The History and Future of the Amateur Draft

This article was written by John Manuel

This article was published in Summer 2010 Baseball Research Journal

The 2010 draft was broadcast nationally in prime time, the third year in a row that Major League Baseball had put its draft on TV. Its top talent, Las Vegas sensation Bryce Harper, was on the cover of Sports Illustrated when he was just sixteen. As that draft approached, the star of the 2009 draft, Stephen Strasburg, was cruising through the minor leagues less than a year after being picked first overall out of San Diego State.

The idea that the draft could generate so much attention was preposterous as recently as 1998. That was the first year that MLB even dared to release its draft list to the public the day the draft finished.

I covered my first draft for Baseball America in 1997, as a truly peripheral part of the magazine’s coverage. I remember vividly how Allan Simpson—BA’s founding editor and the man who essentially invented coverage of the baseball draft—had white boards in his office, tracking the draft round by round. He’d get calls from scouts, college coaches, agents—even sometimes from clubs—with information about what players were picked where. He wrote them, almost always in pencil, it seemed, on his white boards, three years before Tim Russert and Florida and the 2000 Election made similar but smaller white boards immortal.

We were the only complete source for this information. The next year we announced we’d be selling our draft lists and could fax them for the grand fee of $— to anyone interested. Within a week of our announcement, MLB announced it would release its list. We still made enough money off the “Draft Deluxe” offer to buy new desktop computers.

Interest in the draft doesn’t always go hand in hand with knowledge about the draft. Technically the proceedings are spelled out in Rule 4 of MLB’s Professional Baseball Agreement—just ahead of the section on the Rule 5 draft—but most people call it the June draft or the amateur draft. Technically, its name is the First-Year Player Draft.

That change was made in the late 1990s, to close a draft loophole and to keep amateurs from becoming free agents. The draft itself, from its inception in 1965 to the present, always has been a reaction to the way major-league clubs procure amateur talent. That’s its past history, and it appears to be its future as well.

The draft was a new concept only to baseball. It came to football first (1936), and the two other major professional leagues in basketball (1947) and hockey (1963) already had followed suit by 1964, when baseball decided to act. In 1964, led by the $205,000 bonus the Angels gave to Wisconsin outfielder Rick Reichardt, major-league clubs paid more than $7 million to amateur players—more than was spent on major-league salaries.

Before the draft, procuring talent was on a first-come, first-served basis. Scouts scoured the country, going to games, getting to know players’ families and competing with each other to cultivate the best relationship, make the best offer, and sell their organization as the most attractive one for an up-and-coming ballplayer. Not surprisingly, the system tended to reinforce competitive imbalance. The Cardinals, Yankees and other clubs that had extensive scouting networks for amateurs and that recognized the value of player development in their minor-league systems thrived; those clubs that didn’t, such as the postwar Cubs, Indians, and Athletics, were mired in the second division in what seemed to be perpetuity.

The draft helped change that, giving the worst teams a shot at the best talent. The A’s drafted Rick Monday first overall in 1965 and five rounds later took another Arizona State Sun Devil, Sal Bando. Later, with their twentieth selection, they drafted and signed Ohio prep shortstop Gene Tenace. Only a year later, drafted second overall, Reggie Jackson (yet another Sun Devil) joined the organization, and in 1967 the A’s took Vida Blue, in the second round, out of a Louisiana high school. The foundations of their early 1970s dynasty were laid in those first few draft classes.

The draft helped change that, giving the worst teams a shot at the best talent. The A’s drafted Rick Monday first overall in 1965 and five rounds later took another Arizona State Sun Devil, Sal Bando. Later, with their twentieth selection, they drafted and signed Ohio prep shortstop Gene Tenace. Only a year later, drafted second overall, Reggie Jackson (yet another Sun Devil) joined the organization, and in 1967 the A’s took Vida Blue, in the second round, out of a Louisiana high school. The foundations of their early 1970s dynasty were laid in those first few draft classes.

Of course MLB wasn’t installing a draft out of egalitarian dreams; it wanted to cut those signing bonuses, and the way to do it was to give amateur players one club to negotiate with, instead of twenty. In that, the draft worked exceedingly well. Monday, the draft’s first number-one overall pick, got a $100,000 bonus, or less than half of what Reichardt had received as a free agent in 1964. Monday’s bonus record lasted until 1975 (Danny Goodwin, Angels, $125,000), and Reichardt’s pre-draft record wasn’t broken until 1979. That record—a $208,000 bonus for Yankees draftee Todd Demeter—wasn’t even publicly known until 25 years later. A second-round pick, Demeter hit just .173 in a 34-game trial in Double A.

Baseball kept bonuses down, no matter who the players were or how talented they were. Scouts universally lauded Darryl Strawberry as the best talent out of Los Angeles in years, and the Mets gave him a $200,000 bonus in 1980, still short of Reichardt’s mark. None of the celebrated members of the 1984 Olympic baseball team broke the record—not Mark McGwire, not Will Clark.

The business of holding the line on bonuses began to lead to an influx of talent to college baseball, as players who turned down what they thought were insufficient offers out of high school found their way to NCAA play. It led to a golden era for college baseball. Roger Clemens led Texas to the 1983 national championship, two years after the Mets drafted him in the twelfth round out of San Jacinto (Texas) Junior College. Instead of signing him, the Mets faced Clemens twice in the 1986 World Series with Boston. The Giants could have had Barry Bonds out of high school, in 1982, but a difference of less than $10,000 in negotiations prompted Bonds to attend Arizona State. The Pirates got him with the sixth overall pick three years later.

On and on it went. In 1987, Ken Griffey Jr. brought obvious talent and a big-league bloodline to become one of the most celebrated number-one overall picks ever. Still, the Mariners gave him a bonus of just $160,000.

Only Bo Jackson, as Heisman Trophy winner with an NFL future, could get more money out of a major league club, after 22 years, than Reichardt. The Royals spent a fourth-round pick on Jackson and then bought him away from football (temporarily) with a major league contract worth $1,066,000, with $100,000 as a signing bonus.

The bonus record wasn’t broken again until 1988, when the Padres signed right-hander Andy Benes for $235,000. Two high-school pitchers, Steve Avery (Braves, $211,000) and Reid Cornelius (Expos, $225,000) signed for bonuses that exceeded Reichardt’s old mark.

In 1989 bonuses started to climb to the point that current-day fans have become accustomed to when the Orioles and number-one overall pick Ben McDonald of Louisiana State reached an impasse. The Orioles finally relented and signed McDonald for an $825,000 major-league deal with a $350,000 bonus, a record broken days later by John Olerud. The Blue Jays signed their third-round pick Olerud for a major-league deal with a $575,000 bonus.

That began the draft’s Common Era, for teams now truly started to take signing-bonus demands into account. In 1990, Texas prep right-hander Todd Van Poppel was the consensus top talent available, and the Atlanta Braves held the first pick. The Braves at that time wanted Van Poppel but decided they couldn’t meet his perceived demands or dissuade him from his commitment to the University of Texas. Instead they chose Florida prep shortstop Larry Wayne Jones of Jacksonvile, whom everyone already called Chipper.

Van Poppel, though, signed with Oakland for a $500,000 bonus and a major-league contract with value of $1.2 million overall. He wound up with a journeyman career, while Jones has an MVP Award and more than 400 home runs while helping give the Braves one of the longest runs of success in team sports history.

Van Poppel’s contract set the stage for 1991, when the Yankees held the number-one overall pick for the second time ever. They drafted North Carolina prep lefthander Brien Taylor and then shattered the bonus record by giving him a $1.55-million straight bonus. That was more than any of the big-league contracts up to that point and almost three times Olerud’s bonus mark.

How much were bonuses increasing overall? In 1990, just three years after Griffey and his $160,000 bonus, every first-round pick signed for at least $175,000. Bonuses continued to climb until 1996, when all hell broke loose, at least in terms of the draft. Because of violations to Rule 4(E) of the Professional Baseball Agreement, which required that teams make a formal contract offer to every pick within fifteen days of the draft, MLB had to grant several top talents free agency.

How much were bonuses increasing overall? In 1990, just three years after Griffey and his $160,000 bonus, every first-round pick signed for at least $175,000. Bonuses continued to climb until 1996, when all hell broke loose, at least in terms of the draft. Because of violations to Rule 4(E) of the Professional Baseball Agreement, which required that teams make a formal contract offer to every pick within fifteen days of the draft, MLB had to grant several top talents free agency.

While three of the players—pitchers Braden Looper and Eric Milton and catcher A. J. Hinch—ended up signing with the teams that drafted them while MLB mulled its options, four others were set free. The loophole free agents included San Diego State first baseman Travis Lee, completing a stint with the Olympic team, and high-school pitchers Matt White, John Patterson, and Bobby Seay. Lee had been the number-two overall pick in the draft, while White (number 7) ranked as the top high-school pitching talent. Patterson (number 5) and Seay (number 12) were consensus first-round talents as well.

The 1996 draft also was the first for the expansion Arizona Diamondbacks and Tampa Bay Devil Rays, who were eager to establish an identity and didn’t even have to field major-league clubs until 1998. The confluence of free agency and new teams created the perfect storm, as Lee signed first for a $10-million contract with the Diamondbacks. White, signing with Tampa Bay, then topped him with a $10.2-million bonus, while Patterson (Diamondbacks, $6.075 million) and Seay ($3 million, Rays) followed with their own mega-deals. In comparison, the number-one overall pick that year, Kris Benson, signed for $2 million.

Only White never reached the majors, but neither Lee, Seay nor Patterson had any lasting big-league impact. White reached Triple A and hurt his shoulder while trying to make the final 2000 Olympic-team roster.

“I can’t imagine what it would be like now with the media attention and the interest there is now in the draft,” said White, a volunteer assistant coach at Georgia Tech in 2010 and hired in June 2010 as pitching coach at the University of Michigan. “I heard my share of criticism for how my career turned out, but I’m sure it would have been greater with the amount of attention the draft receives now.”1

The next year, the Boras Corp. represented Florida State outfielder J.D. Drew, who put together the first (and so far only) 30-homer, 30-steals season in NCAA Division I history. Drew wasn’t going to use Benson’s $2-million bonus as a benchmark; he was using the numbers the loophole free agents got. But when the Phillies took him second overall, they were using Benson’s number. Acrimonious negotiations followed that never came close to bridging the near-$7 million gap between the two sides.

Drew wound up blazing a trail to the draft through independent leagues; at first, Boras hoped this would make Drew a free agent. MLB closed that loophole by renaming the proceedings the First-Year Player Draft, making independent leaguers such as Drew subject to the draft. Drew was part of the 1998 draft and was picked fifth overall this time, by the Cardinals. Eventually, he signed a $7-million big-league contract with a $3-million bonus, which was soon surpassed by that of 1998’s number-one overall pick, Pat Burrell of the University of Miami. He signed with—you guessed it—the Phillies, for a $3.15-million bonus and an $8-million contract.

“Baseball has made an admission that they’re not paying for talent,” Boras later said. “They’re paying for jurisdiction. That’s where the draft is wrong.”

By 1999, it was noteworthy when a first-round pick didn’t receive a $1-million signing bonus. (The only such pick in 1999 was Blue Jays’ first-rounder Alex Rios out of Puerto Rico.) From 1989 through 1999, the average payout for first-round picks increased from $176,000 to about $1.81 million.

Money has continued to be one of the biggest themes of the draft in the 2000s, but the money isn’t what gets all the attention anymore. Now, it’s the talent, as fans and baseball media have started to tune into the draft as never before. Major League Baseball’s past secrecy was a major reason that media rarely gave the draft much attention—MLB didn’t want any. It contended that more draft coverage drove up signing bonuses, and didn’t publicize the draft list in part to keep colleges from going out and recruiting drafted players.

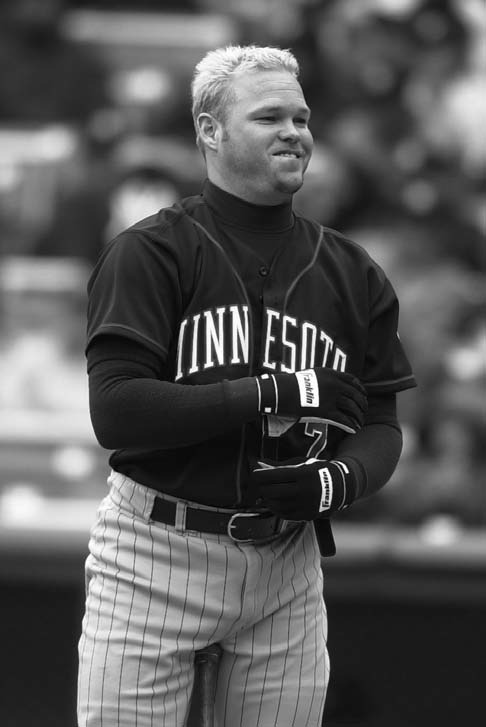

But toward the end of the decade, MLB began to realize that times were changing. In 1998, it actually released its draft list, and it didn’t change its mind. The explosion of new media prompted more changes and openness. In 2001, Southern California ace righthander Mark Prior brought the draft more attention with a remarkable season and awkward pre-draft negotiations with the Twins, who had the number-one overall pick. The NCAA ended up questioning him about his eligibility the night before his College World Series start and after the Twins, citing Prior’s perceived bonus demands, passed over him. Instead, they went for hometown talent Joe Mauer, an athletic catcher who had a Florida State football scholarship waiting for him.

Mauer signed for $5.15 million, which by this time wasn’t even a record—the White Sox had given outfielder (and Stanford quarterback) Joe Borchard $5.3 million the year before. But Prior, picked second overall by the Cubs, received more than twice that amount, signing a $10.5-million major-league contract with a $4-million bonus.

In 2002, MLB puts its draft on public display for the first time, as MLB Radio on MLB.com broadcast the proceedings. It was raw—just the conference call from New York and the thirty clubs on the phone, drafting away. (This writer and Baseball America colleague Will Lingo co-hosted the proceedings.)

In 2007, the draft finally left its conference-call roots behind. ESPN joined with MLB to broadcast the draft from Disney’s Wide World of Sports in Orlando with a 2 P.M. broadcast. There were even three players on hand for the show, led by the third overall selection, Josh Vitters. The players followed their counterparts in other sports, posing for photos with the commissioner.

“It’s a great day for us, and this is such an important day,” Commissioner Bud Selig said. “This is a special event, and we want to communicate that as best as possible to all of our fans. This is really a dramatic manifestation of how the sport has improved. This will get bigger and bigger.”2

In terms of attention and money, it certainly has. Strasburg was the draft’s biggest star in 2009, as he surpassed Prior in many ways, going first overall to the beleaguered Nationals. He wound up signing a major league contract worth more than $15 million with a $7.5-million bonus, giving him both the largest contract in draft history and the largest bonus for a player who signed with the team that drafted him.

All along, MLB has attempted to keep bonuses from spiraling out of control, even as they surge ever higher. Several times, MLB unilaterally has passed sweeping (or at times minor) changes in draft rules, only to have them struck down when challenged because the changes were not collectively bargained. While the Players Association does not represent amateurs, draft picks are tied to free-agent compensation, and the union has argued successfully that, in essence, this makes the draft its business.

Because both sides have had bigger issues to deal with, the draft has never become a focal point of negotiations for a collective bargaining agreement. Instead, MLB has moved toward its recommended bonus slots, first begun in 2000, when Sandy Alderson was MLB’s executive vice president for baseball operations. Alderson gathered scouting directors for what MLB termed “negotiating training,” and the commissioner’s office began recommending signing bonuses for players chosen in the first three rounds. They also forced scouting directors to report above-slot bonus agreements to the commissioner’s office, essentially submitting them for approval.

Because both sides have had bigger issues to deal with, the draft has never become a focal point of negotiations for a collective bargaining agreement. Instead, MLB has moved toward its recommended bonus slots, first begun in 2000, when Sandy Alderson was MLB’s executive vice president for baseball operations. Alderson gathered scouting directors for what MLB termed “negotiating training,” and the commissioner’s office began recommending signing bonuses for players chosen in the first three rounds. They also forced scouting directors to report above-slot bonus agreements to the commissioner’s office, essentially submitting them for approval.

Eventually, MLB expanded the slots to the first five rounds, with the bottom slot of the fifth round extending out as a perceived slot maximum for the rest of the draft. Clubs are subject to fines only if they pay “over slot” without notifying MLB. Other efforts to rein in bonuses included the 2007 introduction of a signing deadline. Previously, players could negotiate until they attended college classes, with no uniform date. Players who had exhausted their college eligibility, or who renounced their eligibility (a new Boras Corp. strategy), could hold out all fall, winter, and spring, right up until a week before the next draft. (Jered Weaver and Stephen Drew, two of the top talents in the 2004 draft, both went that route, signing with the Angels and Diamondbacks, respectively, just before the beginning of the one-week “closed period” in 2005.)

So for 2007, MLB set August 15 as a uniform signing date. The idea was that less time to negotiate gave the teams more leverage over players and their agents. The decision also killed the draft-and-follow process, a system whereby teams could draft high-school or junior-college players, “follow” them through the next season, and then sign them (or not) before the next draft.

Despite the changes, the 2007 draft brought more giant contracts, such as the $7-million major-league contract the Tigers gave to New Jersey prep right-hander Rick Porcello. It tied Josh Beckett’s 1999 deal for the highest amount ever given to a prep pitcher. The Yankees then gave out the biggest contract in draft history pre-Strasburg, to right-hander Andrew Brackman, a 6-foot-10 North Carolina State product. Brackman, who also played two seasons of ACC basketball and had NBA potential thanks to his size, signed for a $3.35-million bonus as part of a major-league contract with roster bonuses that would guarantee Brackman $13 million as long as he didn’t jump to basketball.

The slotting system was still in place as the 2010 draft approached. However, during its ten-year run, MLB and the union have had two CBA negotiations pass peacefully, with no work stoppage. With the 2012 CBA negotiations fast approaching and the sport’s fiscal health looking relatively strong, the draft looms as one of the more important issues of the next CBA.

Scouting directors are loath to speculate on the record about the draft’s future, and they don’t often agree on the changes they’d like to see. The repeated scandals in Latin American player procurement—from age changes to bonus skimming by agents and club officials—have brought calls for an international draft, or for international players to be incorporated into the current First-Year Player Draft. (It’s happened before, as bonus escalation in Puerto Rico prompted MLB in 1989 to make players from the island commonwealth subject to the draft.)

Other proposals for changes to the draft include the formalization of draft slots, making them “hard,“ as is the case with the NBA’s draft contracts; a significant reduction in rounds from the current maximum of fifty; the ability of clubs to trade draft picks; and overall caps on spending for organizations on scouting and player development together, a salary cap for everything not including major-league salary.

“[The draft] is an area that will be of great interest in the next round of negotiations,” Rob Manfred, baseball’s executive vice president for labor relations, told the New York Times in 2009. “I’m not going to speculate as to what our proposals are going to be the next time around, but I will say the purpose of the draft is to make sure the weakest team gets the best player.”3

Of course, that’s only one point of the draft. The other always has been to keep the amount the clubs have to pay players as low as possible.

More telling perhaps than the effort to divine future CBA negotiations are the other trends that are shaping up around the draft. MLB has started operating, on a limited basis, some of its own showcase events, tournaments, or all-star games that gather amateur players in one place for teams to scout.

Agents would resist, but eventually some of these events—USA Baseball’s Tournament of Stars, perhaps—will evolve into a scouting combine, similar to the NFL’s combine. MLB could use such a combine for medical evaluations (such as standard eye exams), for drug testing (currently 200 players MLB deems “top prospects” are drug-tested around the country), and of course for evaluating players’ physical talent.

The overall thrust appears to be an attempt by MLB and its clubs to get more control over the draft in all phases. Every attempt in the past—to control players, to control bonuses—has had unintended consequences, because, when push comes to shove, teams need talent, and players are the ones who provide it. Because it costs so much more to pay established big-leaguers rather than less experienced ones who aren’t arbitration-eligible, it still makes financial sense for a club to pay a sizable, market bonus to a player it wants and to get him under control for the early part of his career. Even if it means going above slot.

JOHN MANUEL is co-editor of Baseball America, where he has worked since September 1996. He has covered everything at the magazine and website from college baseball and prospect rankings to the Olympics and the draft.

BEST DRAFTS EVER

By the Baseball America staff

1. DODGERS 1968

The best, and it’s not really close. The Dodgers assembled an amazing collection of stars as well as solid big-leaguers, with a total of fifteen players who at least made appearances in the majors. Davey Lopes (second round) from the January secondary phase, Bill Buckner (second) from the June regular phase, and Steve Garvey (first) and Ron Cey (third) from the June secondary phase were the stars, but longtime big-leaguers like Tom Paciorek, Joe Ferguson, Doyle Alexander, Geoff Zahn, and Bobby Valentine were also part of the haul.

2. TIGERS 1976

Like the 1968 Dodgers class, the Tigers set themselves apart with quality and quantity. Alan Trammell (second round), Dan Petry (fourth), and Jack Morris (fifth) formed the heart of Detroit’s 1984 World Series champions, and January first-rounder Steve Kemp also had a nice career. Even the best drafts have players who got away, though: Seventh-rounder Ozzie Smith would have been a nice addition, but he didn’t sign until the next year, when the Padres took him.

3. RED SOX 1976

This draft stands apart from the two ahead of it because it features a Hall of Famer, five-time batting champion Wade Boggs. He was an all-time bargain as a seventh-rounder, but the Red Sox also found two quality left-handers in first-rounder Bruce Hurst and John Tudor, who was their third-round pick in the secondary phase of the January draft.

4. INDIANS 1989

This is one of the most interesting drafts in history because, even though it turned out as one of the best ever, it led to the firing of the scouting director (Chet Montgomery) who oversaw it. First-round pick Calvin Murray was considered unsignable, but the Indians took him anyway—and didn’t sign him. That was bad, but Cleveland more than made up for it with ten big-leaguers after that, including Jim Thome in the thirteenth round and Brian Giles in the seventeenth. The Indians’ scouting staff was also notable because it included at least two future scouting directors (Roy Clark, Donnie Mitchell) and a future GM in John Hart.

5. CUBS 1984

The Cubs found eight future big-leaguers, but the overwhelming bulk of the value in this group comes from two pitchers who, amazingly enough, are still pitching in the big leagues now. Right-hander Greg Maddux (second round) and left-hander Jamie Moyer (sixth) don’t fit the prototype for draftable high-school pitchers, but they’ve combined for 585 major-league wins.

6. RED SOX 1968

A great draft year tends to help multiple teams, and this is one of three 1968 classes to make our top twenty. Boston found four All-Stars in the June regular phase (a feat matched only by the 1990 White Sox): Lynn McGlothen (third round), Cecil Cooper (sixth), Ben Oglivie (eleventh) and Bill Lee (twenty-second). And John Curtis, a first-rounder in the June secondary phase, pitched fifteen years in the big leagues.

7. RED SOX 1983

The third of four Red Sox classes in the top twenty, this one is built mostly on the success of Roger Clemens, who was the nineteenth overall pick in the June regular phase. But Ellis Burks, a first-rounder in the January regular phase who played eighteen major-league seasons, pushes it into the top ten.

8. PADRES 1981

First-round pick Kevin McReynolds and June secondary pick John Kruk had nice major-league careers, but the big score was a player who was better known for his basketball skills at San Diego State. Tony Gwynn turned his focus to baseball when the Padres made him a third-round pick in June, and he was in the big leagues after little more than a year in the minors.

9. YANKEES 1990

The career of first-rounder Carl Everett didn’t take off until the Marlins grabbed him in the 1992 expansion draft, but the signing of two draft-and-follows the next May—Andy Pettitte and Jorge Posada—provide foundation pieces for the Yankees’ success of the late 1990s.

10. TWINS 1989

One of three 1989 draft hauls in the top twenty, the Twins drafted two AL Rookies of the Year in Chuck Knoblauch (first round) and Marty Cordova (tenth) as well as two 20-game winners in Denny Neagle (third) and Scott Erickson (fourth). And 52nd-rounder Denny Hocking—drafted as a catcher— became one of the lowest-drafted players to reach the majors.

Adapted from “Head of the Classes” by Tracy Ringolsby, BaseballAmerica.com, 25 June 2008.

Notes

1 Matt White, interview with John Manuel, May 2010.

2 Quoted in “Draft 2007: First Round Review Prep Class, Lefthanders Rule the Day,” by John Manuel, Baseball America, 7 June 2007.

3 David Waldstein, “N.B.A. Could Be Model for New Baseball Draft,” New York Times, 18 August 2009, B10.