Don’t Believe the Dope: Few Saw Black Sox Scandal Coming

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee’s June 2019 newsletter.

By Kevin P. Braig

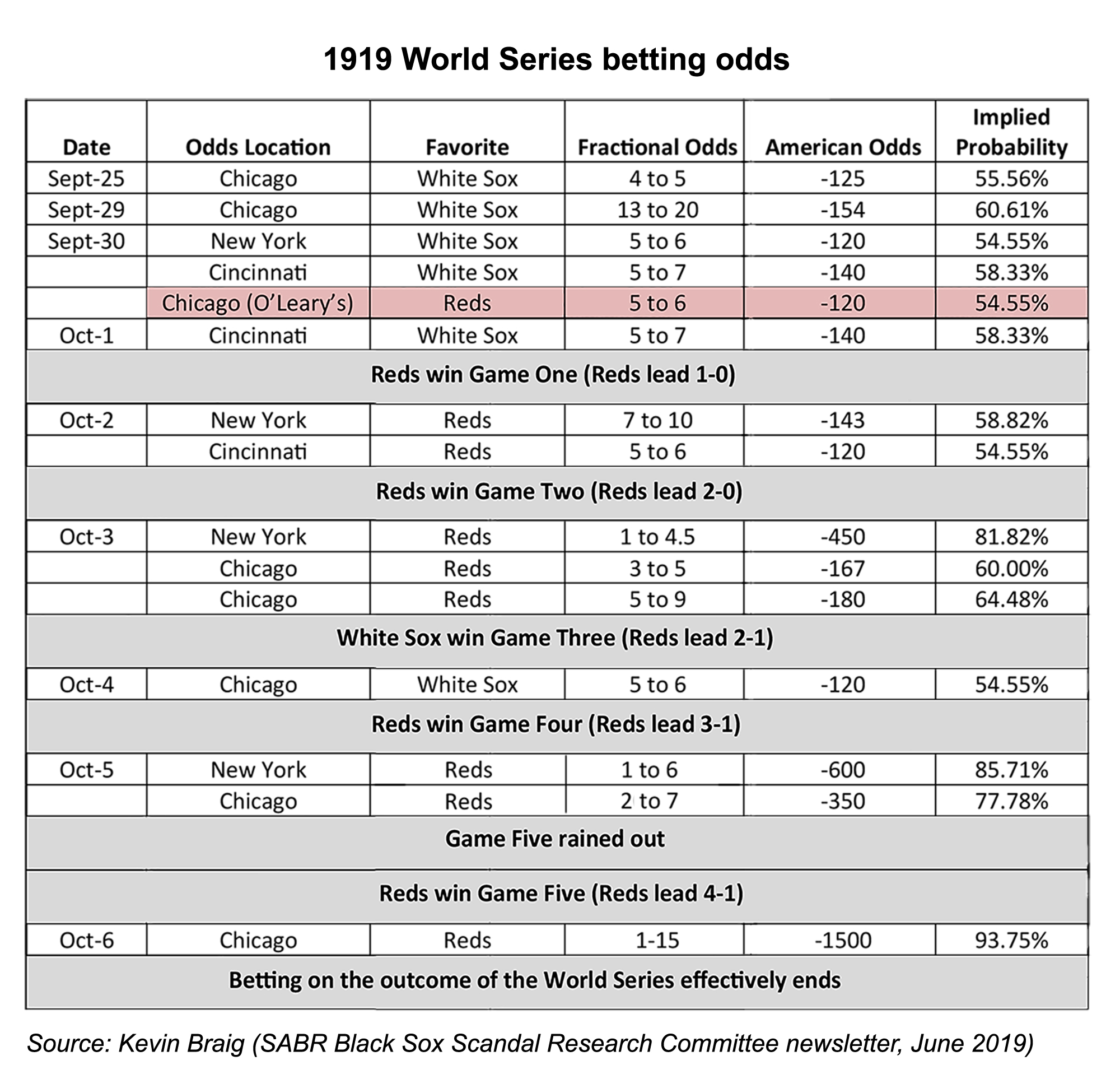

Like many other aspects of the 1919 World Series, reports relating to odds-making and betting on the outcome of the Series are contradictory. On one hand, some accounts claimed the action was hot and the odds shifted dramatically toward Cincinnati as “hundreds believed that the thing was fixed” before Game One.1 On the other hand, almost all contemporaneous reports describe sluggish handle and typical odds movement from the day after the Chicago White Sox clinched the American League pennant to the day the Cincinnati Reds clinched the Series with a 10-5 win in Game Eight.

Like many other aspects of the 1919 World Series, reports relating to odds-making and betting on the outcome of the Series are contradictory. On one hand, some accounts claimed the action was hot and the odds shifted dramatically toward Cincinnati as “hundreds believed that the thing was fixed” before Game One.1 On the other hand, almost all contemporaneous reports describe sluggish handle and typical odds movement from the day after the Chicago White Sox clinched the American League pennant to the day the Cincinnati Reds clinched the Series with a 10-5 win in Game Eight.

The media’s coverage of the 1919 World Series presents a textbook example of the “golden age of media coverage of sports betting.” Reporters covered the betting action on the Series with every bit as much — and perhaps more — detail as David Purdum of ESPN or Darren Rovell of the Action Network do today.

Betting on sports was less centralized in 1919 than it is today and, of course, reporters did not enjoy the advantages that digital network communications provide today. Still, a reasonably representative data set supplemented by anecdotal evidence is available to be analyzed.

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

There is little to no reason to think the fundamental economics of odds-making in the early 20th century was radically different from the fundamental economics of odds-making in the early 21st century. For this paper, the fundamental economics of odds-making are contained in economist Koleman Strumpf’s 2003 paper Illegal Sports Bookmakers.2 In his paper, Professor Strumpf found that:

- Economic self-interest plays a central role in shaping the industrial organizations of bookmakers.

- Bookmakers are not risk-averse or perfectly diversified, but rather gamble and take positions on games.

- Bookmakers have some limited market power and use that power to price discriminate by setting adverse odds for hometown teams, the sentimental favorites.

This paper will focus on odds-making and betting on 1919 World Series in Cincinnati, Chicago, and New York. The focus on Cincinnati and Chicago is justified by Professor Strumpf’s findings that bookmakers in those cities should have been able to charge local fans higher prices in the form of worse odds on the Reds and White Sox, the sentimental favorites. The focus on New York is justified by the fact that much of the planning and preparation to fix the 1919 World Series occurred in New York.

The analysis in this paper includes examination of the following aspects of the 1919 World Series odds-making and betting markets:

- Comparison of the odds that the favored White Sox would win the 1919 World Series to the odds on other World Series favorites, particularly favorites since 1985;

- Key injury reports, Game One starting pitcher speculation, and a key expert report from former New York Giants’ star pitcher-turned-analyst, Christy Mathewson;

- Opening odds and betting and changes in the odds and betting as the 1919 World Series played out;

- Betting practices of celebrity/quasi-professional bettors Nick “The Greek” Dandolos, Abe Attell, and George Cohan; and discussion of reasons to doubt Abe Attell ever stood atop a chair in the lobby of the Sinton Hotel in Cincinnati clutching $1,000 bills and frenetically booking bets on the White Sox; and

- Odds-making and betting at two of the most renowned and respected betting establishments in the country: Jack Doyle’s pool room in Times Square in New York and James O’Leary’s handbook in the Stockyards District on the South Side of Chicago.

Based on the analysis contained herein, this paper concludes that with one important exception — odds-making and betting at James O’Leary’s handbook — odds-making and betting on the 1919 World Series looked pretty much like one would expect it to look if the Series had been played completely on the level.

It does not appear that other than at O’Leary’s handbook the odds changed much from the open until after the White Sox lost Game One and did not change dramatically until after Chicago also lost Game Two. Further, it does not appear that “hundreds of people” knew the 1919 World Series was fixed before the first pitch of Game One was thrown or that any significant number of people had pre-Series knowledge of The Fix and acted to bet Cincinnati based on such knowledge.

Make no mistake: The 1919 World Series was fixed. A few people outside of The Fix operators really knew or were actionably confident that “The Fix was in” and, undoubtedly, a significant number more were suspicious.

But no contemporaneous odds-making or betting evidence has been located that would support Hugh Fullerton’s October 3, 1920 claim that “so openly and notoriously was the attempted prostitution of the world series carried out that before the first ball was pitched hundreds believed that gamblers at last had succeeded in corrupting the sport which had been considered incorruptible.”3

James O’Leary’s saloon and gambling hall at 4183 South Halsted Street in Chicago was one of the most renowned betting establishments in the country. It was also where the betting market during the 1919 World Series was at its most peculiar. (Photo: Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1935)

Comparison to Other World Series Favorites

A good place to begin analyzing the odds-making and betting on the 1919 World Series is by comparing the odds on the favored White Sox to the odds on other World Series favorites. On October 3, 1920 — after Chicago pitcher Eddie Cicotte confessed his involvement in The Fix to the Cook County Grand Jury — Hugh Fullerton wrote:

Never before in a world’s series (with one exception) had any team been as greatly outclassed as the Reds were in that series…. The odds quoted by the gamblers three days before the Series opened [September 28] were at two and a half to one [-250, 71.43% implied probability] that Chicago would win.4

Fullerton’s facts are plainly incorrect. The White Sox clinched the American League pennant on September 24, 1919. The next day, the Chicago Tribune reported Chicago’s bookmakers had installed the White Sox as a 4 to 5 favorite to win the World Series [-125, 55.56%].5 According to a September 29 column by Harvey T. Woodruff, that figure attracted an $8,000 bet [$121,809.94 in today’s dollars] on the Reds from Milwaukee.6 Still, the odds moved in Chicago’s direction to 13 to 20 [-154, 60.61%].7

No reports were found in Chicago, Cincinnati, or New York newspapers of the pre-Game One odds favoring the White Sox that topped the 61 percent implied probability of victory in the Series,8 much less approaching Fullerton’s implied probability that Chicago was 71.43% likely to capture the Series.

Further, one only has to look back to the 1916 World Series between the Boston Red Sox — led by star pitcher Babe Ruth — and the Brooklyn Robins to find a bigger opening favorite than the 1919 White Sox. In 1916, Ruth’s Red Sox opened as 5 to 7 favorites [-140, 58.33%] at Jack Doyle’s pool room in Times Square in New York City and within an hour after the Robins were declared National League champions, $3,500 was placed on deposit at Doyle’s to be bet against $2,500 that the Red Sox would win. As The (New York) Evening World observed, “The money at Doyle’s is the only real coin that has been shown, and the odds fixed there are probably correct.”9

Comparisons to the odds on favorites in more recent World Series reveal that the opening odds on the White Sox would tie for the fourth weakest odds on a World Series favorite since 1985 (See Table 1.10) In other words, since 1985, odds-makers thought more highly of the World Series favorite than odds-makers thought of the White Sox in 29 of 34 World Series matchups (85.29%).

Table 1: World Series betting odds

(Click image to enlarge)

These figures demonstrate that while Hugh Fullerton strongly thought Chicago was nearly a lock to win the 1919 World Series, Chicago’s odds-makers and bettors had much more respect for Cincinnati and expected the matchup to be one that was fairly even and would be closely contested.

Key Injury Reports

It is well-established that key injuries, starting pitcher matchups and the views of key experts can move betting odds in baseball. The 1919 World Series was no exception. Yet, prior discussion of odds movement and betting on the Series has heretofore dismissed or minimized these factors.

In Eight Men Out, Eliot Asinof relied on an October 1, 1919, report in the New York Times that odds in New York shifted toward the Reds on September 30 as evidence The Fix had become “actionable information” in the betting markets.11 But Asinof dismissed the first sentence of the report which clearly identified the reason for the move: “The report to the effect that Eddie Cicotte has a sore arm, which was current in New York yesterday, had a material effect on the world series betting.”12

Rather than accept at face value that doubts about Cicotte’s pitching fitness and form had emerged, Asinof drew the following conclusions: “The smart money had abandoned the White Sox. The excuse given for — or so it was rumored — was a report that Cicotte’s arm was sore. Gamblers knew this was nothing more than a cover-up for the fix.”

There are numerous alternate, reasonable bases to reject Asinof’s conclusion that information, whether accurate or inaccurate, about Cicotte’s fitness was a “cover-up for the fix,” including:

- No first-hand source with direct, personal knowledge of both The Fix and the origin of the information about Cicotte’s fitness has been located that would corroborate the conclusion that the health status of Cicotte’s arm was a “cover-up.”

- As Professor Strumpf has stated, gamblers are economically self-interested and creating a “cover up” that weakened the odds on Chicago — such as Cicotte was suffering from a sore arm — would have conflicted with the economic self-interest of Reds’ backers — including those with knowledge of The Fix, who would make more money if the White Sox odds strengthened.

- On September 28, the most popular and respected pitching expert in New York history, Christy Mathewson, wrote in the New York Times that bettors should beware putting too much faith in Cicotte and that he believed the Reds hitters would enjoy success against Cicotte.13

As is discussed below, several reports relating to the odds the morning of Game One indicate money did not “abandon” Chicago on September 30 or the morning of October 1.

As is also discussed below, one of the places in New York where the odds moved toward Cincinnati was Jack Doyle’s Times Square pool hall and, if other gamblers had knowledge of The Fix, it is likely that Doyle would have had that knowledge too. Finally, Cicotte was hit fairly hard in his last two appearances during the 1919 regular season, which may have been an alternate basis for bettors to believe Cicotte was not fit or in top form.14

Health and pitching uncertainty also swirled around the Reds during the days before Game One. On September 30, Frederick G. Lieb reported in the New York Herald that “Cincinnati fandom received quite a shock to-day when Heinie Groh, the little captain and star third baseman of the Reds, confessed that the injury which kept him out of the Redland lineup for the last month of the season wasn’t a bruised finger, as was announced by the club, but that the finger actually was broken.”15 However, the report also confirmed that Groh would in fact play in the Series as he had in the last two regular-season games after missing a month of action.

Until at least the night before Game One, most scribes believed manager Pat Moran would start 21-game winner Slim Sallee against Cicotte. However, on September 30, Moran and White Sox skipper Kid Gleason “established somewhat of a world series precedent” by announcing the day before Game One that Dutch Ruether and Cicotte would oppose each other in Game One.16

Until at least the night before Game One, most scribes believed manager Pat Moran would start 21-game winner Slim Sallee against Cicotte. However, on September 30, Moran and White Sox skipper Kid Gleason “established somewhat of a world series precedent” by announcing the day before Game One that Dutch Ruether and Cicotte would oppose each other in Game One.16

Without any first-hand, corroborating evidence that anyone in New York outside a small band of fixers had actionable information about The Fix and with publicly available information that the White Sox’s star pitcher possibly was less than 100% fit and an esteemed ex-New York pitching star believed Chicago was relying too heavily on its star hurler (even if completely healthy), Asinof’s contention that movement of the odds in New York toward Cincinnati is best characterized as evidence of the author’s “hindsight bias,” not evidence The Fix had attained the level of actionable information in the New York betting market.

A more reasonable analysis of all the information that was available in 1919 is that the odds in New York moved slightly toward Cincinnati on September 30 as:

- Bettors absorbed the uncertain information about Cicotte’s fitness and Mathewson’s views on Chicago’s over-dependence on Cicotte; and

- Bettors became more certain of the identity of the Reds’ starting pitcher and that Groh’s injured finger might inhibit his performance, but not keep him out of the lineup entirely.17

Opening Odds and Changes in Odds

The work week of the 1919 World Series began on Monday, September 29 in Cincinnati. According to the Reds’ beat writer, Jack Ryder, there was heavy betting that day. It just was not betting on baseball … or even in Cincinnati. Ryder reported:

It was a big afternoon at the Latonia track, for most of the baseball bugs, including a large delegation of the Red players, dashed over the river to glance at the ponies. The track officials reported that it was one of the biggest Monday crowds they have ever entertained and that the mutual machines did an unusually heavy business.18

Back in the city, according to Ryder and others, there was “very little betting” on the World Series before Game One.19 But that was not due to a lack of money backing the White Sox. On the same day the Latonia track was enjoying record handle, Harvey T. Woodruff reported in the Chicago Tribune the Chicago “board of trade has $25,000 [$365,871.15 in today’s dollars] seeking even money, which will be taken to Redland and offered at 5 to 4 [-125, 55.56%] if even money cannot be secured.”20

One would think the fixers would have pounced on the Chicago Board of Trade’s $25,000 the moment it hit the city limits. To the contrary, on October 1, not only did the Chicago Tribune not report anyone willing to cover the Board of Trade’s proposed big bet, but it also reported that “big money” from New York seeking action on the White Sox was being ignored at stronger odds, stating:

It has been learned that a big sum of money from New York has been here several days and offered at odds of 7 to 5 on the White Sox [-140, 58.33%], and only a little of it has been covered by the enthusiastic Cincinnati fans.

The New York money also was to be placed at 6 to 5 [-120, 54.55%] that Chicago wins the first game, and the commissioner in charge of the bank roll found few takers. It looks as if the odds might go as high as 2 to 1 [-200, 66.67%] in favor of the Sox before the first game tomorrow.21

Table 2: Analysis of 1919 World Series betting odds

(Click image to enlarge)

As shown in Table 2, in Cincinnati, according to the Chicago Tribune, on Tuesday, September 30 — the day before Game One — the White Sox “still rule[d] a heavy favorite at odds from 7 to 5 to 3 to 2.” On October 1, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported:

There has been very little betting on the series to date. White Sox money is prevalent, but nearly all of it is offered at evens, or six to five at best. There are many thousands of dollars in town to bet on the White Sox at even money, but no takers. The Reds supporters, while expressing great confidence in their team, are demanding seven and eight to five, and this is a little more than Sox speculators care to offer.

Not a single wager of any considerable size had even registered up to a late hour last evening. There may be some action today, but there will have to be mutual concessions. All day yesterday Sox money was going begging all over town with no one to cover it at even money. The White Sox continue favorites in the dope and betting talk. It is mostly talk. Owing to the weak purchasing power of a dollar these days money speaks in whispers.22

On October 2, the Chicago Tribune reported, “With the arrival of out of town visitors, betting on the series became brisker and more Cincinnati money was in evidence, but odds were demanded.” Several substantial wagers were placed at 6 to 5 that the White Sox would win the first game and 7 to 5 [-140, 58.33%] the Sox would win the Series.”23

The New York Times also reported the odds in Cincinnati the morning of Game One still had the White Sox 5 to 7 favorites [-140, 58.33%]24 and that “[b]ets of $33,000 [$502,466.00 in today’s dollars] were lost on Wednesday’s game by the Woodland Bards, the 234 ‘sweet singers’ from Chicago, who came here in an effort to root the White Sox to victory.”25

On October 3, the Boston Globe reported Chicago as an even bigger 5 to 8 favorite [-160, 61.54%] in Cincinnati the morning of Game One.26 These real-time, on-the-scene reports flatly contradict accounts that the odds moved dramatically in Cincinnati toward the Reds the morning of Game One.

Even after Cincinnati trounced Chicago, 9-1, in Game One, odds reports on the ultimate outcome of the World Series were conflicting. In New York, according to the Chicago Tribune, Cincinnati moved to a 7 to 10 favorite.27 The Boston Globe reported the Reds had transitioned to 5 to 6 favorites in Cincinnati.28 But the Chicago Tribune reported Reds’ supporters still were asking even money on the outcome of the Series. The New York Times added additional detail to the change in the odds, reporting:

There had been up to this morning very little Cincinnati money in evidence. It appears, however, that it was not lack of confidence in the team and its ability to mow down the White Sox which kept the local partisans from letting their money talk as it was a canny desire to get better odds by withholding their wagers. At any rate when followers of the White Sox began today in the after breakfast hours to offer odds hovering around 7 to 5, the concealed backers of the Reds made their appearance, and considerable money was bet at these odds or thereabouts.

…

[As a result of the Reds’ Game One victory,] the complexion of the betting has entirely changed. Instead of demanding 7 to 5, or even 8 to 5, as was the case last night and this morning, some Cincinnati money has been placed at evens tonight. It has appeared, in spots, but not in bulk, at more preferential rates for the White Sox backers, some of whom have received odds of 11 to 10, and occasionally 6 to 5, in small wagers placed at about the dinner hour.29

After Cincinnati won Game Two, 4-2, and jumped to a 2-game lead in the Series, the odds, finally, dramatically moved toward the Reds.30 In a story titled “Chicago ‘Wise Ones’ Are Putting Their Money on the Redlegs,” the Cincinnati Enquirer reported on October 3 that Cincinnati had become a solid 3 to 5 favorite [-166.67, 60%]31 and reported on October 4 that the odds strengthened further to 5 to 9 [-180, 64.48%] before Game Three.32

White Sox backers in New York had become even more skeptical, refusing to wager on Chicago at inflated odds as long as 1 to 4.5 [-450, 81.82%] according to a New York Times report on October 3.33

According to Bozeman Bulger of The Evening World in New York, the White Sox’s 3-0 win behind pitcher Dickey Kerr in Game Three temporarily restored the faith of Chicago’s backers. Bulger wrote:

With the count two to one in favor of the Reds so far, the betting commissioners are badly confused in fixing the betting odds. In a nine-game series it is quite different from a seven game affair. The moral effect is telling. Cincinnatians are loath to step out. And with the White Sox rooters overanxious several big bets were placed this morning at 6-5 [-120, 54.55%], despite the fact the Reds still have the edge.34

But that faith was short-lived. After Cincinnati’s Jimmy Ring won a 2-0 pitcher’s duel against Eddie Cicotte in Game Four to put the Reds up 3-1 in the World Series, the Reds skyrocketed to 1 to 6 [-600, 85.71%] favorites in New York,35 although Cincinnati remained a somewhat more modest 2 to 7 [-350, 77.78%] favorite in Chicago.36

Reds manager Pat Moran could not contain himself, saying, “It was amusing to me when the White Sox people were offering big odds that they would beat us. How are they going to beat pitching like Ring displayed yesterday? Not a chance in the world.”37

When Cincinnati’s Hod Eller again blanked the Sox, 5-0, in Game Five and the Reds took a commanding 4-1 lead in the World Series, the media proclaimed betting on the outcome of the Series over. Under the headline, “Series Betting Ends,” the New York Times observed, “The betting in Chicago on the world’s series has become almost entirely a matter of one game at a time. There is talk tonight of a few wagers at long odds, two of them being at fifteen to one [-1500, 93.75%], on the ultimate result, but the sums were comparatively small.”38

In general, there is little about the odds-making or betting on the 1919 World Series that suggests a significant number of bettors possessed actionable knowledge that “The Fix was in.” Almost everywhere, the White Sox opened up as somewhat weak favorites and — after the odds bounced around a little in response to pre-Game One uncertain information stemming from injury reports and Christy Mathewson’s expert analysis — went off the morning of Game One as favorites.

After Cincinnati seized early control of the Series, White Sox backers began to beat a retreat and completely abandoned Chicago after the Reds took an insurmountable 4-1 lead in the Series. At the 10,000-foot level, the action on the World Series looks almost perfectly normal.

However, because there is no dispute the 1919 World Series was fixed, a closer, more personal examination of the some of the bettors and odds-makers is warranted. When a micro-examination of celebrity/quasi-professional bettors and leading odds-makers is undertaken, a clear anomaly is revealed. But this anomaly did not arise in Cincinnati as Eliot Asinof, Hugh Fullerton, and James Crusinberry would have you believe. Nor did the anomaly arise in New York, where The Fix was masterminded.

Rather, the anomaly arose in Chicago, right in the shadow of Comiskey Park: at James O’Leary’s handbook in the Stockyards District on the South Side.

Celebrity Betting Practices

There is no doubt celebrity and quasi-professional bettors wagered on the 1919 World Series. Under the headline, “Celebrities Were There,” the Dayton Daily News identified a roster of celebrities present in the lobby of the Sinton Hotel in Cincinnati, including members of the National Commission, theater magnate George M. Cohan, former boxer Abe Attell, and a host of major-league ballplayers, including Chicago Cubs shortstop Joe Tinker, who the newspaper caught “listening in while his friend tried to place a bet on the later battered Hose team.”39

There is no doubt celebrity and quasi-professional bettors wagered on the 1919 World Series. Under the headline, “Celebrities Were There,” the Dayton Daily News identified a roster of celebrities present in the lobby of the Sinton Hotel in Cincinnati, including members of the National Commission, theater magnate George M. Cohan, former boxer Abe Attell, and a host of major-league ballplayers, including Chicago Cubs shortstop Joe Tinker, who the newspaper caught “listening in while his friend tried to place a bet on the later battered Hose team.”39

But the Dayton Daily News did not mention the most famous gambler in Cincinnati for Game One of the Word Series: Nick “The Greek” Dandolos. By the time Game One arrived, Nick the Greek already was a gambling legend in Chicago and beyond. In 1919, in addition to wagering on the World Series, he reportedly “broke one of the roulette banks in Monte Carlo.”40

According to the Chicago Tribune, on the morning of Game One, Nick the Greek “wagered $6,500 [$98,970.59] on the Sox against $5,000 [-130, 56.52%].”41 The report does not identify who booked Nick the Greek’s bet, but the bet is strong evidence that the White Sox remained the favorite the morning of Game One and that Nick the Greek did not have any knowledge of The Fix that morning.

Broadway actor and writer George M. Cohan also was a hard-core baseball fan and a respected sports bettor in 1919. On the morning of Game One, Cohan was in the lobby “all foxed up and ready to applaud any good playing, although a supporter of the Reds.”42 The Cincinnati Enquirer probably believed Cohan was backing Cincinnati before Game One because Cohan had been in Cincinnati on September 27 on theater business, attended one of the Reds’ last regular season games, and “announced after the game that he would back the Reds in the coming world series if he received the proper odds.”43

On the other hand, on October 2, the Akron Beacon Journal reported Cohan “came here as a White Sox supporter, and brought something like $25,000 to place on the Gibsonites.”44

In Eight Men Out, Eliot Asinof claimed Cohan did not bet his bankroll ($30,000) in Cincinnati on the White Sox because fixer Abe Attell tipped Cohan off that “The Fix was in” and Cohan switched his backing to the Reds via a phone call to direct his partner, Sam Harris, to bet Cincinnati in New York.45

No evidence of Cohan giving such direction has been found. Also, the need for Attell’s tip is contradicted by Cohan’s own September 27 statements to the Cincinnati Enquirer that he was strongly considering backing Cincinnati to win the World Series days before Asinof claims he ran into Attell.46

There is still more evidence that contradicts Asinof’s theory. On October 2, after the White Sox lost Game One, the Pittsburgh Daily Post reported that “George Cohan [still] wanted to bet $25,000 on the Sox before the second game.”47 Likewise, the St. Louis Star and Times reported “George Cohan is carrying a roll of $25,000 and he is still anxious to wager that the Chicago White Sox will win the series. At game time today Mr. Cohan had placed little of his money.”48

On October 4, the Star-Gazette in Elmira, New York reported “George Cohan was around the Blackstone lobby yesterday [before Game Three in Chicago] toting a bank roll that was big enough to choke a hippo. The Yankee Doodle Boy wanted to bet on the Sox despite anything and everything.”49 On October 6, with the Reds dominating the Series 4 games to 1, the Boston Globe reported, “Even the World’s Series fails to cheer George M. Cohan. He has been backing the Sox.”50

The only first-hand 1919 reports of Abe Attell’s betting that could be located were from James C. O’Leary of the Boston Globe (presumably no relation to the eponymous Chicago bookmaker.)

On October 2, O’Leary reported from Cincinnati that “Abe Attell won about $2500 [$38,065 in today’s dollars] on yesterday’s game and is playing the Moranites to win again today.”51 The next day, O’Leary reported:

Abe Attell, who cleaned up about $2500 yesterday, repeated today, and altogether has cleaned up about $10,000 [$145,148.46 in today’s dollars] on the two business days. It has been said that Abe is betting George Cohan’s money.52

O’Leary’s reports corroborate that Abe Attell was in Cincinnati, betting, doing very well, and possibly assisting George Cohan. But O’Leary’s account of Attell’s behavior is still more muted and mundane than the legend created by James Crusinberry’s 1956 account in Sports Illustrated.

Crusinberry claimed he saw Attell in the Sinton Hotel lobby the morning of Game One “standing on a chair — his hands filled with paper money — calling for wagers on the ball games. … He was waiving big money. There were $1,000 bills between his fingers of both hands and he was yelling in a loud voice that he would cover any amount of Chicago money.”53

There are numerous reasons to doubt Crusinberry’s claim. First, the media recognized Attell as a “celebrity” as evidenced by the Dayton Daily News including him on its “World Series Celebrity A-List.” But there are no 1919 reports of Attell standing on a chair, booking bets, and making it rain $1,000 bills. If such a scene occurred, it seems likely the media would have reported it.

Most conspicuously, reports from Crusinberry’s own paper, the Chicago Tribune, do not report anything at all about Attell. Rather, the paper reported the most attention-grabbing activity occurring in the Sinton Hotel lobby the morning of Game One was White Sox first baseman Chick Gandil mending fences over breakfast with Cleveland outfielder Tris Speaker following their fistfight at Comiskey Park earlier in the season.54

The story Crusinberry filed for the Tribune gave no indication that he believed gambling was influencing play on the diamond, but rather Chicago merely had been overconfident of its superiority. Crusinberry wrote:

When an 8 to 5 favorite in a world’s series is beaten by a score of 9 to 1 in the first game, it looks as if all the dope has been upset and all the wise experts are cuckoos. Before the Sox began the combat today, the betting was 8 to 5 in their favor, but the Reds beat them just the same. Something was wrong, and it looks as if it was nothing else but overconfidence on the part of Chicago’s team.

If that was the main cause of defeat, the severe beating was better than if the Sox had hooked up in a close contest and lost. There will be no overconfidence tomorrow when they meet the Reds in the second battle. The confidence may be on the other side. The best thing that could have happened to the Sox in their present mental condition was the crushing defeat today. From now on they will fight.55

Second, reports of conspicuous, big betting in Cincinnati did emerge, but not until after the World Series started and the betting did not involve Attell and it was not at the Sinton Hotel. Westbrook Pegler reported “a party of wild Western oil men” bet thousands of dollars on both the White Sox and the Reds from their seats behind home plate before Game Two.56 The New York Times reported after Cincinnati won Game One: “Betting appeared more active in the Hotel Havlin than in any of the other hotels, with the Reds as favorites.”57

Third, by 1919, boxers in general and Attell in particular were already perceived by the media and public as sketchy figures. In 1912, accusations were so strong that Attell had attempted to fix his fight with “Harlem Tommy” Murphy that Attell threatened to sue for libel.58

The media’s low expectations for boxers like Attell is perhaps best illustrated by a 1906 report in The Daily Times of Davenport, Iowa, which opined with respect to another fighter, “[he] is about 32 years of age and has been fighting for more than 12 years. … While he may have participated in one or two fakes, he has not done so often enough to be classed a ‘crooked boxer.’”59

Finally, perhaps most importantly, unlike Chicago, Cincinnati was definitely not a “wide open” gambling town when the 1919 World Series arrived. After Henry T. Hunt claimed the mayor’s office, Cincinnati law enforcement created a “gambling squad” that by the end of 1916 shut down all sports betting handbooks in the city and drove gambling across the Ohio River to Newport, Kentucky.60

Cincinnati law enforcement’s gambling squad appears to have been on high alert when the Latonia race track — now known as Turfway Park, located just 10 miles from downtown Cincinnati across the Ohio River in Northern Kentucky — held a meet.61

In 1914, Ohio native Hugh Fullerton documented Cincinnati City Hall’s “crusade” against sports betting handbooks as part of a three-party series he wrote for The American Magazine. In that series, Fullerton wrote, “Cincinnati affords a unique case proving that gambling can be suppressed if the authorities really desire it.”62 In Eight Men Out, Asinof claimed it was Fullerton who saw Attell making a scene in the Sinton Hotel.63 But no evidence that Fullerton ever made this particular claim has been located.

Further, no evidence was found to support Asinof’s claim that Fullerton wired a pre-Game One warning to the newspapers that published his syndicated column and advised them to print “ADVISE ALL NOT TO BET ON THIS SERIES. UGLY RUMORS AFLOAT.” It is clear Fullerton did not mention that he had issued such a warning in his post-World Series reports that were published on October 10 and December 15 of 1919 or in his reports in the immediate aftermath of the White Sox player confessions to the grand jury on October 3 and October 20, 1920.64

Rather, Fullerton did not make any claim until 1935 to have seen The Fix coming and to have tried to warn the public not to bet when he made the claim in a column for The Sporting News.65

Fullerton’s pre-Game One confidence in the White Sox appears to have evolved in the weeks leading up to the meeting in Cincinnati. On September 18, 1919, Fullerton wrote, “The world’s series of 1919 presents one of the toughest doping problems ever offered.” He added the Chicago vs. Cincinnati matchup “is unlike any ever played in modern baseball with the exception of the battle royal between Detroit and Pittsburgh [in 1909].”66

On September 30, after putting the matchup through his system,67 Fullerton concluded “Chicago’s White Sox dope to win the world’s series in five out of eight games. The extension of the series to nine games gives the Reds three victories and prolongs the struggle which in a four out of seven series the White Sox probably would have won in four out of five — on the dope.”68

It appears that it was not until October 6, after the Reds had taken an insurmountable 4-1 lead, that Fullerton first publicly articulated concern about the integrity of the World Series. On that day, under the sub-headline, “More Ugly Talk Heard,” newspapers in San Francisco and Muncie published Fullerton’s report which raised the issue that gamblers might be trying to fix the World Series. However, Fullerton concluded his report by saying that fixing the Series would be impossible:

There is more ugly talk and more suspicion among the fans and among others in this series than there ever has been in any word’s series. The rumors of crookedness, of fixed games and plots are thick. It is not necessary to dignify them by telling what they are, but the sad part is that such suspicion of baseball is so widespread.

There are three different lies making the rounds — all equally ridiculous. The only answer to such stories is that if anyone can evolve a way of making baseball crooked without being discovered in his second crooked move he probably could peddle his secret to some owners for a million. It cannot be done.69

Why would Fullerton have felt the need to warn the public before Game One against betting on the World Series if he still believed after the White Sox had fallen behind 4-1 that The Fix could actually be executed was “ridiculous?” To believe Fullerton voluntarily assumed a duty to warn anyone before Game One is to believe he acted to warn against an idea he (publicly) said was absurd. This would have risked jeopardizing his long-standing relationships in baseball — particularly with Chicago owner Charles Comiskey — with little or no expectation of positive compensation in return.

Based on the information available that reflects Fullerton’s measured and rational appetite for risk and his studious acquisition of knowledge of odds and gambling, it seems incredible that Fullerton would have been willing to stake his reputation on such a crazy bet by giving a pre-Game One warning based on an event he believed could not actually could occur.

This is not to say Fullerton and/or Crusinberry were negligent in the fall of 1919 or that they were deceitful or deceptive decades later when they recalled the events that swirled around the World Series. Rather, it is more likely that with the passage of time, memory failure, memory distortion, and personal biases led them to consolidate events into a single time and/or to lose a firm grasp of the subtler details.70

There is no doubt both Fullerton and Crusinberry chased the story of The Fix in the immediate aftermath of the 1919 World Series. But it is also likely that the more dramatic elements they did not mention until long after their post-Series investigations had ended were embellishments characteristic of how the news business operated in the early 20th century. These have grown into urban legends despite the absence of a strong evidentiary foundation in reality.

To believe otherwise is to believe a boxer and accused fixer (Abe Attell) stood on a chair in a media maelstrom in the Sinton Hotel in front of baseball’s National Commission in a town that was completing a “crusade” to eradicate sports betting handbooks and relentlessly booked bets — except for $25,000 that was available from the Chicago Board of Trade — until he had $1,000 bills raining from the rafters.

It seems unlikely that even a punch-drunk, ex-fighter like Abe Attell would be that reckless in public.71 And if Attell was that stupid, you would think the media would have paid more attention at the time.

Expert Odds-Making

As a micro-examination of the betting of celebrity/quasi-professional bettors on the 1919 World Series yields valuable insight into how the betting markets were behaving before and during the Series, an examination of high profile odds-makers Jack Doyle and James O’Leary yields valuable insight.

As a micro-examination of the betting of celebrity/quasi-professional bettors on the 1919 World Series yields valuable insight into how the betting markets were behaving before and during the Series, an examination of high profile odds-makers Jack Doyle and James O’Leary yields valuable insight.

In Eight Men Out, Eliot Asinof wrote, “In New York, Jack Doyle’s betting establishment had witnessed a sudden sweep of Cincinnati money that had jolted the odds from 7-10 to 5-6” and implied this movement in the odds demonstrated “that the word [that The Fix was in] was spreading.”72 Asinof’s conclusion lacks any context and when this movement in the odds is put into proper context, it is clear that Asinof’s conclusion is dubious at best.

At the time of the 1919 World Series, Jack Doyle probably was the most respected odds-maker in the United States. Asinof’s own source noted that Doyle “manages to keep his finger on the public pulse with a pretty certain degree of accuracy.”73 In its obituary of Doyle, the New York Daily News observed:

He quoted odds on all presidential elections and other political fights; set the “line” on the big league pennant races; made the Winter book prices on the Kentucky Derby; and gave betting figures in all important racing stakes, football games, fights and other sports events.

His word was gospel in the gambling world. The newspapers accepted his quotations without question and pinned the honorary title of “Betting Commissioner” on him.74

Further, no odds-maker was more plugged into baseball than Doyle. His partner when he opened his first pool hall in New York was none other than New York Giants manager John McGraw, who remained a life-long friend.75 He held pool tournaments for newspapermen in New York, including Grantland Rice.76 Finally, most importantly, he had a long relationship with Giants first baseman Hal Chase, a pool hustler who played in Doyle’s establishment, sometimes worked for Doyle as a cashier,77 and indisputably had prior knowledge of The Fix.78 If any person in the business of betting outside the fixers was likely to know about The Fix, it was Doyle.

But there is no evidence that Doyle knew about The Fix before Game One. If he did, he might not have taken bets on the World Series or, at least, not taken bets on the Reds. However, even if he knew, he still could have taken the bet on Cincinnati.

Given Doyle’s position in the business of betting in New York and his access to information, the fact Doyle covered a significant bet on the Reds indicates only that Doyle had plenty of White Sox money to off-set the bet,79 not that the bettor who backed the Cincinnati knew that “The Fix was in.” There is no evidence in the historical record that odds-making, bookmaking, and betting at Jack Doyle’s reflected anything other than “business as usual” during the 1919 World Series.

The same cannot be said for the odds-making, bookmaking, and betting at James O’Leary’s handbook in the Stockyards District of the South Side of Chicago. It is at O’Leary’s — and only at O’Leary’s — where the betting market on the 1919 World Series looks peculiar.

The same cannot be said for the odds-making, bookmaking, and betting at James O’Leary’s handbook in the Stockyards District of the South Side of Chicago. It is at O’Leary’s — and only at O’Leary’s — where the betting market on the 1919 World Series looks peculiar.

Pursuant to Professor Strumpf’s findings that bookmakers possess market power to charge backers of hometown sentimental favorite teams more in the form of stronger-than-market odds, the odds on the White Sox in O’Leary’s handbook should have been stronger than anywhere else in the country given its location in the shadow of Comiskey Park.

Interest in Chicago in the World Series was massive: the franchise was flooded with 100,000 ticket applications for 18,000 seats at Comiskey Park and the Internal Revenue Service announced it would send 40 agents to Chicago to chase a 50 percent tax applicable to scalped tickets.80 O’Leary should have been awash in White Sox money, much like Rhode Island sports books were awash in New England Patriots money in 2019 when the Patriots defeated the Los Angeles Rams in Super Bowl LIII.81

But that does not appear to have been the case. On October 1, 1919, under the headline “Red Money Appears,” the Chicago Tribune reported:

At the establishment of Jim O’Leary, near the stockyards, the best known clearinghouse for wagers in this city, Cincinnati money was more in evidence than White Sox coin yesterday. As a result the odds which had been current around the city, were changed, bringing the Reds nearer to an even money proposition.

O’Leary last night [September 30] quoted the odds at this place as 5 to 4 on the Sox [+125, 44.44%] to win the Series and 5 to 6 on Cincinnati [-120, 54.55%]. He did not handle bets on the first game. Much of the money which arrived to depress the odds given the Reds was from out of town. There was considerable wagering.82

Such strong backing of Cincinnati at O’Leary’s handbook must have come as a shock. After all, the Chicago Board of Trade and the Woodland Bards reportedly took a combined $58,000 [$883,123.06 in today’s dollars] to Cincinnati before Game One because they expected to find weaker odds on the White Sox in Cincinnati than were available when they left Chicago [13-20, -153.85, 60.61%].83

The change in the odds in Chicago after the city’s big bettors left for Cincinnati seems to have surprised those who remained in Chicago. On October 3, the New York Times reported:

White Sox fans who are here for the series reported that telegrams from their home city indicated that plenty of Cincinnati money had appeared upon Lake Michigan’s border, and that it was aggressive money — so aggressive in fact that White Sox supporters could get even better terms for their wagers in Chicago than in Cincinnati.84

Confronted with the wave of Reds money, it appears that O’Leary plunged deeply on the White Sox by opening his handbook to action on Cincinnati on the morning of Game One. In a special dispatch from Chicago on October 2, Walter Eckersall of the Cincinnati Enquirer reported:

In the Stock Yards district a lot of money was won on the Reds. According to a well-known gambler the tip went out through the yards that Cicotte was not in his best form, and as soon as it was known he was Manager Gleason’s selection there was enough Cincinnati money to cover all Sox offerings.85

That a bookmaker like O’Leary would form and back an opinion and plunge on the White Sox is not suspicious. After all, Professor Strumpf found that bookmakers are not risk averse, but rather gamble and take positions on games. Clearly, the evidence that O’Leary refused action on Game One until after the big Chicago bettors left for Cincinnati and then plunged deeply on the hometown White Sox shows that he believed strongly in the Sox and wanted to back his opinion that Chicago would prevail in both Game One and also the entire Series.86

It also seems clear O’Leary had no knowledge of The Fix, given that he was one of the biggest bookmakers in Chicago and doing business in the same neighborhood where the White Sox played their home games. The Fix was a well-kept secret prior to Game One and few saw the Black Sox Scandal coming.

While O’Leary’s odds-making and bookmaking behavior is understandable, questions abound regarding the “aggressive out-of-town money” that flooded his handbook with action on the Reds. Who aggressively bet all that money on Cincinnati? Why did the bettors wager at stronger odds on the Reds with O’Leary when it appears they could have gotten weaker odds on the Reds in either New York or Cincinnati?

As Professor Strumpf found, gamblers are economically self-interested so it is puzzling why these Cincinnati backers appear to have chosen to pay a higher price to bet on the Reds and cost themselves marginal profits by hammering O’Leary.

These questions are intriguing and may never be definitively answered.

KEVIN P. BRAIG is a partner with the law firm of Shumaker, Loop & Kendrick, LLP and a member of the International Masters of Gaming Law.

Notes

1 Hugh Fullerton, “Hugh S. Fullerton Vividly Describes the Full Details Of Great Baseball Scandal,” Atlanta Constitution, October 3, 1919.

2 Koleman Strumpf, Illegal Sports Bookmakers (Chicago: University of Chicago, George J. Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State, 2003).

3 Fullerton, op. cit.

4 Ibid. Fullerton’s reference to his “one exception” is likely to the 1914 “Miracle” Boston Braves, who upset the Philadelphia A’s in a four-game sweep.

5 “Bookies Favor Sox,” Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1919. In 1919, odds on the World Series and other more exotic propositions — known in 1919 as “freak bets” — were expressed exclusively as “fractional odds,” e.g., “4 to 5.” For the purposes of this paper, odds also will expressed in brackets as “American odds” and “implied probability” that the outcome will actually occur, e.g. “[-125, 55.56%].”

6 Harvey T. Woodruff, “If Your Money Goes on Sox The Odds Are 13-20,” Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1919. Woodruff, the Tribune’s sports editor, also noted in this report, “One $10,000 pool from Cincinnati was placed at evens more than a week ago.” That is, after the Reds clinched the National League pennant on September 16, but before Chicago clinched the American League pennant on September 24.

7 Ibid. This shift in the odds in the direction of the White Sox despite a large bet on Cincinnati ($121,809 in today’s dollars) is evidence Chicago’s status as the favorite was strengthening at this time and place.

8 Rumors of 2 to 1 odds [-200, 66.67%] in Boston were reported in Cincinnati, but no local Boston newspaper reporting such odds could be located. See Jack Ryder, “Sallee and Cicotte May Open World Series in Cincinnati,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 30, 1919.

9 Bozeman Bulger, “Within Hour After Brooklyn Had Clinched the National League Pennant $3,500 Was Deposited at Doyle’s to Be Wagered Against $2,500 That Boston Wins Championship,” The (New York) Evening World, October 4, 1916.

10 Sports Odds History, https://www.sportsoddshistory.com/mlb-odds . The strongest favorite to win the World Series since 1985 was the 1990 Oakland A’s, who were 1 to 3 favorites [-300, 75.00%] to beat Cincinnati. However, as in 1919, the Reds confounded the “dope” and swept the A’s, a result that truly can be classified as shocking!

11 Eliot Asinof, Eight Men Out: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series, (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1963), 42-43.

12 “Gothamites Dig Up Some Bets on Reds,” New York Times, October 1, 1919. Some observers began questioning Cicotte’s fitness as early as September 5, when he walked a season-high six batters in a win over Cleveland. See I.E. Sanborn, “Cicotte Puts Sox Within One Game of Clinching the Flag,” Chicago Tribune, September 20, 1919.

13 Christy Mathewson, “Matty Says Reds May Fool Experts,” New York Times, September 28, 1919.

14 In his last two 1919 regular-season appearances, Cicotte pitched 9 innings and posted a 6.00 ERA and 1.67 WHIP. It is generally accepted that sports betting is an environment where many inhabitants are prone to “recency bias,” where a person remembers or overvalues events that happened most recently at the expense of in disproportionate value to events that occurred at a point more remote in time.

15 Frederick J. Lieb, “Broken Finger Kept Groh On The Sidelines,” New York Herald, September 30, 1919.

16 “Cicotte vs. Ruther, Say Rival Managers,” Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1919.

17 W.O. McGeehan, “Heinie Groh’s Sore Finger, Which Was the Cause of Some Worriment, Reported To Be Better and He Will Be in Trim for Battle in Big Series,” New York Tribune, September 30, 1919.

18 Ryder, op. cit.

19 Ibid. See also Dan Daniel, “High Lights And Shadows In All Spheres Of Sport,” New York Tribune, September 29, 1919; James O’Leary, “New England Fans Head For Redland,” Boston Globe, September 29, 1919; Dan Daniel, “Cincinnati Fans Unwilling to Back Talk With Wagers,” New York Herald, September 30, 1919; James O’Leary, “Reds Confident, White Sox Also — Odds 6 to 5 on Latter,” Boston Globe, September 30, 1919.

20 Woodruff, op. cit.

21 “Sox Rule 7 to 5 Choice In Cincy,” Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1919.

22 Cincinnati Enquirer, October 1, 1919.

23 “Nick the Greek’s $6,500 Goes on Sox to Cop Series,” Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1919.

24 “Reds Fans Refuse To Give Big Odds,” New York Times, October 2, 1919; “Offer 9 to 5 on Reds,” New York Times, October 3, 1919.

25 “Scores Posted In Cincinnati Schools,” New York Times, October 3, 1919. The Woodland Bards was an informal gentlemen’s club organized by White Sox team owner Charles Comiskey in the early 1900s whose membership included most of Chicago’s political power brokers, top businessmen, sportswriters, and celebrities, as well as prominent ballplayers.

26 “Betting Now Favors Reds,” Boston Globe, October 3, 1919.

27 “New York Betting Favors Reds to Win by 7 to 10,” Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1919.

28 “Betting Now Favors Reds,” Boston Globe, October 3, 1919.

29 “Nick the Greek’s $6,500 Goes on Sox to Cop Series,” op. cit.

30 Even with a 2-0 lead in the World Series, it appears a few unreasonably stubborn Cincinnati backers were demanding even money odds before Game Three. Jack Casey, a writer with the Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph, said, “‘The series so far has had more surprises in it than a Kentuckian has liquor. Cincinnati is the birthplace of the hard-boiled egg. Think of a gang of fans wanting even money on a team that has won two games. They were yelling at first that they wanted odds of eight to five before the series started, and now when the Reds have the jump they demand even money.’” See “American League Scribes Waver in Hopes For White Sox,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 3, 1919.

31 Walter Eckersall, “Sharps Are Laying 5 To 3 That Cincinnati Will Be Champions of World; Betters Find Plenty of Queen City Cash,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 3, 1919.

32 Cincinnati Enquirer, October 4, 1919.

33 “Chicago Fans Not Betting; New York Supporters of White Sox Refuse 4 ½ to 1 Odds,” New York Times, October 3, 1919.

34 Bozeman Bulger, “Backers of the White Sox Refused to Hedge Bets Even With Reds in Front,” The (New York) Evening World, October 4, 1919. Like those 1919 betting commissioners, the author is confused as to whom Bulger was identifying as the favorite. Given the context of the paragraph in which the odds appear, it appears Chicago again had become the favorite. But it would also be reasonable to interpret that Cincinnati remained the favorite, albeit a weaker one. For purposes of this analysis, it is of little matter which team actually was the favorite after Game Three. The odds and narrative reporting clearly demonstrate that the bettors again considered the matchup as still “up for grabs.”

35 “Local Odds Are 6 To 1,” New York Times, October 5, 1919.

36 “Reds Favored At 7 To 2; Chicago Fans Complain Odds Are Too Short and Refuse to Bet,” New York Times, October 5, 1919.

37 “Moran Beams with Joy,” New York Times, October 6, 1919.

38 “Series Betting Ends,” New York Times, October 6, 1919; “No Sox Rooters Left In Gotham,” Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1919.

39 “Celebrities Were There,” Dayton Daily News, October 2, 1919.

40 Paul O’Neil, “Nick The Greek’s Last Role,” Life Magazine, January 6, 1967.

41 “Nick the Greek’s $6,500 Goes on Sox to Cop Series,” Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1919.

42 “Celebrities Were There,” op. cit.

43 “Stage Received Setback When Actors Went on Strike, George M. Cohan Declares,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 27, 1919.

44 Jack Veiock, “Moran Will Again Send Left Hander Against White Sox,” Akron Beacon Journal, October 2, 1919.

45 Asinof, 42.

46 Cincinnati Enquirer, September 27, 1919.

47 Pittsburgh Daily Post, October 2, 1919.

48 James M. Gould, “Cincinnati Fans Wild to See Ruether Again,” St. Louis Star and Times, October 2, 1919.

49 “That Reminds Me,” The (Elmira, New York) Star-Gazette, October 4, 1919.

50 “George Cohan To Try Out his Daughter As An Actress,” Boston Globe, October 6, 1919.

51 James C. O’Leary, “Reds Now Favorites in Betting on Account of Win Yesterday,” Boston Globe, October 2, 1919.

52 James C. O’Leary, “Reds Capture Second Game,” Boston Globe, October 3, 1919.

53 James Crusinberry, “A Newsman’s Biggest Story,” Sports Illustrated, September 17, 1956. Accessed online at https://www.si.com/vault/issue/42194/72 on June 2, 2019.

54 “Speaker, Gandil Pals Once More,” Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1919.

55 James Crusinberry, “Defeat To Spur Gleason’s Team To Real Fighting,” Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1919.

56 J.W. Pegler, “Cincinnati Taken By ‘Coal-Oil Kids;’ Wahoo! Coin Flies,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, October 3, 1919.

57 “Offer 9 to 5 on Reds,” New York Times, October 3, 1919. Heavier betting at the Havlin Hotel than at the Sinton Hotel makes better historical sense. First, the members of the National Commission, including American League President Ban Johnson — who had been making anti-gambling noises for years — were staying at the Sinton Hotel, so open and notorious betting would have been right under the Commission’s turned-up noses. Second, the Woodland Bards — the heavy-betting White Sox backers — rented an entire floor at the Havlin Hotel. See “Rooters Recall Days of Yore in Cincinnati, To Old-Timers,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 1, 1919. Third, perhaps the last well-known, open, and notorious illegal bookmaker to operate in downtown Cincinnati was a horsemen and cigar dealer named Sam Hirsch, who reportedly did business in the Havlin Hotel. See “‘Desist!’ Cries Attorney Mueller; And Sleuths Stop Cracking Safe To Hold Palavar; Melodramatic Raid Made on Offices of Sam Hirsch; Alleged Bet Notations and Codes Are Found – Telephone Nestles Within a Vault,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 14, 1916.

58 “Abe Attell to Sue Buckley for $20,000 for Charging He Tried to Fake,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 12, 1912; “Did Buckley Tell All He Knew of Puzzling Attell-Murphy Match?” San Francisco Examiner, March 13, 1912.

59 “Greatest Battle in Past Decade,” The (Davenport, Iowa) Daily Times, September 3, 1906.

60 “New Gambling War Planned,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 26, 1916; “Sam Hirsch Punished,” The Labor Advocate, November 18, 1916; “Burden Placed Upon Officials; Former Mayor Hunt Tells Newport Audience ‘Tis Possible to Suppress Professional Gambling,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 20, 1916.

61 “Chair Hurled By Raider,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 11, 1919.

62 Hugh Fullerton, “American Gambling and Gamblers: Preying Upon Wager Earners,” The American Magazine, February 1914.

63 Asinof, 47.

64 See Hugh Fullerton, “Team Which Stuck Together Won Title, Declares Fullerton,” San Francisco Examiner, October 10, 1919; “Is Big League Baseball Being Run For Gamblers, With Players In The Deal?” The (New York) Evening World, December 15, 1919; “Hugh S. Fullerton Vividly Describes the Full Details Of Great Baseball Scandal,” Atlanta Constitution, October 3, 1920; and “Baseball On Trial,” New Republic, October 20, 1920.

65 Hugh Fullerton, “I Recall,” The Sporting News, October 17, 1935.

66 Hugh Fullerton, “1919 World’s Series Difficult to Figure Declares Fullerton,” San Francisco Examiner, September 18, 1919.

67 Ibid. Fullerton described his “system” as follows: “The full strength of a team is 100 percent. If the defensive value of all teams exactly equaled the attacking value no team ever would score a run. By taking figures for a dozen years, I discovered that the attacking strength of any team is 64 percent and the defensive strength is 36 percent. Those figures may not be exactly right, but they are approximately correct. I reached the figure by taking the number of bases advanced in comparison with outs and the proportion holds good year after year. That means that batting, base running, etc. all the elements of attack, are more valuable than the elements of defense.” An analysis of Fullerton’s system is beyond the scope of this paper.

68 Hugh Fullerton, “Dope On The World’s Series,” Wichita Daily Eagle, September 30, 1919.

69 Hugh Fullerton, “White Sox Roiled, No Doubt About It; But Fullerton Dopes A Victory For Them if It’s Williams vs. Ruether; Ugly Talk and Suspicion,” The (Muncie, Indiana) Star Press, October 6, 1919; Hugh Fullerton, “Chisox Should Beat Ruether Next Time Out, Says Fullerton,” San Francisco Examiner, October 6, 1919.

70 See, e.g. Lumen Learning, Memory Distortions , accessed online on June 2, 2019.

71 It also seems incredible that Sleepy Bill Burns told Fullerton to “get wise and get yourself some money” the day before Game One. Again, Fullerton never made this claim in 1919 or 1920, but first made this claim as a witness in Shoeless Joe Jackson’s 1924 trial for back pay. It would have been reckless indeed for Burns to even hint of The Fix to Fullerton before Game One. By 1919, Fullerton had thoroughly published his distaste for gambling on baseball. Some writers, like Grantland Rice, who reportedly participated in a media pool tournament at Jack Doyle’s pool room in Times Square and golfed regularly with Babe Ruth, appear to have been comfortable with gambling on baseball. But Fullerton’s position on gambling was more nuanced. Fullerton distinguished between “gambling” and “sure thing play” and he considered New York gamblers to engage in only the latter. See Hugh Fullerton, “American Gambling and Gamblers: Preying Upon the Wage Earners,” The American Magazine, February 1914. Given Fullerton’s bias against New York gamblers and his enthusiasm for revealing objective truth, it does not seem possible that Fullerton could have cultivated a relationship with a person like Burns that would have put Burns at ease to tell him “get wise and get yourself some money.” If Burns in fact told Fullerton as much, then Burns was as reckless and stupid as Attell.

72 Asinof, 42. According to the New York Times, the bet Doyle covered was “$5,000 to $7,000 on the Reds.” In other words, the bettor appears to have risked $5,000 to win $7,000, which is equivalent to odds of 7 to 5 [+140, 41.67%]. This would have been approximately consistent with the odds reported in Chicago the day before (September 29) on the White Sox [13 to 20, -153.85, 60.61%] and exactly the odds that Harvey T. Woodruff of the Chicago Tribune opined the odds should be.

73 “Gothamites Dig Up Some Bets On Reds,” op. cit.

74 “Doyle, Betting Chief, Dies,” New York Daily News, December 10, 1942.

75 Jimmy Powers, “The Powerhouose,” New York Daily News, December 7, 1937.

76 “Oyez! Pool Sharks! Jack Doyle Calls; Tourney for Newspaper Men Will Open on Monday,” New York Tribune, November 25, 1915.

77 Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 56.

78 “Hal Chase Dies In California,” Tucson Daily Citizen, May 19, 1947: “’Sure, I knew about [The Fix],’ Chase said not long ago, ‘But I was no squealer.’”

79 “Gothamites Dig Up Some Bets On Reds,” op. cit.; “Times Sq. Crowd Grows; More Thousands of ‘Standees’ See Second Scoreboard Game,” New York Times, October 3, 1919.

80 Harvey T. Woodruff, “Lucky Fans To Get Tickets Tomorrow; Many To Shed Tears,” Chicago Tribune, September 28, 1919; “Forty Federal Sleuths After Ticket Scalpers; Collect 50 Per Cent Tax from Speculators, Who Hold Few Ducats,” Chicago Tribune, September 30, 1919.

81 Associated Press, “Rhode Island sportsbooks took massive hit when the Patriots won the Super Bowl,” Boston Globe, April 2, 2019.

82 “Red Money Appears,” Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1919. Only this single report on O’Leary’s operations provides any evidence of how bookmakers in 1919 set “margins.” Because O’Leary’s odds on the White Sox and the Reds sum to 99.99%, he was creating a market with zero margin. The existence of zero-margin odds at O’Leary’s suggests he was behaving like “just another gambler” rather than a bookmaker. Margins in baseball tend to be quite low, sometimes as low as 1.5%, and typically not greater than 5%. But it is very, very rare to offer zero-margin bets on baseball; doing so is essentially forfeiting the inherent edge of being the bookmaker — which is establishing odds that favor the bookmaker. For an explanation on how bookmakers calculate betting margins to both attract business and profit, see “How to calculate betting margins,” Pinnacle.com, August 15, 2016, accessed online on June 2, 2019.

83 Woodruff, “If Your Money Goes on Sox The Odds Are 13-20.”

84 “Offer 9 to 5 On Reds,” New York Times, October 3, 1919.

85 Walter Eckersall, “Plenty of Queen City Money Shows Up,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 2, 1919.

86 Perhaps the most delicious fact about the 1919 World Series for Cincinnati Reds fans (like the author) is that so many purportedly “square” Reds’ backers bet like “sharps” and the so-called “sharp” White Sox backer, James O’Leary, bet like a “square.” After Cincinnati grabbed the early 2-0 lead in the World Series, the New York Times observed “Apparently, the majority of Cincinnati fans of the cooler type, men who never allow partisanship or prejudice to sway reason in matters where money is concerned, are not really eager to lay two to one that the Reds will prove masters of the situation.” See “Offer 9 To 5 On Reds,” New York Times, October 3, 1919. Alas, not all Cincinnati backers were of the “cooler type” who made a killing. For example, an October 8, 1919 headline in the New York Times blared “Seven Redland Fans Lose $60,000 on Game” [$913,574.55 in today’s dollars], and the Times reported “[t]hey wagered $15,000 at odds on the first game. They doubled on the second and third game. Losing on the third game they dropped their betting to $15,000, won, and then bet $30,000 on the fifth game, which they also won. They then bet the $60,000 on the sixth game.”