Wagner for Sheriff: Honus Runs into the Coolidge Tax Cut

This article was written by Mark Souder

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

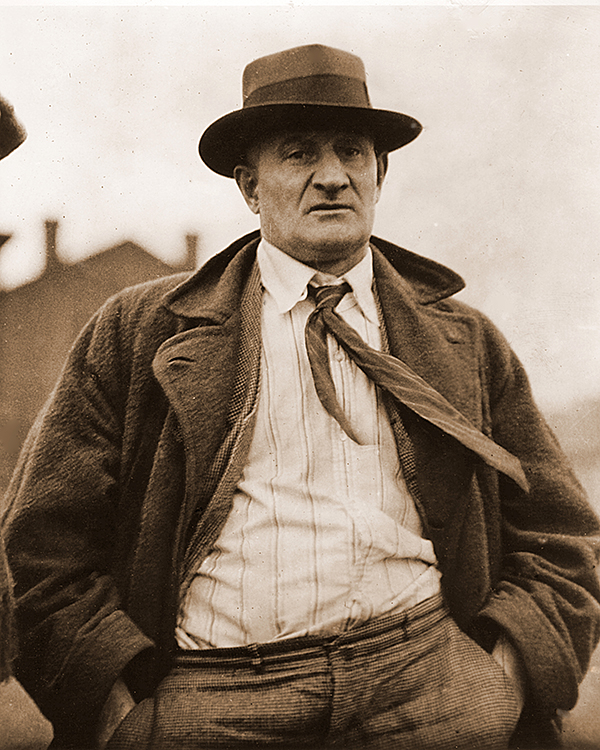

Pittsburgh Pirate Honus Wagner is the greatest shortstop of all time. Baseball guru Bill James ranks Wagner as the second greatest baseball player in history, behind only Babe Ruth. He was a longtime hero in Pittsburgh. So how did the beloved Pirate get routed in the 1925 race for sheriff of Allegheny County? He ran into presidential politics in Pennsylvania.

But that is not how most baseball historians have recorded his history. Wagner biographer Arthur Hittner writes the consensus view: “Despite the support of several newspapers, Wagner’s half-hearted campaign fell short of the mark.”1 The Associated Press wrote in 1925 that “in sport parlance it might almost be said that Mr. Wagner hit weakly to the infield.”2 Others loved analogies to striking out. The prevailing view, however, is very wrong.

The complexity of the interaction of politics and Honus Wagner sheds much insight into how politics actually works.

Republicans had long been touting Wagner for office. In 1917 the New York Sun headlined, “Honus Wagner for Sheriff: Famous Pirate Is Logical Candidate of Pittsburg Republicans.” Leaders of the machine-led Republican Party were touting Wagner for sheriff of Allegheny County, which includes Pittsburgh.3 The boss-picked county coroner called him the “ideal man”: “The old Pirate standby is popular and would win in a walk. I feel sure that I am voicing the opinion of the great majority of Republican voters in Allegheny County when I say that he is the logical man for the job.”4

Wagner may have been able to hit almost any kind of pitched ball with a baseball bat, but when he finally did run for sheriff eight years later, he was completely shut down by the political dealmaking necessary to pass the Calvin Coolidge/Andrew Mellon tax cut. It remains the most celebrated tax cut in American politics, touted by Ronald Reagan in promoting his own administration’s cuts and compared in a Washington Post headline to the 2017 tax-cut bill.5 No former baseball player was going to stand in the way.

Germans were still struggling with acceptance by the WASP establishment during Wagner’s life. Honus is a variation (Hah-nus) of Johann or Johannes. He was a German who liked his strong drink. Debates over beer, Sunday baseball, and the rowdiness at games were proxy battlegrounds for the extended political controversies of the era. Pennsylvania was on the front line of the national debates. Barney Dreyfuss, who had worked in his family’s Kentucky whiskey business, cashed in his share to buy control of the Louisville team and move it to Pittsburgh. His most important decision was to bring Wagner with him from Louisville to Pittsburgh. Honus fit well with the German wet population in Pittsburgh.

Prohibition was coming when the first “run, Honus, run” political rumors began in 1917 and was in place during his actual campaign in 1925. Known to like his beer, sometimes too much, Honus was presumably not the teetotaler candidate to run the Pittsburgh sheriff’s office. A leader of the then-powerful Women’s Christian Temperance Union specifically denounced him as a candidate because his election could lead to an “open county and Sunday athletics.” She said that Wagner “may be a good ball player, but he would not be a good sheriff.”6

The issue was extra intense in Pittsburgh because “revenuers” were part of the Department of Treasury run by native Andrew Mellon, who was part of the Pittsburgh Republican establishment. He designated his nephew to chair the state GOP as well as coordinate Pittsburgh politics during the period of Wagner’s campaign.

Nor was Honus Wagner going to be mistaken for a classic western-style sheriff in the Clint Eastwood mode. Jan Finkel, in his SABR biography of Wagner, does not describe someone who sounds like the slick political candidates of today. He was “awkward-looking” and had huge hands that “made it difficult to tell whether he was wearing a glove.” “His one weakness in the field stemmed from his oversized feet, which sometimes got in the way.” “He tore around the bases with his arms whirling like a berserk freestyle swimmer.” When he lost, even a small-time newspaper in Iowa reprinted this line: “Someone says Pittsburgh refused to elect Honus Wagner sheriff because a crook could get away through Honus’ bow legs. Baseballs didn’t.” So Wagner’s looks weren’t going to carry his campaign.7

Nor was Wagner much of a public speaker. His four-minute speeches to help sell World War I Liberty Bonds were possibly the longest speeches he ever gave. He wasn’t going to wow the voters with his words.

But he did have political assets. He was the hometown sports hero who helped make Pittsburgh a worldwide name beyond just its industry. Pittsburgh was the city of smoke and grime. Honus Wagner besting Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers to win a World Series in 1909 had helped every Pittsburgher’s self-image. Wagner loved people and they loved him. That tends to be important in politics. Wagner had interests similar to the common man and he developed his business interests around those personal interests. To a political boss trying to win an election, Wagner was a magnet for the average laborer. He also had other “common man” interests:

- He loved to tinker with automobiles, which were just emerging at the time. So he started a garage where he sold cars and gas. His only problem was that he was not a good salesman and admitted to buying about half the gas he sold to use for his personal touring.

- He loved to fish so he started the Honus Wagner Sporting Goods Store. He and fellow Pirates star Pie Traynor signed autographs, chatted with folks, and got fishing and hunting gear wholesale. They lost their investment but had a good time doing so.

- He loved sports so he played on a top local basketball team in the offseason and later headed local youth sports leagues. He was always out mixing with the “folks,” as voters are often called by politicians.

- He liked to drink pretty well so he partnered in the creation of a distillery. It failed, but the discounts were nice. And most men weren’t teetotalers.8

Was running for sheriff a “last-minute” thought by Wagner? This is a common assertion in any comments that go beyond the basic “and he lost.” Wagner flirted with the idea in 1910 when he was asked, possibly in jest, by a congressman to run for sheriff. The Republican Party, at least segments of it, clearly pushed him to run by going public in 1917. That year was not an easy one for the GOP. Nationally, it was coming off two straight Woodrow Wilson presidential victories after Teddy Roosevelt’s Bull Moose Party had carved up the Republican vote in 1912. In Pennsylvania, there was still bitter infighting between progressive Republicans and regulars. Having the most popular Pittsburgher as a candidate for sheriff, the most visible candidate spot other than mayor, would have been a big asset in 1917. But Wagner didn’t file. In 1925, when he did run, he filed just before the deadline. In 1929, he filed to run for sheriff again, but then withdrew his name before he was locked on the ballot.

While this could suggest a lack of serious commitment, I tend to think it reflects not only a dogged interest in being sheriff but also someone who is making a calculation about other job options, personal financial need, and some chance of electoral success. When you’re the biggest name in town, people always whisper sweet nothings in your ear about how you should run for this or that.

The fact that Wagner accepted a political appointment to the Fish & Wildlife Commission from Pennsylvania Governor John Tener in 1914 is instructive. Tener, a former baseball player, was elected in 1910 with the support of the Republican political bosses. Much later, in 1942, Wagner briefly accepted a post as sergeant-at-arms of the Pennsylvania legislature, again a patronage post controlled by the Republican political bosses.

Many baseball writers point out that Wagner was also made a deputy sheriff, in 1940. That post obviously wasn’t very taxing, since one month after receiving the appointment, Wagner took leave and left for Florida to help coach the Pirates in spring training. Memoirs suggest that Deputy Sheriff Wagner mostly hung around the judge’s office talking with his old friend and former Pirates star Deacon Phillippe, who was a bailiff. The position did indicate his ongoing interest in police work. A photograph exists showing Wagner as an old man with a gun in each hand. It fits the profile of a person who was attracted to law enforcement his whole life, as Wagner clearly was.9

Wagner obviously liked guns, because in the biography Honus Wagner: Life of Baseball’s Flying Dutchman he is always off hunting or fishing. Probably even more importantly, and seldom noted, is that his wife’s father was a police detective.10 So Wagner was the son-in-law of a police detective; he was a potential sheriff’s candidate three times, running once; he was later a sergeant-at-arms and a deputy sheriff; and he loved guns. I don’t think his interest in running for sheriff was last minute.

Every urban area had political bosses who delivered services in return for votes. Tammany Hall of New York is by far the most famous. Among political historians, however, Pennsylvania earns a special place. In the space of 30 years, it managed to have two political bosses, Matthew Quay of Pittsburgh and William Vare of Philadelphia, refused seating by the United States Senate because of corruption.11

In the first decades of the 20th century, Pennsylvania was the most dependable large state for Republicans in a presidential contest. This resulted in immense power and influence among Republicans. Pennsylvania was controlled by three interests: Pittsburgh bosses, Philadelphia bosses, and the state business group dominated by business interests in both cities (often centered in Harrisburg, the state capital). Woodrow Wilson said that the Vare machine in Philly (three brothers, with William the head) was worth an extra 200,000 votes to Republicans in Pennsylvania. (“Extra” was a euphemism for illegal.) Over 90 percent of Italian Catholics in South Philly, the Vare political base, voted Republican. African Americans remembered which party favored emancipation and also voted over 90 percent Republican.

The Vare brothers controlled garbage, taxing powers, construction, and transportation. They also rotated as city, state, and federal legislators. Thus, all three brothers soon were very, very rich as well.

Andrew Mellon had different personal goals from Pittsburgh Republicans who were focused on local patronage and contracts. In return for his having helped get them elected, he demanded that Pennsylvania’s two United States senators, David Reed and George Pepper, back him in the Senate by supporting the tax cut that Mellon, as treasury secretary, had developed for President Coolidge. It was the number one issue for Coolidge and Mellon.12

Coolidge’s personal view was clearly stated in his Inaugural Address of 1925: “The collection of any taxes which are not absolutely required, which do not beyond reasonable doubt contribute to the public welfare, is only a species of legalized larceny.13 Coolidge was frustrated with earlier defeats of his tax bill, but 1926 would be the final showdown. To pass, Republicans had to control Pennsylvania in 1925. In return, the bosses could do their grubby work in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Senators from Pittsburgh included Mellon’s former partner and Mellon’s personal attorney, which is one way to assure loyalty. The Philadelphia bosses also gave Mellon full support.14

However, as 1925 dawned, Pittsburgh was at war. Two factions had turned on each other in a fight over division of patronage and spoils, which endangered GOP control of the entire state. On top of that, Pennsylvania governor Gifford Pinchot—famous environmentalist friend of Roosevelt’s and a pain-in-the-neck progressive reformer as far as the bosses were concerned— was still carrying the progressive torch that had split the party the previous decade and resulted in the election of the Democrat Wilson to the White House. Mellon decided that if the Coolidge plan was to get needed support from Pennsylvania, he needed to knock some heads together in Pittsburgh. So Mellon met with both factions, and they developed a “unity” ticket of political bosses. Everything seemingly was back to normal. The deal was made. Then in walked Honus Wagner with some troublemaking friends in Pittsburgh calling themselves a “non-partisan ticket” and attacking the “compromise” ticket as a front for corrupt bossism.15

It’s naive to think that a candidate runs for office all by himself, that the people carefully choose a candidate they like, and that if that candidate, especially if famous, had just worked harder, victory should have been easy. Politics are fluid and you must always adapt. One of the factions in Pittsburgh, and it appears it may have been the dominant coalition in 1917, had wanted Wagner to run for sheriff to help the entire ticket corral votes. Wagner didn’t run. In 1925 they faced a new crisis and formed a new coalition. It didn’t include Wagner.

Instead, Wagner was aligned with a man named William L. Smith, who was running for mayor of Pittsburgh. One of the newspapers friendly to Honus Wagner and company reported nearly verbatim speeches from a “non-partisan” slate event, and they practically scream “You’re in political trouble” to Wagner. The Pittsburgh Press quoted Smith calling all Republican city and county elected officials— and the “unscrupulous” machine that controlled them—corrupt.16

“Attacking” the now unified GOP leaders—who happened to include all the local elected officials, state legislators, congressman, both of Pennsylvania’s United States senators, Treasury Secretary Mellon, and almost every top businessman in Pittsburgh—is not a path to victory.17

The machine also included Gus Greenlee, who helped deliver African American voters critical to establishment control. He was the owner of several establishments that anchored the Hill Street district. Greenlee—Republican treasurer in the predominantly black Third Ward for Judge Charles Kline’s machine organization—began running a “numbers” operation the year after the election.18 His earnings led to his purchase of a local black baseball team and building it into one of baseball’s all-time great teams, the Pittsburgh Crawfords.

Machine opponent and Wagner political teammate Smith explained their goals to a small gathering of non-partisans: “Our quarrel is not with the Republican Party itself, but with the unscrupulous political machine that has been operating in the city and in the county for years under the cloak of that party. What right have those machine candidates, these political harmony tools, to ask for the support of the good people of this city?” He then proceeded to rip his mayoral opponent, Kline.19

The speech by Wagner was much shorter than the others made that evening but his opening says everything one needs to know about his campaign, his goals, and why he lost: “I am a candidate on the Non-Partisan ticket for the office of sheriff of Allegheny County to aid in the fight against corrupt machine politics now rampant in the administration of city and county offices.” He went on with somewhat less of a fiery challenge: “I believe that we need strict enforcement of all laws because they are laws, regardless of politics or party, and to this purpose I pledge myself and influence if I am elected.”20

I don’t think it is accurate to say that Honus Wagner lost because he didn’t campaign. Smith lost to Kline 70,680 to 19,838 in the Republican primary and then, running on the Labor ticket in the fall, lost again, 69,831 to 15,210. The Democrat candidate had 5,342 votes. (The Democrats weren’t very relevant at the time in Pennsylvania.) Wagner lost primarily because he was part of a political slate that took on the entire power structure of Pittsburgh. And was crushed. Twice in one year.21

Pittsburgh Mayor Kline ran for reelection in 1929 and won, this time with Wagner pulling out of the race after again filing for sheriff. Somebody must have warned him not to get pounded again, or more simply: “We have a slate of candidates. You are not on it.” But corruption usually catches up with politicians. Mayor Kline was arrested and convicted, resigned, and appeared to be headed to jail, but he died first. History did prove that Wagner was right about the corruption. Winning isn’t everything.22

It is also worth noting that the politicians who had been convinced of his easy victory early on (and the newspaper writers) seemed little concerned as to whether Wagner was qualified to be sheriff. The bosses figured they would choose his deputy and have someone else run the office, with Wagner as the “front man.” Wagner biographer Arthur Hittner writes that Wagner had been approached “by William H. Coleman, later a congressman, to run for sheriff of Allegheny County but Wagner had (originally) declined.” Wagner later quipped that he had told Coleman that “I knew more about hanging up base hits than murderers.”23 When Wagner finally did run, apparently his interest in being sheriff, and in listening to the pipe dreams of politicians who hoped to utilize his fame for their own purposes, overwhelmed his own honesty.

At the state and national level, the tax deal played out this way: The Coolidge-Mellon tax bill passed but, while Philly boss Vare defeated Governor Pinchot and the incumbent senator in the May 1926 primary, the Senate refused to seat Vare because of his corrupt practices in Philadelphia. The incumbent senator thus retained the seat. That incumbent was Senator George Wharton Pepper, who had been baseball’s counsel in the antitrust lawsuit of the Federal League in 1915, which resulted in the so-called antitrust exemption that still provides a protective shield to Major League Baseball today.24

MARK SOUDER served as the US Congressman for northeastern Indiana from 1995–2010. He was a senior staff member in the US House and Senate for a decade prior to being elected to Congress. He was one of the primary questioners in the hearings on steroids abuse in baseball. He has contributed articles to the last two issues of “The National Pastime,” as well as several recent SABR book projects including “Boston’s First Nine,” “Puerto Rico and Baseball,” and “From Spring Training to Screen Test.” Souder is retired other than occasional political commentary and meddling. He lives in Fort Wayne with his wife Diane and his books.

Notes

1 Arthur D. Hittner, Honus Wagner: Life of Baseball’s Flying Dutchman (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003). 244.

2 “Wagner Files His Papers for Nomination as Sheriff of Allegheny County,” Miami (FL) News, August 20, 1925.

3 “Honus Wagner for Sheriff: Famous Pirate Is Logical Candidate of Pittsburg Republicans,” New York Sun, March 25, 1917. Pittsburgh had lost its final “h” in an 1891 ruling by the US Board on Geographic Names but voted to restore it in 1911. Publications around the country were slow to adapt to the change.

4 “Groom Honus Wagner for Job as Sheriff of Allegheny County,” Binghamton (NY) Press, March 31, 1917.

5 Robert S. McElvaine, “I’m a Depression historian. The GOP tax bill is straight out of 1929,” Washington Post, November 30, 2017.

6 “County W.C.T.C. Selects Ticket,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, September 10, 1925.

7 Jan Finkel, “Honus Wagner,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/30b27632.

8 Hittner, Honus Wagner; Dennis DeValeria and Jeanne Burke DeValeria, Honus Wagner: A Biography, (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1995); William R. Cobb, ed., Honus Wagner: On His Life & Baseball (Ann Arbor: Sports Media Group, 2006). These three biographies of Wagner served as background sources. Most key facts are repeated in all of them, and this section incorporates them into the flow of the narrative.

9 Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Deacon and the Schoolmaster: Phillippe and Leever, Pittsburgh’s Great Turn-of-the-Century Pitchers (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011). 253.

10 Hittner, Honus Wagner, 213.

11 Samuel J. Astorino, “The Contested Senate Election of William Scott Vare,” Pennsylvania History, 28, no. 2 (April 1961): 187-201, https://journals.psu.edu/phj/article/view/22800.

12 David Cannadine, Mellon: An American Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 294-295.

13 “U.S. Cherishes No Purpose Save to Merit Favor of God—Coolidge,” Sioux Falls Argus-Leader, March 3, 1925.

14 Astorino, “Contested Senate Election”; John B. Townley, “Pittsburgh Has Had Three Democratic Mayors in 50 Years, Success is Story of Deals Within G.O.P., Ranks of ‘Machine’ Domination and of Political Giants Who Ruled from Behind the Scenes,” Pittsburgh Press, June 23, 1934.

15 Townley, “Pittsburgh Has Had Three Democratic Mayors”; Bruce M. Stave, The New Deal and the Last Hurrah: Pittsburgh Machine Politics (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1970), 28.

16 “Smith Assails Lawlessness and High Taxes,” Pittsburgh Press, October 20, 1925.

17 “Wagner Speaks,” Pittsburgh Press, October 20, 1925.

18 “Kline Forces,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 31, 1929.

19 “Wagner Speaks.”

20 “Wagner Speaks.”

21 “Election in Pennsylvania,” Lebanon Semi-Weekly News, September 17, 1925.

22 Stave, “The New Deal,” 30.

23 Hittner, Honus Wagner, 244.

24 “Chronology of the Year—1926,” Edw. Webster, Trenton (IL) Sun, December 30, 1926.