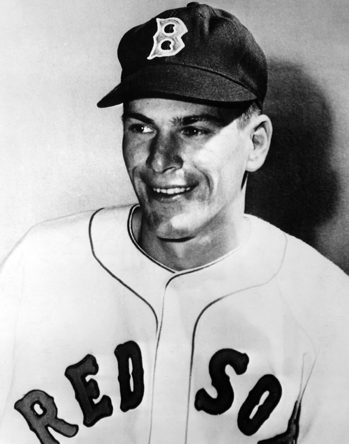

Billy Goodman

The late 1940s Boston Red Sox consisted of larger-than-life, highly paid, talented baseball men who could accomplish just about anything “except win pennants,” according to Al Hirshberg in a 1951 Saturday Evening Post article on Billy Goodman. Goodman had made his major-league debut in the spring of 1947 and was “not a glamorous slugger, not a colorful, flamboyant personality, not a magnet for autograph hounds.” In fact, he was “built like an undernourished ribbon clerk. …. Billy Goodman neither looks nor acts like a baseball star. He just goes out every day and plays the game.”1

The late 1940s Boston Red Sox consisted of larger-than-life, highly paid, talented baseball men who could accomplish just about anything “except win pennants,” according to Al Hirshberg in a 1951 Saturday Evening Post article on Billy Goodman. Goodman had made his major-league debut in the spring of 1947 and was “not a glamorous slugger, not a colorful, flamboyant personality, not a magnet for autograph hounds.” In fact, he was “built like an undernourished ribbon clerk. …. Billy Goodman neither looks nor acts like a baseball star. He just goes out every day and plays the game.”1

He played the game for 16 major-league seasons with the Red Sox, Baltimore Orioles, Chicago White Sox, and Houston Colt 45s. He finished his major-league playing career with a lifetime .300 batting average.

Goodman is remembered for being extraordinarily versatile, a trait that originated from his very early years; being the youngest and smallest in the neighborhood, “playing regularly” was his goal, which usually meant playing wherever and whenever he was asked to. Billy played every position on his Concord, North Carolina, high-school team. During his senior year he was part of a so-called “reversible battery” with a teammate, pitching one day and catching the next. Earl Kelly, sports editor of the Concord Tribune, told Hirshberg that the right-handed-throwing Goodman once pitched a game left-handed and did very well. He was always a left-handed batter.

Hall of Famer Eddie Collins, the Red Sox’ general manager in 1947, compared Goodman to Jimmy Dykes, who was considered one of the most versatile players of the 1930s. Collins, a tough critic and perfectionist, described Dykes as “the best until the kid [Goodman] came along.”

William Dale “Billy” Goodman was a native of Concord, born on March 22, 1926, the second of three sons born to Fred and Margie (DeLette Barringer) Goodman. As a major leaguer, he was listed as 5-feet-11 and 165 pounds, but during the season often fell below 150 pounds. Billy’s father was a prosperous dairy farmer, owning more than 300 acres of pastureland, which Billy worked often during his youth. The Goodman roots ran deep there, with an uncle owning comparable farmland nearby, and Billy’s grandfather, C.J. Goodman, owning the original family farmstead farther up the street. A few hundred yards from the Goodman homestead was the home of the Littles, who owned a coal and oil business in Concord. Billy and Margaret Little,2 a childhood sweetheart, were married in October 1947.

Goodman, who was simply known as Bill until he entered major-league baseball, was a three-sport star for Winecoff High School in Concord.3 He was the high scorer and captain of the high-school basketball team his junior and senior years, and he was a triple-threat halfback star on the football team. But baseball was his real love and his goal was to play professionally. Although Goodman was voted the best all-around athlete at Winecoff High, he was not remembered as a particularly outstanding baseball man. He did not hit for power, even then. Sports editor Kelly, a three-sport star athlete himself, once described Goodman as “steady and dangerous, but … never spectacular.”4 He did the little things, consistently and essentially, when his team needed a key hit and runs to stay in the game. It was just assumed that he would come through for them, and he usually did.

When the North Carolina State League (Class D) suspended its operations in World War II, the semipro four-team Carolina Victory League was formed. After high school in the summer of 1943, Billy joined the Concord Weavers, and helped win the championship that year. Billy played some outfield and was the star second baseman. The manager of the club, former minor-league star Herman “Ginger” Watts, invited young Goodman – who was 17 – to play with them. Hirshberg described the league as being “well covered by the professional scouts.”

Claude Dietrich, a scout for the Atlanta Crackers of the Double-A Southern Association, spent the summer of 1943 signing up many of Watts’s charges for the Crackers. Dietrich was admonished by Watts for missing the best player on the team, Goodman. It wasn’t the first time Goodman was overlooked, and it wouldn’t be the last. Larry Woodall, a former coach and later a scout for the Red Sox, observed, “Goodman can make a monkey out of a scout. He doesn’t look as if he can do anything right when you first see him. You have to watch him for a while before you realize that he can’t do anything wrong.”5

Dietrich signed Goodman to a Crackers contract in December 1943 for $1,200.6 He joined the Atlanta team in April 1944, playing for manager Kiki Cuyler. Goodman was listed on the roster as an outfielder though he had been mostly a second baseman for the Concord team. Billy made a good start in professional ball, making the league’s All-Star team and batting .336 in 137 games, with a league-leading 122 runs scored.

Goodman entered the Navy at the end of the 1944 season and spent his time in the South Pacific, notably the Ulithi Group of the Western Carolines and Guam. He was discharged in June 1946, and promptly went to Atlanta to see if he still had a job with the Crackers. Billy re-signed and “went to work” the very next day. Cuyler was still managing and gave Goodman the first-base job.

After a week’s trial at first base – where he got a base hit his first time at bat, then failed to hit his next 22 times – Goodman was shifted to the outfield and went on a tear, finishing the season batting .389 in 86 games. The Crackers won the Southern Association pennant and the playoff championship against New Orleans and Memphis, winning both seven-game series four games to three. Atlanta played Dallas of the Texas League in the Dixie Series – resumed after a three-year lapse – and lost four straight. Goodman went 28-for-67 in 18 playoff games (.418).

This performance was convincing enough for the Red Sox to purchase Goodman’s contract from the Crackers on February 7, 1947, for $75,000, thought to be the highest amount ever paid for a Southern Association player up to then. Goodman learned of the deal through an Atlanta Journal photographer who wanted to take pictures of him for the paper. Billy reported to Red Sox manager Joe Cronin at Sarasota, Florida, in March 1947 for spring training. The Red Sox had a championship team returning for the 1947 season, so little regard was given Goodman that spring. Billy’s first look at major-league pitching was in a Red Sox intrasquad game against Boo Ferriss, who had finished 25-6 the previous season. In his first time at bat, as Boston Globe reporter Roger Birtwell described it in an April 2, 1947, article in The Sporting News, Goodman reached for an outside pitch by Ferriss and with “the ease of a grocer’s clerk reaching for a package of biscuits, ripped a line double to left.” Interviewed at his Cleveland, Mississippi, home in July 2007, Ferriss exclaimed about Goodman: “Oh, he could hit. You know [he was] a wiry guy, wasn’t very big, not a long-ball hitter. He hit very few home runs, but he could swing a bat. And he was versatile. He was playing when I was coaching. I was very close to Billy.… He was like [Johnny] Pesky. He could spray that ball. He could hit.… You looked up and he was on base.”

When the 1947 season opened, Goodman was on the bench. He played in just 12 games with two hits – both singles – in 11 at-bats before being optioned in June to the Red Sox’ Triple-A Louisville farm club. Goodman started in the outfield for the Colonels, but took over at shortstop on July 15. He hit .340 for the year and finished among the top five American Association hitters. It was at Louisville that Goodman began playing several different positions as team needs arose. As he put it to J.G. Taylor Spink of The Sporting News, “Mr. Spink, I used up my paychecks buying myself new gloves for the various positions to which I was shifted.”7

Goodman’s successful season at Louisville brought him back to Sarasota for spring training in 1948, with a new Red Sox manager in place of Cronin. Longtime New York Yankees manager Joe McCarthy had come out of retirement to join the Red Sox for 1948 and faced the dilemma of where to play the versatile Goodman. When the 1948 season opened, Billy was once again perched on the bench.

He saw little action at the start, except for occasional fill-in work for Bobby Doerr and Johnny Pesky at second and third. When the Red Sox spiraled into a nosedive on their first Western trip – winning only one of their first seven games – McCarthy had Goodman take over at first base for the slumping Jake Jones. Billy started at first base against St. Louis on May 25, and remained there for the rest of the season, batting a solid .310 with a .414 on-base percentage and a .993 fielding average (eight errors). He was declared the club’s Rookie of the Year by the Boston baseball writers. In the playoff game to decide the league pennant against the Indians, Goodman finished 0-for-3 with a walk.

In spite of Goodman’s exceptional rookie year, McCarthy made slugging rookie Walt Dropo the starting first baseman in 1949, and Goodman was riding the bench again. When Dropo slumped to start the season, Goodman again got his job back, and the Red Sox began to improve.

Though the club lost the pennant on the season’s final day to the Yankees, Goodman had another good season, batting .298, but missed several games in August because of a fungus condition he had contracted with the Navy that weakened and blistered his hands and legs.8 Goodman received strong fan support in the All-Star voting, placing second to first baseman Eddie Robinson of the Washington Senators. He substituted for Robinson at first base in the eighth inning of the July 12 game, but he did not have an at-bat.

Based on his solid performance, Billy finally had first base locked up going into the 1950 season. But fate once again struck; in the April 30 game with the Philadelphia Athletics, Goodman sustained a chip fracture to his ankle in a collision with Ferris Fain. He was batting .333 at the time. Walt Dropo was called up from Louisville and performed phenomenally, crushing home runs at a steady pace and hitting for average. Dropo led the league with 144 RBIs and won American League Rookie of the Year honors. Goodman returned after a few weeks but had lost his first-base job.

Goodman’s strength – and resiliency – was his ability to play almost anywhere defensively, infield or outfield, which enabled him to be in the lineup more often than was expected of him. When Boston players went down with injuries, Goodman was there to spell them, and he performed well most of the time. On May 24 he began substituting for injured second baseman Bobby Doerr. He played so well there that he remained in the lineup for a while after Doerr had recovered.

When third baseman Johnny Pesky went down, Goodman filled in so admirably that there was speculation that Pesky had lost his job. By mid-June Billy had already played all four infield positions, going counter-clockwise around the diamond as each regular dropped out because of injury.9 When Pesky returned Goodman went back to his “sub” role as a one-man bench.

On July 11 Red Sox slugger Ted Williams fractured his elbow in the All-Star Game. New Red Sox manager Steve O’Neill first tried Clyde Vollmer in left field, but turned to Goodman on July 16. He had a sensational run and appeared to be made for the left-field job. In one stretch of eight games he was 17-for-32, a .531 pace, and was playing left field “as if to the manner born,” wrote Shirley Povich of the Washington Post, on July 28, 1950. On August 15 Dropo was beaned by the A’s Hank Wyse, knocking him out of the lineup. Goodman took over at first with Vollmer going to left. Dropo did not return to first base until the 23rd, and Goodman – who was batting .361 – returned to left field.

Remarkably, Goodman was the league’s leading hitter and naturally people began to wonder what to do with him when Williams returned. The rest of the team was hitting well and the Sox were on a roll, winning 44 of 61 games during Ted’s absence from the regular lineup, their .721 clip moving them two games behind the league-leading Yankees. There was reportedly some resentment among the players, knowing that temperamental slugger Williams would displace their best-hitting handyman.

But Johnny Pesky came to Goodman’s rescue. He went to manager O’Neill a few weeks before Williams’ return and offered to sit down in order to keep Goodman in the lineup. It was a selfless gesture, and one that paid off for Goodman. Not only was Billy playing exceptional ball, but he would not obtain the requisite number of at-bats to win a batting title if he did not play regularly for the balance of the season. Goodman went to third base on September 15, replacing Pesky. He went on to win the American League batting title with a .354 average. He is recognized as the only major-league player ever to win a batting title without having a regular position. The Red Sox finished third, four games behind the first-place Yankees.

For his heroics on the diamond, Goodman was recognized as a candidate for the 1950 top male Athlete of the Year by the Associated Press. He finished 11th in the voting – Jim Konstanty of the Philadelphia Phillies won the award – among many sports notables of the day, amateur and professional. Goodman also finished second in the league MVP voting to New York shortstop Phil Rizzuto.

Astonishingly, over the winter there was talk that there might not be everyday room in the lineup for the 1950 batting champion. Manager O’Neill characterized Goodman as a bit of a pleasant dilemma. The Boston press labeled it the “Goodman problem.” O’Neill rationalized that Goodman should play every day; yet, when asked what he would do with his other stars, and whom he would sit down, O’Neill countered that Goodman would be his “number one utility man while still playing regularly every day.”10 Only days later, the Red Sox traded right fielder Al Zarilla, a .325 hitter in 1950, to the White Sox. O’Neill confided that this was done to provide steady work for Goodman in the lineup. True to his word, O’Neill started the season with Goodman as a regular in the outfield, batting second.

The Red Sox got off to a bad start, losing their first three games. O’Neill showed no patience and quickly began to juggle his lineup, including sitting down Walt Dropo, who was not hitting, and moving Goodman to first base. Billy again moved between three infield positions – first, second, and third – and some outfield. He received ample playing time in ’51, but did not reach the heights of 1950, finishing the season batting .297. The Red Sox finished in third place, 11 games behind the first-place Yankees.

The year 1952 was as a period of change for the Red Sox, with a new manager, core players either leaving or aging, and vacancies needing replacements. Bobby Doerr called it quits at the age of 33 toward the end of the 1951 season, and manager Steve O’Neill was replaced by Lou Boudreau in the offseason. Ted Williams was recalled to military duty because of the Korean War and left the team on May 2. Both Pesky and Dropo were traded away in midseason. There were holes to fill.

The foremost dilemma for Boudreau – “the game’s greatest manipulator,” wrote Shirley Povich of the Washington Post – was whom to call on to replace future Hall of Famer Bobby Doerr.11 Boudreau juggled his lineup with regularity throughout the year, favoring youth over experience, speed and defense over power, and constant platooning. Goodman played three infield positions – mostly at second base – and some outfield. Billy had more at-bats (513) than any other Red Sox player, and was second on the club with a .306 batting average. The Red Sox had little to cheer about, however, finishing in sixth place, 19 games out of first.

The next season, 1953, was not looking to be a much better year for the Red Sox, but it was a happy one for Billy Goodman because Boudreau made him his full-time second baseman. This was the first time in the major leagues that Billy could call a position his own, and he was doubly pleased because he was taking over from his idol, Bobby Doerr.

Interviewed at his Oregon home years later, Bobby Doerr described Goodman warmly: “He [was] just a very, very fine person and a darn good ballplayer. He was like the perfect guy to be on a ballclub because he could play so many different positions. If he was [playing] utility he was great when he went in [to a game]. … He played a good first base. He didn’t have the power that first basemen generally have, but he was always on base and ran the bases good. [He was a] good fielder. … As a utility player he was perfect in that way, too. He could go in any time and do a good job.”12

On May 10, 1953, Billy got into a dispute with an umpire over a close call, and became so enraged that he had to be restrained by teammate Jimmy Piersall, who wrapped his arms around the flailing second sacker and bodily carried him from the field. Goodman sustained cartilage damage to his ribs from the “hugging” incident, and was sidelined for nearly a month. Boudreau later remarked that Goodman’s absence was a factor in the Red Sox not being a contender in 1953. Casey Stengel agreed, commenting that Goodman’s absence “changed the whole complexion of the first division.”13 Boston finished in fourth place, 16 games behind the first-place Yankees. In spite of his injury and long absence, Goodman had a good year, batting .313, tied for third with Minnie Minoso in the American League batting race. He was named to the AL All-Star team as the starting second baseman. He went 0-for-2 with a walk, and was caught stealing.

Goodman played on mediocre Red Sox teams from 1954 to 1956. They finished fourth each year. He continued his steady play, batting .303, .294, and .293, respectively, while often being used in utility roles. In 1957 he was being used sparingly by manager Mike Higgins, and the Red Sox traded him to the Baltimore Orioles for pitcher Mike Fornieles.

Orioles manager Paul Richards regarded Goodman as the team’s ultimate utility player, using him at all infield positions – mostly third base – as well as in right field and left field, a total of six fielding slots. Billy stroked a home run – one of 19 he hit for his entire major league career – in his debut with Baltimore, and batted .308 for the Orioles for the season. On December 3 the Orioles traded Goodman, Tito Francona, and Ray Moore to the Chicago White Sox for Larry Doby, Jim Marshall, Jack Harshman, and Russ Heman. Billy played solid baseball in 1958 for manager Al Lopez, mostly at third base, and batting .299. Chicago finished 10 games behind New York, in second place.

The “Go-Go” White Sox were the American League champions in 1959 – their first World Series since the infamous 1919 Black Sox scandal – and were known mostly for their speed, defense, and solid pitching. “Powderpuff hitters,” they were called. Goodman, who batted .250 during the regular season, platooned at third base with Bubba Phillips. The White Sox lost the World Series, four games to two, to the Los Angeles Dodgers. Goodman played in five of the six games, starting in three of them, and in pinch-hit roles. He went 3-for-13 – all singles – in the Series.

Chicago used Billy sparingly in 1960 and 1961 as a utility player and pinch-hitter. The White Sox did not equal their success of 1959, finishing third in 1960 and fourth in 1961. Goodman played in just 30 games in 1960 and 41 in ’61, hitting .234 and .255, respectively.

Almost 36 years old, Goodman went to spring training with the White Sox in 1962, but he was given his unconditional release on April 3. On May 15, he signed with the expansion Houston Colt .45s of the National League. He played in utility roles once more, appearing in 82 games and batting .255. He was released after the season.

For 1963 Goodman signed on as player-manager of the Durham Bulls of the Class-A Carolina League. He left that assignment toward the end of the 1964 minor-league season, going to Houston’s rookie camp in Cocoa, Florida, as manager-instructor, where he remained through ’65. In the winter of 1966 Billy caught on with his old team, the Red Sox, who hired him as a “special scout.” In 1967 he joined the Kansas City Athletics as an instructor, and then spent four years with the Braves in a similar role.

In 1973 Goodman joined the Kansas City Royals at their Baseball Academy in Sarasota, Florida (by then Goodman’s home town), as an infield and hitting instructor. The Royals closed their academy in the spring of 1974, but retained Goodman on the payroll along with a few other instructors. Billy stayed on as manager of one of their rookie league clubs in the Gulf Coast League, the Academy Royals. In May 1976 the Atlanta Braves hired Billy, again, this time as an instructor in their minor-league system. In June he joined the Braves’ Triple-A Richmond club as batting instructor.

Goodman’s widow, Margaret, said that between 1977 and 1982 Billy was retired from baseball, playing golf, fishing, hunting, and gardening, and doing some occasional work with her in her antiques business – her store was called the Babe Ruth Auxiliary — and in their other commercial properties. He appeared for an old-timers game, the Cracker Jack Old-Timers Baseball Classic, in July 1982 at RFK Stadium in Washington. Billy and Margaret also owned a 30-acre orange grove which they sold before he died.

Billy became ill with multiple myeloma in 1983, and died on October 1, 1984, in Sarasota. He was 58. He was survived by Margaret, of Sarasota; daughter Kathy Goodman Simpkins of Concord, North Carolina; and son Robert Goodman – named after Goodman’s good friend, Bobby Doerr – of Bradenton, Florida. By 2007 Margaret had three grandchildren – all girls – ages 24, 17, and 16. Asked if she ever remarried, Margaret’s response was a decided “Oh no. We grew up together and there’s one love in a lifetime, and I had him.”14

Billy Goodman played in 1,623 games in his major-league career, collecting 1,691 base hits and a .300 lifetime batting average. He played in two All-Star Games and one World Series. He ranks 10th all-time for on-base percentage in a season by a rookie, with a .414 percentage in 1948. In 1969, Goodman was honored by his native state, North Carolina, by being inducted into its Sports Hall of Fame. He is also a member of the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame, inducted in 2004.

Last revised: May 8, 2023 (zp)

An earlier version of this biography originally appeared in SABR’s “Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948” (Rounder Books, 2008), edited by Bill Nowlin. It also appeared in SABR’s “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda, and “Red Sox Baseball in the Days of Ike and Elvis: The Red Sox of the 1950s” (SABR, 2012), edited by Mark Armour and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Thanks to Dick Bresciani, Boston Red Sox vice president of publications and archives.

Hirshberg, Al. Saturday Evening Post, March 17, 1951, 34, 141-144.

Spatz, Lyle, ed. The SABR Baseball List & Record Book (New York: Scribner, 2007), 349.

Notes

1 Al Hirshberg, “That Modest Young Guy in the Outfield,” Saturday Evening Post, March 17, 1951.

2 Ibid.; J.G. Taylor Spink, “Goodman Proves Right Man at First Base,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1948. Goodman’s wife, Margaret, was known as “Evelyn” – she was born Margaret Evelyn Little – throughout her youth and during Billy’s early years in baseball. Billy said in his 1948 interview with J.G. Taylor Spink, “My wife was Evelyn Little.” According to Margaret – in interviews in May, September, and October 2007 – her first name took hold when they moved to Sarasota, Florida, and started their businesses there. She used the given name, Margaret, on all formal documents, and it stuck.

3 Hirshberg. Billy Goodman was called “just plain Bill” in Concord, where he played high school and semipro ball, as well as with the Atlanta Crackers. According to Goodman’s widow, Margaret, the name Billy took hold while he was with the Red Sox, but she does not remember how it got started.

4 Hirshberg.

5 Hirshberg.

6 Jack Troy, “Goodman, Expert Cook, Gives Hot Plate Service to Crackers,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1944. Atlanta scout Claude Dietrich tells the tale of the first time he encountered Goodman “wearing an apron” cooking a rabbit in the Goodman home. Dietrich was startled by Billy’s slight appearance, accentuated by his donning of an apron. Father Fred Goodman later explained that Billy took over the kitchen duties as “chief cook” after his mother’s death that year.

7 Spink.

8 Roger Birtwell, “Whattaman Goodman – and What a Man!” The Sporting News, September 13, 1950. Goodman was plagued with a chronic fungus – a so-called “saltsea fungus called ‘jungle-rot’,” the Birtwell article says. It made him generally weak, and “affected his hands so much he couldn’t get a firm grip on his bat.” Margaret Goodman recalled the circumstances, saying that Billy “had to wear special things on his feet and he had something on his hands when he batted.… It was always with him.”

9 Birtwell, 3, 6; Bill Nowlin, Mr. Red Sox: The Johnny Pesky Story (Rounder Books, 2004), 136-138. Goodman briefly filled in for Vern Stephens at shortstop “on one occasion” before he subbed for Pesky, thus effectively playing at every infield position, moving counter-clockwise around the infield.

10 Steve O’Leary, “Goodman Problem Tackled by O’Neill – He’ll Be a ‘Daily Sub’,” The Sporting News, November 29, 1950.

11 Shirley Povich, “This Morning, with Shirley Povich,” Washington Post, April 17, 1952.

12 Bobby Doerr, telephone interview, June 5, 2007.

13 Hy Hurwitz, “Boudreau Bubbles Over Bosox Babes – and His New Pact,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1953.

14 Margaret Goodman, telephone interviews, May, September, and October 2007; Doerr. Goodman’s widow, Margaret, was not entirely certain about the years 1977 and 1982. She did feel that Billy was most likely fully retired at the time and engaged in recreational pursuits along with his occasional assistance in her antiques business. Doerr – who maintained some contact with Goodman – expressed a similar opinion.

Full Name

William Dale Goodman

Born

March 22, 1926 at Concord, NC (USA)

Died

October 1, 1984 at Sarasota, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.