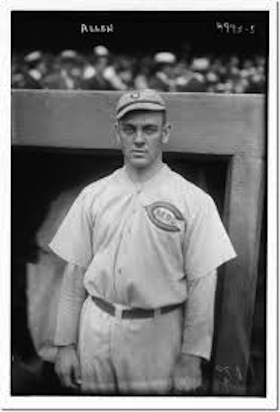

Hod Eller

There was no mention of the “shine ball” before 1917, but the pitch was the talk of the 1917 season. Eddie Cicotte and Dave Danforth of the Chicago White Sox were its foremost practitioners. Christy Mathewson explained how the new pitch differed from the “emery ball”:

There was no mention of the “shine ball” before 1917, but the pitch was the talk of the 1917 season. Eddie Cicotte and Dave Danforth of the Chicago White Sox were its foremost practitioners. Christy Mathewson explained how the new pitch differed from the “emery ball”:

“In throwing the ‘emery,’ a pitcher roughens a spot on the cover [of the ball]. The contact of the air against this roughened surface causes the ball to take peculiar breaks, and in the hands of a pitcher who can control it, it is almost unhittable. In pitching the ‘shine,’ the hurler smoothes a spot on the ball until it is so slick that the rest of the surface is so rough in comparison.”1

In 1917 Mathewson managed the Cincinnati Reds. He added this comment:

“Hod Eller, one of my young pitchers, is the only hurler in our league whom I knew to have used the ‘shine.’ Eller has been experimenting with it and standing the catchers on their heads.”2

Hod Eller mastered the shine ball, and from 1917 to 1919, he compiled a 45-26 record and a 2.37 earned-run average for the Reds. He was on top of the world in October 1919 after winning two games against the White Sox in the infamous 1919 World Series. Two years later, his major-league career was over. This is the story of the rise and fall of a shine-ball pitcher.

Horace Owen “Hod” Eller was born on July 5, 1894, in Muncie, Indiana, the oldest of five sons born to William and Ella Eller. The family moved to Danville, Illinois, about 1901.3 According to US Census records, William worked at a glass factory in 1900 and at a powerhouse in 1910. As a 15-year-old, Hod worked as a boilermaker at a railroad shop.

Hod pitched for the Champaign (Illinois) Velvets in 1913 and helped them win the pennant in the Class D Illinois-Missouri League. He moved up to the Class B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League in 1914, pitching for his hometown Danville Speakers. The struggling team relocated to Moline, Illinois, in late July. Eller pitched well for the last-place team with a 17-14 record in 268 innings.4 In 1915, he pitched for the pennant-winning Moline Plowboys5 and finished the season with a 19-15 record in 294 innings. The stocky right-hander was regarded as “the Walter Johnson of the circuit, having terrific speed as his biggest asset.”6 In the offseason Eller worked for the Danville fire department. He married Ruth Salmans in 1915, and their son, Harry, was born in 1916.

Eller went to spring training with the White Sox in 1916 but failed to make the team, so he returned to Moline for the 1916 season. After the Moline team suspended him in August over a contract dispute, he played on semipro teams for the rest of the season. In a game played in the rain on September 7 in Havana, Illinois, Eller pitched for the Henry (Illinois) Grays against the Cincinnati Reds. He gave up 11 hits in a 3-0 loss7 but impressed Mathewson and the Reds. They drafted him on September 15 and signed him to a contract in January 1917.

Eller pitched with a “side-arm motion” and with “very little windup.”8 After 16 relief appearances for the Reds, he was given his first start on June 11, 1917. The 22-year-old hurler allowed two runs on four hits in a complete-game victory over the Brooklyn Robins. Eight days later he started and completed both games of a doubleheader against the Chicago Cubs. Against the Boston Braves on July 9, Eller pitched his first major-league shutout.

Because Eller had interacted with Cicotte and Danforth at spring training in 1916, people assumed that he learned the shine ball from them, but Eller said he discovered the pitch on his own accidentally. He was brought in to pitch against the New York Giants on August 21, 1917. The ball was quite dirty, and “with no other thought than to be able to get a good grip of the ball,” he cleaned one side of the ball by rubbing it hard on his uniform.9 When Eller threw the ball to his catcher, Ivey Wingo, they noticed that the ball had made an unexpected break. Eller experimented further during the game, and in the ninth inning, he struck out three batters in a row on nine pitches, a rare feat. Intrigued by his discovery, he continued to experiment with it.

Eller finished the 1917 season with a 10-5 record and a 2.36 ERA. He won two more games in October as the Reds defeated the Cleveland Indians in a best-of-seven exhibition series dubbed the “Ohio Championship.” On the mound Eller frequently rubbed the ball on his uniform.10 Hal Chase, the Reds’ first baseman, bet $100 on the Reds to win Eller’s first game of the series, and then doubled down on the Reds to win Eller’s second game. “I believed Hod Eller could make monkeys of the Clevelands,” said Chase, who was surely aware of Eller’s new pitch.11 The Indians batted .169 against Eller in those two games.12

Shine-ball pitchers typically placed a spot of paraffin wax on their trousers and rubbed the ball on it to shine the ball. In 1917 American League managers Clark Griffith and Connie Mack lobbied AL President Ban Johnson to ban “paraffin pants”13 and other pitching “trickery.”14 White Sox owner Charles Comiskey defended his pitchers’ “artificial” deliveries. “Just as soon as a pitcher develops something good, they want to legislate it out of existence,” said Comiskey. “Cicotte is a smart pitcher and that’s why he wins.”15 In December 1917 the minor-league American Association took the unprecedented step of banning the spitball and “the entire freak delivery family.”16 A similar ban was under consideration in the major leagues.

Because Eller had dependents (a wife and son), he was exempt from the military draft during World War I. He went 16-12 with a 2.36 ERA for the Reds during the 1918 season. On July 25 he pitched all 13 innings, allowed only four hits, and struck out 11 batters in a 4-2 victory over the Braves. He won seven consecutive games in August. “Eller has done extremely good work for the Reds during the past two years, showing plenty of nerve and ambition,” wrote one reporter.17 Eller again worked for the Danville fire department in the offseason.18 His daughter, Mary Louise, was born in March 1919.

Pat Moran took over as Reds manager in 1919 and Eller was an integral member of his pitching staff. On May 11 Eller pitched a no-hitter against the St. Louis Cardinals. Jack Ryder of the Cincinnati Enquirer wrote, “Not a single hard ball was hit off him. … He worked rapidly, but not too hastily, and with a serene confidence.”19 Four days later, Eller threw a 13-inning shutout against Brooklyn. The “Danville Dandy” was on a roll, but his next start was a dud: six runs allowed to the Giants in 2⅓ innings.20

On June 24 Eller shut out the Cubs and recorded 10 strikeouts, but the Cubs got revenge a week later when they beat him 3-2 in 12 innings. The Cubs reported that Eller “carries in his hip pocket” a “mysterious substance” that makes the ball “take queer jumps.”21 Eller defeated the Braves in consecutive starts on July 8 and July 11, and he shut out Pittsburgh on July 25 and Brooklyn on August 7. The Cincinnati Enquirer crowed after the Brooklyn shutout (“his famous shine ball found its way to the mark with absolute precision”22) while the Brooklyn Daily Eagle fumed that Eller’s pitches were “tainted by the deadly paraffin.”23 His shine ball was “said to rival that of Eddie Cicotte, champion shiner of them all.”24

The shine ball requires contrasting smooth and rough surfaces and must be thrown with considerable speed. The “smooth spot was not worth anything unless there was a rough spot on the opposite side of the ball,” explained Eller.25 According to Reds outfielder Edd Roush, when a new ball was put in play, the Reds infielders would skip the ball on the dirt infield to roughen it up, and then Eller would apply paraffin to smooth a portion of the cover. “With that, he could break the pitch any way he wanted,” said Roush.26 If Eller released the ball with the smooth surface facing up, the pitch would break upward like a rising fastball. If he released the ball with the smooth surface facing down, the pitch would break downward.27

The Reds were in first place, 4½ games ahead of the second-place New York Giants, when the teams met on August 15, 1919, for a doubleheader. In the first game, Eller faced Giants ace Jesse Barnes. Eller’s record was 14-7; Barnes had a sterling 19-4 record and was on a 10-game winning streak. In the fourth inning Eller surprised everyone by clubbing a three-run homer into the left-field bleachers. It was his only major-league home run and was the difference in the Reds’ 4-3 victory. Eller allowed only six hits. The New York Times reported that “before he pitched the ball, he rubbed the cover against his uniform.”28 The Giants periodically asked home-plate umpire Bill Klem to inspect the ball.29

Outcry over Eller’s shine ball grew louder. Braves manager George Stallings and Cubs manager Fred Mitchell called for the pitch to be outlawed. Stallings said, “The way Hod Eller uses the shine ball is a crime. He puts enough paraffin on the ball to wax the top of an automobile. He has it in the seams and all over one side of the ball.”30

Eller ignored his critics and continued to shine. He defeated Brooklyn on August 19 by 6-1, and a week later, he fanned 10 Phillies en route to a 4-3 victory. He pitched two shutouts in September, against St. Louis and Brooklyn. In his final start of the season, Eller lost to Grover Cleveland Alexander and the Cubs, 2-0. Eller finished the 1919 season with a 19-9 record and a 2.39 ERA. He was second in the National League in strikeouts, and his seven shutouts were second in the league to Alexander’s nine.

The Reds won the NL pennant and were ready to take on Cicotte and the White Sox in the World Series. Brooklyn shortstop Ivy Olson said, “This Eller is a wonder, and when he is right I don’t see how the Sox can hit him. … He can make the ball do as many strange tricks as Cicotte.”31 NL batters “are convinced that Eller when primed is as nearly unhittable as any pitcher that ever lived,” wrote Thomas S. Rice in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.32 Would Eller “outshine” Cicotte in the Series? Mathewson predicted that Eller would “cut loose a shine ball far beyond anything Eddie Cicotte ever knew.”33 White Sox first baseman Chick Gandil scoffed and predicted that Eller would not last three innings against the White Sox.34

Cicotte lasted only 3⅔ innings against the Reds in Game One of the best-of-nine Series, and the Reds won easily, 9-1. Dutch Ruether pitched a gem for the Reds. In Game Two the Reds’ Slim Sallee outdueled Lefty Williams of the White Sox for the second Reds victory of the Series. Dickey Kerr of the White Sox hurled a three-hit shutout in Game Three to defeat Reds spitballer Ray Fisher. The Reds’ Jimmy Ring countered with his own three-hit shutout in Game Four opposite Cicotte.

After four games the Reds held a three-games-to-one lead over the White Sox and had twice defeated the great Cicotte. Reds fans wondered when Eller would pitch. Moran finally sent him to the mound to start Game Five against Williams. It was the first time that a team started five different pitchers in the first five games of a World Series. The Reds’ pitching depth was impressive.

Game Five was scheduled for October 5 at Comiskey Park in Chicago, but it was rained out and played the next day in front of 34,379 fans. Eller delivered a brilliant three-hit shutout in a 5-0 Reds victory. He threw 94 pitches,35 allowed one walk, and struck out nine batters, including a World Series record six consecutive strikeouts. His six victims were Gandil, Swede Risberg, and Ray Schalk in the second inning, followed by Williams, Nemo Leibold, and Eddie Collins in the third inning. Eller “received a tremendous ovation for his remarkable piece of pitching.”36 The Washington Herald said his pitches “twisted and turned and dipped and dropped in uncanny fashion.”37

Eller also delivered a big hit. In the sixth inning, he drove a pitch to the fence in left-center field for a double and advanced to third base on a wild throw. Morrie Rath followed with a single to bring him home with the first run of the game. It was a spectacular day for Eller and it brought him national acclaim. After the game White Sox slugger Joe Jackson said, “How are you going to hit a pitcher with the stuff that fellow had today? I have been batting Walter Johnson all summer, but Walter did not show me any speed like Eller.”38 Reds catcher Bill Rariden said Eller “has more speed by far than any other pitcher in the National League.”39

The Reds needed one more victory to win the best-of-nine Series. In Game Six the Reds took an early 4-0 lead, but the White Sox came back to win the game, 5-4 in 10 innings. Kerr pitched a complete game for the White Sox. Ruether pitched the first five innings for the Reds, and Ring pitched the last five innings. In Game Seven, Cicotte pitched a fine game and the White Sox won 4-1. Sallee allowed four runs on nine hits before departing in the fifth inning.

With the Reds now leading the Series four games to three, Moran turned to Eller to start Game Eight on October 9. Disturbing rumors had been circulating that some “crooked” players on the White Sox had accepted money from gamblers to lose games in the Series. Roush suspected that gamblers had paid his teammates Ruether and Sallee to lose Games Six and Seven.40 Moran questioned Eller before Game Eight: “Did any gamblers offer you money to throw today’s game?” Yes, Eller said, a man offered him $10,000 to lose the game. “What did you tell him?” asked Moran. “I told him to get out of my sight quick, or I’d punch him right square on the nose,” said Eller.41

With 32,930 fans looking on, Eller and Lefty Williams squared off on a windy day in Chicago. In the first inning Williams was replaced by Bill James as the Reds tallied four runs. The White Sox got on the board in the third inning when Jackson hit a solo homer to right field. The Reds continued to hit well, including Eller, who singled in the sixth inning and scored a run. Going into the bottom of the eighth inning, the Reds had 10 runs on 15 hits, and the White Sox had one run on five hits.

The White Sox launched a comeback in the eighth inning. With one out, Collins singled and Buck Weaver doubled. Jackson doubled to right field, driving in two runs. Happy Felsch popped out for the second out, but Gandil tripled to right field, scoring Jackson. Roush misplayed Risberg’s fly ball to center field, permitting Gandil to score, and Schalk grounded out to end the inning. The White Sox clouted pitches from a tired Eller, but it was too little, too late. In the ninth inning, Eller allowed two baserunners but no runs. The final score was 10-5, and the Reds had won their first world championship. Eller threw 130 pitches in the game.42

The Reds players each received $5,207 for winning the Series. This was quite a reward for Eller, whose 1919 salary was about $2,400.43 He returned home to Danville on October 15 and was greeted by an enthusiastic throng and a brass band. After a parade through downtown Danville, he was presented with “the finest piano the market affords” and other gifts from local merchants.44

In November Eller was asked about proposed rule changes in major-league baseball that would ban the shine ball. He said, “I do not care at all what sort of rules they pass. The abolition of the shine ball will not hurt me in the least.”45 Meanwhile, on display in the National League office in New York was a ball thrown by Eller in the World Series. It was plain to see that one side of the ball had been “shined.”46

In February 1920, the major leagues banned “all freak deliveries” including the shine ball, although some spitball pitchers could continue to throw the spitball until they retired.47 Eller tried to make light of the situation. In March he said he was unconcerned about the ban because his shine ball “never accomplished a great deal.”48 Pitching in May, he mixed in some curveballs with his fastball, but it was evident that he was not the same pitcher without his shine ball. Moran used him sporadically out of the bullpen while he worked on pitches to supplement his fastball.

In June Eller met with NL President John Heydler to protest the new rules. Eller claimed he was “improperly and illegally restrained” from earning his livelihood, and he threatened to sue the league.49 “I am forbidden to use my very best skill to earn a living,” he said. “Without the shine ball, I am of no use to the Cincinnati team.”50 An editorial in The Sporting News asserted that “the game cannot be arranged just to suit his style of delivery.”51

In July Eller returned to the starting rotation without his shine ball. He pitched well on July 20 but lost 3-2 to Brooklyn’s Burleigh Grimes (one of the pitchers who were permitted to throw the spitball). Ten days later, Eller shut out Brooklyn and had his best day ever as a batter, with four hits and four RBIs in an 11-0 rout. On August 17 he struck out nine batters in a 3-2 win over the Cubs, and on September 5, he pitched all 12 innings of a 6-4 victory over the Cardinals. Cincinnati and Brooklyn were in a close pennant race until the Reds lost 14 of 17 games in mid-September. Eller finished the 1920 season with a 13-12 record and a 2.95 ERA. He did not dominate hitters as he had done in 1919, but he did pitch respectably.

In 1921 Eller arrived late to spring training and struggled to get into condition. The Reds suspended him on April 22 for failing to get into condition.52 He was reinstated on May 17, but Moran said he would not pitch in a game until he was “in the best of shape.”53 On May 30 Eller made his first appearance of the season, in relief against the Cardinals, and allowed three runs on eight hits in 3⅓ innings. His first start came on June 28 against the Cardinals, but he was quickly removed from the game after giving up two home runs in the first inning. He won two starts in July, despite allowing eight earned runs and nine walks in 14 innings. Those were Eller’s last starts; he spent the rest of the season in the bullpen. On August 11 it was reported that Moran intended to use Eller mainly to pitch batting practice.54 Eller finished the 1921 season with a 2-2 record and a 4.98 ERA in 34⅓ innings, and in December he was traded to the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League. His major-league career was over.

On August 3, 1921, Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis banned eight White Sox players for life for conspiring to throw the 1919 World Series: Cicotte, Felsch, Gandil, Jackson, Fred McMullin, Risberg, Weaver, and Williams. Against Eller in the Series, Weaver had four hits in nine at-bats (a .444 average), but Felsch, Gandil, Jackson, and Risberg combined for only three hits in 29 at-bats (.103). Were these players trying their best? Sadly, the Reds’ world championship, and Eller’s great pitching performances, were tainted.

In 1922 Eller went 6-10 with a 4.67 ERA in 108 innings for Oakland before he was sold in August to the Mobile Bears of the Southern Association. He pitched in four games for Mobile55 and was released.56 Eller then became player-manager of the Mount Sterling (Kentucky) Essex of the Class D Blue Grass League. On September 10, 1922, he gave up seven runs in a game against the Cynthiana (Kentucky) Merchants.57 His descent from World Series heroics to Class D thrashing took less than three years. In 1923 Eller continued as player-manager of Mount Sterling, and in 1924, he pitched 108 innings for the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association. He then retired from professional baseball at the age of 30.

Eller became an Indianapolis policeman in November 192458 and served on the force for 22 years.59 In the 1950s he worked as a truck driver and security guard.60 Stricken with cancer, he died on July 18, 1961, in Indianapolis at the age of 67.

Consider the career trajectories of these National League contemporaries:

- Hod Eller, born in 1894

– 45-26 record and 2.37 ERA in 618 innings before the 1920 season

– denied use of his favorite pitch, the shine ball, in 1920

– out of major-league baseball after the 1921 season - Burleigh Grimes, born in 1893

– 34-39 record and 2.89 ERA in 691 innings before the 1920 season

– permitted to use his favorite pitch, the spitball, until he retired from major-league baseball after the 1934 season

– inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1964

How would Eller’s career have turned out if he were permitted to use his favorite pitch after 1919?

The Jealous Shine Ball

By George Moriarty

Said the Spitter to the Shiner, “I’m the best ball in the game.

Name another slant that’s finer, or can boast of half my fame.

I am speedy, sly, deceiving, and I laugh with fiendish glee

when the sluggers beat it grieving to the bench because of me.

And with three men on the bases, and the pitcher in a fit,

you can just bet twenty cases, I’ll be thrown to stop a hit.

I was used by Walsh and Chesbro – these the greatest of the band.

Coveleskie, too, and Tesreau – all their names immortal stand.”

Said the Shiner to the Spitter, “Why should you rave, rant and snort?

You’re a filthy and unfit ball, yes, the worst ball in the sport.

Though your break is quite contrary, and you swell the strike-out list,

you are far from sanitary, if you’re canned you won’t be missed.

You’re a slimy ball, doggone you! You are wild and reek with sin;

pitchers only spit upon you, and what’s more, they rub it in.”

Said the Shiner to the Spitter, “You forget my pedigree –

you can lamp no home-run hitter when Ed Cicotte pitches me.

I am cleaner, greater, truer; to change places I don’t pine.

I’m a better ball than you are,” to the Spitter said the Shine.61

Notes

1 Fort Wayne (Indiana) Sentinel, September 29, 1917.

2 Ibid.

3 Cincinnati Enquirer, October 19, 1916.

4 Decatur (Illinois) Daily Review, September 23, 1914.

5 Chicago Daily Tribune, April 12, 1916.

6 Muscatine (Iowa) Journal, August 21, 1915.

7 Cincinnati Enquirer, September 8, 1916.

8 Washington Herald, October 7, 1919.

9 Literary Digest, September 18, 1920.

10 Cincinnati Enquirer, October 8, 1917.

11 LaCrosse (Wisconsin) Tribune and Leader Press, August 14, 1918.

12 El Paso (Texas) Herald, November 14, 1919.

13 Des Moines Daily News, August 29, 1917.

14 Kingston (New York) Daily Freeman, December 3, 1917.

15 San Antonio Light, January 13, 1918.

16 Kansas City (Kansas) Star, December 18, 1917.

17 Cincinnati Enquirer, March 9, 1919.

18 Logansport Pharos-Reporter, February 11, 1919.

19 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 12, 1919.

20 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 21, 1919.

21 East Liverpool (Ohio) Evening Review, July 10, 1919.

22 Cincinnati Enquirer, August 8, 1919.

23 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 8, 1919.

24 Hicksville (Ohio) Tribune, August 14, 1919.

25 Portsmouth (Ohio) Daily Times, March 19, 1920.

26 Edd Roush, interviewed by Bob Hunter, Baseball Digest, March 1976.

27 Literary Digest, September 18, 1920. If the shine ball was thrown with the smooth surface on one side, the pitch broke laterally. Eller said he did not use this variation because batters had little trouble hitting it.

28 New York Times, August 16, 1919.

29 Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Evening News, August 20, 1919.

30 Cincinnati Enquirer, August 17, 1919.

31 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 13, 1919.

32 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 25, 1919.

33 Susan Dellinger, Red Legs and Black Sox: Edd Roush and the Untold Story of the 1919 World Series (Cincinnati: Emmis Books, 2006).

34 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 1, 1919.

35 Reading (Pennsylvania) Times, October 7, 1919.

36 The Sporting News, October 9, 1919.

37 Washington Herald, October 7, 1919.

38 Coshocton (Ohio) Tribune, October 7, 1919.

39 Wichita (Kansas) Beacon, October 23, 1919.

40 Susan Dellinger, Red Legs and Black Sox.

41 Ibid.

42 Sandusky (Ohio) Register, October 10, 1919.

43 New Castle (Pennsylvania) Herald, January 8, 1920.

44 Chicago Daily Tribune, October 16, 1919.

45 Cincinnati Enquirer, November 16, 1919.

46 El Paso Herald, November 29, 1919.

47 Washington Herald, February 10, 1920.

48 Portsmouth Daily Times, March 19, 1920.

49 Reading Times, June 12, 1920.

50 Ironwood (Michigan) Daily Globe, June 24, 1920.

51 The Sporting News, June 17, 1920.

52 Kansas City (Missouri) Times, April 23, 1921.

53 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 18, 1921.

54 Portsmouth Daily Times, August 11, 1921.

55 Marshall D. Wright, The Southern Association in Baseball, 1885-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002).

56 Monongahela (Pennsylvania) Daily Republican, October 14, 1922.

57 Cincinnati Enquirer, September 11, 1922.

58 Indianapolis Star, November 6, 1924.

59 Valparaiso (Indiana) Vidette Messenger, November 2, 1946.

60 Indianapolis city directories, 1952, 1955, 1956.

61 Atlanta Constitution, April 22, 1919.

Full Name

Horace Owen Eller

Born

July 5, 1894 at Muncie, IN (USA)

Died

July 18, 1961 at Indianapolis, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.