Montreal Expos team ownership history

This article was written by Joe Marren

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

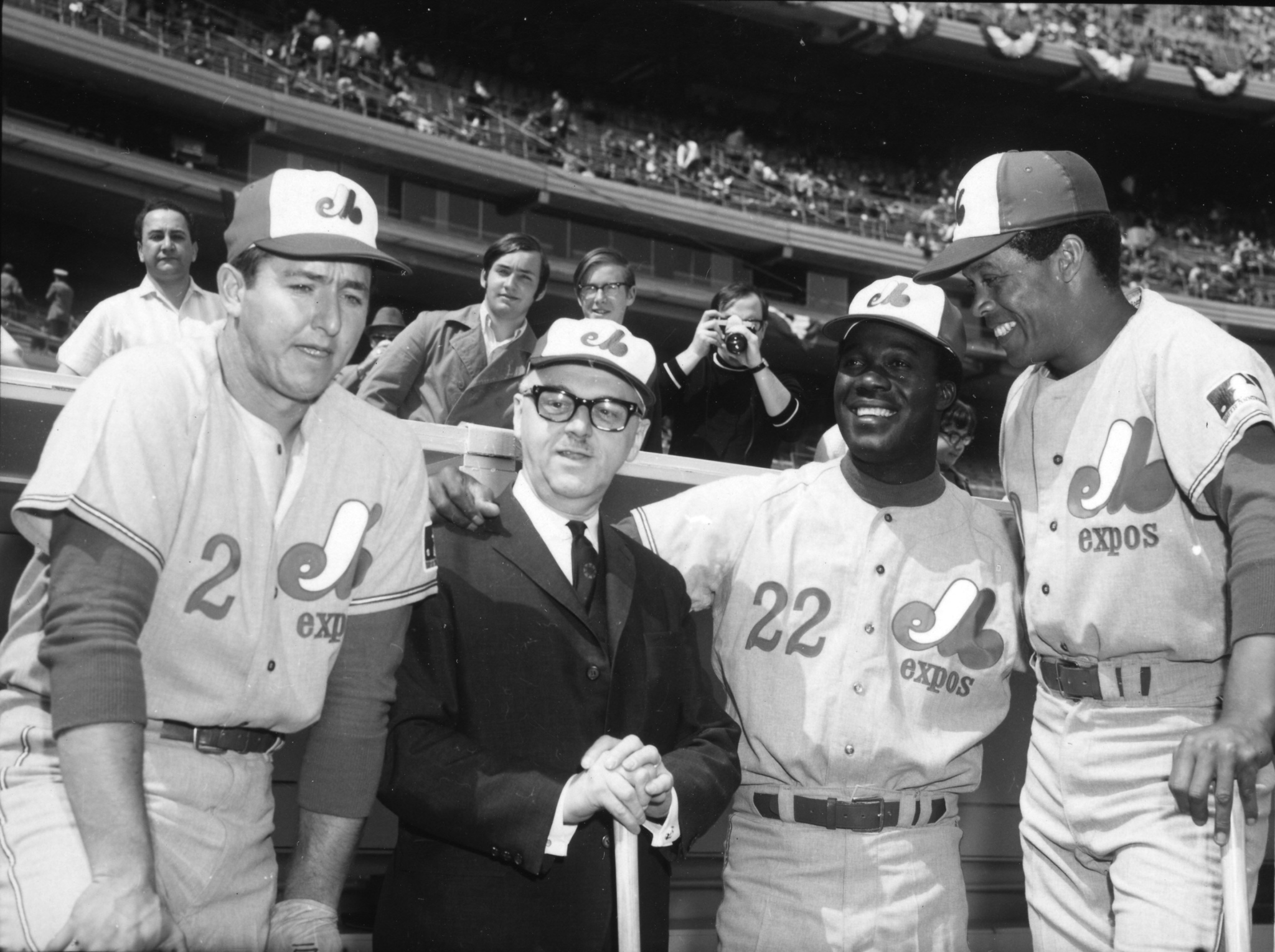

Montreal mayor Jean Drepeau with (from left) John Bateman, Jim “Mudcat” Grant, and Maury Wills on Opening Day in New York, April 8, 1969 (COURTESY OF THE McCORD MUSEUM, MONTREAL)

It somehow seemed inevitable when it all came to an end in 2004. Fate didn’t really smile on the ’Spos (Les Expos de Montreal) in 36 seasons. Shifting ownership doomed the franchise, regardless of whether the owner was Charles Bronfman (1968-91) with his family fortune, Claude Brochu (1991-99) with his executive experience, or Jeffrey Loria (1999-2002) with his flair, or even Major League Baseball itself (2002-04) with its dictate to play about one-fourth of each season’s “home” games in San Juan, Puerto Rico, for two years. And, to be honest, it didn’t help that there was heavy competition for fan attention and dollars in Montreal, which was a hockey town with a baseball problem.

Make no mistake, people played ball in Montreal in the past. The minor Eastern League’s Rochester (New York) Blackbirds moved to Montreal on July 16, 1897. Subsequently renamed the Royals, the club was to become the top farm team of the Brooklyn Dodgers until 1960.1 Players like Jackie Robinson, who broke modern baseball’s racial barrier with Montreal in 1946, Don Drysdale, Duke Snider , and Roy Campanella, among others, played in Delorimier Stadium (Stade de Lorimier).2

Even today, and possibly tomorrow, pro baseball has a home in Montreal. The Toronto Blue Jays have played preseason games in Olympic Stadium since 2013. And a December 14, 2018, story on Canadian television reported that bringing the majors back to the city was financially viable if a new stadium could be built in a central location with access to public transit.3

Despite the history and current climate, though, the area’s joie de vivre never centered on baseball. Ask anyone north of Plattsburgh, New York, and they will testify that hockey’s Montreal Canadiens franchise, one of the most successful in sports, owns the town. Need proof? Then watch about seven minutes of an outpouring of love for Rocket Richard, one of the all-time greats. It’s a homage to a gloried past for the players, the seasons, the Stanley Cups, and a great and magical building.

After watching it, ask yourself, how could Jarry Park (1969-76), Olympic Stadium (1977-2004), and Hiram Bithorn Stadium in San Juan compete? How could Bronfman, Brochu, Loria, and MLB in 36 seasons match the history of the National Hockey League’s Canadiens (founded in 1909)? The answer is obvious: They couldn’t. Which is why in the summers from 1969 to 2004 joggers and hikers on the paths of Mount Royal were probably talking about Guy Lafleur, Yvan Cournoyer, and Ken Dryden more than Bill Stoneman’s no-hitter in 1969, Rusty Staub’s (Le Grand Orange for his hair color) plate heroics, or even other Expos stars such as Gary Carter and Andre Dawson.

Business people going to and from work and shops in the Underground City (La ville souterraine) along the subway lines may have talked about Blue Monday (the October 19, 1981, Game Five loss to the Los Angeles Dodgers in the National League Championship Series), or they may have talked about the collusion charge against Bronfman, the fire sale of players by Brochu, the contraction worries under Loria, or the limbo the team and its fans suffered before the franchise’s fated move to Washington under MLB care in 2004. But it’s much more likely that those same fans cared more about — and talked more about — the 1976-77 Habs team that suffered only eight losses in an 80-game season, or the 28-game unbeaten streak in 1977-78, or any of the Stanley Cups in 1969, ’71, ’73, ’76, ’77, ’78, ’79, ’86, or ’93.

The Expos’ woes didn’t begin and end with a hockey rival for fans’ attention and disposable income. Randy Newman once sang that it’s money that matters. A Canadian team in a US organization would find out just how true that was. Money did matter. A lot. It was one of the reasons the Expos struggled so much.

How to sum up? Well, Harry Caray’s favorite song might lose something in translation, but here’s a go at it anyway:

“Take me out to the ball game,” amène-moi au match de baseball. Some people went to the ballgame, but many more hearts were with the Habs.

“Take me out with the crowd,” amène-moi dans la foule. Capacity for baseball in Olympic Stadium waxed and waned from almost 60,000 in the 1970s and ’80s to less than 44,000 after 1992. To put that in context and have fun with numbers from a fan perspective, the Expos were either third or fourth in the 12-team National League in attendance during the winning seasons from 1979 to 1983, but after the team began losing again attendance never rose above eighth. (All statistics in this essay, whether individual or team, are from baseball-reference.com.)

“Let’s root, root, root for the home team, if they don’t win it’s a shame,” allons, allons, encourageons les gars. S’ils ne gagnent pas, quel dommage! To be honest, they didn’t win all that much and didn’t have a winning record for their first decade in existence (the team’s complete record in Montreal was 2,753 wins, 2,953 losses, and 4 ties). They won only one division title and that was in the strike-shortened 1981 season (they then went on to lose in the NLCS). So add it all together and it caused fans to stay away more often than not.

Jarry Park was the Montreal Expos’ first home from 1969 to 1976. The little ballpark seated just 28,456, the smallest in the major leagues when the Expos began play. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Charles Bronfman (owner from 1968 to 1991)

The majors went international on May 27, 1968, when National League President Warren Giles announced that Charles Bronfman would bring a franchise home to his native Montreal at a cost of $10 million. (All money is in American dollars unless specified otherwise.)4 But what is ironic is that Bronfman wasn’t originally meant to be the principal owner. Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau worked hard to get a franchise for his city and at first asked Jean-Louis Levesque to head the ownership group. The original group of investors balked at paying the franchise fee and that’s when Bronfman stepped up (he would own 50 percent of the team) to head an ownership group. At the time Bronfman was the fifth-richest man in Canada5 and could handle the fiscal roller-coaster that went with owning a sports team. But just to make sure there was cash in the vault, so to speak, he also invited some rich friends along for the ride. Among the minority investors were Lorne Webster (Montreal financier), Hugh Hallward (owner of a Montreal construction company), Sidney Maislin (transportation company owner in Canada), and Montreal business leaders the Beaudry brothers, Charlemagne and Paul.6

Bronfman hired John McHale (former general manager of the Detroit Tigers and Milwaukee Braves) as the team’s first president, to run the baseball side of the business. Claude Brochu (who would eventually own the team) took over from McHale in 1986. But it was Bronfman’s money that kept the team afloat through the lean years and his enthusiasm that kept fans hoping for a championship season.

Bronfman hired John McHale (former general manager of the Detroit Tigers and Milwaukee Braves) as the team’s first president, to run the baseball side of the business. Claude Brochu (who would eventually own the team) took over from McHale in 1986. But it was Bronfman’s money that kept the team afloat through the lean years and his enthusiasm that kept fans hoping for a championship season.

Bronfman was educated at McGill University and helped run the family business, Seagram’s distillery, and its other ventures with his brother, Edgar, and later Edgar’s son, Edgar Jr. Seagram’s eventually expanded into other areas such as broadcasting (Universal) and theme parks before it all went sour in the early 1980s. Because Seagram’s business ventures were failing, its interests had to be sold off.7 In a 2013 interview with the Toronto newspaper The Globe and Mail, Bronfman called the breakup of what was once his family’s company “a disaster, it is a disaster, it will be a disaster. … It was a family tragedy.”8

“Disaster” could have been the Expos’ unofficial name. In what might have been a portent of things to come, the team almost didn’t play in Montreal because as late as August 1968 the expansion authorization was stalled and there was talk of awarding it instead to Buffalo, New York. Why? Because the team didn’t have a ballpark to play in. Finally, Montreal pols and the team settled on Jarry Park (seating capacity of 3,000 for amateur games) in the city’s north end near an expressway exit and a Metro station. Eventually, though, Bronfman would need a new park to keep MLB happy and customers satisfied. So the plan hatched by the city and baseball bigwigs was that Jarry Park would be expanded and serve as a stopgap until a permanent home was built. Jarry underwent a $3 million (Canadian) upgrade to add better lights, other facilities, and to increase capacity to almost 30,000 — technically 28,456 — in order to be set for the 1969 season. (The team was supposed to play in Jarry until 1971, but the Expos stayed in the so-called temporary ballpark through the 1976 season.)

Boston’s Fenway Park might be the definition of a neat little bandbox of a ballpark, but Parc Jarry in its minimalist, make-do way had its own quaint charm. As Montreal sportswriter Ian MacDonald put it, “Everybody had fun.”9 There was the “Fiddler on the Dugout Roof,” an organist whom even the visiting team appreciated, and the novelty of signs in French and English (e.g., le frappeur for batter and le lanceur for pitcher).

“Baseball is an intimate game. At Jarry you were pretty damn close. We went through the joy of having a team in Montreal to not so much fun the last few years. But it was great fun for the first few years,” Bronfman said. 10

As he noted, fans enjoyed the late spring and early summer days when almost everyone is optimistic before losing streaks happen and reality hits. It also helped that things started out smoothly for the Expos:

- Gene Mauch was the first manager and on April 8, 1969, the team beat the New York Mets, 11-10, in its first game at Shea Stadium.

- On April 14, 1969, the Expos played the first home game in Jarry Park — and also the first regular-season game outside the United States — and beat the St. Louis Cardinals, 8-7. The announced crowd was 29,184.

- On April 17, 1969, Bill Stoneman pitched the team’s first no-hitter, a 7-0 win against the Philadelphia Phillies.

So April wasn’t the cruelest month, but it was a counterpoint to the first decade. The Expos’ first winning season came in 1979 (95-64) when the team wound up one game back of the eventual World Series champion Pittsburgh Pirates. What helped was that the Expos’ farm system was finally producing quality players.

There was realistic hope that ’79 could be a prelude to better things. Then, in 1981, a players strike divided the season into halves. The Expos won the division in the second half and went on to beat the Philadelphia Phillies, three games to two, to advance to the NL Championship Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers. Montreal and the Dodgers split the first two games in LA, and games three and four in Montreal.

Apologies to Grantland Rice, but the deciding fifth game, postponed to Monday, October 19, because of rain on Sunday, wasn’t outlined against a blue-gray October sky. And, as far as Expos fans were concerned, one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse rode again to kill their dreams. Rick Monday was his alias and although the Dodgers weren’t a cyclone that swept the Expos into the St. Lawrence River, they did enough so that 36,491 fans in Stade Olympique endured one of the low points in team history. With the score tied, 1-1, going into the ninth inning, Expos manager Jim Fanning put in right-handed pitcher Steve Rogers (12-8, 3.41 ERA during the season but 2-0 with a 0.51 ERA in the playoffs). Rogers retired the first two batters before left-handed outfielder Monday (who would bat .333 in the NLCS) came to the plate. His solo homer to center off a sinking fastball gave the Dodgers the lead and they would win, 2-1. The day was dubbed “Blue Monday” by the media and disappointed Expos fans.

It was perhaps an indication of things to come that the rescheduled Monday game hadn’t been close to a sellout, although the Friday (54,372) and Saturday (54,499) games had drawn close to the stadium’s 58,838 listed capacity.

The soul-stealing defeat led to a gradual disenchantment that spread to include Bronfman: Some of the best players were traded away (due to money issues), or they signed better contracts elsewhere. It’s an accepted fact that the front office makes the deals, but it’s the owner who tells them how much money can be spent.

Future Hall of Famers Gary Carter and Tim Raines, and All-Stars like Andre Dawson left the team. Even a splashy free-agent signing like that of Pete Rose didn’t last the season. In some cases, the Expos received decent players in return, but not always.

Bitter feelings toward owners and senior management after losing players over money issues was not just a Bronfman thing. Claude Brochu would also field the same issues and feel resentment from the fans and media. As a team history put it: “Several of their best players, including Larry Walker (who was earning $4 million American by 1994), entered free agency or were traded after the bitterness of the 1994 season. (The Expos were in first place with a 74-40 record before a players strike in mid-August ended the season and the postseason.) While still a formidable squad, the Expos’ future pennant hunts were frustrated by the … owners, who were reluctant to provide them with the necessary resources for taking on additional salaries.”11

And all of the Expos owners had stadium problems as well. For Bronfman, though, it was tied to politics. In 1976 he threatened to move his home and his business interests out of Quebec if the separatist Parti Quebecois won a majority of seats in the provincial election. The PQ won in a landslide and the Expos briefly broke off lease negotiations for Stade Olympique, which had been the main venue of the 1976 Olympics. Even after negotiations resumed, they dragged on for so long through the offseason that the team started to sell tickets for the 1977 season at Parc Jarry. But an agreement was eventually reached and the Expos opened the ’77 season on April 15. (Unfortunately for the 57,592 fans in attendance, it was a 7-2 loss to the Phillies.)

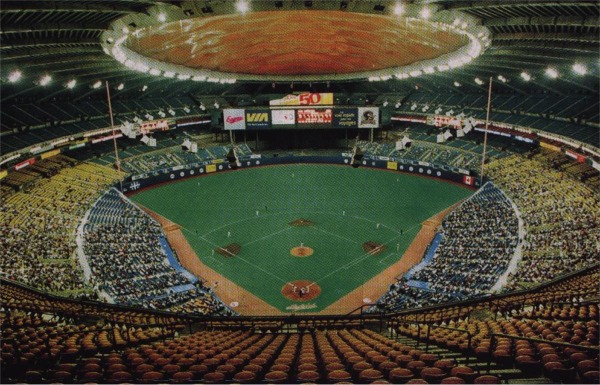

Olympic Stadium was plagued by structural and financial difficulties from the moment the Montreal Expos began play there in 1977. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

“The Big O,” one of the nicknames for the much more formal le Stade du Parc Olympique de Montreal, wasn’t built to be a baseball park. Olympic Stadium wasn’t exactly a gulag, but Olympic Stadium wasn’t loved either. It also was mostly out of the way as one urban design critic noted:

Fans who lived in the western suburbs lost interest in schlepping all the way to the stadium. People from other parts of the city didn’t want to cross bridges or tunnels. The large business community downtown was geographically closer, but — with no fun restaurants, bars, or ancillary activities of any kind nearby — the Big O wasn’t appealing to them either.12

Inconveniences went beyond location. Things seemed to break a lot. The retractable roof (which wasn’t installed until 1987) was cranky and apparently didn’t know what “retractable” meant in French or English. Eventually the team recognized the inevitable and just kept it closed. Players complained about the artificial turf and other conditions. Add it all up and the excitement of a rising team with promising stars from 1979-83 helped the Expos draw more than 2 million fans each year (except for the strike year of 1981). But after that, as players left and the closed roof kept ballgames indoors, attendance fell. And it was expensive to keep Olympic Stadium in good condition; eventually the nickname “The Big O” morphed into “The Big Owe.” (One reason why was that in June 1991 the roof — again! — was damaged in a windstorm and the powers-that-be decided to keep it closed for the ’92 season. The roof was removed in May 1998 for a while until later that year when a $26 million nonretractable roof was installed. But eight months later, that roof collapsed. The designer and installer sued each other. That suit was settled in 2010 in favor of the construction company that installed it. Along a parallel line, in the 1990s when the organization was trying to get support for a new ballpark, the seemingly constant structural tribulations led to trash talk that reached such a pitch that the fans received the message and stopped showing up.13)

By 1978, near the end of his team’s second season in Olympic Stadium, Bronfman had already soured on the place: “There’s no sun, there’s so much concrete, the building overpowers the game, if there’s a big crowd the stadium seems empty. Baseball is a summer leisure activity. This is not a summer leisure stadium.”14

Maybe so. But part of Bronfman’s displeasure was in knowing that at small Jarry Park, fans would have to buy tickets in advance to see the visiting stars. Olympic Stadium, which could fit twice as many fans, changed people’s buying habits. Or, as Bronfman put it: “You know you can always get a seat in Olympic Stadium. You didn’t know that at Jarry.” And people who don’t buy tickets in advance are “subject to all the reasons for not going.”15

Years later, after he no longer owned the team and the Expos had moved to Washington, Bronfman sounded like a person wistful for what he had and lost, “In Olympic Stadium the fun [when compared to Jarry Park] dissipated pretty damn fast.”16

The Expos’ finances also were limited by American League expansion into Toronto. When the Expos were Canada’s only major-league baseball team, their games could be broadcast far and wide. But once the Blue Jays arrived in 1977, the broadcast rights were not so clear. Indeed, by the time the Jays were successful, the team asked MLB to restrict the Expos’ broadcast to Quebec and points east while the Jays would have exclusive rights to Toronto and parts of southern Ontario. Author Jonah Keri said MLB allowed the Expos to broadcast 15 games into Toronto territory and could buy airtime for others.17

By the mid-1980s Bronfman had sold or was selling off his Seagram’s business, which he called a personal disaster. At the same, time he was also growing disillusioned with being a big-league owner and all its cascading problems. (For instance, he felt that escalating player salaries would strike at the heart of MLB’s long-term viability.18) It also didn’t help that Montreal’s economy was suffering and the purchasing power of the fan base was slowly shrinking:

[There] were decades of underperformance in which the city never fulfilled its promise. The head office operations of the Bank of Montreal and the Royal Bank gradually shifted to Toronto to take advantage of that city’s impressive growth as a financial centre. Political tensions over language and the issue of Quebec sovereignty hurt private investment and drove some of the wealthiest and best educated people out of the province. Sun Life left in a huff in 1978 after the Parti Québécois took power for the first time.

The Canadian Stock Exchange closed its doors in 1974, while the Montreal Exchange lost increasing trading volume to its Toronto rival before switching its vocation to financial derivatives. The fancy new airport built in Mirabel didn’t take off as promised, with Toronto becoming the hub for Canadian air travel. At the same time, the city’s aging industrial base felt the first effects of globalization as imports from Asia began to hurt the textile and clothing industry.

But as the new millennium began, more negative trends had crept in: offshoring, outsourcing, contracting out. Companies had found new ways to cut costs by sending work to places like China, India, and Mexico at a fraction of local wage rates. More industrial plants began to shut their doors.19

Bronfman wanted out of the restless baseball world. He couldn’t get a new ballpark, costs were escalating, and he felt the economics were flirting with disaster. The Expos’ total revenue was less than what the New York Yankees earned just from broadcast rights.20 But the trouble was that he and club President Claude Brochu couldn’t find a buyer who would keep the club in Montreal. (Offers had come in from investors in Miami and Arizona; and there was an uneasy story that Bronfman would sell the team to potential buyers in Buffalo for $130 million.21) So Brochu went to work scrounging up the $100 million (Canadian) to help buy the Expos from Bronfman. He put up $2 million of his own money to become the managing general partner and persuaded the City of Montreal ($18 million) and Province of Quebec ($15 million) to kick in about one-third of the remaining amount; and then added 11 Canadian business backers (e.g., among others, Bell Canada, the publisher McClelland Stewart, Coca-Cola, Canadian Pacific, and Loblaw Companies, a food retailer).22 It was even reported that Bronfman loaned him some money so that Brochu could buy the team and keep it in Montreal.23

Brochu said he put his heart and soul into the team for a 7.5 percent stake in the operation. The trouble was that many of those other 11 partners had the money but not the patience or the soul. He said their message was “We’re giving you $5 million each, don’t come back for more.”24

But to end the Bronfman era on a bright note: He was inducted as an inaugural member of the Expos’ Hall of Fame on August 14, 1993, as the franchise’s Founder/Fondateur.

Claude Brochu (1991-99)

Like Bronfman, Brochu was a Canadian and native of Quebec (born in Quebec City in 1944). He worked for Seagram’s from 1978 to 1985, including a stint as executive VP from 1982 to 1985. Brochu was also the second president of the Expos, taking over from John McHale in 1986.

Although 1991 was not a successful season when measured by wins and losses (71-90, last in the NL East), or by attendance (under 1 million), the team was going through a Dickensian season with the best and worst of luck. The good times started on July 28 at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles when right-handed pitcher Dennis Martinez threw the major leagues’ 13th perfect game, a 2-0 win over the Dodgers.

Although 1991 was not a successful season when measured by wins and losses (71-90, last in the NL East), or by attendance (under 1 million), the team was going through a Dickensian season with the best and worst of luck. The good times started on July 28 at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles when right-handed pitcher Dennis Martinez threw the major leagues’ 13th perfect game, a 2-0 win over the Dodgers.

But on September 8 the worst of times happened when a concrete pillar tumbled into an exterior walkway in The Big O. No one was injured, but the Expos had to play the final 26 games of the season on the road. Brochu said the ’92 season was at risk unless the ballpark was certified safe, which didn’t happen until early November when engineers inspected it and declared it structurally sound.

If the physical building was falling apart, at least the team was building its roster with the 1990 acquisition of outfielder Moises Alou. Alou, along with right fielder Larry Walker and center fielder Marquis Grissom, helped the Expos climb to strong second-place finishes in 1992 and 1993. Then came 1994. On August 11 the Expos had the best record in the majors (74-40, .649). Then the players voted to walk out. The Expos’ likely advance to the postseason walked with it.

After a US federal court ruling the next March, owners and the Players Association returned to the bargaining table and the 1995 season began with only a few games lost. What the Expos lost was the profits and excitement of a postseason run. It also did nothing to solve their underlying financial problems.

The Expos received almost all their income in Canadian dollars, but player salaries and travel expenses were paid in US dollars. Currency fluctuations can cut deep and make planning difficult. In a 2015 critique of “Brochunomics,” Financial Post writer Peter Kuttenbrouwer noted how that works against Canadian teams in international leagues:

When Claude Brochu took over the Expos in 1986, the Canadian dollar was worth about U.S. 69 cents. The dollar rose to U.S. 90 cents by 1991, helping the team. But in the 1990s the loonie [the Canadian dollar coin] took a precipitous slide, fuelled by budget deficits, low interest rates and weak commodity prices. By the time Mr. Brochu was out of the Expos, the dollar was worth U.S. 63 cents.

“It was always a little bit difficult,” recalls Mr. Brochu, 70. “If you are up to your neck from a salary perspective, you are in trouble.”25

Although the Expos got some US dollars from American broadcast rights and MLB, it wasn’t enough to overcome the fiscal woes of the Canadian dollar. Despite the success of 1994, the situation was untenable, Brochu wrote. He said the ’94 team payroll was $18.8 million. Montreal made $1 million (Canadian) in profits in 1992 and ’93 (which translated then to roughly $600,000 in US currency). In 1994 it was projected that the team would lose $6 million because of the strike and the consequential loss of television revenue.26 (Teams also had to keep paying operating expenses — salaries for scouts and employees as well as minor-league players.)27

“Our exposure to currency fluctuations was U.S. $4 million or U.S. $5 million,” Brochu said.

“You don’t need a degree in economics to understand that paying players in U.S. dollars, while a team’s revenues are in Canadian dollars, can be nothing but ruinously expensive,” Roger Landry, former publisher of the Montreal newspaper La Presse, wrote in an introduction to Mr. Brochu’s 2003 memoir, My Turn at Bat. 28

Despite its impact on the future of his team, Brochu was a firm supporter of the owners’ plan for revenue-sharing and a salary cap, the issues that had precipitated the 1994 strike. As it was, Brochu would write in 2003, the team had the second-lowest payroll in 1994. (Pittsburgh had the lowest at $13.5 million.) With the raises expected after a strong season, Brochu said, the team would have lost $25 million in 1995:

Revenue sharing and the cap are inseparable; that’s what we decided. … We need to reduce the spread between team payrolls. The overriding issue is an element of cost control. The cap is a question of survival.29

It turned out that revenue-sharing and a salary cap were not inseparable. The federal court ruling sent owners and the union back to the bargaining table but it took nearly two years to reach a deal. That new collective-bargaining agreement brought limited revenue-sharing, but there was no salary cap. The Expos’ problems were ameliorated, but not solved.

In addition, as 1994 shuddered to an end, Brochu wasn’t happy with the contract for the Big Owe. The Province of Quebec owned the ballpark and the team got nothing in parking or skybox revenue. Brochu called it “the second worst deal in baseball,” adding, “We try to get a better deal, but [provincial officials are] not giving us a break.”30

As an immediate consequence of the strike, Brochu and the other Expos owners were facing a bleak bottom line. General manager Kevin Malone was forced to bid adieu to four star players –native Canadian Larry Walker, Ken Hill, John Wetteland, and Marquis Grissom — between April 5 and 8, 1995. The trades were made just before the deadline for salary arbitration, which meant Montreal got virtually nothing in return because there was little bargaining room. The player moves meant Montreal’s player payroll at the start of 1995 would be $15 million, which would be $3.6 million less than the stingy ’94 season when the Expos had the second-lowest payroll in the game.31 In following seasons, as players like Alou, Mel Rojas, and Pedro Martinez approached free agency, they were also lost.

As president, it fell to Brochu to defend the player moves at the time:

“The reaction from our fans is broken down into two categories. There are those who have to balance their checkbooks and who understand what we’re doing. Then there are those I call roll-the-dicers, people who prefer we just re-sign all those players and gamble on a one-shot deal. Even if we took a chance, unless there were 50,000 at every game, and all the [TV and sponsorship] contracts were signed, we’d run out of cash in June. That’s not even a credible alternative.”32

Brochu would later contend that if his partners had been more interested in fielding a championship team than making money in the short term, the “fire sale” of players would not have had to happen, according to author Jonah Keri. But the partners didn’t — or wouldn’t, or couldn’t — come up with the cash.

As Keri noted in a 2014 book, “Expos fans couldn’t help but wonder … if Brochu convinced the team’s cheapskate owners to spend a few damn dollars, or taken a leap of faith that short-term financial pain would lead to long-term success[,]”33 then things might have worked out quite differently.

Malone also tried to reassure the fan base when he noted that the farm system would supply good (and cheaper) players: “Our graduation rates are the best in the business.”34

Regardless of Brochu’s intentions or the viability of the farm system, the actions were immediate and dramatic. The Expos fell to 66-78 in 1995, last in the NL East. Attendance also fell. In ’95 the Expos drew 1.3 million fans, down from the 1.6 million of the previous two complete seasons (1992 and ’93).

But sometimes miracles do happen, and the Expos slowly improved in 1996 when the team climbed to second place in the division with an 88-74 record and was in the running for a wild-card playoff spot until almost the end of the season. It was the same hard luck and little cash Expos story after the season, though, when Alou and Rojas left. The press criticized management, equating the team to a Triple-A club with players coming and then leaving just as they started to develop their skills.

Attendance never averaged more than 20,000 per game again, evidence that fans shared the reporters’ frustration. In fact, the Expos were last in attendance (16th out of 16 NL teams) for the remaining years in Montreal. Only once did attendance top the 1 million mark (1,025,639 to be precise) and that was in the 2003 season. Baseball should abhor asterisks, yet there should probably be one next to the ’03 attendance figures for two reasons:

First, the team was competitive with stars like 27-year-old right fielder Vladimir Guerrero, and it would again finish at 83-79 (but this time in fourth place in the NL East).

Second, because MLB owned the team at the time and thought it could make $7 million to $10 million by playing 22 of its 81 “home” games in Hiram Bithorn Stadium in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The reasoning went that attracting new fans would doubtless boost attendance if a team was in contention.35 In 2003 the Expos played more than 100 road games and traveled 40,951 miles.36

Second, because MLB owned the team at the time and thought it could make $7 million to $10 million by playing 22 of its 81 “home” games in Hiram Bithorn Stadium in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The reasoning went that attracting new fans would doubtless boost attendance if a team was in contention.35 In 2003 the Expos played more than 100 road games and traveled 40,951 miles.36

In the 22 games in San Juan, the Expos went 13-9 before 301,082 fans (an average of 13,685 per game). The Expos total attendance that season was 1,025,639, which means the Expos’ average attendance when playing in Montreal was 12,280. So, given the expenses involved, the “homestand” in San Juan wasn’t the money-maker it could have been.

Attendance issues would bedevil owners Brochu, Jeffrey Loria and MLB. By 1998 attendance was down to an average 11,295, which convinced Brochu that the fix to the Expos’ problems was a new ballpark serviced by public transit.

A proposed 35,000-seat, retro-style downtown ballpark (think Baltimore’s Camden Yards) was proposed in 1997 at a projected cost of $250 million (Canadian). The land would be donated by the federal government and the ballpark would be paid for through selling the naming rights to Labatt Brewing Company (it would have been called Labatt Park), selling personal seat licenses, and with $150 million (Canadian) from the Province of Quebec. The hoped-for opening date would be in spring 2001.37

But the plan ran into obstacles from the start. Brochu’s partners weren’t interested in spending more money on the franchise and Quebec Premier Lucien Bouchard said the government wouldn’t spend money to build a new stadium while they were forced to close hospitals.38 In fact, the government was still paying off the debt on the Big Owe and so, when combined with frequent repairs, the total cost of Olympic Stadium was approaching $1 billion.39 Although the Montreal Gazette would opine that a new stadium was logical, it simply wasn’t going to happen given the finances. And that doomed Brochu in the short term and major-league baseball in Montreal in the long term. Despite all the hundred visions and revisions and the subsequent decisions and alterations that Brochu and his partners made, the project was doomed. In the end Brochu blamed Bouchard for the failures at getting money to build a new stadium and, as it turned out, the team’s subsequent move.40

All the acrimony and doubts among the ownership group that went on behind closed doors spilled out into the open and, tired of it all just as Bronfman had been, Brochu looked for a way out. He also wasn’t necessarily looking for buyers in Montreal. According to various press reports, he was negotiating with potential buyers in Portland, Oregon, Las Vegas, Charlotte, and Northern Virginia. Negotiations with telecommunications exec William L. Collins III from Northern Virginia seemed the most promising.41 But the commissioner’s office wasn’t ready to abandon Quebec without first trying to adjust the sport’s economics.

“I felt the team should have been moved and I told the commissioner that,” a 2004 Washington Post article quoted Brochu as saying. “I always heard, ‘Well, he’s [Bud Selig] thinking it over, he’ll review it, he’ll know in two more months or six more months.’ There was really no decision.”42

In the end Brochu sold his 24 percent share to American art dealer Jeffrey Loria on December 9, 1999, for $12 million, making the New York City resident the new managing general partner.43 Loria persuaded additional partners from Montreal to come in with him as minority investors, including Charles Bronfman’s son, Stephen,44 as well as Mark Routtenberg of Guess Jeans and Jean Coutu, who owned a chain of drugstores.45 (Eventually Loria’s share of the franchise would grow to 94 percent as the costs of running the team went higher and the other owners decided not to contribute.)46

Olympic Stadium was home of the Montreal Expos from 1977 to 2004. It was built to host the 1976 Summer Games and for many years has also played host to the Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Jeffery Loria (1999-2002)

Loria, who was 58 when he got the franchise, hired David Samson, the son of his ex-wife, as the team’s executive vice president (later president). Loria would be the absentee owner in New York and Samson (then 31) would run the team. Samson was a former private wealth manager at Morgan Stanley with no baseball experience.47

Loria and Samson faced most of the problems that their predecessors did, but also one they didn’t: contraction, which was a cloud over the team at the end of Loria’s tenure.

Let’s set contraction aside for the moment and concentrate on what helped Loria get approval from MLB to buy the Expos. The irony is a few paragraphs away yet, but what sold MLB on Loria was his ownership experience. In 1989 he and New York Yankees great Bobby Murcer bought the Oklahoma City 89ers, then the Triple-A farm team of the Texas Rangers. The team won the American Association championship in 1992. Loria sold his interests in the team in 1993. By 1994 he was looking to own a major-league franchise and so he bid on the Baltimore Orioles but lost out to Peter Angelos. When the opportunity to buy into the Expos’ ownership circle came up in ’99, the other major-league owners OK’d the deal.

Loria inherited two big problems (before he made some of his own): What to do about the stadium, and how to deal with the payroll?

First, the stadium. And a bit of good news. Loria had the clubhouse renovated with art deco lighting and new carpets and had three large screen TVs installed.48 Now the bad news: Despite the investment in new paint, rugs, and TVs, Loria warned Montreal that the Expos couldn’t survive if the team had to play in Olympic Stadium much longer. So a Montreal design firm fiddled with Brochu’s idea. Their redesign called for a new ballpark made more of metal than brick, shedding some of the fancier design elements, and generally reconfiguring things to reduce costs from $250 million (Canadian) to $200 million.49 Although Loria said the team would kick in $38.8 million,50 he also wanted the city to increase its funding. When the politicians heard that, the interest of the various municipal, provincial, and federal governments ended.51

Now the payroll. At first, Loria said the checkbook was open to sign new players and bring respectability back to the club. In the 1999 season the Expos had the lowest payroll in the National League at $17.9 million. By 2000, Montreal’s payroll was $32.9 million, third lowest in the NL.

What Loria initially did with player moves was even more appreciated: “I want to strengthen this team in as many areas as I can. … As the new owner here, I feel I have an obligation to move things forward. No more business as usual,” Loria told the New York Times’ Murray Chass, “I’m not afraid to acquire or trade players as long as it improves the club. … What I’m about is quality players and quality people, whether it’s in the art world or the baseball world.”52

Things started to sour in 2001. Although Loria was paying more in player salaries, the rebuild wasn’t going fast enough (in 2000 the Expos won 67 games, in ’01 they won 68 games) and Loria wasn’t patient enough to build through his farm system. Free-agent signings and trades weren’t working out.

Elite players not only were wary of the Expos’ reputation for frustration, Olympic Stadium also had a bad reputation. Players didn’t like the turf. Fans were upset that no money was forthcoming to build a new ballpark and became even more upset when Loria let the lease expire on the downtown land for the proposed Labatt Park.53

Samson said the Expos could not compete without help, and he pointed to the recent contract shortstop Alex Rodriguez (10 years, $252 million) signed with the Texas Rangers. Samson said such contracts were ridiculous and called on the commissioner to do something to help poor clubs compete with the rich clubs.

“Baseball is in dire jeopardy of failing as an industry. The recent signings are horrendous for the future of the game,” Samson said.54

As if that wasn’t enough, there was the botched renegotiation of the Expos’ broadcasting rights. To try to get more cash, Loria wanted to renegotiate the broadcasting contract for the 2000 season. Toronto already had a sizable share of the Ontario market and Loria tried to increase the Expos’ niche with English-speaking broadcast outlets in Quebec and parts of Ontario. He didn’t get to first base. The Sporting Network offered him a fraction of what it paid the Blue Jays. From a purely business standpoint it made sense because the Blue Jays were the better deal: They were an American League team in a bigger market and had won back-to-back World Series titles in 1992-93. More than that, in 1999 the franchise had 2.1 million fans see home games in the SkyDome; Montreal that same season drew 773,277 fans.

Loria wanted the Canadian stations to pay something akin to what the US clubs got in broadcast fees. In response, Quebec broadcasters said the club should try to rebuild its fan base since ratings didn’t justify the price.55

So, without a money-making deal, Loria pulled the team off TV entirely and also off English-speaking radio.56 Games were still broadcast on French-speaking Telemedia Radio Inc., which would carry 158 games of the 162-game season.57 Meanwhile, English-speaking fans had to search for audio on the internet.

The situation slightly improved in 2001when the Expos signed a one-year deal with the French-language television station Reseau des Sports (RDS), which would broadcast 45 games and its Toronto affiliate would carry 12 games in English (nine of them original and not simulcast on RDS). Montreal’s La Presse newspaper said the contract was for about $3 million (Canadian), which was still far less than the $9 million Loria wanted.58

That improvement was balanced by the loss sponsorship from Labatt. The brewery announced in January that it was ending its 15-year business relationship with the team and would no longer be a sponsor. Labatt’s had contributed about $2 million per year to the beleaguered team’s coffers.

“It being impossible to obtain assurances from the Expos with regard to certain major clauses, such as construction of a new downtown stadium as well as the conventional television contracts, the current contract is obviously no longer pertinent,” said a statement from Labatt’s Quebec President Louis Morin.59

The broadcast situation never righted itself. In 2002 once again there was no English-language TV and only a handful of games broadcast on French-language TV, for which the team got $536,000.60

The word “contraction” began to be used more and more at the end of the ’01 season. On November 6, major-league owners voted in favor of contraction, which meant the Expos and Minnesota Twins would play their last seasons. Since the Expos had finished last in the NL East in ’01 (with a record of 68-94), and since they had been last in attendance for several seasons, and since their broadcast income was abysmal, it seemed natural that Montreal would be one of the two teams disbanded.

The Twins were the other likely cut even though things were looking up for the team. Attendance at the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome had jumped 68 percent between 2000 and 2001. The Twins weren’t that bad on the field either, finishing with an 85-77 record.

But the difference was that Twins fans and Minnesota Gov. Jesse Ventura threatened to fight contraction and keep the team in the Metrodome based on a lease that would not expire until after the 2002 season. The players union also sued to help its members who might be in danger of losing their jobs with two fewer teams to play for.

Ventura saved the Expos and the Twins when the State of Minnesota sued baseball and the courts ruled for the Twins, so contraction was put on indefinite hold. Contraction was taken off the table when MLB and the Players Association signed a new contract agreement in 2002.

Loria, though, began looking for a way out of Montreal. Enter Commissioner Bud Selig, who helped arrange a byzantine three-way deal. In late December of 2001, Florida Marlins owner John Henry was the leader of a group of investors that bought the Boston Red Sox for $700 million. Since Henry couldn’t own two MLB teams, Selig helped arrange a deal in which Loria sold the Expos to a group representing MLB for $120 million and MLB would also lend Loria (interest-free) $38.5 million. That deal was finalized on February 15, 2002. Then Henry sold the Marlins to Loria for $158.5 million.61 Loria took the entire Expos front office, computers, scouting reports, injury reports, kitchen sinks, and a Grinch-bag full of assorted stuff with him to Miami.62

For the fans, the sale just proved what they had come to believe about Loria: that he had always intended to desert Montreal. As an article in the Globe and Mail in June 2000 put it: “Now that he’s been vilified by Montreal’s media and scorned by its fans, the question facing those who want to see baseball stay in the city is how New York art dealer Jeffrey Loria can possibly make the Montreal Expos work in a poisonous environment.”63

The answer was obvious: Neither he nor Samson could make it work and they continually denied reports that they were trying to move the team to the United States. In the summer of 2000 Montreal’s La Presse newspaper said some partners felt the team would move within a few years based on the economics of the situation.64 Fans were so irate that Loria felt the need for security guards to be with him during games in the Big O.65

If fighting mad was the mood du jour, then 14 minority investors metaphorically punched back against Loria, Samson, Selig, and Bob DuPuy, MLB’s chief operating officer. They filed a lawsuit in federal court in Miami in mid-July of 2002. They claimed that they once owned 76 percent of the team but saw their investment cut to 6 percent. The suit sought $100 million in damages and an injunction prohibiting MLB from moving the Expos or disbanding the team through contraction. It contended that Loria, Selig, and others “conspired to eliminate baseball in Montreal as well as reduce their holdings in the team.”66 Since they said there was a conspiracy involved, their lawyers felt it was a violation of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act of 1970 (in other words, a RICO lawsuit).

Jeffrey Kessler, a New York City lawyer hired by the 14 Canadian companies, said that Loria, through a series of cash calls on the partners, misrepresented his intentions to them. Kessler also charged that Loria and Samson had always planned on moving the team to the United States and that Selig and DuPuy were involved in the plan.67 Part of the 45-page document said the proof was that Loria let the land deal for the proposed Labatt Stadium fall through, that he demanded higher broadcast fees (meaning the team was without TV and English-language broadcasts in 2000), and that he initiated the cash calls to reduce the holdings of the minority partners.

A cash call happens when a partnership that is short of capital calls on partners for additional money. From February 9 to August 27, 2001, Loria, as managing partner, made a series of cash calls. The partners refused to contribute so Loria used his own money, meaning his percentage of the money invested in the team increased.68 The lawsuit alleged that those cash calls were part of Loria’s secret plan “for the purpose of diluting the ownership interests” and that Selig helped by concealing things and also helped Loria get another MLB team.69 After one cash call on March 17, 2000, the partners said they instead offered Loria his $12 million back if he would step down. Loria refused and instead put up his own money to meet the call.70

Loria responded that the calls were necessary given baseball economics: “Since I became involved in 1999, I personally invested approximately $30 million in the partnership and took on greater responsibility for future operating losses, while the limited partners, who had multiple opportunities to contribute, chose to stay on the sidelines and contribute nothing to build a better ball club in Montreal,” he said.71

Kessler disagreed: “All [the 14 partners] knew was that this was a destroyed team [run] by a general manager who they thought was totally out of control.”72

The 14 partners said they were unwilling associates in Loria’s subsequent deal to buy the Marlins and didn’t want to be part of the February 2002 purchase of the Florida Marlins. Among the 14 were Esarbee Investments Ltd. (run by Stephen Bronfman, Charles’s son), Fairmont Hotel and Resorts Inc., BCE Inc. (which was Canada’s largest telephone company), Loblaws Inc. (a grocery chain), and a labor investments firm.73

An arbitration panel ruled against the partners in November 2004 and they decided not to go forward with the suit.

MLB (2002-04)

Baseball’s first act was to appoint people to run the team. Working as Baseball Expos LP, the league named Tony Tavares, a former Anaheim Angels executive, as president and put him in charge of business operations. Omar Minaya, New York Mets assistant general manager, was selected as vice president and general manager in charge of operating the team. Frank Robinson got the job as the team’s manager.

Baseball’s first act was to appoint people to run the team. Working as Baseball Expos LP, the league named Tony Tavares, a former Anaheim Angels executive, as president and put him in charge of business operations. Omar Minaya, New York Mets assistant general manager, was selected as vice president and general manager in charge of operating the team. Frank Robinson got the job as the team’s manager.

All of them had 72 hours before the team reported to spring training and were starting completely from scratch since just about everyone in the front office and in the bushes had skedaddled with Loria. There were only four baseball people left to work with Tavares, Minaya and Robinson: trainer Ron McClain, Triple-A manager Tim Leiper (Ottawa of the International League), Triple-A pitching coach Randy St. Claire (also Ottawa) and assistant farm director Adam Wogan.74

In spite of it all (including the now almost-constant threat of an impending move), the Expos actually flirted with success in ’02. They were in first place from April 20 to May 2 and finished the season second in the NL East at 83-79.

Because the Expos were owned by their competitors, there was no help coming during the wild-card run in ’02. Yet because of that run, the prospects for 2003 were a little brighter. That’s the year that the team drew more than a million fans (although 22 games were designated as home games played in Puerto Rico). The team again finished with an 83-79 record but, unlike ’02, the Expos came in fourth in the NL East. Selig announced that the Expos would not call up any players from the minors after the traditional September 1 roster expansions due to the costs involved.75 The team, which still had a shot at a wild-card berth, went 12-12 in September.

By 2004 it was a foregone conclusion that the Expos would soon be gone. The only question was where as suitors and promoters from Washington, Norfolk, Virginia, Portland, Oregon, Las Vegas, Monterrey, Mexico, and San Juan, Puerto Rico, made their case. Given the problems with Jarry Park and Olympic Stadium (as well as the proposed Labatt Park), the one thing MLB insisted on was that a major-league ballpark, or funding for one, be firmly in place.

San Juan had the advantage of already hosting the Expos for 22 games in 2003 and was on deck to host 21 in 2004. But there were doubts about Hiram Bithorn Stadium, which had a maximum capacity of 22,000. Nevertheless, promoter Antonio Munoz said the ballpark could be expanded in time for the 2005 season.

“The primary goal in doing this [playing some of the Expos home game in San Juan] is to bring a major-league team to Puerto Rico in the future. We can show that Puerto Rico is an adequate site, and that we can compete with any city in the United States,” Munoz said.76

Yet John McHale Jr., MLB’s executive vice president for administration, was cautious even given the incumbency of the San Juan experiment: “Across baseball there is still some unfamiliarity with the demographics of the San Juan market.”77

The Expos would go 7-14 in Puerto Rico, drawing 217,005 fans (an average of 10,333). So if it was an audition for San Juan, it didn’t go well, especially since Munoz guaranteed MLB $10 million.78 In light of that, Selig announced on September 29, just a few hours before their final home game (a 9-1 loss to the Marlins before 31,395 of the faithful), that the Expos would move to Washington for the 2005 season and temporarily play in RFK Stadium until a new ballpark was built. The only serious opposition came from Baltimore Orioles owner Peter Angelos, who didn’t want competition just 35 miles from Camden Yards. His was the sole no vote (28 to 1) on December 3 to formally approve the move of the franchise to Washington.

Washington had been without a club since 1971 when the second Senators franchise moved to Arlington, Texas, and became the Rangers. The franchise shift was the first in the National League since the Braves left Milwaukee for Atlanta in 1965.79

Selig was celebratory in the announcement as it meant that soon the owners could look for someone to buy the team and usher in more stability (or so it was hoped). As he said of the Washington bidders (who would not necessarily be the owners): “They were very aggressive. They were very tenacious. This was a very impressive bid. It shows their commitment, their dedication. I would say that from a Washington standpoint, this was their finest hour.”80

That’s the corporate viewpoint, McHale put it in another perspective: “I would not presume to try and buffer this for the Montreal fans. I can’t believe that this is going to be anything but a day of great sadness and wistfulness for them. I was there with my father when this franchise was started. This has been a tremendously bittersweet process for me personally. I can only imagine what the fans are going through, watching their club and knowing inevitably that this day would come. Now it’s here.”81

Postscript

MLB announced the new owners in July 2006. Lerner Enterprises group, led by billionaire real-estate developer Theodore N. Lerner, beat out three other bidders. Lerner’s group paid $450 million. It all became official on July 24, 2006. In late September 2006, Comcast announced that it would broadcast Washington Nationals games.

One of Lerner’s first moves was to hire Stan Kasten as team president. Many credit Kasten as being the brains behind the Atlanta Braves’ successful 14 division titles. Unlike Montreal’s approach, Kasten’s long-range plan included lots of money to build up the farm system and use the draft to stock the teams.

So, then, after all the hullabaloo, whose fault is it that the Expos left? The fans? The owners? The city itself? It depends on who is asked.

Montreal has a metro population of about 4 million people, according to a 2013-14 TV marketing guide.82 Yet, attendance rarely matched expectations. Mitch Melnick, who was once the sports director of the Expos’ English-language station, agrees: “The fan base was destroyed as the product was destroyed. I guess this is Major League Baseball’s way of wishing the problems would go away: Blame the customer.”83

The fans would argue otherwise. Who else to blame? MLB? The owners thought so.

When salaries and costs went up and revenues went down in Montreal, Brochu’s front office had a fire sale of players and that soured fans, or so the thinking went: “Montreal, basically, after the strike in ’94, abandoned baseball,” said Robert A. DuPuy, baseball’s president and chief operating officer. “They turned their back on baseball.”84

If MLB shrugged its shoulders and pointed fingers elsewhere, who else was to blame? The owners? Brochu blamed fellow owners and a lack of revenue support from all of them, especially considering the lopsided exchange rate of converting dollars to loonies: “There’s an air of contempt that small markets are mismanaged, that we’re not marketing as we should, and we should move,” Brochu said. “We have to be allowed to compete, and to do it for more than a snapshot of time.”85

Regardless, the only thing that can be said with certainty is the era is over.

Summed up Michael Farber in Sports Illustrated: “In the full seasons from 1979 through ’83 the Expos averaged 2.24 million fans annually in a stadium so frigid in April and late September that not even 5 for 5 qualified as hot. Fans sang Valderi, Valdera, an oompah band played in the beer garden at the entrance, and each time an opposing pitcher threw to first base, a chicken was flashed on the scoreboard. There was no happier place in baseball, including Wrigley Field. The loss of capital when Charles Bronfman sold the team in ’90, the fire-sale departures of stars like Larry Walker, Moises Alou, and Pedro Martinez in the mid-’90s, the badmouthing of Olympic Stadium by former Expos general partner Claude Brochu in his futile effort to secure a downtown ballpark, and the dissipation of goodwill by Loria after he bought the team in ’99 all figured in the demise.”86

C’est fini.

JOE MARREN is a professor in the Communication Department at SUNY Buffalo State. He can be reached at marrenjj@buffalostate.edu

Sources

Charles Bronfman photo: Courtesy of the McCord Museum, Montreal.

Felipe Alou photo: Courtesy of the Trading Card Database.

Frank Robinson photo: Courtesy of The Topps Company.

Notes

1 The Dodgers’ move to Los Angeles for the 1958 season made travel between LA and Montreal tenuous at best. So in 1961 the Dodgers named the Omaha Dodgers of the Triple-A American Association as the top farm team.

2 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd edition (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America Inc., 1997); Lance Rinker, “Lost in Translation: Montreal Expos” at blitzweekly.com/lost-in-translation-montreal-expos, July 15, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

3 According to a December 13, 2018, World Atlas (worldatlas.com/articles/largest-cities-in-north-america.html) article, Montreal is the 19th-largest city in North America, with a population of just over 4 million. (Toronto is the largest Canadian city at 6.1 million.) Mexico City is the largest North American city, with a population of 20 million.

4 Other new franchises that would begin play in 1969 were the Seattle Pilots (today’s Milwaukee Brewers) and Kansas City Royals in the American League, and San Diego Padres in the National League.

5 Farid Rushdi, “How Jeffrey Loria Destroyed the Montreal Expos/Washington Nationals.” bleacherreport.com/articles/275561-how-jeffrey-loria-destroyed-the-montreal-expos/washington-nationals/, October 20, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

6 “Charles Bronfman” at baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Charles_Bronfman. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

7 Despite the fiscal stress, Bronfman was still able to buy the defunct Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League in 1982 and reconstitute what was left of that franchise into the Montreal Concordes. That team eventually folded and Montreal was without a CFL franchise from 1987 to 1996; Bronfman owned the team from 1982 to 1987.

8 Joanna Slater, “Charles Bronfman opens up about Seagram’s demise: ‘It is a disaster,’” The Globe and Mail, April 5, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

9 Rory Costello, “Jarry Park (Montreal).” sabr.org/bioproj/park/be7dd3d0. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

10 Ibid.

11 William Humber, “Montreal Expos.” thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/montreal-exposs. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

12 Mark Byrnes, “The Baseball Stadium Montreal Never Built,” Citylab, April 9, 2015. Quoting Jonah Keri’s book Up, Up, And Away. citylab.com. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

13 exposnation.com/en/real-reason-why-expos-fans-stopped-showing-up/. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

14 Costello.

15 Costello.

16 Costello.

17 Richard Sandomir, “A First-Place Team Looking for Handout,” New York Times, August 15, 1994; Jonah Keri, Up, Up, and Away (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2014).

18 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Charles_Bronfman.

19 Peter Hadekel, “Stagnation City: Exploring Montreal’s economic decline,” Montreal Gazette. montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/montreals-economic-stagnation, February 2, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

20 Rushdi.

21 United Press International, upi.com/archives/1991/06/14/expos-sale-to-brochu-official/228967682000. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

22 Ibid.

23 “Claude Brochu,” baseball-reference.com/bullpen/claude_brochu. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

24 Sandomir.

25 Peter Kuttenbrouwer, “Claude Brochu Explains the Trouble with the Loonie and Canada’s Pro Sports Teams,” Financial Post, February 13, 2015.

26 Sandomir.

27 Brian Borawski, “National Attention: The Expos’ 35-Year Journey to Washington D.C. (Part 1),” tht.fangraphs.com/national-attention-the-expos-35-year-journey-to-washington-dc-part-1/, December 10, 2004. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

28 Kuttenbrouwer.

29 Sandomir.

30 Ibid.

31 Michael Farber, Michael, “Stars Are Out as Four Expos Learned, There’s No Room for Top-Dollar Players in the Montreal Budget,” Sports Illustrated, April 17, 1995.

32 Ibid.

33 Keri; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Brochu. Both retrieved October 31, 2018.

34 Keri.

35 Michael Farber, “The Team Without a Country Will Play in Canada and Puerto Rico. And Pray for Help,” Sports Illustrated. si.com/vault/2003/03/31/340618/5-montreal-expos-the-team-without-a-country-will-play-in-canada-and-puerto-rico-and-pray-for-help, March 31, 2003. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

36 Steve Fainaru, “Expos for Sale: Team Becomes Pawn of Selig,” Washington Post, June 28, 2004.

37 Byrnes.

38 Humber.

39 sportsecyclopedia.com/nl/,tlexpos/expos.html. Retrieved Oct. 31, 2018.

40 Byrnes.

41 Michael Farber, “Last Swing in Montreal: The Majors’ Orphan Team, the Expos, Is Playing Out the String in Canada Under a Puppet Regime and Facing an Uncertain Future,” Sports Illustrated, March 18, 2003; Alan Snel, “Expos Can’t Cash In on the Upswing,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale), September 13, 1998. sun-sentinel.com/fl-xpm-1998-09-13-9809150201-story.html. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

42 Fainaru.

43 Loria had originally tried to buy the team from Bronfman in 1991.

44 “Claude Brochu.”

45 “Loria Acquires 92 Per Cent of Expos Shares,” CBC Sports, May 23, 2001. cbc.ca/sports/baseball/loria-acquires-92-per-cent-of-expos-shares-1.283747. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

46 Borawski; Rinker.

47 Fainaru.

48 Shawna Richer, “Expos Without TV Deal,” Globe and Mail., April 3, 2000. theglobeandmail.com/sports/expos-without-tv-deal/article18421973. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

49 Byrnes.

50 Fainaru.

51 Rushdi.

52 Murray Chass, “New Montreal Owner Is Swinging With His Checkbook,” New York Times, December 26, 1999.

53 sportsecyclopedia.com/nl/mtlexpos/expos.html. Retrieved October 31, 2018; CBC Sports, cbs.ca/sports/baseball/expos-lose-labatt-sponsorship-1.262020, January 5, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

54 Bill Beacon, “Expos Back on Television,” CBC Sports. cbc.ca/sports/baseball/expos-back-on-television-1.254456, January 9, 2001. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

55 Associated Press, “Still No TV, English-Language Radio for Expos,” expn.com/mlb/news/2000/0403/461919.html, April 3, 2000. Retrieved May 25, 2019. According to an April 3, 2000, story by Richer in Toronto’s Globe and Mail newspaper, there were only about 5,000 season ticket holders at the start of the 2000 season.

56 CBC Sports, January 5, 2001; Richer.

57 Associated Press, April 3, 2000.

58 Beacon.

59 “Expos Lose Labatt Sponsorship,” CBC Sports, January 5, 2001. cbc.ca/sports/baseball/expos-lose-labatt-sponsorship-1.262020. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

60 Farber (March 18, 2002).

61 Griffin, Richard (Nov. 15, 2011). “Miami Marlins set to be a huge bonanza for Loria” https://www.thestar.com/sports/baseball/2011/11/15/griffin_miami_marlins_set_to_be_a_huge_Bonanza_for_Loria Retrieved Oct. 31, 2018. And Rinker. And Reid, Jason (March 22, 2002). “Still Hooked,” Los Angeles Times.

62 Farber,” Last Swing in Montreal.”

63 Jeff Blair, “Sale to Loria reported close,” Globe and Mail, June 24, 2000.

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid.

66 Murray Chass, “Baseball; 14 Companies Alleging Anti-Expos Conspiracy,” New York Times, July 16, 2002.

67 Ibid.

68 Ibid.

69 Ibid.

70 Fainaru; theclubdom/com/opeds/ownerreviews/expos_review.html. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

71 Sarah Talalay, “Lawsuit Cites Plot to Wreck Expos,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel, July 17, 2002. sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-2002-07-0207170093-story.html#. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

72 Fainaru.

73 Talalay.

74 Farber, “Last Swing in Montreal.”

75 Rushdi.

76 “Expos’ Deal to Play in San Juan Finalized,” espn.com/espn/wire/_/section/mlb/id/1688599, December 17, 2003. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

77 Ibid.

78 Ibid.

79 Barry M. Bloom, “MLB Selects D.C. for Expos,” September 29, 2004. https://mlb.mlb.com/content/printer_friendly/mlb/y2004/m09/d29/c875100.jsp. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

80 Ibid.

81 Ibid.

82 Rinker.

83 Fainaru.

84 Ibid.

85 Sandomir.

86 Farber, “Last Swing in Montreal.”