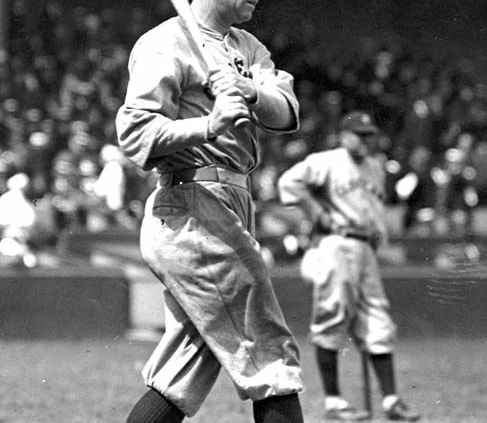

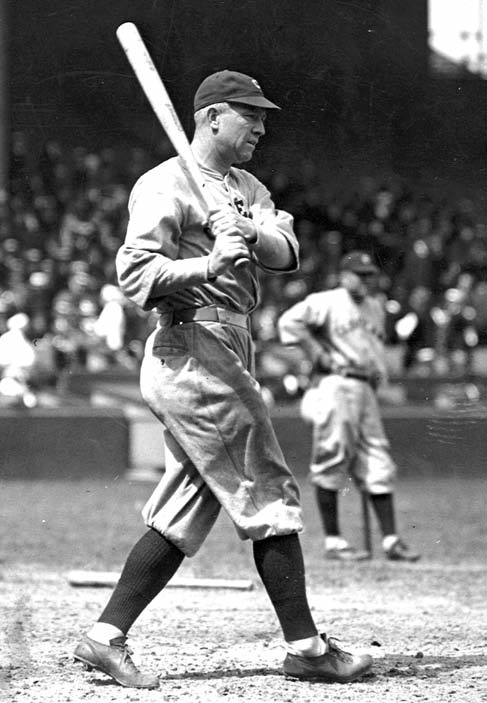

Manager Speaker

This article was written by Steve Steinberg

This article was published in Summer 2010 Baseball Research Journal

Tris Speaker is remembered more for his performance on the playing field than for his results as a manager. But in 1920–21 his personnel moves, tactics, and leadership generated outstanding results for the Cleveland Indians. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Tris Speaker, considered one of the greatest hitters and center fielders of all time, is rarely considered a great manager, though his rallying the Cleveland Indians to the 1920 world championship after the death of Ray Chapman is readily acknowledged. His remarkable achievement of managing the Indians in 1921—keeping them in the pennant race against all odds (until a ninth-inning rally against the Yankees on September 26 fell just short)—has been overlooked. The elements of that success were the same as those of 1920. How those teams were assembled and how Speaker ran them reveal a special managerial and leadership skill set.

Speaker, who took over as manager of the Indians on July 19, 1919, guided them to a remarkable 40–21 mark for the rest of that season. He had a superb eye for talent and a special ability to draw out the best in his men. Grantland Rice called him “an alert, hustling, magnetic leader, who can get 100 per cent out of his material.”1 That he could do. Equally important, he secured that “material” by seeing potential where others did not. In a Cleveland Plain Dealer article headlined “Spoke Converts Discards into Valuable Assets,” Henry P. Edwards noted that Speaker should be known as the “Miracle Man.”2

Speaker acquired pitchers who had failed and been rejected elsewhere, men in whom he “saw something.” First there was Ray Caldwell. Traded away by the Yankees after the 1918 season, the alcoholic pitcher was waived by the struggling Red Sox the following August and appeared to be finished. Speaker signed him later that month, shortly after taking over as Indians manager. As Franklin Lewis related in his history of the Indians, Speaker used reverse psychology in Caldwell’s contract: “After each game he pitches, Ray Caldwell must get drunk. He is not to report to the clubhouse the next day. The second day he is to report to Manager Speaker and run around the ball park as many times as Manager Speaker stipulates. The third day he is to pitch batting practice, and the fourth day he is to pitch in a championship game.”3

Caldwell went 5–1 with a 1.71 earned run average for the Tribe in 1919. One of those wins was a no-hitter against his old team, the Yankees. Another was a game in which he was struck by lightning in the ninth inning; he recovered and finished the game.4 In 1920 he continued his spectacular comeback when he fashioned a 20–10 record. Under Speaker’s tutelage, Caldwell was able to keep his drinking under control.

A year after picking up Caldwell, Speaker acquired minor league pitcher Duster Mails from Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League. After pitching for the Brooklyn Robins in 1915 and 1916, Mails had spent three seasons in the minors. “I didn’t deliberately try to dust them off,” he explained. “I couldn’t make the ball go where I wanted it to go.”5 (He had an 0–2 record with 14 walks and 16 strikeouts in 22 1/3 innings with Brooklyn.)

Speaker had been following Mails’s progress in the Coast League, where he won 37 games in 1919–20.

“I have been trying to get Mails for a year past. … I have had Mails in mind for some time and he came to us when he did only after long bargaining and planning.”6 Mails joined the Indians for the late-season stretch, and he won seven games—including two shutouts—against no losses with a 1.85 earned run average. In the 1920 World Series he pitched 15 2/3 scoreless innings and won one game.

Speaker picked up pitcher Allan Sothoron in the middle of the 1921 season, after he had been released by the Browns and the Red Sox, where he gave up 25 earned runs in 33 2/3 innings. Speaker had noticed a flaw in Sothoron’s delivery and thought he was tipping his pitches. Sothoron regained his effectiveness and proved to be a critical addition for Cleveland in 1921.7 He had a 12–4 record with a 3.24 earned run average.

Speaker also was able to work youngsters into the lineup in the midst of fierce pennant races, where they performed very well from the start. After the death of shortstop Ray Chapman in August 1920, 21-year-old Joe Sewell was purchased from New Orleans. A recent team captain at the University of Alabama, Sewell took batting practice each morning against lefty Mails. Speaker wanted the left-handed-hitting rookie to build up his confidence.8 Sewell hit .329 in those final weeks of the season and, in his first full season, 1921, .318 with 36 doubles.

When Indians’ second baseman Bill Wambsganss was injured in spring training in 1921, Speaker signed Riggs Stephenson—who had been Sewell’s double-play partner in college—directly from the University of Alabama. He responded with a .330 batting average that year.

The Indians brought up another youngster in 1921, Joe Sewell’s brother Luke. He appeared in only three games that first season—the first, however, of a twenty-year career in the major leagues.

Speaker reclaimed the careers of position players as well, not only pitchers. Detroit sportswriter H. G. Salsinger recognized Speaker’s personnel skills. “He [Speaker] has proved himself one of the greatest base ball leaders of all time. . . . [and is noted for his] dextrous [sic] handling of players.”9

Note: The following discussion notes the offensive improvements in a number of Speaker’s players in 1920 and 1921. While this was the start of the so-called Lively Ball Era, the improvement in his players is still significant. While playing under Speaker, many of his men had tremendous turnarounds that could not be explained entirely by the introduction of the lively ball.10

A key transaction that paved the way for the Indians’ success was their trade, on March 1, 1919, of the difficult and temperamental Braggo Roth to the Philadelphia Athletics for Larry Gardner, Charlie Jamieson, and Elmer Myers. While Speaker was not the Tribe’s manager quite yet, he pushed for the deal.11 Franklin Lewis goes further and describes Speaker’s presence in the trade talks.12

In his history of the Indians, Lewis describes Speaker’s role with the Indians before he took over as the team’s manager, replacing Lee Fohl. ”The Fohl– Speaker combination was formed almost immediately upon the arrival of the Texan in Cleveland. Spoke was the natural field leader, and Fohl recognized his strength and adaptability promptly.”13

Third baseman Larry Gardner had been a teammate of Tris Speaker on the Red Sox for several seasons, and a fixture in the Boston infield for a decade, before coming to the Athletics early in 1918. After joining the Indians in the spring of 1919, Gardner revitalized his career and, in his mid-thirties, averaged over .300 the next four seasons, 1919 to 1922.

Outfielder Charlie Jamieson had done little with the Nationals (1915–17) or the Athletics (1917–18). Over those four seasons he hit an aggregate .235 and never had an on-base percentage above .341. At the last minute, Speaker asked Connie Mack to include him in the Gardner trade, and Mack agreed.14 Speaker replaced the aging Jack Graney with Jamieson during the 1920 season, and Charlie went on to have several sensational years at the plate with Cleveland, including two in which he hit above .340 and had an on-base percentage above .400.

In his eighteen-year career in the majors, Jamieson hit .303 with 1,990 hits and an on-base percentage of .378. He later called Speaker “my best friend. He was the one who helped me get traded to Cleveland.”15

First baseman Tioga George Burns was another key Speaker acquisition. Hughie Jennings and the Detroit Tigers had given up on him after he hit .226 in 1917. Speaker bought him from Connie Mack’s Athletics on May 29, 1920.16 Historian Norman Macht noted that Mack was willing to give him up because Philadelphia fans were riding Burns mercilessly after he dropped some fly balls.17 Speaker instilled confidence in Burns, who responded with seven straight seasons of batting above .300, starting in 1921, including four seasons above .325. In 1926 he won the award as the most valuable player in the American League, hitting .358 with 64 doubles.

Steve O’Neill was a fine defensive catcher but, before Speaker took over the helm of the Indians, a weak hitter. O’Neill had hit above .253 only once, and his on-base percentage had never reached .350, when he hit .289 in 1919. He hit between .311 and .322 the next three seasons, when his on-base percentage was above .400. Speaker gave O’Neill three specific tips to help him at bat.18

- Go to the plate thinking you’ll get a hit.

- Outthink the pitcher.

- Don’t swing at bad balls.

Speaker converted third baseman Joe Evans to an outfielder. He had never played in the outfield until 1920. A .214 hitter before 1920, he hit .342 the next two seasons.

On February 24, 1917, Smoky Joe Wood joined his former Red Sox roommate and pal, who was now with the Indians. “Undoubtedly,” Franklin Lewis wrote, “Wood came to the Indians on Tris’s recommendation.”19 Charles Alexander notes that the $15,000 James Dunn paid Boston to acquire Wood was far above his “market value” at the time.20 With his arm “gone” and his career as a pitcher over, Wood made a terrific comeback as an everyday player. Actually, he had been a decent hitter as a pitcher. In the four years 1910 through 1913, he hit .273 (92 hits in 337 at bats), including four home runs, four triples, and 24 doubles.

First baseman Wheeler “Doc” Johnston never hit above .280 before 1919. He hit under .250 from 1909 to 1918 and then almost .300 from 1919 to 1921. The Burns and Johnston deals cost the Indians less than $10,000.21 The Indians reacquired outfielder Elmer Smith on June 13, 1917. (They had traded him away the previous August.) In 1920 and 1921 Smith had career years, hitting .303 with 28 home runs.

Tris Speaker was also far ahead of his time in how he used his players. He was an early advocate of platooning long before the word even existed in the baseball lexicon.22 The concept of playing left-handed hitters to face right-handed pitchers and vice versa had awkward names at the time, including “double-batting shift,” “interchangeable players,” “switch-around players,” and “reversible outfield.”23 Speaker himself called it his “triple shift” because he employed the tactic at three positions: first base and two outfielders.24

Bill James has written that Speaker instituted the “first extensive platooning” in 1920.25 James also noted that there was little discussion about the practice at the time. Yet one person did comment on it—with harsh criticism. In 1921, John B. Sheridan, the respected columnist of The Sporting News, wrote:

“The specialist in baseball is no good and won’t go very far. . . . The whole effect of the system will be to make the players affected half men. . . . It is farewell, a long farewell to all that player’s chance of greatness. . . . It destroys young ball players by destroying their most precious quality— confidence in their ability to hit any pitcher, left or right, alive, dead, or waiting to be born.”26

Three years later he was still passionate on the subject, that such substituting was “spoon-feeding baseball players. Giving them setups. Making things soft for them. Coddling them. Softening them morally. . . . Hell’s Bells, the only way to make a young man worth a cent is to put him out there when things are hard for them.”27

What little other commentary there was about Speaker’s system was somewhat supportive. In December 1920, in an article about Elmer Smith, Baseball Magazine noted that Speaker’s system of alternating players was based on “the theory sound in principle that left-handers don’t hit left-handers. Whatever may be said for the theory, Speaker has certainly obtained results which seem to justify his good judgment.”28

Where did Speaker get the idea of platooning? Why did he use it? He was playing for the Red Sox when George Stallings, the manager of the Miracle 1914 Boston Braves, platooned his outfield. Baseball Magazine noted that Speaker’s “unusual wealth of outfield material” let him alternate his outfielders “after the approved George Stallings plan, sending in right-handed batters against port-side pitchers and vice-versa.”29

In 1915, Bill Carrigan, the manager of Speaker’s Red Sox used the shift at both catcher, with Hick Cady (BR) and Pinch Thomas (BL), and at first base, with Del Gainer (BR) and Dick Hoblitzel (BL). Ed Bang, sports editor of the Cleveland News for more than fifty years, wrote that Speaker learned the concept from Carrigan.30 Charles Alexander, author of a biography of Tris Speaker, suggests that Speaker instituted the practice first and foremost to accommodate his friend Joe Wood.31

Here is a look at the dramatic results Speaker achieved at the three positions in 1920 and 1921. (The statistics listed are games played, batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging average.)32

|

Position |

Right-handed hitter |

Left-handed hitter |

|

First base |

Burns (purchased 5/29/20) |

Johnston |

|

1920 |

44g / .268 / .339 / .375 |

147g / .292 / .333 / .385 |

|

1921 |

84g / .361 / .398 / .480 |

118g / .297 / .353 / .401 |

|

Position |

Right-handed hitter |

Left-handed hitter |

|

Right field |

Wood |

Smith |

|

1920 |

61g / .270 / .390 / .401 |

129g / .316 / .391 / .520 |

|

1921 |

66g / .366 / .438 / .562 |

129g / .290 / .374 / .508 |

Speaker himself performed at a very high level on the playing field, despite the burden of managing the club. He maintained his offensive prowess while still excelling in the field. He had 24 assists in 1920 and had the league’s top range for an outfielder in 1921.33

|

Position |

Left-handed hitter |

|

Center field |

Speaker (not platooned) |

|

1920 |

150g / .388 / .483 / .562 |

|

1921 |

132g / .362 / .439 / .538 |

In 1921 Speaker’s world-champion Indians almost repeated as American League champions. They finished 4 1/2 games behind the Yankees but were just one game back when they dropped their final game against New York, on September 26, by the razor-thin margin of 8–7. Cleveland reporter Stuart M. Bell saluted Speaker’s 1921 achievement: “The Indians most of the season had a wreck of a championship ball club. He piloted an almost pitcherless and for two months an almost catcherless ball club. . . . Nobody but Tris Speaker could have done it.”34

The Indians held onto first place most of the season despite numerous obstacles.

- Bill Wambsganss broke his throwing arm in preseason. He missed 47 games in 1921, after missing just one in 1920.

- Steve O’Neill was hit in the hand by pitcher Howard Ehmke and broke a finger on May 30. He did not return to the lineup until July 15. He missed 48 games in 1921, after missing just five in 1920.

- Speaker himself was injured at different times during the season, the most serious being a September 11 knee injury. He missed 22 games in 1921. In the late September showdown series against the Yankees, the hobbling Speaker managed only one hit in thirteen at-bats.

- Jim Bagby won only 14 games after winning 31 in 1920. His earned run average rose almost two runs.

- Ray Caldwell won only six games in 1921 after winning 20 in 1920.

Taking all this into account, Bang offered that “Speaker really showed more managerial ability in losing the pennant last season [1921] than he displayed when the Indians won the year before.”35 Even New York reporters recognized the team he had shaped. “The Indians are as game a ball club as has come by along the pike in all the history of the national obsession,” wrote the New York Evening Telegram late in the 1921 season.36

Speaker was able to get results because of his management style and leadership skills. First there was the reassurance he provided to his men. St. Louis Browns’ manager Fielder Jones observed this as soon as Speaker joined the Indians in 1916, long before he became the team’s manager. “His coming has given a number of other members of the team the one thing they lacked: confidence. Speaker is as necessary to the Cleveland club as a spark plug to an automobile.”37

Then there was the example Speaker set. “He is always in the forefront in every game,” wrote New York sportswriter George Daley, “working the hardest, covering the most ground, the first in attack and the last to give up.”38 Speaker did not pretend to have all the answers. “When he was on the bench,” Coveleski said, “and something came up that he didn’t know about, he asked for help.”39 Speaker also had a special knack for connecting with his men. The Washington Times noted that “he is a manager and coacher of temperament as much as instructor of physical skill and how to apply it.”40

“He was,” wrote veteran sportswriter Gordon Cobbledick, “proving himself a warm and understanding handler of the varied temperaments, dispositions and talents under his command. . . . There was never any doubt among the players that instructions from him were orders to be obeyed, but he didn’t place himself on a pedestal. While the ball game was in progress, he was the boss. When it was over, he was one of the gang.”41 At the close of the 1921 season, Heywood Broun wrote in Vanity Fair: “He is a leader who never gives up and never allows his team to give up in spite of the circumstances of a game. It seems to me that he is by far the finest manager in professional baseball.”42

Postscript

Tris Speaker would manage the Indians for five more seasons, before he was forced to resign in the fallout from the Cobb–Leonard–Wood affair.43 Though the Indians won more games than they lost over that span, they would not be a serious challenger for the American League pennant, with the exception of a spectacular late-season rush in 1926.44 Speaker’s seemingly uncanny evaluation of players deserted him after 1921, when his personnel moves had only mixed results.45 He also backed off on platooning after that season.46 And so his success of 1920–21 must be seen in the context of his whole managerial career, including the less impressive record he compiled toward the end of it.

STEVE STEINBERG, a frequent contributor to SABR publications, is author of “Baseball in St. Louis, 1900–1925” (Arcadia, 2004) and coauthor, with Lyle Spatz, of “1921: The Yankees, the Giants, and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York” (Nebraska, 2010).

Notes

1 Grantland Rice, New York Tribune, April 6, 1921.

2 Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 31, 1921.

3 Franklin Lewis, The Cleveland Indians (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1949), 104–5.

4 Lewis, 105.

5 Duster Mails, “The Pitcher who Clinched Cleveland’s First Pennant,” Baseball Magazine, December 1920, 353.

6 Tris Speaker, “Tris Speaker, the Star of the 1920 Baseball Season,” Baseball Magazine. December 1920, 318. Mails cost the Indians $10,000 in players and cash to Sacramento. Lewis, 113.

7 Sothoron was 20-game winner for the Browns in 1919 and finished fifth in the league with a 2.20 earned run average. In 1918 he finished third with a 1.94 mark.

8 Charles C. Alexander, Spoke: A Biography of Tris Speaker (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 2007), 162.

9 H. G. Salsinger, Detroit News, 27 August 1921.

10 From 1918 through 1921, the rise in offensive performance in the AL was significant. In 1918, bating average, on-base percentage, and slugging average were, respectively .254 / .323 / .322. In 1921, they were .292 / .356 / .408.

11 Alexander, Spoke, 137, and Timothy M. Gay, Tris Speaker: The Rough-and-Tumble Life of a Baseball Legend (Guilford, Conn: Lyons Press), 182.

12 Lewis, 98.

13 Lewis, 90.

14 Lewis, 98.

15 Charlie Jamieson file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, N,Y, quoted by Alexander in Spoke, 137.

16 Alexander, 155.

17 E-mail from Norman L. Macht to the author, 29 May 2008.

18 Adam Ulrey, “Steve O’Neill,” in Deadball Stars of the American League, ed. David Jones (Dulles, Va.: Potomac Books), 683.

19 Lewis, 91.

20 Alexander, 115.

21 Lewis, 107.

22 Paul Dickson does not have a baseball use of “platoon” until many years later. Paul Dickson, The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, 3d ed. (New York: Norton, 2009), 649–650.

23 Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball: The Game on the Field (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006), 324 –27. Morris also cites a number of nineteenth-century examples of platooning.

24 New York World, April 3, 1921. (The one outfielder Speaker did not platoon was himself.)

25 Bill James, The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Villard Books, 1986), 112 –23. John McGraw began platooning Casey Stengel (BL) and Bill Cunningham (BR) in 1922.

26 John B. Sheridan, The Sporting News, May 5, 1921.

27 John B. Sheridan, The Sporting News, August 7, 1924, quoted by Morris, A Game of Inches: The Game on the Field, 327.

28 John J. Ward, “The Man who Made Record Homer,” Baseball Magazine, December 1920, 335.

29 S. Crosby, “Charlie Jamieson of the World Champions,” Baseball Magazine, June 1921, 294.

30 Ed Bang, Collyer’s Eye, February 3, 1923.

31 E-mail from Charles C. Alexander to the author, September 30, 2006.

32 After Wood hit .366 in only 194 at-bats in 1921, Speaker let him play regularly in 1922, his final season. He hit a solid .297 in 505 at-bats. Speaker had traded Elmer Smith, Wood’s platoon “partner,” away after the 1921 season. Speaker sent Smith and Burns (and the rights to Joe Harris) to the Red Sox for Stuffy McInnis. He did reacquire Burns two years later, in a blockbuster seven-player deal. (O’Neill and Wambsganss went to the Red Sox.). Burns then had four terrific years with the Indians (1924–27), including his MVP season of 1926, when he led the league in hits and doubles.

33 Gary Gillette and Pete Palmer, The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia, 5th ed. (New York: Sterling, 2008), 932.

34 Stuart M. Bell, Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 4, 1921.

35 Ed Bang, Collyer’s Eye, November 26, 1921.

36 New York Evening Telegram, September 9, 1921.

37 Quoted in Gay, Tris Speaker, 160.

38 George Daley, New York World, April 3, 1921. Daley wrote many of his columns, including this one, under the pseudonym “Monitor.”

39 Eugene C. Murdock, Baseball Players and Their Times: Oral Histories of the Game, 1920–1940 (Westport, Conn.: Meckler, 1991), 17.

40 Washington Times, September 5, 1921.

41 Gordon Cobbledick, “Tris Speaker: The Grey Eagle,” in The Baseball Chronicles: An Oral History of Baseball Through the Decades, ed. Mike Blake (Cincinnati: Betterway Books, 1994), 84.

42 Heywood Broun, “Sweetness and Light in Baseball,” Vanity Fair, October 1921, 64–65.

43 In late 1926, former Tigers pitcher Dutch Leonard accused Ty Cobb, Joe Wood, and Speaker of fixing a game between Detroit and Cleveland in September 1919. Commissioner Landis later exonerated the three men. But neither Cobb nor Speaker ever managed in the major leagues again.

44 After the Yankees went on a 16-game winning streak early in the 1926 season, the Indians fell to fifth place in late June, 13 games back of first. Then, after beating the Yankees four straight late in the season, the Indians climbed to within 2 1/2 games of first on September 18. They finished in second place, three games behind the Yankees.

45 For example, Speaker traded away George Burns and Elmer Smith after the 1921 season, although he reacquired the former two years later, and Burns had four more strong seasons with the Tribe. In 1925, Speaker gave up on Riggs Stephenson, who went on to star for the Chicago Cubs for many years. He sent Stan Coveleski to Washington, for two obscure players, one of whom never appeared in another major-league game, and the other won only five games in his career, while Coveleski won 34 games for the 1924–25 Senators.

46 In 1922, Joe Wood’s last season, Speaker played his friend regularly, and Wood responded with a .297 batting average in 505 at-bats. Charlie Jamieson was emerging as one of the league’s top hitters from both sides of the plate, and in 1923 he led the league with 644 at-bats and 222 hits.