquirer on April 12 which stated in part:

It was a great game. Bud Fowler, the veteran, has got together a great team of players. They will win more than they will lose … Fowler has been playing baseball for the last 26 years, and he is yet as spry and as fast in his actions as any man on the team. He has no charley horses or stiff joints, but can bend over and get up a grounder like a young blood … Altogether he is a wonder. Fowler attributes his remarkable condition to the fact that he has always taken care of himself. Wine, women and song have played a very little part in the life of this veteran of the diamond. Go out and see him play second base this afternoon.

The Giants clad in elaborate Page Fence uniforms and riding in their own railroad car, had a successful season while touring in six midwestern states. They won 118 games and lost 36 against a wide range of minor league and independent teams. Ironically Fowler left the team, his own creation on July 15, 1895, to play in the Michigan State League. He may have enjoyed more the individual attention he received playing on mostly white teams and this turned out to be his last opportunity to play in the minors. It was his tenth year as an official minor leaguer, four more than achieved by Moses Walker, Frank Grant and George Stovey.

There was not much recorded information on Fowler after the 1895 season. He continued to play with the Findlay team, at least until July 1899 when this item appeared in The Sporting News: “The white members of the Findlay ball club have drawn the color line and have demanded of Dr. Drake, their backer, that Bud Fowler, colored, be ousted from the team. They will quit if their demand is not heeded.”

He also was engaged in some Negro barnstorming activities and some separate ventures. On May 29, 1898 he was in Newark, N.J., to play second base for the Cuban Giants. On May 24, 1900, he was in Columbus, Ohio, with the Black Tourists, a team which he had organized to play against various black or white teams. The Black Tourists defeated the local Lancaster, Ohio, team 13-4, with Fowler playing his usual second base position. There was a photo of the team in the Columbus paper. In May 1901 he was in Pittsburgh with a team he organized called the Smoky City Giants.

As his playing days waned, Fowler concentrated more on managing and organizing black teams. His philosophy was summed up in an article in the Cincinnati Enquirer on November 10, 1904.

Bud Fowler, patriarch among the black sons of swat, is in Redland after a season of success in Missouri, where he managed the Kansas City Stars, a team of colored ball players. “Some of these days,” said the veteran, “a few people with nerve enough to take the chance will form a colored league of about eight cities and pull off a barrel of money. I know the field is there and I’d like to see Cincinnati in such an organization. I expect to remain here and have a learn of black boys to play in Ohio and Indiana cities next season. This was the greatest year in baseball’s history for the independent clubs. My Kansas City Stars did splendidly in a tour of Kansas and Nebraska.”

Fowler, who was spending the winter in Cincinnati as a “knight of the razor,” volunteered the information that “I haven’t pitched a ball for three years. The old whip went back on me and I’ve gone to the bench to stay.”

A new generation of baseball fans was reminded of Fowler’s contribution as player and manager when Sol White’s History of Colored Baseball was published in 1907. White, a contemporary player and team organizer, called Fowler “the celebrated promoter of colored ball clubs and the sage of baseball.”

The New York Age, a black newspaper, headlined an article in its February 25, 1909, edition: “Bud Fowler Ill and In Want.” The first paragraph summed up the situation as follows:

John Fowler, familiarly known as “Bud,” who was a member of the Binghamton team of the International Association when that organization was part and parcel of the “big show” … and known as a colored baseball star through the country, is ill at the home of his sister (Harriet) at Frankfort, N.Y., and said to be in destitute circumstances. Sol White, for years captain of the Philadelphia Giants, and F.D. Ellis, a Brooklyn newspaper man, are arranging a benefit game for him, which will be played at Meyerrose Park, Ridgewood (N.J.) during April. Many of the colored stars of the game will be present. It had been supposed that he was a victim of consumption, but an X-ray examination reveals the fact that his sickness is the result of an injury received at Indianapolis seven years ago while sliding to second base … Physicians say that an operation will perhaps make the old boy well again.”

On April 22 the Age said the game had been postponed because of difficulty in getting the players together. On October 7, 1909, the Age again announced plans for a benefit game for Fowler on October 17. The date passed without any further mention so it is assumed that no benefit took place.

There is no other mention of Fowler until an obituary, recently uncovered, appeared in the Frankfort (N.Y.) Evening Telegram of March 1, 1913. It stated in part:

The death of John W. Jackson, which occurred yesterday at the home of his sister … he was one of the most famous ball players of the country and one who always took great pride in his baseball record … In baseball circles he was known as “Bud Fowler.” … Some six or seven years ago he came to this village and undertook the organization of a championship team of colored players from all parts of the country but the financial backing, which he was counting on, did not come up to his expectations and he gave up the project. Most of the time, for the past few years, he made his home in New York and he was taken ill there a few weeks ago. He then came to the home of his sister, here, where he was tenderly cared for, but he failed steadily …. The funeral was held this afternoon from the home of Mr. and Mrs. Odom.

Fowler’s death certificate indicated that he died of pernicious anemia on February 26, 1913 and was buried in the Frankfort cemetery. His age was given as 54 years, 11 months, and 10 days. So ended the extraordinary and still not fully explained saga of Bud Fowler/John Jackson. Although all the facts are not available, enough is known of his life and exploits to show that he fought the odds and made a limited but historically important impact on 19th century baseball.

Note: Statistics were the best available at the time of publication in 1987.

THE CONTRIBUTION OF BLACK PLAYERS IN THE 19TH CENTURY

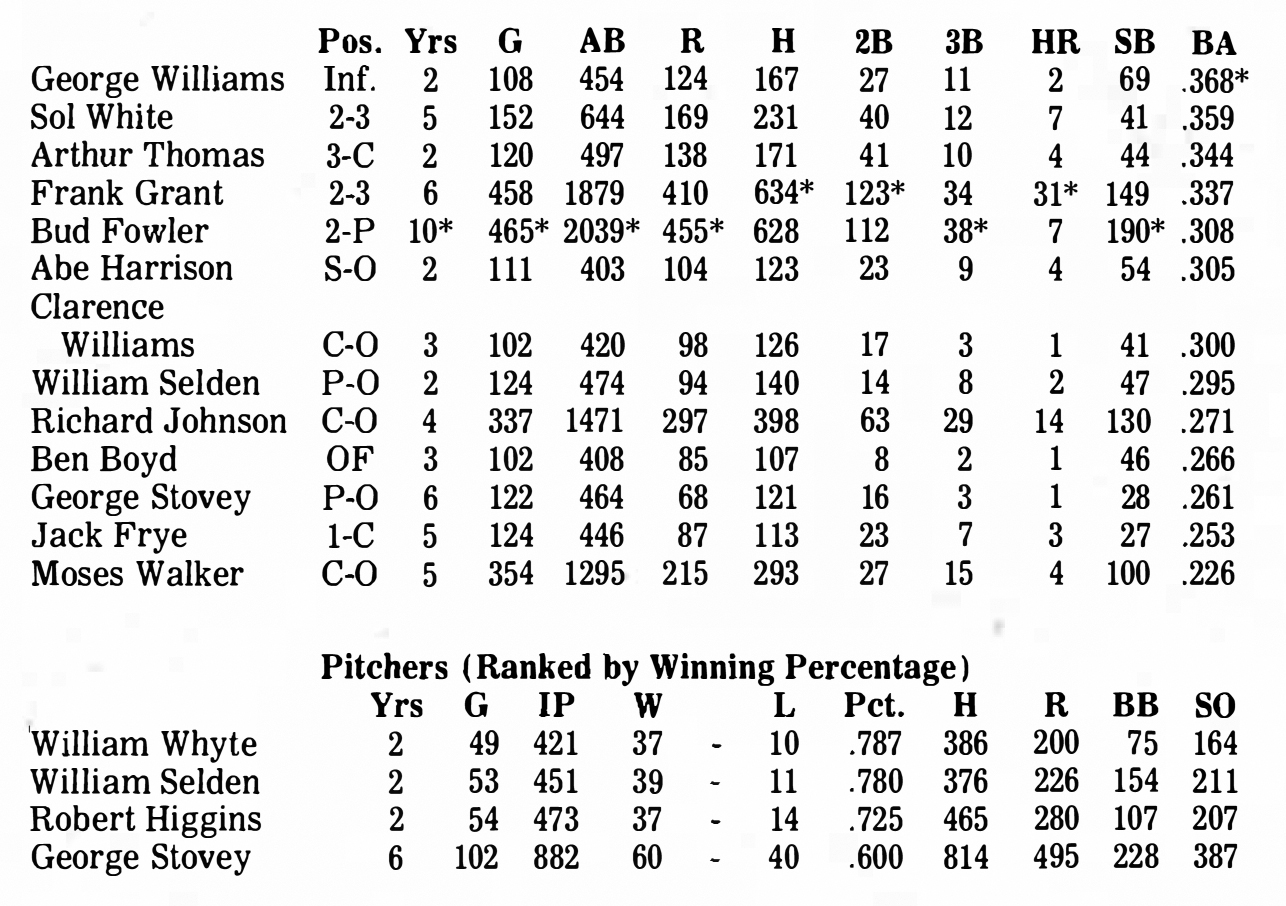

About one-half of the 70 blacks who played in the minors in the 19th century played only on all-black teams. This was in sharp contrast to the case of Bud Fowler who spent all of his ten O.B. seasons with white teams. An all-black team playing in an otherwise white league was an interesting experiment, and did stimulate attendance and result in keen competition, but ultimately it failed.

The concept was initiated in the Middle States League in 1889 when the Cuban Giants, considered the best black team in the nation at that time, opened the season as the entry for Trenton N.J. Playing with such stars as Frank Grant, brothers Clarence and George Williams, Jack Frye, and pitchers William Selden and William Whyte, the club compiled a spectacular 55-17 record. Nevertheless, the League awarded the pennant to Harrisburg, which had a similar percentage but played more games.

The New York Gorhams, another black team, joined the loosely regulated league in late June and stayed until mid-August when the club was expelled for missing scheduled dates. Sol White was the star of that team, which operated out of Philadelphia most of the time. Pitcher George Stovey was in the line-ups of both the Giants and Gorhams, a reflection of the loose organization of that time.

In 1890 the Cuban Giants represented the York, Pa., team in the renamed Eastern Interstate League. They again played very well even though two of their players — Frank Grant and Clarence Williams — joined their chief rivals in Harrisburg after the club pulled up stakes at midseason and joined the Eastern Association. The Eastern Interstate folded shortly thereafter.

Grant and Williams returned to the Cuban Giants in 1891 and the club, which also secured Sol White, represented Ansonia in the Connecticut State League. However, the weather was bad, attendance was spotty, and the Giants skipped several dates to play independent teams. The league disbanded in early June.

In 1898, with blacks practically nonexistent in the minors, a final experiment was tried when the Acme Colored Giants played as the entry for Celeron, N. Y., in the Oil and Iron League. It was primarily poor play which caused their demise in mid-season, at which time the club had only eight wins and 41 defeats. That was the end of all-black teams in the minors — until 1952 when Chet Brewer managed such a club in the Southwest International League. That also was a one-year experiment.

The tenure of blacks on white minor league teams, as emphasized by the career of Bud Fowler, was usually very short. Frank Grant spent three consecutive seasons, 1886-1888, with Buffalo in the International League. Bert Jones was a pitcher-outfielder with the lower classification Atchison team in the Kansas State League in 1896-97-98, until he was forced out in the latter season. There were five other players who spent parts of two seasons with the same club. Otherwise it was one season or a fraction thereof.

Even with those restrictions several black players were able to put together some notable game, season, and even career records in the minors, as shown below.

- George Stovey, pitching for Jersey City in the International League on August 28, 1886, shut out Newark 1-0, giving up only two hits and fanning 15. Newark acquired him in 1887 and he won 34 games that season.

- On May 15, 1889, Abe Harrison, shortstop for Trenton ( Cuban Giants), hit for the cycle (home run, triple, double, and single) and added a second single.

- Pitcher George Wilson won 29 games and lost only four for Adrian in the Michigan State League in 1895. That was his only season in O.B.

- In 1890 George Williams of York led the Eastern Interstate League in batting with a .391 average. Teammate Arthur Thomas led the circuit with 26 doubles and 10 triples.

- Frank Grant led the International League in home runs with 11 for Buffalo in 1887. It is possible that he was a switch hitter as it is recorded that with Trenton on August 29, 1889, he “batted a home run with his left hand.”

- Trenton had a spectacular pitching duo in 1889 with William Whyte racking up a 26-5 won-lost record while William Selden was 23-6.

- Richard Johnson, primarily a catcher with Springfield in the Central Interstate League in 1889, hit 14 triples, stole 45 bases, and scored 100 runs in 100 games.

- Pitcher Bob Higgins was 20-7 with Syracuse in 1887. On August 10, in a rare confrontation of black hurlers, he defeated southpaw George Stovey of Newark 2-0. Moses Walker was Stovey’s catcher with Newark that year. In 1888 he caught Higgins at Syracuse.

Here are the minor league career batting records of some of the best black players of the 19th century. They are ranked by batting average.

Note: Statistics were the best available at the time of publication in 1987.

The Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) thanks the following persons who provided cash gifts and/or special services to the Bud Fowler memorial project, including this booklet:

- Bob Carroll

- Dick Clark

- Dean Coughenour

- Bob Davids

- Carolyn Gillis

- Tom Hufford

- Lloyd Johnson

- Jerry Malloy

- Raymond Nemec

- John Pardon

- Jody Peter

- Robert Peterson

- Betsy Prockish

- David Skinner

- Gene Sunnen

- George Tillapaugh

- Joe Vellano

- Russell Wilhoit

- Edith Williams

- Merle Wise

- Craig Wright

Special thanks go to Richard E. Clark of Oak View Cemetery in Frankfort, NY, where Bud Fowler lies buried in an unmarked grave. With his cooperation a memorial stone, to be erected by SABR, will be dedicated at the site on July 25, 1987.

This booklet was researched and written by Bob Davids, who had the assistance of several SABR members. It was prepared for publication by the staff of Ag Press in Manhattan, Kansas. Information about SABR, a non-profit organization established in 1971, can be obtained from the Society’s executive director, Lloyd Johnson c/o SABR, P.O. Box 10033, Kansas City, MO 64111.