Boston Unions team ownership history

This article was written by Charlie Bevis

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

The Boston Unions were one of the few ballclubs to complete the entire 1884 season of the Union Association in its sole year as a major league.

The Union Athletic Exhibition Company (UAEC) owned the ballclub, which was admitted to the Union Association on March 17, 1884.1 The UAEC was formed a week later, on March 26, with Frank Winslow as president, Frank Mullen as secretary, and treasurer, and Daniel Knowlton and George Wright joining them as directors.2 The UAEC was a stock company, which sought to raise $25,000 by selling shares at $100 each.3

The Union Athletic Exhibition Company (UAEC) owned the ballclub, which was admitted to the Union Association on March 17, 1884.1 The UAEC was formed a week later, on March 26, with Frank Winslow as president, Frank Mullen as secretary, and treasurer, and Daniel Knowlton and George Wright joining them as directors.2 The UAEC was a stock company, which sought to raise $25,000 by selling shares at $100 each.3

The baseball club was a secondary interest of the UAEC, whose primary business was staging a wide variety of athletic events at the Dartmouth Street Grounds, a grandstand and bleachers built on an odd-shaped lot leased by the UAEC.4 Bicycle racing was the company’s primary interest, with ancillary interests in running competitions (some at night under artificial lighting), wrestling matches, and anything that would attract paying customers to the grounds.5 Winslow created the UAEC to supplement his wintertime business, an indoor roller-skating rink, with an outdoor sporting venue that would provide year-round entertainment for Boston residents.

Winslow, as president of the UAEC, is sometimes listed in modern-day baseball encyclopedias as the owner or president of the Boston Unions.6 However, this designation overstates his role in the operation of the ballclub, which was largely attending a few league meetings.7

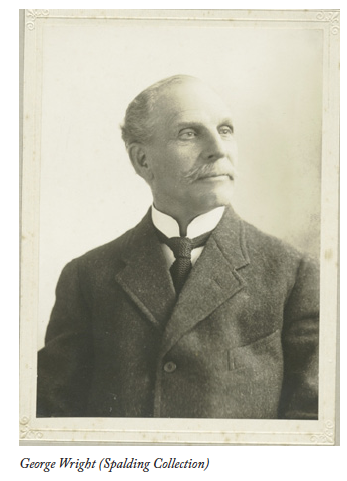

Wright, a former player who operated the Wright & Ditson sporting-goods company, was the primary force behind the baseball operation. He should be considered the de facto president or owner of the Boston Unions rather than Winslow. Wright represented the formative ballclub at early Union Association meetings and was the club’s sole representative at the March 1884 meeting when Boston was admitted to the league.

Wright’s position as head of the Boston Unions is supported by nineteenth-century reporting as well as modern-day analysis. “George Wright will have the supervision of all matters relating to the [Boston] nine,” the New York Clipper reported in April 1884.8 A few years later, George Tuohey wrote that the Boston Unions were “under the management and control of George Wright, T.H. Murnane and Frank Winslow,” presumably listed in order of importance.9 In their 1992 book, economists James Quirk and Rodney Fort described the ownership of the Boston Unions as being a “syndicate headed by George Wright.”10

Wright’s motivation to establish the Boston Unions was not to expand the mission of the UAEC but more personal, to expand his sporting-goods business. Because the Boston club was the eighth one admitted to the Union Association (which the league desperately needed to balance out its schedule), Wright reportedly bargained to operate a ballclub in Boston in exchange for a contract for Wright & Ditson to provide the official baseball of the league.11 Wright was executing a common branding strategy of the era, “acquiring the rights to supply a top league with the ‘official’ ball.”12

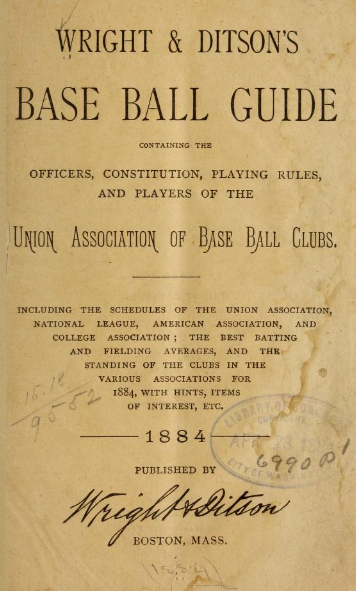

Wright’s company also published the official guide for the Union Association. The Wright & Ditson’s Base Ball Guide provides another apt description of the ownership structure of the Boston Unions (as distinguished from that of the UAEC). In the “Officers and Players” section, the Guide has a blank space following the positions of president and secretary of the Boston club and lists the club’s only representative as being Tim Murnane, the field manager.13

Wright’s company also published the official guide for the Union Association. The Wright & Ditson’s Base Ball Guide provides another apt description of the ownership structure of the Boston Unions (as distinguished from that of the UAEC). In the “Officers and Players” section, the Guide has a blank space following the positions of president and secretary of the Boston club and lists the club’s only representative as being Tim Murnane, the field manager.13

The primary business strategy of the Boston Unions was to charge 25 cents for admission, half the fare charged by the rival National League team in Boston. However, this lower admission price failed to attract many customers. Home attendance for the Boston Unions was a skimpy 28,000 people for the entire 109-game 1884 season, one-fifth of the 146,000 people who attended games at the National League ballpark that season.

While there were no financial results published, the baseball club within the UAEC no doubt lost money. The most definitive piece of evidence is Winslow’s obituary, which stated that the Boston Unions ballclub “was not a financial success.”14 Economic historians believe no Union Association club made a profit and that the average loss for a club in the league was $15,000.15 The Boston Unions dissolved in the late fall of 1884, when the ballclub was evicted from the Union Association after it did not attend the mid-December league meeting to plan for an 1885 season.16

The deceased 10-month-old ballclub proved useful, though, in propelling forward the successful sports-oriented business careers of both Wright and Winslow. Wright & Ditson prospered as a sporting-goods company well into the 1890s.17 For Winslow, the UAEC served to complete a year-round amusement business into 1888, while Winslow’s roller-skating rink remained open until 1892.18

CHARLIE BEVIS is the author of seven books on baseball history, most recently “Red Sox vs. Braves in Boston: The Battle for Fans’ Hearts, 1901-1952” (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017). A member of SABR since 1984, he has contributed more than five dozen biographies to the SABR BioProject as well as several to SABR books. He is an adjunct professor of English at Rivier University in Nashua, New Hampshire.

Notes

1 “The Union Base Ball Club of This City Admitted to the Union Association,” Boston Globe, March 18, 1884.

2 “Organization of the Union Athletic Exhibition Company,” Boston Globe, March 27, 1884; “Boston Gossip,” New York Clipper, April 5, 1884.

3 “Progress and Prospects for the Union League Team,” Boston Globe, March 23, 1884.

4 “The Union Grounds: Plans for the New Athletic Park Completed,” Boston Globe, April 3, 1884.

5 The primacy of bicycle racing is seen by the grandstand being located closer to the bicycle track than to the baseball diamond, with the track bifurcating left field. Additionally, initial stock subscribers included the bicycle manufacturers Pope and Cunningham (“A New Club in Boston,” New York Clipper, March 29, 1884). Winslow was in the process of organizing the UAEC, and had secured the lease for the grounds, when Wright approached him about putting the Boston Unions under the UAEC umbrella (“Boston’s New Nine,” Boston Globe, March 9, 1884).

6 “Owner and Executive Roster,” Total Baseball: The Official Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball, 7th edition (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001), 2460.

7 “Base Ball Business,” Boston Globe, July 2, 1884; “A Special Meeting,” New York Clipper, September 27, 1884.

8 “Boston Gossip,” New York Clipper, April 5, 1884.

9 George Tuohey, A History of the Boston Base Ball Club (Boston: M.F. Quinn, 1897), 83.

10 James Quirk and Rodney Fort, Pay Dirt: The Business of Professional Sports (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 387.

11 Jerry Jaye Wright, “What’s in a Name? George Wright’s Influence, Favors and Deals During the Organization of the Boston Unions of 1884,” North American Society for Sport History, 1990; “The Union Association,” New York Clipper, March 22, 1884.

12 Stephen Hardy, “‘Adopted by All the Leading Clubs’: Sporting Goods and the Shaping of Leisure, 1800-1900,” in Richard Butsch, ed., For Fun and Profit: The Transformation of Leisure into Consumption (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990), 83.

13 Wright & Ditson’s Base Ball Guide; Containing the Officers, Constitution, Playing Rules, and Players of the Union Association of Base Ball Clubs (Boston: Wright & Ditson, 1884), 48.

14 “Frank H. [sic] Winslow Is Dead,” Boston Globe, June 13, 1905.

15 Quirk and Fort, Pay Dirt, 305.

16 “Four Clubs Apply,” Boston Globe, December 19, 1884. The Union Association went out of business in January 1885 when its best team, the St. Louis Maroons, joined the National League.

17 Hardy, “‘Adopted by All the Leading Clubs,’” 87.

18 “Frank H. [sic] Winslow Is Dead.” Boston Globe, June 13, 1905.