How Cheap was Charles Comiskey? Salaries and the Black Sox

Editor’s note: This article was presented at the SABR Black Sox Scandal Centennial Symposium on September 28, 2019, in Chicago. It also appears in the SABR Business of Baseball Committee Newsletter, “Outside the Lines,” in Fall 2019.

The story of the infamous Chicago Black Sox is well known, but less well understood. Groundbreaking research over the past two decades has largely debunked many of the myths that grew out of Eliot Asinof’s highly entertaining, if factually challenged, book and subsequent movie, Eight Men Out. Despite the vast quantity of documents and research, the financial side of the story still remains murky in its details. Not so much the bribes that were, or were not, paid or received, but rather the salaries that were paid, the profits that were earned, and the role they played in the decision of the fateful eight to agree to throw the World Series.

The story of the infamous Chicago Black Sox is well known, but less well understood. Groundbreaking research over the past two decades has largely debunked many of the myths that grew out of Eliot Asinof’s highly entertaining, if factually challenged, book and subsequent movie, Eight Men Out. Despite the vast quantity of documents and research, the financial side of the story still remains murky in its details. Not so much the bribes that were, or were not, paid or received, but rather the salaries that were paid, the profits that were earned, and the role they played in the decision of the fateful eight to agree to throw the World Series.

On this, the 100th anniversary of the infamous Black Sox Scandal, we can take stock of all that we have learned and debunked about the scandal that forever changed MLB. While many facts are now clear, thanks to the tireless work of SABR’s Black Sox Scandal Committee as a whole and its members individually (see the suggested reading list at the end of this article), the explanation of why the players acted in the way that they did (or did not, in the case of Buck Weaver) may never be known.

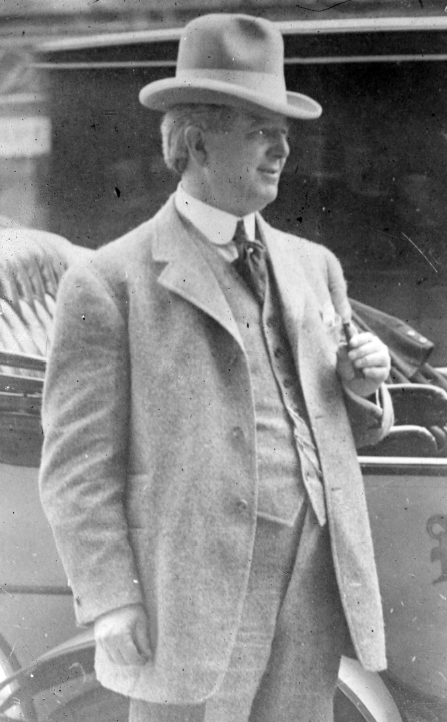

One theory for why the players conspired to throw the World Series is that White Sox owner Charles Comiskey was a cheapskate. While the myth that Comiskey stiffed Eddie Cicotte out of a bonus has been discredited, his reputation as a skinflint is still strong. And for good reason. However, when put into perspective, Comiskey treated his players better than most owners. So while he was cheap relative to today’s standards, he was relatively generous for his day.

The focus of this essay will be on that theory. My ongoing work collecting and collating player salaries from the transaction card database at the National Baseball Library in Cooperstown has yielded hundreds of salary observations from the 1919 season. While the task of collecting these salaries is still a work in progress, sufficient data have been collected to allow for a solid preliminary analysis of team payrolls in 1919. The conclusion that can reasonably be drawn is that Charlie Comiskey was indeed cheap, but no cheaper than any other MLB owner.

There are two issues worth examining. First, the bonus issue. The story, perpetuated by a scene from the movie Eight Men Out, is that Eddie Cicotte had a clause in his contract promising him a bonus for winning 30 games, and that Comiskey conspired to keep him off the mound at the end of the season in order to prevent him from cashing in. There are two problems with this story, making it easy to discredit. The first is the research done by others before me that shows that Cicotte was not denied a chance to win his 30th game. But even more damning evidence comes from Cicotte’s contract, which does not contain any bonus clause whatsoever. Bonus clauses were not common in 1919, so the fact that Cicotte did not have one is certainly not unusual. Out of 226 AL contracts that I have examined, only 19 had a bonus clause.

The transaction card files yield information on the salary and bonus clauses in thousands of player contracts, dating from 1911 into the 1980s. By focusing on the 1919 season we can get a good idea of how well paid the White Sox were relative to other teams. For the purposes of this essay, I am focusing only on the American League, as my work on the National League is incomplete at this time. The salary files are not complete — either because there are missing data or because I have not yet found the contracts for some players. Both issues can be explained briefly.

The transaction card files were obtained by the Hall of Fame library from the American and National League offices of the president when the individual leagues were dissolved and brought under the umbrella of MLB following the 1999 season. That reorganization is the provenance of the files. The files themselves are a set of thousands of index cards. The index cards are organized alphabetically by player name for the American League, and by year and team for the National League. The cards contain all of the non-standard information that appeared on each player’s contract.

All players signed a current form of the standard player contract, which was then forwarded to the league president’s office for approval. The league recorded all of the non-standard information in each contract on index cards that it kept on file. This non-standard information included all of the information that was filled into the blanks on the standard player contract: date, team and player name, and salary amount. It also included any added clauses — e.g. bonus or penalty clauses, and noted any clauses deleted or amended from the standard player contract. The most common instances of such amendments were the elimination of the 10-day clause, which gave the team the right to vacate the contract and all obligations therein with a 10-day notice to the player.

Contract cards exist for many more players than ever appeared in a major-league uniform, because players were often signed to contracts that were not fulfilled. Sometimes this occurred because players retired or were drafted, but more often it occurred because they did not make the major league club out of spring training, and never did appear in a MLB game.

Unfortunately, contract cards do not appear to exist for every player who did appear in a MLB game. At this point it is impossible to say for certain, because I have not yet cataloged every one of the cards, but because they are stored alphabetically, unless some serious alphabetization errors have occurred, players are missing. For example, I have been unable to locate a contract card for Oscar Stanage, who appeared in a total of 1,096 games for the Reds and Tigers in a 14-year career spanning the years 1906 to 1925. Of particular interest for this study is the fact that he appeared in 38 games as a backup catcher and first baseman for the Detroit Tigers in 1919. I have searched all through the “S” boxes for Oscar Stanage, and come up empty. Alphabetization errors are not uncommon (e.g. it would not be unusual to find Stanage misfiled behind Stapleton), and not difficult to overcome if they are misfiled near where they should be, as the Stanage-Stapleton example would suggest. But if there are cards misfiled under the first letter — for example if Stanage was filed under “O” — it would be harder to find.

All of this is in explanation for the lack of complete payroll information for the 1919 season. Baseball-Reference.com lists 282 players as having appeared on AL rosters in 1919. I have been able to find contracts for 226 of these players (80%). However, the players for whom I have found contracts represent a disproportionate share of the playing time (Table 1), indicating that the bulk of the missing players are fringe players who were on the roster for short periods of time. The point here is in defending the team payroll data that I have put together as quite reliable, if not completely accurate. Only New York contracts account for 100% of the roster in 1919, but only Philadelphia contracts account for less than 92% of team innings pitched or plate appearances.

Table 1: Contracts as percentage of PA and IP by team

| Team | PA | IP |

|---|---|---|

| Red Sox | 99% | 100% |

| White Sox | 97% | 100% |

| Indians | 100% | 98% |

| Tigers | 97% | 92% |

| Yankees | 100% | 100% |

| Athletics | 89% | 89% |

| Browns | 98% | 98% |

| Senators | 93% | 96% |

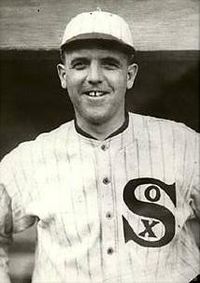

As mentioned earlier, bonus clauses were rare. Barely 8% of the contract cards I have seen for 1919 have bonus clauses, and only one of them played for the White Sox. Lefty Williams, not Eddie Cicotte, had a bonus clause in his contract that would reward him for winning 15 games ($375), and an additional bonus of $500 if he won 20 games. Williams was 23-11 in 1919, thus earning both bonuses.

Without access to the White Sox financial records, we can only assume that Comiskey paid the bonus, though Williams’s implication in the 1919 fix would certainly seem to have warranted a second thought by Comiskey. 1919 was actually an outlier for Comiskey when it came to paying bonuses. While contract cards do not exist for every player for every year, none of those in my database contain bonus clauses for a White Sox player from 1911 (the contract database begins in 1911) through 1918. The first recorded bonus allotted by Comiskey after 1919 was in 1921, when he included a $600 season-ending roster bonus in the contract of the immortal Hal Bubser. Hal did not appear on the White Sox roster until 1922, so he certainly did not earn that 1921 bonus. It wasn’t until the 1930s that Comiskey routinely began to insert bonus clauses in player contracts.

Without access to the White Sox financial records, we can only assume that Comiskey paid the bonus, though Williams’s implication in the 1919 fix would certainly seem to have warranted a second thought by Comiskey. 1919 was actually an outlier for Comiskey when it came to paying bonuses. While contract cards do not exist for every player for every year, none of those in my database contain bonus clauses for a White Sox player from 1911 (the contract database begins in 1911) through 1918. The first recorded bonus allotted by Comiskey after 1919 was in 1921, when he included a $600 season-ending roster bonus in the contract of the immortal Hal Bubser. Hal did not appear on the White Sox roster until 1922, so he certainly did not earn that 1921 bonus. It wasn’t until the 1930s that Comiskey routinely began to insert bonus clauses in player contracts.

The second financial myth I wish to address is that Comiskey drove his players to consort with gamblers because of his penurious nature. The White Sox were a very well paid team (Table 2). In fact, they were the best paid team in the American League. A caveat to the data in Table 2: they are a work in progress. They still need to be adjusted for days on the roster for the many players who came and went during the season. So while these final totals will change, the relative team order is unlikely to be affected.

While Comiskey’s Sox were well paid relative to other teams, that does not mean that Comiskey was generous. Today, it is not uncommon for payroll to exceed 60% of total revenues. In 1919 owners were not so generous — one of the many benefits of the reserve clause. While we don’t have team accounting records for the White Sox for 1919, we do have them for the Yankees, and we know that they paid their players just under 33% of their revenues. This is quite generous compared to the data presented to Congress during the Cellar Anti Monopoly hearings in 1951. Those data are for selected years only. In 1929 MLB teams reported revenues of $11.4 million and player salaries of only $3 million, a measly 26.3%. So while Charlie was cheap, he was no cheaper than any of his contemporaries, all of whom routinely used the reserve clause to exploit player labor for their own profits.

Table 2: 1919 American League Payrolls

| Team | Payroll | Avg player |

|---|---|---|

| White Sox | $111,397 | $3,713 |

| Indians | $101,142 | $3,612 |

| Red Sox | $100,640 | $3,355 |

| Yankees | $100,408 | $3,347 |

| Senators | $85,230 | $3,157 |

| Tigers | $83,365 | $3,789 |

| Browns | $77,935 | $2,783 |

| Athletics | $57,340 | $2,124 |

| AVG | $89,682 | $3,235 |

The White Sox 1919 payroll was disproportionately allocated, with the top three players earning $29,333 (26%) of the total payroll (Table 3). Not only was Charlie not cheap overall, he was quite generous on an individual basis. White Sox players were among the highest paid at their positions, leading the league at second base (Collins), and catcher (Schalk). Buck Weaver was the second highest paid third baseman, behind only Home Run Baker ($12,000), and Shoeless Joe Jackson was fifth among outfielders, behind Cobb, Speaker, Ruth, and Harry Hooper.

Depending on whether one considers Ruth an outfielder or a pitcher, it was either Ruth ($10,000) or Walter Johnson ($9,500) who led all AL pitchers in salary, and Eddie Cicotte, the highest paid hurler for the Sox, was either the 7th or 8th best paid pitcher. Red Faber and Erskine Mayer also cracked the top 15. Overall, Eddie Collins was second only to Ty Cobb’s $20,000 salary in all of MLB (Table 4).

Table 3: White Sox Player Salaries 1919

| Pos | Player | Salary |

|---|---|---|

| C | Ray Schalk | $8,094 |

| 1B | Chick Gandil | $4,000 |

| 2B | Eddie Collins | $15,000 |

| SS | Swede Risberg | $3,250 |

| 3B | Buck Weaver | $7,250 |

| OF | Nemo Leibold | $3,000 |

| OF | Joe Jackson | $6,000 |

| OF | Happy Felsch | $4,287 |

| IF | Fred McMullin | $3,000 |

| OF | Shano Collins | $3,000 |

| C | Byrd Lynn | $2,100 |

| OF | Eddie Murphy | $3,000 |

| C | Joe Jenkins | $2,100 |

| IF | Hervey McClellan | $1,500 |

| P | Eddie Cicotte | $5,115 |

| P | Lefty Williams | $3,000 |

| P | Red Faber | $4,571 |

| P | Grover Lowdermilk* | $3,300 |

| P | Dickey Kerr | $2,400 |

| P | Dave Danforth | $3,000 |

| P | Bill James* | $2,700 |

| P | Frank Shellenback | $2,500 |

| P | Erskine Mayer | $4,200 |

| P | Roy Wilkinson | $2,700 |

| P | John Sullivan | $2,550 |

| P | Win Noyes | $2,100 |

| P | Tom McGuire | N/A |

| P | Charlie Robertson | $1,500 |

| P | Joe Benz | $3,000 |

| P | Pat Ragan | $3,000 |

| P | Reb Russell | $3,000 |

*played on multiple teams

Table 4: Baseball’s Biggest Paychecks 1919

| Player | Team | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Ty Cobb | Tigers | $20,000 |

| Eddie Collins | White Sox | $15,000 |

| Tris Speaker | Indians | $13,125 |

| Frank Baker | Yankees | $11,583 |

| Babe Ruth | Red Sox | $10,000 |

| Buck Herzog | Braves/Cubs | $10,000 |

| Grover Alexander | Cubs | $9,975 |

| Walter Johnson | Senators | $9,500 |

| Harry Hooper | Red Sox | $9,000 |

| Carl Mays | Red Sox/Yankees | $8,000 |

It is worth comparing baseball salaries to those earned by other entertainers and average Americans in order to put them into perspective. The average MLB salary in 1919 was $3423. The average Sox player earned $3713. As we already know, the Sox were an above average team both on the field and in payroll.

Another segment of the entertainment industry that was subject to a reserve clause was the movie industry. Unlike baseball, Hollywood first breached the reserve clause with the founding of United Artists Studio in February of 1919. Salaries for top actors easily eclipsed those of the top earning ballplayers. Mary Pickford, one of the founders of United Artists and the queen of the silver screen, was earning $10,000 per week. Hollywood’s queen was the king of entertainers.

Another segment of the entertainment industry that was subject to a reserve clause was the movie industry. Unlike baseball, Hollywood first breached the reserve clause with the founding of United Artists Studio in February of 1919. Salaries for top actors easily eclipsed those of the top earning ballplayers. Mary Pickford, one of the founders of United Artists and the queen of the silver screen, was earning $10,000 per week. Hollywood’s queen was the king of entertainers.

The average annual US manufacturing wage in 1919 was $860. This is a reasonable wage with which to compare ballplayers, since most of them had little education, and often worked work blue collar jobs when they no longer played baseball. Even that sounds generous compared to the average Negro League ballplayer, who was bringing in $304.50. Race based wage data are scarce before WWII, but what little we do know suggests the average African American worker was bringing home $554 in 1919, so a Negro League salary, earned over a six month season, was pretty good pay relative to other African Americans. Despite the reserve clause, being a ballplayer was a good job. The pay was much better than what an average American earned, and it only required six months work to earn it.

Ballplayers, regardless of their race, were well paid. White ballplayers did especially well, earning more than four times the average annual US manufacturing wage. And the White Sox were the best paid of those ballplayers, but not nearly as well paid as their rival entertainers in Hollywood. All of which does little to help us explain why eight well paid ballplayers would risk their livelihoods to throw a World Series, which, had they won, would have netted full shares of $5207, more than doubling the salaries of Cicotte and Williams, and nearly doubling Shoeless Joe’s salary.

Whatever the motivation, being underpaid seems a weak explanation. The White Sox were not underpaid relative to other ballplayers. And if it was a general gripe of ballplayers, who were certainly underpaid as a profession (relative to the revenues they generated), why didn’t they try to throw the World Series earlier and more often? The payroll gripes were neither unique to the White Sox in 1919, nor were they unvoiced in prior years. The 1919 World Series, after 100 years, is still intriguing, both for reasons we know, and may never know.

MICHAEL HAUPERT is Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and co-chair of the SABR Business of Baseball Committee.

Further Reading

Asinof, Eliot, Eight Men Out: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series, New York: Henry Holt, 1963.

Carney, Gene, Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

Carney, Gene, “Eddie Cicotte on the Day that Shook Baseball,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Fall 2009): 99-103.

Dellinger, Susan, Red Legs and Black Sox: Edd Roush and the Untold Story of the 1919 World Series, Cincinnati: Emmis Books, 2006.

“Eight Myths Out: The Black Sox Scandal,” Society for American Baseball Research, https://sabr.org/eight-myths-out.

Ferber, Bill, Under Pallor, Under Shadow: The 1920 American League Pennant Race that Rattled and Rebuilt Baseball, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011.

Fountain, Charles, The Betrayal: the 1919 World Series and the Birth of Modern Baseball, New York: Prentice Hall, 2016.

Ginsburg, Daniel, The Fix is in: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2004.

Goldfarb, Irv, “Charles Comiskey,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/8fbc6b31.

Hoie, Bob, “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox,” Base Ball a Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Spring 2012): 17-34.

Hornbaker, Tim, Turning the Black Sox White: the Misunderstood Legacy of Charles A. Comiskey, New York: Sports Publishing LLC, 2014.

Lamb, William F., Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2013.

Nathan, Daniel A., Saying It’s So: A Cultural History of the Black Sox Scandal, Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2003.

Pomrenke, Jacob, ed., Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox, Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2015.

The Inside Game: The Official Newsletter of SABR’s Deadball Era Committee: Special Black Sox Issue, Vol. XIX, No. 3 (June 2019).

Thorn, John, “Baseball’s Bans and Blacklists: The Complete Story,” Our Game, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/baseballs-bans-and-blacklists-5182f08d43ff.